Abraham's Righteousness and Sacrifice: Howto Understand (Andtranslate) Genesis 15 And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congratulations

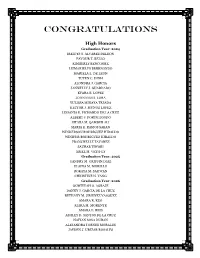

CONGRATULATIONS High Honors Graduation Year: 2024 IREIDYS Y. ALVAREZ DELEON FAVOUR T. BELLO KIMBERLY BENCOSME LIZMARIELYS BERREONDO MARIELA L. DE LEON TUYEN C. DINH ALONDRA J. GARCIA JANNELLY J. GUARDADO KYARA E. LOPEZ JOHNANGEL LORA YULISSA MINAYA TEJADA HECTOR J. MUNOZ LOPEZ LISSANIA E. PICHARDO DE LA CRUZ ALBERT J. PORTUHONDO SITARA M. QAMBER ALI MARIA E. RAMOS SABAN WINDERSON RODRIGUEZ HIRALDO WINIFER RODRIGUEZ HIRALDO FRANCHELLE TAVAREZ SAURAB TIWARI ARIEL M. VETH-LY Graduation Year: 2025 YANDRY M. GRIFFIN DIAZ ELAINA M. MORILLO ROKAYA M. SAHWAN CHRISTINE N. YANG Graduation Year: 2026 QOWIYYAH O. AGBAJE DANNY J. GARCIA DE LA CRUZ BETHANY M. JIMENEZ VASQUEZ AMARA R. KEO KIARA M. MORENTE AMARA E. REIS ASHLEY D. SANTOS DE LA CRUZ NAIYAN SOSA DURAN ALEJANDRA TORNES MORALES JAYDEN J. URIZAR ROSALES Honors Graduation Year: 2024 JOSELYN E. ALONZO XAVIEA S. BROWN PRECIOUS F. BUWEE WILBERT CABRAL GARCIA KALIYAN N. CHHUN JUANA CHIJAL JESSICA A. CHOCOJ CHALI DOMINGO COLAJ COLAJ MARIALYS I. CRUZ ASHLEY M. DE LA CRUZ ARIAS ARDENIS J. DEL ROSARIO GIANA N. DICENZO BRIANNA M. DOMINGUEZ FRIAS SOMALY DONG OSMERY ESTRELLA VARGAS ERICA O. FELIX HERRERA EDUARDO J. GIL ALFONSO BRYAN M. GIRON LUX VILMA GODINEZ SEBASTIANA JERONIMO ALONZO HENRY L. JOHNSON IV TATYANA JOHNSON KRISSBEILY MARTE FERREIRA GEARA D. MATOS DIEGO A. NAVAS ORTES OLIVIER NGABONZIZA MANUELA NUNEZ HERNANDEZ AMBER K. O'BRIEN NICERLIS OLIVO NUNEZ ANDERSON E. ORTEGA-LOPEZ YENEDELI E. PENA GUZMAN FRANCISCO PEREZ RAMOS RENE G. REYES EMILY A. RINDA BETHZY M. ROBLES URIZAR CRISTIAN D. ROSALES HERNANDEZ JASON S. RUSH JAMES D. SEFFENS III GENESIS SOSA ALEXANDER SUAREZ LIZZETTE M. -

Evaluation & Research Literature: the State of Knowledge on BJA

Evaluation & Research Literature: The State of Knowledge on BJA-Funded Programs March 27, 2015 Overview The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) is a leader in developing and implementing evidence-based criminal justice policy and practice. BJA’s mission is to provide leadership in services and grant administration and criminal justice policy development to support local, state, and Tribal justice strategies to achieve safer communities. This is accomplished in many criminal justice topic areas, including adjudication, corrections, counter-terrorism, crime prevention, justice information sharing, law enforcement, justice and mental health, substance abuse, and Tribal justice. Under each topic area, BJA funds numerous programs and initiatives at the Tribal, local, and state level. In partnership with the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), other Federal partners, and many other research partners, many of these programs have been evaluated, while others have not. The intent of the following report is to assess the state of knowledge as determined by data collection, research, and evaluation of and related to BJA- funded programs. This report is a resource that can be a reference for both evaluation and research literature on many BJA programs. It also identifies programs and practices for which U.S. Department of Justice resources have played a critical role in generating innovative programs and sound practices. This report identifies programs and practices with a solid foundation of evidence, as well as those that may benefit from further research and evaluation. Program evaluation is a systematic, objective process for determining the success of a policy or program. Evaluations assess whether and to what extent the program is achieving its goals and objectives. -

TOUR DE FER 20 Colour: Greens of the Stone Age / Weight: 14.80Kg

TOUR DE FER 20 Colour: Greens Of The Stone Age / Weight: 14.80Kg SPECS Frame Reynolds 725 Heat-Treated Chromoly FEATURES Fork Genesis Full Chromoly - Reynolds 725 CrMo tubeset. Headset PT-1770 EC34 Upper / EC34 Lower - Shimano 3x10 speed drivetrain. Hanger Integraded - Shimano dynamo hub with B&M lights. COMPONENTS - Schwalbe Marathon touring tyres. Handlebars Genesis Alloy 18mm Rise, 8 Deg Backsweep, XS = 580mm, S/M = 600mm, L/XL = 620mm - Mudguards included. Stem Genesis Alloy, 31.8mm, -6 Deg, 100mm - Tubus rear rack, Atranvelo front rack. Grips/Tape Genesis Vexgel Saddle Genesis Adventure Seatpost Genesis Alloy 27.2mm XS/S/M = 350mm, L/XL = 400mm Pedals NW-99k With Cage DRIVE TRAIN Shifters Shimano Deore SL-M6000 3x10spd GEOMETRY XS S M L XL Rear Derailleur Shimano Deore RD-M6000-SGS Seat Tube 450 480 510 530 570 Front Derailleur Shimano Deore FD-T6000-L-3 Top Tube 533 547 578 604 636 Chainset Shimano FC-T611 44/32/24t, 170mm Frame Reach 365 375 395 415 435 BB Shimano BB-ES300 Frame Stack 566 580 599 618 637 Chain KMC X10 Head Tube 125 140 160 180 200 Cassette Shimano CS-HG500 11-34t Head Angle 71 71 71 71 71 BRAKES Seat Angle 73.5 73.5 73 73 72.5 Brakes Promax DSK-717RA Chainstay 455 455 455 455 455 Brake Levers Promax XL-91 BB Drop 75 75 75 75 75 Rotors Promax DT-160G, 160mm, 6 bolt Wheelbase 1041 1056 1083 1109 1136 WHEELS & TYRES Fork Offset 55 55 55 55 55 Rims Sun Ringle Rhyno Lite Standover 758 778 799 807 843 Hubs Shimano Front - DH-3D37 Dynamo Hub / Rear - FH-M4050 Stem 100 100 100 100 100 Spokes Steel 14g Handlebar 580 600 600 620 620 Tyres Schwalbe Marathon, 700 x 37c Crankarm 170 170 170 170 170 * The image above is for illustration purposes only. -

Incorporated Righteousness: a Response to Recent Evangelical Discussion Concerning the Imputation of Christ’S Righteousness in Justification

JETS 47/2 (June 2004) 253–75 INCORPORATED RIGHTEOUSNESS: A RESPONSE TO RECENT EVANGELICAL DISCUSSION CONCERNING THE IMPUTATION OF CHRIST’S RIGHTEOUSNESS IN JUSTIFICATION michael f. bird* i. introduction In the last ten years biblical and theological scholarship has witnessed an increasing amount of interest in the doctrine of justification. This resur- gence can be directly attributed to issues emerging from recent Protestant- Catholic dialogue on justification and the exegetical controversies prompted by the New Perspective on Paul. Central to discussion on either front is the topic of the imputation of Christ’s righteousness, specifically, whether or not it is true to the biblical data. As expected, this has given way to some heated discussion with salvos of criticism being launched by both sides of the de- bate. For some authors a denial of the imputation of Christ’s righteousness as the sole grounds of justification amounts to a virtual denial of the gospel itself and an attack on the Reformation. Others, by jettisoning belief in im- puted righteousness, perceive themselves as returning to the historical mean- ing of justification and emancipating the Church from its Lutheranism. In view of this it will be the aim of this essay, in dialogue with the main pro- tagonists, to seek a solution that corresponds with the biblical evidence and may hopefully go some way in bringing both sides of the debate together. ii. a short history of imputed righteousness since the reformation It is beneficial to preface contemporary disputes concerning justification by identifying their historical antecedents. Although the Protestant view of justification was not without some indebtedness to Augustine and medieval reactions against semi-Pelagianism, for the most part it represented a theo- logical novum. -

Righteousness of God: Ability to Live Christian Holiness

D. Matijević: Righteousness of God: Ability to Live Christian Holiness Righteousness of God: Ability to Live Christian Holiness Dalia Matijević Church of the Nazarene in Zagreb, Croatia [email protected] UDK 27-1;2-184;2-426 Review paper DOI: https://doi.org/10.32862/k.12.2.5 Abstract The purpose of this article is to provide insight to what extent our concep- tualization of the dikaiosyne theou shapes our way of understanding our- selves as Christians being the Body of Christ and living holy lives. Strongly influenced by the epistle to the Romans, we perceive holiness as being in right relation to God and righteousness being a practical consequence of this relati- onship. Holiness as the inner nature of God brings fruits of His righteousness, which is God’s saving activity. However, in the light of Christ and his sacrifi- cial death and resurrection, relational, and eschatological perspectives of the dikaiosyne theou concept become crucial. This concept stands at the heart of Paul’s gospel and anticipates several layers of meaning, primarily God’s redeeming and saving activity, but also covenan- tal faithfulness and restorative justice brought by God and made available for all. Wider perspective is provided through the faithfulness of Jesus and his obedience to the Father in fulfilling salvific purposes. For us, it means a tran- sformational and relational way of living in an eschatological perspective. Christian ethics are deeply grounded in the concept of dikaiosyne theou, and Christian conduct represents its practical and necessary expression. People living in genuine Christian community are marked by the righteousness of God expressed as agape and progressively transformed by the presence and involvement of his Holy Spirit. -

The Inspiration and Truth of Sacred Scripture

The Inspiration and Truth of Sacred Scripture The Inspiration and Truth of Sacred Scripture The Word That Comes from God and Speaks of God for the Salvation of the World Pontifical Biblical Commission Translated by Thomas Esposito, OCist, and Stephen Gregg, OCist Reviewed by Fearghus O’Fearghail Foreword by Cardinal Gerhard Ludwig Müller LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org This work was translated from the Italian, Inspirazione e Verità della Sacra Scrittura. La parola che viene da Dio e parla di Dio per salvare il mondo (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2014). Cover design by Jodi Hendrickson. Cover photo: Dreamstime. Excerpts from documents of the Second Vatican Council are from The Docu- ments of Vatican II, edited by Walter M. Abbott, SJ (New York: The America Press, 1966). Unless otherwise noted, Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible © 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. © 2014 by Pontifical Biblical Commission Published by Liturgical Press, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Control Number: 2014937336 ISBN: 978-0-8146-4903-9 978-0-8146-4904-6 (ebook) Table of Contents Foreword xiii General Introduction xvii I. -

2010 Hyundai Genesis

2010 HYUNDAI_GENESIS If you’re reading this brochure, chances are you’re the kind of automotive enthusiast who, instead of simply opening your wallet and adding a status trophy to your garage, prefers to open something else: Your mind. It’s a refreshing attitude that often leads you to discover truly rewarding experiences, from new and unexpected sources. Like Genesis, from Hyundai. Nobody was looking for Hyundai to build a luxury car that would challenge the automotive elite. But we did. Nobody expected us to benchmark the industry’s best, then apply the art and science needed to meet those marks. But we did. Nobody thought we’d charm the pants off a jury of North America’s most esteemed automotive journalists, or be named "The Most Appealing Midsize Premium Car" in 2009 by J.D. Power and Associates.1 But we did. And by doing what few people expected of us, we now find ourselves as a car company that a lot of people are starting to think about in a whole new way. It’s 2010. Welcome to Hyundai. 1 The Hyundai Genesis received the highest numerical score among midsize premium cars in the proprietary J.D. Power and Associates 2009 Automotive Performance Execution and Layout Study.SM Study based on responses from 80,930 new-vehicle owners, measuring 245 models and measures opinions after 90 days of ownership. Proprietary study results are based on experiences and perceptions of owners surveyed in February-May 2009. Your experiences may vary. Visit jdpower.com. geNesIS 3.8 IN TItaNIUM GRay metallIC MEASURE GENESIS AGAINST OTHER LUXURY SEDANS. -

“Christ Our Righteousness: Paul's Theology of Justification”

“Christ our Righteousness: Paul’s Theology of Justification” By Mark A. Seifrid Inter Varsity Press, New Studies in Biblical Theology, 2000 $ 19.99, 222 pages (paper) ________________________________________ Readers of Modern Reformation certainly will be interested in any book which sets forth Paul’s doctrine of justification and its relationship to the law of God. This is especially true when such a study is conducted in light of the challenges raised to traditional Protestant formulations of this critical doctrine by proponents of the so-called “New Perspective on Paul” (NPP) such as E. P. Sanders and James D. G. Dunn. Christ our Righteousness by Mark Seifrid is such a book. Associate professor of New Testament at the Southern Baptist Seminary in Louisville, Dr. Seifrid is among a group of evangelical scholars widely hailed for their substantial contributions to Pauline studies. Other names which come to mind in this regard are: Douglas Moo, Frank Thielman and Thomas Schreiner. Seifrid has already written a substantial volume on Paul, Justification by faith: The Origin and Development of a Central Pauline Theme (E. J. Brill, 1992), and an important essay on the subject of Romans 7:14-25 in Novum Testamentum (Vol. 34, 1992). He is the author of an insightful review of The Gift of Salvation which originally appeared in First Things (1997) as the fruit on the ongoing evangelical-Roman Catholic discussion about the nature of the gospel (Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society Vol. 42). When someone with Seifrid’s pedigree weighs in on Paul, justification and the law, it is important to take notice. -

Attitudes and Psychographic Data Get Inside the Mind of Your Consumers Audience Guide Attitudes and Psychographic Data

Audience Guide Attitudes and Psychographic data Get inside the mind of your consumers Audience Guide Attitudes and Psychographic Data Target consumers by their state of mind Diverse categories To more successfully target the right individuals and engage them with messages that will resonate, • Leverage these pre-built audiences across nine marketers need to look into the consumer’s heart and mind. major categories based on the not-so-visible Our psychographic audiences offer marketers the ability to characteristics that have significant impact on target consumers across an array of audiences that are consumer buying decisions. Or you can build a based on who the person is and what they believe. The custom audience and layer in other attributes to reach an even more precise audience. highly revealing, in-depth segments take into account a consumer’s attitudes, expectations, behaviors, lifestyles, purchase habits and media preferences. Audience snapshot The psychographic audience segments are modeled from • Impulse Buyer: Reach consumers who change Experian's trusted Simmons National Consumer Study, a brands for the sake of variety and novelty. They often buy things on the spur of the moment. syndicated survey of 20,000 American adults that is used day-in and day-out by marketers, agencies and media • Health and Image Leader: Reach consumers who are likely to try any new health and companies to help them better understand consumer nutrition products or diets. They are a regular motivations and identify the most appropriate media source of health information for others. through which to reach them Page 2 | Attitudes and Psychographic Data Audience Guide Attitudes and Psychographic Data Environment Behavioral Greens Reach consumers likely to think and act green. -

In Silence Genesis 22 Some of Life's Deepest Mysteries Are Examined In

In Silence Genesis 22 Some of life’s deepest mysteries are examined in Bible stories. Through the centuries, for example, many have tried to make sense out of the narrative recorded in Genesis 22, one of the darkest, most difficult stories that humans have ever told each other. This account begins with a shout. It’s only one word long. Abraham is at home with his wife, his servants. We don’t know what he’s doing at this moment. It’s probably an ordinary day. When suddenly Abraham hears a voice. The voice says to him one word: “Abraham!” This is not just a voice. This is the voice of God, the Creator of the Universe calling to one man, to Abraham. Not for the first time, not at all. When Abraham was younger, God appeared to him and told him to leave his home, which Abraham did. And then God told Abraham to go to a strange land, which he did. And then God and Abraham exchanged promises, and made a covenant together, and God told Abraham to send his first son Ishmael away into the desert, which Abraham did. And then God told Abraham that he had a plan to destroy the people of Sodom and Gomorrah. This time Abraham argued with God. They went back and forth – Abraham and God. “Can’t we save those cities, or some people in those cities, or anyone in those cities?” Later God sent angels to tell of the coming of Isaac. So it wasn’t completely out of the ordinary when God came to where Abraham was and called to him. -

Religion and Realpolitik: Reflections on Sacrifice

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 11-2014 Religion and Realpolitik: Reflections on Sacrifice Carolyn Marvin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons, Other Religion Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Marvin, C. (2014). Religion and Realpolitik: Reflections on Sacrifice. Political Theology, 15 (6), 522-535. https://doi.org/10.1179/1462317X14Z.00000000097 Preprint version. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/375 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Religion and Realpolitik: Reflections on Sacrifice Abstract Enduring groups that seek to preserve themselves, as sacred communities do, face a structural contradiction between the interests of individual group members and the survival interests of the group. In addressing existential threats, sacred communities rely on a spectrum of coercive and violent actions that resolve this contradiction in favor of solidarity. Despite different histories, this article argues, nationalism and religiosity are most powerfully organized as sacred communities in which sacred violence is extracted as sacrifice from community members. The exception is enduring groups that are able to rely on the protection of other violence practicing groups. The argument rejects functionalist claims that sacrifice guarantees solidarity or survival, since sacrificing groups regularly fail. In a rereading of Durkheim’s totem taboo, it is argued that sacred communities cannot survive a permanent loss of sacrificial assent on the part of members. Producing this assent is the work of ritual socialization. The deployment of sacrificial violence on behalf of group survival, though deeply sobering, is best constrained by recognizing how violence holds sacred communities in thrall rather than by denying the links between them. -

War and Sacrifice in the Post-9/11 Era

Social & Demographic Trends October 5, 2011 The Military-Civilian Gap War and Sacrifice in the Post-9/11 Era FOR FURTHER INFORMATION, CONTACT Pew Social & Demographic Trends Tel (202) 419-4372 1615 L St., N.W., Suite 700 Washington, D.C. 20036 www.pewsocialtrends.org PREFACE America’s post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are unique. Never before has this nation been engaged in conflicts for so long. And never before has it waged sustained warfare with so small a share of its population carrying the fight. This report sets out to explore a series of questions that arise from these historical anomalies. It does so on the strength of two nationwide surveys the Pew Research Center conducted in the late summer of 2011, as the 10th anniversary of the start of the war in Afghanistan approached. One survey was conducted among a nationally representative sample of 1,853 military veterans, including 712 who served on active duty in the period after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. The other was among a nationally representative sample of 2,003 American adults. The report compares and contrasts the attitudes of post-9/11 veterans, pre-9/11 veterans and the general public on a wide range of matters, including sacrifice; burden sharing; patriotism; the worth of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq; the efficiency of the military and the effectiveness of modern military tactics; the best way to fight terrorism; the desirability of a return of the military draft; the nature of America’s place in the world; and the gaps in understanding between the military and civilians.