A Best-First Anagram Hashing Filter for Approximate String Matching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hardware Pattern Matching for Network Traffic Analysis in Gigabit

Technische Universitat¨ Munchen¨ Fakultat¨ fur¨ Informatik Diplomarbeit in Informatik Hardware Pattern Matching for Network Traffic Analysis in Gigabit Environments Gregor M. Maier Aufgabenstellerin: Prof. Anja Feldmann, Ph. D. Betreuerin: Prof. Anja Feldmann, Ph. D. Abgabedatum: 15. Mai 2007 Ich versichere, dass ich diese Diplomarbeit selbst¨andig verfasst und nur die angegebe- nen Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Datum Gregor M. Maier Abstract Pattern Matching is an important task in various applica- tions, including network traffic analysis and intrusion detec- tion. In modern high speed gigabit networks it becomes un- feasible to search for patterns using pure software implemen- tations, due to the amount of data that must be searched. Furthermore applications employing pattern matching often need to search for several patterns at the same time. In this thesis we explore the possibilities of using FPGAs for hardware pattern matching. We analyze the applicability of various pattern matching algorithms for hardware imple- mentation and implement a Rabin-Karp and an approximate pattern matching algorithm in Endace’s network measure- ment cards using VHDL. The implementations are evalu- ated and compared to pure software matching solutions. To demonstrate the power of hardware pattern matching, an example application for traffic accounting using hardware pattern matching is presented as a proof-of-concept. Since some systems like network intrusion detection systems an- alyze reassembled TCP streams, possibilities for hardware TCP reassembly combined with hardware pattern matching are discussed as well. Contents vii Contents List of Figures ix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Motivation . 1 1.2 Related Work . 2 1.3 About Endace DAG Network Monitoring Cards . -

Comprehensive Examinations in Computer Science 1872 - 1878

COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATIONS IN COMPUTER SCIENCE 1872 - 1878 edited by Frank M. Liang STAN-CS-78-677 NOVEMBER 1078 (second Printing, August 1979) COMPUTER SCIENCE DEPARTMENT School of Humanities and Sciences STANFORD UNIVERSITY COMPUTER SC l ENCE COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATIONS 1972 - 1978 b Y the faculty and students of the Stanford University Computer Science Department edited by Frank M. Liang Abstract Since Spring 1972, the Stanford Computer Science Department has periodically given a "comprehensive examination" as one of the qualifying exams for graduate students. Such exams generally have consisted of a six-hour written test followed by a several-day programming problem. Their intent is to make it possible to assess whether a student is sufficiently prepared in all the important aspects of computer science. This report presents the examination questions from thirteen comprehensive examinations, along with their solutions. The preparation of this report has been supported in part by NSF grant MCS 77-23738 and in part by IBM Corporation. Foreword This report probably contains as much concentrated computer science per page as any document In existence - it is the result of thousands of person-hours of creative work by the entire staff of Stanford's Computer Science Department, together with dozens of h~ghly-talented students who also helped to compose the questions. Many of these questions have never before been published. Thus I think every person interested in computer science will find it stimulating and helpful to study these pages. Of course, the material is so concentrated it is best not taken in one gulp; perhaps the wisest policy would be to keep a copy on hand in the bathroom at all times, for those occasional moments when inspirational reading is desirable. -

Trusted Research Environments (TRE) a Strategy to Build Public Trust and Meet Changing Health Data Science Needs

Trusted Research Environments (TRE) A strategy to build public trust and meet changing health data science needs Green Paper v2.0 dated 21 July 2020 – For sign off Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Status of the document .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Overview .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Purpose ........................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Background .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 The case for TREs providing access to health data through safe settings ...................................................................... 8 Requirements for a Trusted Research Environment...................................................................................................10 Safe people ................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Safe projects ................................................................................................................................................................ -

A Personalized Cloud-Based Traffic Redundancy Elimination for Smartphones Vivekgautham Soundararaj Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2016 TailoredRE: A Personalized Cloud-based Traffic Redundancy Elimination for Smartphones Vivekgautham Soundararaj Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Soundararaj, Vivekgautham, "TailoredRE: A Personalized Cloud-based Traffic Redundancy Elimination for Smartphones" (2016). All Theses. 2387. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2387 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TailoredRE: A Personalized Cloud-based Traffic Redundancy Elimination for Smartphones A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Computer Engineering by Vivekgautham Soundararaj May 2016 Accepted by: Dr. Haiying Shen, Committee Chair Dr. Rong Ge Dr. Walter Ligon Abstract The exceptional rise in usages of mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets has contributed to a massive increase in wireless network traffic both Cellular (3G/4G/LTE) and WiFi. The unprecedented growth in wireless network traffic not only strain the battery of the mobile devices but also bogs down the last-hop wireless access links. Interestingly, a significant part of this data traffic exhibits high level of redundancy in them due to re- peated access of popular contents in the web. Hence, a good amount of research both in academia and in industries has studied, analyzed and designed diverse systems that attempt to eliminate redundancy in the network traffic. -

Branchclust Tutorial

BranchClust A Phylogenetic Algorithm for Selecting Gene Families Version 1.01 Tutorial http://www.bioinformatics.org/branchclust Copyright © Maria Poptsova and J. Peter Gogarten 2006-2007 Tutorial Selection of orthologous families with BranchClust is a multi-stage process that includes processing BLAST results, assembling superfamilies, alignment, reconstruction of phylogenetic trees, and applying the BranchClust method itself. Here we describe step-by- step procedures used for selection of orthologous families for a set of different taxa. All perl scripts described here are freely available and can be downloaded as one archive from the web-site: http://www.bioinformatics.org/branchclust/ All following procedures could be divided into 6 major stages: I. Downloading complete genomes and collection of significant hits II. Creation of taxa identification table III. Assemblage of superfamilies IV. Reconstruction of superfamily trees. V. Selection of orthologous families with BranchClust VI. Visualization of results with TreeDyn For all the programs described below, it is assumed that they are run from inside one directory. Perl-scripts create output files that are further used as input by other programs so that each step should be performed in order described in the tutorial. The scripts and programs were tested under both Mac OSX Darwin and Debian Linux operating sytems. Modules or standalone programs such as BioPerl, blastall, clustalw and treedyn need to be installed in the system. These programs are available from BioPerl – http://www.bioperl.org Blastall - http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/download.shtml Clustalw - http://bips.u-strasbg.fr/fr/Documentation/ClustalX/ TreeDyn - http://www.treedyn.org I. Downloading complete genomes and collection of significant hits 1. -

Approximate Pattern Matching with Index Structures

Technische Universität München Fakultät für Informatik Lehrstuhl für Effiziente Algorithmen a Approximatec e Pattern Matching b with Index Structuresd f Johannes Krugel a c b d c e d f e e e f a d e b c f Technische Universität München Fakultät für Informatik Lehrstuhl für Effiziente Algorithmen Approximate Pattern Matching with Index Structures Johannes A. Krugel Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät für Informatik der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Helmut Seidl Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Ernst W. Mayr 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Stefan Kramer, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz Die Dissertation wurde am 06.05.2015 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät für Informatik am 19.01.2016 angenommen. ii Zusammenfassung Ziel dieser Arbeit ist es, einen Überblick über das praktische Verhalten von Indexstrukturen und Algorithmen zur approximativen Textsuche (approximate pattern matching, APM) zu geben, abhängig von den Eigenschaften der Eingabe. APM ist die Suche nach Zeichenfolgen in Texten oder biologischen Sequenzen unter Berücksichtigung von Fehlern (wie z. B. Rechtschreibfehlern oder genetischen Mutationen). In der Offline-Variante dieses Problems kann der Text vorverarbeitet werden, um eine Indexstruktur aufzubauen bevor die Suchanfragen beantwortet werden. Diese Arbeit beschreibt und diskutiert praktisch relevante Indexstrukturen, Ähnlichkeitsmaÿe und Suchalgorithmen für APM. Wir schlagen einen neuen effizienten Suchalgorithmus für Suffixbäume im externen Speicher vor. Im Rahmen der Arbeit wurden mehrere Indexstrukturen und Algorithmen für APM implementiert und in einer Softwarebibliothek bereitgestellt; die Implementierungen sind effizient, stabil, generisch, getestet und online verfügbar. -

How to Think Like a Computer Scientist

How to Think Like a Computer Scientist Logo Version ii How to Think Like a Computer Scientist Logo Version Allen B. Downey Guido Gay Version 1.0 October 30, 2003 Copyright °c 2003 Allen B. Downey, Guido Gay. History: March 6, 2003: Allen B. Downey, How to Think Like a Computer Scientist. Java Version, fourth edition. October 30, 2003: Allen B. Downey, Guido Gay, How to Think Like a Com- puter Scientist. Logo Version, first edition. Permission is granted to copy, distribute, and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later ver- sion published by the Free Software Foundation; with Invariant Sections being “Preface”, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the appendix entitled “GNU Free Documentation License.” The GNU Free Documentation License is available from www.gnu.org or by writing to the Free Software Foundation, Inc., 59 Temple Place, Suite 330, Boston, MA 02111-1307, USA. The original form of this book is LATEX source code. Compiling this LATEX source has the effect of generating a device-independent representation of the book, which can be converted to other formats and printed. The LATEX source for this book is available from http://ibiblio.org/obp/thinkCS/ Prefazione Logo is a programming language mostly used as a teaching tool in primary education. If you know about its turtle graphics commands — such as repeat 10 [repeat 5 [fd 30 lt 72] lt 36] — you may be curious about its other capabilities. -

The Answer Question in Question Answering Systems Engenharia

The Answer Question in Question Answering Systems Andr´eFilipe Esteves Gon¸calves Disserta¸c~aopara obten¸c~aodo Grau de Mestre em Engenharia Inform´aticae de Computadores J´uri Presidente: Prof. Jos´eManuel Nunes Salvador Tribolet Orientador: Profa Maria Lu´ısaTorres Ribeiro Marques da Silva Coheur Vogal: Prof. Bruno Emanuel da Gra¸caMartins Novembro 2011 Acknowledgements I am extremely thankful to my Supervisor, Prof. Lu´ısaCoheur and also my colleague Ana Cristina Mendes (who pratically became my Co-Supervisor) for all their support throughout this journey. I could not have written this thesis without them, truly. I dedicate this to everyone that has inspired me and motivates me on a daily basis over the past year (or years) { i.e. my close friends, my chosen family. It was worthy. Thank you, you are my heroes. Resumo No mundo atual, os Sistemas de Pergunta Resposta tornaram-se uma resposta v´alidapara o problema da explos~aode informa¸c~aoda Web, uma vez que con- seguem efetivamente compactar a informa¸c~aoque estamos `aprocura numa ´unica resposta. Para esse efeito, um novo Sistema de Pergunta Resposta foi criado: Just.Ask. Apesar do Just.Ask j´aestar completamente operacional e a dar respostas corretas a um certo n´umerode quest~oes,permanecem ainda v´ariosproblemas a endere¸car. Um deles ´ea identifica¸c~aoerr´oneade respostas a n´ıvel de extra¸c~ao e clustering, que pode levar a que uma resposta errada seja retornada pelo sistema. Este trabalho lida com esta problem´atica,e ´ecomposto pelas seguintes tare- fas: a) criar corpora para melhor avaliar o sistema e o seu m´odulode respostas; b) apresentar os resultados iniciais do Just.Ask, com especial foco para o seu m´odulode respostas; c) efetuar um estudo do estado da arte em rela¸c~oesen- tre respostas e identifica¸c~aode par´afrases de modo a melhorar a extra¸c~aodas respostas do Just.Ask; d) analizar erros e detectar padr~oesde erros no mdulo de extra¸c~aode respostas do sistema; e) apresentar e implementar uma solu¸c~ao para os problemas detectados. -

Comparing Namedcapture with Other R Packages for Regular Expressions by Toby Dylan Hocking

CONTRIBUTED RESEARCH ARTICLE 328 Comparing namedCapture with other R packages for regular expressions by Toby Dylan Hocking Abstract Regular expressions are powerful tools for manipulating non-tabular textual data. For many tasks (visualization, machine learning, etc), tables of numbers must be extracted from such data before processing by other R functions. We present the R package namedCapture, which facilitates such tasks by providing a new user-friendly syntax for defining regular expressions in R code. We begin by describing the history of regular expressions and their usage in R. We then describe the new features of the namedCapture package, and provide detailed comparisons with related R packages (rex, stringr, stringi, tidyr, rematch2, re2r). Introduction Today regular expression libraries are powerful and widespread tools for text processing. A regular expression pattern is typically a character string that defines a set of possible matches in some other subject strings. For example the pattern o+ matches one or more lower-case o characters; it would match the last two characters in the subject foo, and it would not match in the subject bar. The focus of this article is regular expressions with capture groups, which are used to extract subject substrings. Capture groups are typically defined using parentheses. For example, the pattern [0-9]+ matches one or more digits (e.g. 123 but not abc), and the pattern [0-9]+-[0-9]+ matches a range of integers (e.g. 9-5). The pattern ([0-9]+)-([0-9]+) will perform matching identically, but provides access by number/index to the strings matched by the capturing sub-patterns enclosed in parentheses (group 1 matches 9, group 2 matches 5). -

The Power of Prediction: Cloud Bandwidth and Cost Reduction

The Power of Prediction: Cloud Bandwidth and Cost Reduction ∗ † Eyal Zohar Israel Cidon Osnat (Ossi) Mokryn Technion - Israel Institute of Technion - Israel Institute of Tel Aviv Academic College Technology Technology [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION In this paper we present PACK (Predictive ACKs), a novel end-to- Cloud computing offers its customers an economical and con- end Traffic Redundancy Elimination (TRE) system, designed for venient pay as you go service model, known also as usage-based cloud computing customers. pricing [6]. Cloud customers1 pay only for the actual use of com- Cloud-based TRE needs to apply a judicious use of cloud re- puting resources, storage and bandwidth, according to their chang- sources so that the bandwidth cost reduction combined with the ad- ing needs, utilizing the cloud’s scalable and elastic computational ditional cost of TRE computation and storage would be optimized. capabilities. Consequently, cloud customers, applying a judicious PACK’s main advantage is its capability of offloading the cloud- use of the cloud’s resources, are motivated to use various traffic re- server TRE effort to end-clients, thus minimizing the processing duction techniques, in particular Traffic Redundancy Elimination costs induced by the TRE algorithm. (TRE), for reducing bandwidth costs. Unlike previous solutions, PACK does not require the server to Traffic redundancy stems from common end-users’ activities, continuously maintain clients’ status. This makes PACK very suit- such as repeatedly accessing, downloading, distributing and modi- able for pervasive computation environments that combine client fying the same or similar information items (documents, data, web mobility and server migration to maintain cloud elasticity. -

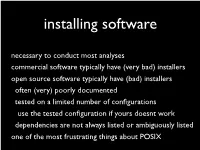

Necessary to Conduct Most Analyses Commercial Software Typically Have (Very Bad) Installers Open Source Software Typically Have

installing software necessary to conduct most analyses commercial software typically have (very bad) installers open source software typically have (bad) installers often (very) poorly documented tested on a limited number of configurations use the tested configuration if yours doesnt work dependencies are not always listed or ambiguously listed one of the most frustrating things about POSIX package managers installs executable (usually binary) and configuration files greatly simplifies installation and upgrades depends upon the (usually volunteer) package maintainers apt the Debian wrapper for dpkg used to install, update, remove, and purge packages will install dependencies for the target package http://packages.ubuntu.com/ if apt fails, try aptitude (the industrial strength version) apt sudo atp update updates the package cache sudo atp upgrade installs most upgrades sudo atp autoremove removes unneeded packages apt-cache search x searches repository for x apt-cache show x information for package x sudo apt install x installs package x sudo apt remove x removes package x sudo apt purge x removes package x and its files apt general use sudo atp update sudo atp upgrade sudo apt install scripts (interpreted code) simple scripts are placed in a directory listed in $PATH e.g. $HOME/bin dependencies must be satisfied interpreter interpreter extensions external programs environmental variables some interpreters (e.g. Perl, Python, JavaScript) have their own package management systems compiling… convert source code (text) into a (binary) executable file ./configure script that produces an appropriate MakeFile not required for all programs should indicate missing dependencies can set various options specify the (non–standard) location of a dependency set program specific options e.g. -

PARSING AS TREE TRAVERSAL Dale Gerdemann* Seminar Ffir Sprachwissenschaft, Universiti T T Bingen T

PARSING AS TREE TRAVERSAL Dale Gerdemann* Seminar ffir Sprachwissenschaft, Universiti t T bingen t ABSTRACT be eliminated, however, by employing a version of Greibach Normal Form which This paper presents a unified approach is extended to handle argument instan- to parsing, in which top-down, bottom- tiations in definite clause grammars. up and left-corner parsers m:e related The resulting parsers resemble the to preorder, postorder and inorder tree standard Prolog versions of versions of traversals. It is shown that the sim- such parsers. One can then go one step plest bottom-up and left-corner parsers further and partially execute the parser are left recursive and must be con- with respect to a particular grammar--- verted using an extended Greibach nor- as is normally done with definite clause mal form. With further partial exe- gra,,nn~a,'s (Per(,ir~ ~ Warren [JO]). a cution, the bottom-up and left-corner surprising result of this partial execu- parsers collapse togethe~ as in the I]IJP tion is l.ha.t the bottom-up and left- parser of Matsumoto. corner parsers become identical when they are 1)oth partially executed. This 1 INTRODUCTION may explain why the BUP parser of ~/lil.tSllll]OtO eta]. [6] [71 was ,'eferre.d tO In this paper, I present a unified ap- as a bottona-u I) parser even though it proach to parsing, in which top-down, clearly follows a left-corner strategy. bottom-up and left-corner parsers are related to preorder, postorder and in- TREE TRAVERSAL order tree traversals. To some extent, this connection is already clear since PRO G RAM S for each parsing strategy the nodes of Following O'Keefe [8], we can imple- the parse tree are constructed accord- ment i)reorder, postorder and inorder ing to the corresponding tree traversal.