Biodiversity in Wallonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROCHEFORT, V1

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 644000 646000 648000 650000 652000 654000 656000 658000 660000 ! ! ! ! 5°1'0"E !5°2'0"E 5°3'0"E 5°4'0"E 5°5'0"E 5°6'0"E 5°7'0"E 5°8'0"E 5°9'0"E 5°10'0"E ! 5°11'0"E 5°12'0"E 5°13'0"E 5°14'0"E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! N " ! ! GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR518 0 ! ' ! 3 ! 1 ! ! ° ! ! Int. Charter Act. ID: N/A Product N.: 02ROCHEFORT, v1 0 5 ! ! ! F R ! ! ! o ! u ! n ! i ! s ! i ! d Dén s ! ! Rochefort - BELGIUM d ! e ! ! ! ! e a ! ! ! u ! ! ! R ! ! e d ! ! ! 0 ! 0 Flood - Situation as of 17/07/2021 u u ! ! ! ! 0 0 ! x ! 0 ! 0 ! ! ! Lavis ! ! 4 4 ! ! 6 ! 6 ! ! ! ! ! Delineation MONIT01 - Detail map 02 5 ! ! 5 5 ! 5 ! R ! ! ! ! u ! ! d is Noord-Brabant ! ! e se ! Marche-en-Famenne Arnsberg D! a ! ! o u ! Limburg Dusseldorf ! ! Custinne nn ! Prov. ! ! e ! u ! (NL) ! x ! Antwerpen ! ! ! e ! ! n ! N L ig ! " Prov. 'Iwoigne 0 ! ! o ! ' ! w 2 1 ! Y Navaugle! ° Limburg l' ! 0 H! umain 5 ! R Prov. ! u Netherlands l ! a (BE) ! i ! Vlaams-Brabant ! s M ! s ! L ! North Sea 'Ywo e igne o Havrenne ! r a Koln s N u ! ! " ! Prov. 01 a R 0 ! Belgium ' y d ! 2 Brabant h e e 1 ! ! i ! ° ! ! n 0 Wallon x ! e Germany 5 n ! , ! u a ! ! r ^ W a i ! h B Brussels a ! a ! c ! e se l ! u a u L Me Prov. Liege ! V sea uis ! ! e R s ! L ge , Lahn ! s Lo Prov. -

ZONE DE POLICE DE GAUME Chiny, Etalle, Florenville, Meix-Devant-Virton, Rouvroy, Tintigny, Virton

Confidentiel Respect, Solidarité, Esprit de service ZONE DE POLICE DE GAUME Chiny, Etalle, Florenville, Meix-devant-Virton, Rouvroy, Tintigny, Virton FORMULAIRE DE DEMANDE DE SURVEILLANCE HABITATION EN CAS D’ABSENCE La surveillance des habitations est un service totalement gratuit, offert par la Zone de Police de Gaume. Chaque citoyen résidant sur ce territoire, a le droit d’en faire la demande. Bien que toute information sur votre absence nous soit utile en termes de prévention, nous ne garantissons pas une surveillance en dessous d’une absence de 5 jours et au-delà d’un mois. Nom : Prénom : Date de naissance : Adresse : Code Postal : Localité : Téléphone / GSM : Adresse mail : Type d’habitation : Autres endroits à surveiller (Magasin, hangar, atelier, abri de jardin…) : Date et heure de départ : vers heures Date et heure de retour : vers heures Possibilité de contact (adresse de votre destination et/ou numéro de téléphone) : Personne de contact (Nom et prénom) : Adresse : Code Postal : Localité : Téléphone : Dispose des clefs de la maison : OUI NON Dispose du code alarme : OUI NON Véhicule(s) dans le garage ou devant la maison : Description(s) : Installation d’un système d’alarme : OUI NON Modèle : Installateur : Minuterie à l’intérieur de l’habitation (déclenchant un éclairage) : OUI NON programmée à : Eclairage de sécurité ou éclairage dissuasif à l’extérieur : OUI NON Chien de garde ou autres animaux : OUI NON Caractéristiques : Je souhaite le passage à mon domicile du conseiller en prévention vol de la zone de Police : OUI NON Autres mesures de prévention ou de sécurité (gardes privés, objets de valeur enregistrés, coffres forts préalablement vidés, serrure supplémentaire à la porte extérieure, personne (voisin) pour tondre la pelouse ou relever le courrier ou soigner les animaux) : 1 DECLARATION DU DEMANDEUR Par ce formulaire, je souhaite obtenir une surveillance policière de mon habitation durant la période indiquée. -

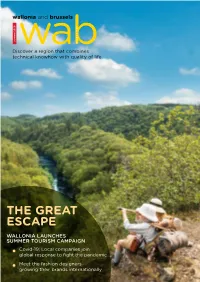

Wabmagazine Discover a Region That Combines Technical Knowhow with Quality of Life

wallonia and brussels summer 2020 wabmagazine Discover a region that combines technical knowhow with quality of life THE GREAT ESCAPE WALLONIA LAUNCHES SUMMER TOURISM CAMPAIGN Covid-19: Local companies join global response to fight the pandemic Meet the fashion designers growing their brands internationally .CONTENTS 6 Editorial The unprecedented challenge of Covid-19 drew a sharp Wallonia and Brussels - Contact response from key sectors across Wallonia. As companies as well as individuals took action to confront the crisis, www.wallonia.be their actions were pivotal for their economic survival as www.wbi.be well as the safety of their employees. For audio-visual en- terprise KeyWall, the combination of high-tech expertise and creativity proved critical. Managing director Thibault Baras (pictured, above) tells us how, with global activities curtailed, new opportunities emerged to ensure the com- pany continues to thrive. Investment, innovation and job creation have been crucial in the mobilisation of the region’s biotech, pharmaceutical and medical fields. Our focus article on page 14 outlines their pursuit of urgent research and development projects, from diagnosis and vaccine research to personal protec- tion equipment and data science. Experts from a variety of fields are united in meeting the challenge. Underpinned by financial and technical support from public authori- ties, local companies are joining the international fight to Editor Sarah Crew better understand and address the global pandemic. We Deputy editor Sally Tipper look forward to following their ground-breaking journey Reporters Andy Furniere, Tomáš Miklica, Saffina Rana, Sarah Schug towards safeguarding public health. Art director Liesbet Jacobs Managing director Hans De Loore Don’t forget to download the WAB AWEX/WBI and Ackroyd Publications magazine app, available for Android Pascale Delcomminette – AWEX/WBI and iOS. -

Vous Désirez En Savoir Plus Sur L'épi ? Liste Des Prestataires

VOUS DÉSIREZ EN SAVOIR PLUS SUR L'ÉPI ? LISTE DES PRESTATAIRES & COMPTOIRS DE CHANGE www.enepisdubonsens.org VOUS Y TROUVEREZ : AUTOUR D'ARLON et AUBANGE ✔ La possibilité de devenir membre de l'Épi Lorrain en ligne. Les comptoirs de change ✔ Le projet de l'Épi expliqué et ses actualités. ✔ L'annuaire des prestataires de l'Épi sur une carte interactive, avec un ARLON DU TIERS ET DU QUART, 153 rue de Neufchâteau classement par catégorie et la possibilité de télécharger cette liste mise à jour ARLON EPICES & TOUT, 103 rue des faubourgs régulièrement. ARLON (Toernich) COMPTOIR DE LA CIGOGNE, 30 rue haute ✔ Des informations complémentaires pertinentes et alternatives sur les monnaies, l'économie, la finance, l'argent,... Les prestataires ✔ L'agenda de l'Épi. Les Bacchanales (café culturel) 37 Grand place, Arlon BENTZ Bougies & Pompes Funèbres 13 rue du Marché au Beurre, Arlon Ferme les Bleuets (oeufs) 101 rue Welschen, Longeau BIO-Lorraine (légumes bio) 17 Fahrengrund, Viville L'ÉPI LORRAIN ASBL Brasserie d'Arlon (brasserie artisanale) 57 rue Godefroid Kurth, Arlon 27, RUE DE VIRTON Le Comptoir de la Cigogne (épicerie fine) 30 rue Haute, Toernich 6769 MEIX-DEVANT-VIRTON Créativlabels (stickers vitrines et murs) 5 rue de la scierie, Frassem Dijest Finger food truck Itinérant sur Arlon et environs Tél : 0473/ 422 330 Envie d'apprendre (coach scolaire) 39 Rue du Maitrank, Bonnert E-mail : [email protected] Ecobati (matériaux de construction écologique) 119 rue de la Semois, Arlon Site web : www.enepisdubonsens.org Épices & tout (épicerie -

Cerfontaine : Cerfontaine Tité De Cerfontaine (Voir Encadré)

Ouvertures et châssis Protection de l’habitat traditionnel Dans le bâti traditionnel de l’entité de Cer- Afin de préserver au mieux le caractère de fontaine, les ouvertures de forme verticale Dispositifs de protection appliqués sont dominantes. nos villages, différentes mesures réglemen- taires spécifiques sont appliquées dans l’en- à l’entité de Cerfontaine : Cerfontaine tité de Cerfontaine (voir encadré). - la commune comporte 5 monuments et si- Certaines de ces mesures permettent d’oc- tes classés Monument Historique troyer des primes pour la rénovation et l’em- imposte - 115 biens sont repris à l’inventaire du Pa- Cerfontaine bellissement extérieur d’immeubles d’habi- trimoine Monumental de la Belgique et se tation. répartissent dans les différents villages de Daussois deux ouvrants Toutes ces mesures sont reprises dans le l’entité Senzeilles Code Wallon de l’Aménagement du Ter- Le châssis est un élément secondaire important pour le bon équilibre de ritoire, de l’Urbanisme et du Patrimoine Silenrieux la façade. Les fenêtres à imposte fixe et comportant deux ouvrants, ap- (CWATUP). Soumoy pelés généralement châssis en T, sont les plus fréquentes dans l’habitat traditionnel et les mieux adaptées. N’hésitez pas à consulter le service urba- Villers-deux-Eglises nisme de votre commune si vous désirez en savoir plus sur ces prescriptions La porte de grange est l’ouverture principale et le témoin de l’ancien- ne fonction agricole. La forme de la porte de grange peut varier selon En savoir plus la date de construction où la région où elle se trouve. Différentes brochures de découverte, de sensibilisation et de conseil en aménagement du territoire, urbanisme et patrimoine sont disponibles au sein des services et associations Linteau droit Linteau droit Cintré en retrait avec auvent en bois actives sur le territoire. -

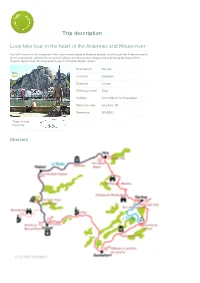

Trip Description Loop Bike Tour in the Heart of the Ardennes and Meuse

Trip description Loop bike tour in the heart of the Ardennes and Meuse river You will have so much to explore in this undisclosed region of Belgium by bike: ride through the Ardennes and its green countryside, discover the provincial folklore and picturesque villages and relax along the banks of the majestic Meuse river. What a pleasant way of living the Belgian dream! Destination Europe Location Belgique Duration 5 days Difficulty Level Easy Validity from March to November Minimum age 12 years old Reference WA0501 Type of stay loop trip Itinerary Leave your problems behind as suggests a famous Belgian proverb and be part of this fabulous bike trip in the great outdoors of both the Ardennes and along the Meuse river. Naturally you will be amazed by the renowned Belgian good mood! Your trip begins in Dinant, the city where Adolphe Sax, the inventor of the musical instrument, was born. Enjoy the most charming places of the Ardennes such as Rochefort, Marche-en-Famenne or Durbuy and cross picturesque landscapes. You ride sometimes on small countryside roads, on large cycle paths or along the Meuse river between Huy and Dinant passing by Namur, the capital of Wallonia. All the ingredients are combined in this loop bike tour to enjoy a great adventure! Eager for culture? Explore the citadels of Namur and Dinant, the castel of Modave or the fort of Huy. Keen to relax in the nature? The natural area of Leffe and Famenne regions or the peaceful banks of the Meuse river await you! Not to mention the Belgian gastronomy with its French fries, its waffles, its chocolate or all types of beers: all your senses will be awake! Day 1 Dinant - Rochefort Get onto your bike for a perfect adventure! Dinant is your starting point and you will find plenty of activities to enjoy there. -

Parc Naturel De Gaume »

18 décembre 2014 Arrêté du Gouvernement wallon portant création du « Parc naturel de Gaume » Le Gouvernement wallon, Vu le décret du 16 juillet 1985 relatif aux parcs naturels, ses articles 2, 3, 4, 5 et 6; Vu les articles D.29-1 à D.29-24, D. 49 à 61 et R. 46, 47 et 49 du Livre Ier du Code de l'Environnement; Vu la constitution d'une association de projet au sens de l'article L 1512-2 du Code de la démocratie locale et de la décentralisation pour la création du « Parc naturel de Gaume » en date du 1er août 2012, regroupant les communes d'Aubange, d'Etalle, de Florenville, de Meix-devant-Virton, de Musson, de Rouvroy, de Saint-Léger, de Tintigny et de Virton; vu que cette association de projet constitue le pouvoir organisateur du « Parc naturel de Gaume »; Vu qu'un comité d'étude a été institué le 1er août 2012 par le pouvoir organisateur; que ce comité d'étude a établi un rapport relatif à la création du parc naturel conformément à ce que prévoit l'article 3, alinéa 2 du décret du 16 juillet 1985 relatif aux parcs naturels; que ce rapport a été présenté au pouvoir organisateur le 20 décembre 2012; Vu que, sur cette base, le pouvoir organisateur a établi un projet de création de parc naturel portant sur la dénomination, les limites, le plan de gestion du parc naturel et l'inscription de tout ou partie du territoire du parc naturel dans un périmètre où s'applique le Règlement général sur les bâtisses en site rural; Vu les avis favorables des conseils communaux des communes d'Aubange, d'Etalle, de Florenville, de Meix-devant-Virton, de -

Fiche Descriptive Sur Les Zones Humides Ramsar

Fiche descriptive sur les zones humides Ramsar (FDR) Catégories approuvées dans la Recommandation 4.7modifiée par la Résolution VIII.13 de la Conférence des Parties contractantes Note aux rédacteurs: 1. La FDR doit être remplie conformément à la Note explicative et mode d’emploi pour remplir la Fiche d’information sur les zones humides Ramsar ci-jointe. Les rédacteurs sont vivement invités à lire le mode d’emploi avant de remplir la FDR. 2. La FDR remplie (et la ou les carte(s) qui l’accompagne(nt)) doit être remise au Bureau Ramsar. Les rédacteurs sont instamment priés de fournir une copie électronique (MS Word) de la FDR et, si possible, des copies numériques des cartes. 1. Nom et adresse du rédacteur de la FDR: USAGE INTERNE SEULEMENT Philippe Frankard et Pascal Ghiette J M A Centre de recherche de la Nature, des Forêts et du Bois c/o Station scientifique des Hautes-Fagnes Mont-Rigi Date d’inscription Numéro de référence du site B-4950 Robertville Belgique 2. Date à laquelle la FDR a été remplie ou mise à jour: 19 juin 2002 3. Pays: Belgique 4. Nom du site Ramsar: Les Hautes Fagnes 5. Carte du site incluse: a) copie imprimée (nécessaire pour inscription du site sur la Liste de Ramsar): oui π -ou- non π b) format numérique (électronique) (optionnel): oui π -ou- non π 6. Coordonnées géographiques (latitude/longitude): 50°32' N 06°06' E 7. Localisation générale: Province de Liège. Liège: chef-lieu de la province du même nom, 250.000 habitants. Distance Liège/Hautes-Fagnes: 40 km. -

Marche-En-Famenne N° 54/7-8

AYE MARCHE-EN-FAMENNE 54/7-8 CARTE GÉOLOGIQUE DE WALLONIE ÉCHELLE : 1/25 000 NOTICE EXPLICATIVE Plus d'infos concernant la carte géologique de Wallonie : http://geologie.wallonie.be [email protected] Un document édité par le Service public de Wallonie, Direction générale de l’Agriculture, des Ressources naturelles et de l’Environnement. Dépôt légal : D/2014/11802/76 Éditeur responsable : José Renard, Directeur général a. i., DGARNE - Avenue Prince de Liège, 15 - B-5100 Namur. Reproduction interdite. SPW | Éditions, CARTES N° vert : 0800/11 901 - Site : www.wallonie.be AYE - MARCHE-EN- FAMENNE Laurent BARCHY & Jean-Marc MARION Université de Liège Service de paléontologie animale et humaine Sart-Tilman, B 18, B-4000 Liège http://www.ulg.ac.be/paleont/ Photographie de couverture : La chapelle de Waha (1060) construite sur et avec les grès de la Formation de la Lomme. Les vitraux ont été réalisés par J.-M. Folon NOTICE EXPLICATIVE 2014 Déposée : juin 2006 Acceptée pour publication : décembre 2009 Carte Aye – Marche-en-Famenne n° 54/7-8 Résumé Située à cheval sur les provinces de Namur et de Luxembourg, la portion de territoire couverte par la carte montre des contrastes géomorphologiques importants qui permettent d’y reconnaître quatre régions géographiques : la transition Condroz-Famenne, la Famenne proprement dite, la Calestienne et le premier contrefort de l’Ardenne. Le sous-sol est constitué par des dépôts paléozoïques qui s’étagent depuis l’Emsien jusqu’au Famennien supérieur. Ces séries sédimentaires dévoniennes, divisées en formations, sont formées de roches carbonatées et siliciclastiques qui ont subi l’orogenèse varisque. -

ROCHEFORT, V1 0 ' 8 2 ° 0 5 Rochefort - BELGIUM Flood - Situation As of 17/07/2021 0 0

640000 650000 660000 670000 680000 690000 700000 5°2'0"E 5°9'0"E 5°16'0"E 5°23'0"E 5°30'0"E 5°37'0"E 5°44'0"E GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR518 N " Int. Charter Act. ID: N/A Product N.: 02ROCHEFORT, v1 0 ' 8 2 ° 0 5 Rochefort - BELGIUM Flood - Situation as of 17/07/2021 0 0 0 0 Delineation MONIT01 - Overview map 01 0 0 0 0 9 9 5 5 5 5 Noord-Brabant Arnsberg Limburg Dusseldorf Prov. (NL) Antwerpen Prov. Limburg Prov. Netherlands Vlaams-Brabant (BE) KoNolrtnh Sea Prov. 01 Belgium R Brabant h in Wallon e , Germany ^ W Brussels a e al Meus Prov. Liege m, Lahn France Oh Prov. Namur 02 Koblenz !( e l l Rochefort e Trier o s Detail 03 M , Prov. e tt 25 lo Luxembourg Sure e km s Mo N " (BE) Luxembourg 0 ' 1 2 ° 0 5 ! Durbuy 0 0 Cartographic Information 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 8 N 5 5 " 5 5 0 ' 1:90000 Full color A1, 200 dpi resolution 1 2 ° 0 5 0 2 4 8 km Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 31N map coordinate system Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ± Legend Crisis Information Hydrography Transportation Flooded Area River Highway (17/07/2021 17:32 UTC) Previous Flooded Area Stream Primary Road (15/07/2021 05:50 UTC) General Lake Secondary Road Information Land Subject to Long-distance railway Inundation Area of Interest Reservoir Tramway Detail map River Helipad Administrative Physiography, Land Use, Land boundaries Facilities Cover, Facilities area feature and Province Navigable canal Built-Up area ! ! ! ! ! ! Municipality Dam Features available in the vector package Placenames ÏÏÏ Berthing Structure 0 0 ! Placename 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 7 Consequences -

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles BELGIUM

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles BELGIUM by Alain Peeters The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. All rights reserved. FAO encourages the reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. © FAO 2010 3 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 5 Country location 5 2. SOILS AND TOPOGRAPHY 8 Topography and geology 8 Soil types 10 3. CLIMATE AND AGRO-ECOLOGICAL ZONES 11 Climate 11 Geographical regions 13 Agro-ecological regions 14 Forests 22 4. -

Late Middle to Late Frasnian Atrypida, Pentamerida, and Terebratulida

Disponible en ligne sur www.sciencedirect.com Geobios 41 (2008) 493–513 http://france.elsevier.com/direct/GEOBIO/ Original article Late Middle to Late Frasnian Atrypida, Pentamerida, and Terebratulida (Brachiopoda) from the Namur–Dinant Basin (Belgium) Atrypida, Pentamerida et Terebratulida (Brachiopoda) de la partie supe´rieure du Frasnien moyen et du Frasnien terminal du Bassin de Namur-Dinant (Belgique) Bernard Mottequin a,b a Department of Geology, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland b Paléontologie animale, université de Liège, bâtiment B18, 4000 Liège 1, Belgium Received 18 January 2007; accepted 17 October 2007 Available online 11 March 2008 Abstract In the Namur–Dinant Basin (Belgium), the last Atrypida and Pentamerida originate from the top of the Upper Palmatolepis rhenana Zone (Late Frasnian). Within this biozone, their representatives belong to the genera Costatrypa, Desquamatia (Desquamatia), Radiatrypa, Spinatrypa (Spinatrypa), Spinatrypina (Spinatrypina?), Spinatrypina (Exatrypa), Waiotrypa, Iowatrypa and Metabolipa. No representative of these orders occurs within the Palmatolepis linguiformis Zone. The disappearance of the last pentamerids, mostly confined to reefal ecosystems, is clearly related to the end of the edification of the carbonate mounds; it precedes shortly the atrypid one. This event, resulting from a transgressive episode, which induces a progressive and dramatic deterioration of the oxygenation conditions, takes place firstly in the most distal zones of the Namur– Dinant Basin (southern border of the Dinant Synclinorium; Lower P. rhenana Zone). It is only recorded within the Upper P. rhenana Zone in the Philippeville Anticlinorium, the Vesdre area, and the northern flank of the Dinant Synclinorium. It would seem that the terebratulids were absent during the Famennian in this basin, probably due to inappropriate facies.