Uncovering Everyday Learning and Teaching Within the Quilting Community of Aotearoa New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pieceful Times

Volume 84 March 2019 The Pieceful Times E y e S p y We have decided to start a fun March 2019 new game with our newsletters here at Sew Pieceful called Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat “Eye Spy!” Find the tiny, hidden 1 2 spool of thread hidden within Open the newsletter within the first Sew 1-4pm week of publication. Stop by 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sew Pieceful to let us know Itty Bitty Jelly RealTree where it is and you will be Club Roll Rug Quilt 1-4pm Class Class entered into a drawing for a fun 10-2pm 1-4pm prize. The winner will then be (Two Session drawn the following Monday! Class) 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Let’s Eat Jelly Open Medford Club Roll Rug Sew Quilt 1-4pm Class 1-4pm Show 10-2pm 10-4pm (Two Session Class) 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Need a place to sew that has Medford FW Jacqueline FW Marti RealTree Quilt Fellow- Bargello Fellow- Michell Quilt plenty of room and none of the Show ship Class ship Club Class 10-3pm 1-4pm 1-4pm 1-4pm 1-4pm 1-4pm distractions of home? Our classroom is open several 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Pack It Up Wisdom Braided Fridays in March to encourage Bag Class BOM Twist as much sewing as possible to 12-4pm 1-4 Runner Class get all those UFO’s finished! For 1-4pm FREE you are welcome to stay- 31 from 1-4pm! Space is limited, so give us a call if you plan on coming! P a g e 2 The Pieceful Times Join us for our fourth project Itty Bitty Club for the Itty Bitty Club at Sew Date: First Wednesday of the Month Pieceful! Connie is heading Wednesday, March 6th up the Itty Bitty Club for all Time: 1pm-4pm projects full of tiny pieces! Club Fee: $49.99 per year (Plus Materials) With a new project being started every other month, this club will meet from 1-4pm on the first Wednesday of every month to work on their itty bitty projects. -

Historia Patchworku Patchwork I Pikowanie (Quilting)

Historia patchworku Patchwork i pikowanie (quilting) były praktykowane od wieków, zarówno jako rzemiosło praktyczne, jak i dekoracyjne. Ich popularność utrzymywała się w zależności od zmian w społeczeństwie, a style rozwijały się w zależności od dostępnych zasobów i statusu społecznego twórcy. Dzięki swej bogatej i ciekawej historii, wiek XXI zaowocował rozkwitem tej formy rzemiosła, które stało się popularne i powszechnie praktykowane, bazując na tradycyjnych umiejętnościach i pozwalając na eksperymentowanie ze współczesnymi technikami artystycznymi. Dowody na istnienie patchworku widać na przestrzeni stuleci – istnienie większego kawałka tkaniny, składającego się z małych kawałków, połączonych w całość pikowaniem jest udokumentowne w historii. Najwcześniejsze ślady zostały zlokalizowane w egipskich grobowcach, a także we wczesnych Chinach około 5000 lat temu. Kolejne znaleziska zostały datowane już we wczesnym średniowieczu, gdzie warstwy pikowanej tkaniny zostały wykorzystane w konstrukcji zbroi - gdzie utrzymuje ciepło i chroni żołnierza. Podobna konstrukcję miały pancerze japońskie. Stosując tę technikę, patchworki zaczęły pojawiać się w gospodarstwach domowych od XI do XII wieku. Ponieważ europejski klimat mocno się ochłodził w tym czasie, potrzeba używania ciepłych nakryć wzrosła i tak rozwinęla się praktyka upiększania prostej tkaniny poprzez stworzenie wzoru i projektu dekoracyjnego pikowania. Najstarszy istniejący użytkowy quilt to pikowany dywan, znaleziony w mongolskiej jaskini. Jest przechowywany w Sankt Petersburgu, powstał prawdopodobnie w XI wieku. Tristana i Izoldy. Tristan Quilt powstał na Sycylii ok. 1360 roku. Składa się z dwóch gładkich warstw lnu i wypełnienia. Pikowanie jasnymi i brązowymi nićmi utworzyło obrazy, dodatkowo uwypuklone przez wprowadzenie pomiędzy warstwy bawełnianych włókien (technika trapunto). Jedna z części tego quiltu jest przechowywana w Victoria and Albert Museum w Londynie. Niewiele jednak wiadomo o patchworku i quiltingu przed wiekiem XVIII, i mało jest przykładów, które przetrwały do naszych czasów. -

Soft Glass – the Aesthetic Qualities of Kiln Formed Glass with Recycled Inclusions

SOFT GLASS – THE AESTHETIC QUALITIES OF KILN FORMED GLASS WITH RECYCLED INCLUSIONS SELINA-JAYNE TOPHAM A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Birmingham City University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2012 The Faculty of Art and Design, Birmingham Institute of Art and Design, Birmingham City University Abstract My research is about combining recycled materials with glass structures to produce textile artworks that have unique aesthetic qualities and a considerable lifespan. This thesis examines the technical development of kiln-formed glass voided structures, the aesthetic qualities of colour and softness and the effect of the research experience on my practice. The practical element of the research consisted of 18 experiments inspired by visits to the Seychelles and Barbados. The technical development was informed by concepts of being and non-being and by glass-making processes dating back to 1650 BC in Northern Mesopotamia, as well as fabric manipulation techniques thought to have originated in the fourteenth century in Sicily. Some 37 technical principles were discovered together with documented firing schedules that could be generalised to kiln-formed glass making. In terms of artwork aesthetics a methodology was developed that identified 32 qualities informed by colour theories. To eliminate errors in terminology the origins of each of these colour theories were identified and described using examples of artworks from living artists. The main aesthetic qualities identified were light/dark contrast, colour direction in terms of composition and optical colour mixing, with the latter being traced back to theory associated with early Christian glass mosaics. I also discovered how my roles of artist maker and researcher led to insights that contextualised my practice the most profound of which resulted from revisiting an experimental failure, which led to the identification of a new aesthetic quality of softness based on visual perception rather than tactile response. -

The Beginnings of Quilting and Patchwork in Antiquity - Two Articles on the History of the Craft Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE BEGINNINGS OF QUILTING AND PATCHWORK IN ANTIQUITY - TWO ARTICLES ON THE HISTORY OF THE CRAFT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Various | 34 pages | 15 Mar 2011 | Read Books | 9781446542347 | English | Alcester, United Kingdom The Beginnings of Quilting and Patchwork in Antiquity - Two Articles on the History of the Craft PDF Book Quilt making was taught to the young daughters in early days. Getting Started. Padded wear could be put on under armour to make it more comfortable, or even as a top layer for those who couldn't afford metal armour. For a time, the trend in wholecloth quilting was a preference for all-cotton white quilts. Obviously, quilting as a craft came to America with the early Puritans. Can I get hurt using a quilting machine? Playing on the word crazy they gave plans for "crazy" tea parties using mismatched invitations and other "crazy" themes. Wrap Up. This meant women no longer had to spend time spinning and weaving to provide fabric for their family's needs. In the lateth-century quilt revival, teachers like Elly Sienkiewicz repopularized the Baltimore Album style. Quilting in Modern Times Quilting has experienced a revival over the last 60 years. The wool wholecloth quilt was made in by Martha Crafts Howard. One of the most popular exhibits was the Japanese pavilion with its fascinating crazed ceramics and asymmetrical art. The story of a family was also commemorated in hand-pieced fabric. Essentially, a knee lifter is an attachable part that lets you control the position of a presser foot with your knee. Often these quilts provide the only decoration in a simply furnished home and they also were commonly used for company or to show wealth. -

Virtual Family Open Studios an Art Event Inspired by the Artwork of Anne Mudge and the William D. Cannon Art Gallery

SEGMENT 1 Overview of the Event with Laurette Garner, Community Arts Coordinator (Arts Education) Today’s Event Begins at 11AM Estimated Timeline- • Overview of the event • 11:05am Brief History of Quilting in the Arts & Artist Introduction • 11:10am Live from the Artist’s Studio with Barb Wills: demonstrating her art process & answering participant questions • 11:50am Art Kit Project Demonstration • 12:10pm Main Webinar Concludes/ Post-event Q & A with Presenters Any views and opinions expressed during events or in creative works are those of the artists and do not necessarily reflect the views of the City of Carlsbad. SEGMENT 2 Brief History of Quilting in the Arts with Lisa Naugler, Arts Instructor Images from the Material Pulses Gallery Exhibit Left: Elizabeth Brandt, The Habits of Being (detail), 2015 Middle: Mary Lou Alexander, Things Fall Apart #5, 2015 Right: Jane Willoughby, Veiled Connection (Side B), 2015 Tristan Quilt, originated Sicily, Italy c. 1360-1400 Silk Patchwork Coverlet, 1718, The Quilter’s Guild Museum Collection Quilting Bees through the ages Left to Right: 1880’s, 1930’s,1960’s Left: Photograph from Gee’s Bend, Alabama, c.1880 Middle: Annie Bendolph, Thousand Pyramids, 1930 Right: Willie “Ma Willie” Abrams, Roman Stripes Quilt, c. 1975 Faith Ringgold Middle: Echoes of Harlem, 1980 Right: Tar Beach, Women on a Bridge, #1 of 5, 1988 Nancy Crow Middle: Constructions #76, 2004 Right: Constructions #17, 1998 Left: Cleve Jones Middle: Panels from the AIDS Memorial Quilt Right: View of AIDS Memorial Quilt, Washington DC Sanford Biggers Middle: Lotus (125th), 2013 Right: Quilt No.19, “Rockstar”, 2013 Sherri Lynn Wood Middle: Disco Right: Wood’s Book: The Improv Handbook for Modern Quilters Quilting bees today! Meet the Artist Barb Wills is an award-winning fiber artist whose amazing quilts have been exhibited in galleries and museums throughout the United States, Europe, Russia, and Asia. -

April 2017 No

Heart and Home Quilters’ Guild www.heartandhomequiltersguild.org Next meeting April 18, 2017 Kutztown, PA 6:00 PM Kutztown April 2017 No. 252 Refreshments Message from the President The First quilt: The process of quilting April Warm winter...cold spring seems to be the weath- shows up in early Egypt and Feudal clothing. Virginia Conrad - sweet er pattern this year. Unfortunately, we had to No one really knows who used that process Judy Corl - savory cancel the March 15th meeting due to the snow the first time but the oldest quilt still around is Virginia Cusatis - savory storm the day before. Driving conditions would the Tristin Quilt at the Victoria and Albert Tracey Diehl - sweet not have been very good for the Wednesday Museum in London, England Margo Dufresne - sweet night meeting. Good news is that everyone had a The Tristan Quilt, sometimes called the Tris- Linda Dupler - sweet “sew day.” Pat took several “sew days” because tan and Isolde Quilt or the Guicciardini Quilt, Candace Edwards - savory of the snow storm. National Quilting Day was is one of the earliest surviving quilts in the Saturday the 18th. I hope all of you honored that world. Depicting scenes from the story of May day that was designated to represent all of you. Tristan and Isolde, an influential romance Linda Epler - sweet and tragedy, it was made in Sicily during the Kathy Fisher - savory Diane Hollenbach was able to reschedule second half of the 14th century (1360-1400). Eleanor Follweiler - sweet Michelle McLaughlin’s program for the April 19th There are at least two sections of the quilt, Maribeth Gardilla - savory meeting. -

DESIGN PRESENTATION Preface

‘TEXTILE HERITAGE INSPIRING CREATIVES-CREATEX’ EUROPEAN PROJECT OPEN CALL ANDREA SEBASTIANELLI_ DESIGN PRESENTATION Preface It is important to always keep in mind that while the verb “to archive” resembles the action of collecting records, the noun “archive” defines the physical place or ob- ject which contains those records. We can therefore argue that an archive is both the action of documenting the history and also the translation of it into a new object. I have been questioning myself for some- time now on how archives can be more easily experienced by everyone and there- fore transformed into an object that would reinvent its original identity. An object which will bring the archive out from the museums and turn it into new forms and functions. This double dimension has been my starting point for the following design research. A ground breaking initiatives in making archives more accessible is the digitaliza- tion that Museums and Privite collectors have been doing in the past years. By creating online databases, it became much easier for everybody to have access to their stored material. When it comes to textiles, and specifically to textile museums, the creation of online databases with textiles and fabrics make easier for researchers to study and conduct research on the field. Therefore, it can be argued that the digitalization of the archives promotes reproducibility and in- spires new developments and applications on the field. But how can a collection of objects can turn into a vehicle for the promotion of a museums’s online archive? 2 Creative Inspiration The development of my concept was inspired by three Our social identity is defined by the objects we are main projects: The new Acropolis Museum in Athens, surrounded. -

Index-1 99.Pdf

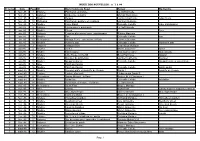

INDEX DES NOUVELLES : n° 1 à 99 N° revue Date Page ID Nom modèle ou Sujet Auteur Recherche 1 févr.-85 4 Histoire Patchwork et histoire Le Goff Armelle 1 févr.-85 5 Astuces Angles de coussins Morvan Dominique 1 févr.-85 6 Modèle Tulipes Lambert Catherine tulipe fleurs 1 févr.-85 10 Réflexion Patchwork, peinture et créations Lambert Suzanne 1 févr.-85 12 Modèle Cake Stand Delesalle Colettte cake stand panier 2 avr.-85 4 Histoire Fleurs dans le patchwork Le Goff Armelle 2 avr.-85 5 Modèle Fleurs fleur 2 avr.-85 7 Astuces Création d'un stencil pour matelassage Ribière Manuela 2 avr.-85 8 Modèle Sac Delesalle Colette sac 2 avr.-85 10 Rencontres Mangat Terrie - américaine à Paris Lambert Suzanne 2 avr.-85 16 Modèle Hunter's star Delesalle Colette Hunbter's star 3 juin-85 3 Astuces Enfilage facile Chalençon Monique 3 juin-85 4 Modèle Tortue Morel Jacqueline tortue 3 juin-85 6 Modèle Matelassage Chausson Jeanne matelassage 3 juin-85 7 Modèle Little house on the hill Buys Françoise maison 3 juin-85 8 Modèle Bouquet de printemps Lambert Catherine bouquet 3 juin-85 10 Modèle Stepping stones Delesalle Colette Stepping stones assemblage 3 juin-85 16 Idée Patch de l'amitié 3 juin-85 16 Modèle Patch de l'amitié Delesalle Colette patch amitié 4 sept.-85 4 Modèle Dresden plate ou assiette de Dresde Sarah ? assiette de Dresde 4 sept.-85 5 Histoire Histoire d'un quilt … Hedgecough Sarah B. 4 sept.-85 6 Rencontres James Michael : à Paris Boquet M. -

1 the Monthly

May 2018 Volume 1 Issue 5 the monthly cut Quilters’ Sew-Ciety of Redding President’s Message Vice President’s Message April showers bring May flowers. We are in the home stretch of pre- An old adage from an old person. paring for he Quilt Show. I want to Hope everyone is planning on at- thank everyone who has signed up tending the quilt show next week. to help before, during and after the You all have contributed in many show. I'm getting excited and can't ways-by assisting on the quilt show wait for opening day. Hope to see committee, volunteering at the each and every one of you there. show and contributing one or more quilts for display. I dropped Our May guild meeting will start at mine off today and they were 5:30 and will be our annual Philan- working like little bees in their thropic sew-in. There will be a na- hives. Promises to be a great show. cho bar provided, so bring your ma- chine and have a good time. I need to ask all members to please Inside be considerate when choosing Don't forget that we won't have the Masthead 2 snacks at the monthly meetings. It Saturday Sew-cial in April as we will 2018 Chairs 2 is meant to be a small snack at in- all be busy at the Quilt Show. We Community Quilts 3 termission and not dinner. Eat be- will resume the Sew-cial on May 19. Correspondence Secretary 3 fore you come. -

Thetrumpeter

In Muneris ut Somnium he rumpeter T T A Publication in Barony Bordermarch, Ansteorra August Being 2012 by common reckoning A.S.XLVII Premiere of the Sable Flur of Ansteorra Lord Biau-douz de la Mere awarded the new award The Sable Flur of Ansteorra by Their Royal Majesties, at The Steppes Artisan Event 2012. See pages 6-8 for more... Photo by HL KerMegan of Taransay, Barony of Elfsea. aaaaaTable of Contentsaaaaa Table of Content ..................................................................2 History of Quilting ..............................................................12 Officer Contact Information ..................................................3 From Tessa’s Garden to Hearth .........................................13 Baron/Baroness Words .......................................................4 Announcements ........................................................... 14-15 Calendar August ..................................................................5 Pear Wood .........................................................................15 The Sable Flur of Ansteorra ............................................. 6-8 Legendary Bordermarch Cabrito Spit ................................16 Round Table.........................................................................9 TRH Crowned/Hospitaler Report .......................................17 Pinch Bowls for BAM ....................................................10-11 Guilds Meetings !!!!NEW LISTINGS!!! .............................20 Contributors of Content HE Santiago, Baron -

CQG Newsletter October 2017.Pub

Coastlines Coastal Quilters Guild of Santa Barbara & Goleta, California Volume 29, No.4 October 2017 October Speakers: SB Modern Quilt Guild We are in for a real treat at the October meeting. Several members of the Santa Barbara Modern Quilt Guild (some of whom are also Coastal Quilters members) will share their journey into Modern Quilting and show quilts they have designed. About the Modern Quilt Guild: The MQG developed out of the thriving online community of modern quilters and their desire to meet in person. The founding guild was formed in Los Angeles in October 2009. The Santa Barbara MQG started in 2010 as an informal group meeting at the Fabric Quarter. Membership in the MQG was formalized in the summer of 2013; the SBMQG became a formal chapter and is now one of 170 guilds worldwide. There are approximately 12,000 members of the MQG--a small but diverse group of quilters from a variety of backgrounds. Reminder - the October workshop is an “Open Sew” day at Goleta Community Center. November Speaker/Workshop: Dora Cary At the November meeting, Romanian quilt designer Dora Cary of Orange Dot Quilts will share her love of making patterns and teaching quilting. Described as “fresh and original”, Dora’s patterns will be featured at the workshop the next day when m embers will make their choice of one of four Orange Dot patterns. Guild members who have taken a class with Dora say she’s a terrific teacher who gives a great workshop. Dora’s workshop patterns will be for sale at the meeting and can be downloaded from her website, www.etsy.com/shop/ OrangeDotQuilts . -

Introduction

1 Introduction The English word “museum” comes from the Latin word, and is pluralized as “museums” (or rarely, “musea”). It is originally from the Ancient Greek (Mouseion), which denotes a place or temple dedicated to the Muses (the patron divinities in Greek mythology of the arts), and hence a building set apart for study and the arts, especially the Musaeum (institute) for philosophy and research atAlexandria by Ptolemy I Soter about 280 BCE. The first museum/library is considered to be the one of Plato in Athens. However, Pausanias gives another place called “Museum,” namely a small hill in Classical Athens opposite the Akropolis. The hill was called Mouseion after Mousaious, a man who used to sing on the hill and died there of old age and was subsequently buried there as well. The Louvre in Paris France. 2 Museum The Uffizi Gallery, the most visited museum in Italy and an important museum in the world. Viw toward thePalazzo Vecchio, in Florence. An example of a very small museum: A maritime museum located in the village of Bolungarvík, Vestfirðir, Iceland showing a 19th-century fishing base: typical boat of the period and associated industrial buildings. A museum is an institution that cares for (conserves) a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic,cultural, historical, or scientific importance and some public museums makes them available for public viewing through exhibits that may be permanent or temporary. The State Historical Museum inMoscow. Introduction 3 Most large museums are located in major cities throughout the world and more local ones exist in smaller cities, towns and even the countryside.