Digital Songlines: the Adaption of Modern Communication Technology at Yuendemu, a Remote Aboriginal Community in Central Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submission to the Enquiry of the House Of

SUBMISSION TO THE INQUIRY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEE ON COMMUNICATIONS INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND THE ARTS INTO COMMUNITY BROADCASTING Submission 80 FROM THE NATIONAL INDIGENOUS TELEVISION (NITV) COMMITTEE Executive Summary In September 2005 the Australian Government announced that from 1 July 2006 it will fund the establishment of an Indigenous television service. The National Indigenous Television (NITV) Committee1 is charged with the implementation of the new service; provisionally named National Indigenous Television (NITV). The NITV Committee proposes that NITV, as a fully fledged, government licenced broadcast service, should be provided with the same digital spectrum access as the other mainstream broadcasters. Such an allocation would provide an opportunity for NITV to act as a “channel multiplexer” to provide digital carriage of local community broadcasters. This would allow the community services to continue to be provided with spectrum “free of charge”, without the need for them to provide their own expensive technical infrastructure for digital services. 1 See Appendix 1 for NITV Committee members. The NITV Committee is a voluntary, industry representative group which was formed by the Australian Indigenous Communications Association (AICA) to develop an effective strategy for the establishment of a national Indigenous television service. The group comprises representatives from AICA, Indigenous Remote Communications Association Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Corporation (IRCA), Indigenous Screen Australia (ISA), IMPARJA Television and those with specific contributing industry expertise. Submission The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Communications Information Technology and The Arts is conducting an enquiry into community broadcasting and seeks input from involved organisations on:- • The scope and role of community broadcasting • Content and programming requirements • Technological opportunities • Opportunities and threats to achieving a diverse and robust network of community broadcasters 1. -

DEADLYS® FINALISTS ANNOUNCED – VOTING OPENS 18 July 2013 Embargoed 11Am, 18.7.2013

THE NATIONAL ABORIGINAL & TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER MUSIC, SPORT, ENTERTAINMENT & COMMUNITY AWARDS DEADLYS® FINALISTS ANNOUNCED – VOTING OPENS 18 July 2013 Embargoed 11am, 18.7.2013 BC TV’s gripping, award-winning drama Redfern in the NBA finals, Patrick Mills, are finalists in the Male Sportsperson Now is a multiple finalist across the acting and of the Year category, joining two-time world champion boxer Daniel television categories in the 2013 Deadly Awards, Geale, rugby union’s Kurtley Beale and soccer’s Jade North. with award-winning director Ivan Sen’s Mystery Across the arts, Australia’s best Indigenous dancers, artists and ARoad and Satellite Boy starring the iconic David Gulpilil. writers are well represented. Ali Cobby Eckermann, the SA writer These were some of the big names in television and film who brought us the beautiful story Ruby Moonlight in poetry, announced at the launch of the 2013 Deadlys® today, at SBS is a finalist with her haunting memoir Too Afraid to Cry, which headquarters in Sydney, joining plenty of talent, achievement tells her story as a Stolen Generations’ survivor. Pioneering and contribution across all the award categories. Indigenous award-winning writer Bruce Pascoe is also a finalist with his inspiring story for lower primary-school readers, Fog Male Artist of the Year, which recognises the achievement of a Dox – a story about courage, acceptance and respect. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander musicians, will be a difficult category for voters to decide on given Archie Roach, Dan Sultan, The Deadly Award categories of Health, Education, Employment, Troy Cassar-Daley, Gurrumul and Frank Yamma are nominated. -

Mount Lyell Abt Railway Tasmania

Mount Lyell Abt Railway Tasmania Nomination for Engineers Australia Engineering Heritage Recognition Volume 2 Prepared by Ian Cooper FIEAust CPEng (Retired) For Abt Railway Ministerial Corporation & Engineering Heritage Tasmania July 2015 Mount Lyell Abt Railway Engineering Heritage nomination Vol2 TABLE OF CONTENTS BIBLIOGRAPHIES CLARKE, William Branwhite (1798-1878) 3 GOULD, Charles (1834-1893) 6 BELL, Charles Napier, (1835 - 1906) 6 KELLY, Anthony Edwin (1852–1930) 7 STICHT, Robert Carl (1856–1922) 11 DRIFFIELD, Edward Carus (1865-1945) 13 PHOTO GALLERY Cover Figure – Abt locomotive train passing through restored Iron Bridge Figure A1 – Routes surveyed for the Mt Lyell Railway 14 Figure A2 – Mount Lyell Survey Team at one of their camps, early 1893 14 Figure A3 – Teamsters and friends on the early track formation 15 Figure A4 - Laying the rack rail on the climb up from Dubbil Barril 15 Figure A5 – Cutting at Rinadeena Saddle 15 Figure A6 – Abt No. 1 prior to dismantling, packaging and shipping to Tasmania 16 Figure A7 – Abt No. 1 as changed by the Mt Lyell workshop 16 Figure A8 – Schematic diagram showing Abt mechanical motion arrangement 16 Figure A9 – Twin timber trusses of ‘Quarter Mile’ Bridge spanning the King River 17 Figure A10 – ‘Quarter Mile’ trestle section 17 Figure A11 – New ‘Quarter Mile’ with steel girder section and 3 Bailey sections 17 Figure A12 – Repainting of Iron Bridge following removal of lead paint 18 Figure A13 - Iron Bridge restoration cross bracing & strengthening additions 18 Figure A14 – Iron Bridge new -

'Noble Savages' on the Television

‘Nobles and savages’ on the television Frances Peters-Little The sweet voice of nature is no longer an infallible guide for us, nor is the independence we have received from her a desirable state. Peace and innocence escaped us forever, even before we tasted their delights. Beyond the range of thought and feeling of the brutish men of the earli- est times, and no longer within the grasp of the ‘enlightened’ men of later periods, the happy life of the Golden Age could never really have existed for the human race. When men could have enjoyed it they were unaware of it and when they have understood it they had already lost it. JJ Rousseau 17621 Although Rousseau laments the loss of peace and innocence; little did he realise his desire for the noble savage would endure beyond his time and into the next millennium. How- ever, all is not lost for the modern person who shares his bellow, for a new noble and savage Aborigine resonates across the electronic waves on millions of television sets throughout the globe.2 Introduction Despite the numbers of Aboriginal people drawn into the Australian film and television industries in recent years, cinema and television continue to portray and communicate images that reflect Rousseau’s desires for the noble savage. Such desires persist not only in images screened in the cinema and on television, but also in the way that they are dis- cussed. The task of ridding non-fiction film and television making of the desire for the noble and the savage is an essential one that must be consciously dealt with by both non- Aboriginal and Aboriginal film and television makers and their critics. -

Mckee, Alan (1996) Making Race Mean : the Limits of Interpretation in the Case of Australian Aboriginality in Films and Television Programs

McKee, Alan (1996) Making race mean : the limits of interpretation in the case of Australian Aboriginality in films and television programs. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4783/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Making Race Mean The limits of interpretation in the case of Australian Aboriginality in films and television programs by Alan McKee (M.A.Hons.) Dissertation presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Glasgow in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Glasgow March 1996 Page 2 Abstract Academic work on Aboriginality in popular media has, understandably, been largely written in defensive registers. Aware of horrendous histories of Aboriginal murder, dispossession and pitying understanding at the hands of settlers, writers are worried about the effects of raced representation; and are always concerned to identify those texts which might be labelled racist. In order to make such a search meaningful, though, it is necessary to take as axiomatic certain propositions about the functioning of films: that they 'mean' in particular and stable ways, for example; and that sophisticated reading strategies can fully account for the possible ways a film interacts with audiences. -

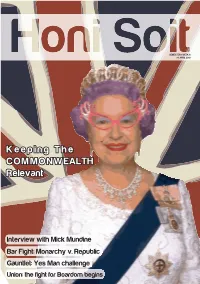

Keeping the COMMONWEALTH Relevant

SEMESTER 1 WEEK 6 14 APRIL 2010 Keeping The COM MONWEALTH Relevant Interview with Mick Mundine Bar Fight: Monarchy v. Republic Gauntlet: Yes Man challenge Union: the fight for Boardom begins 2 This Week's: Things we regret typingCONTENTS into Google Images: Legs Akimbo BACK FROM EASTER BREAK Best Haircut: Lin Yu Chun’s astonishing bowlcut. His performance of “I HONI SOIT, EDITION 5 Will Always Love You” is similarly breathtaking. 14 APRIL 2010 Somewhat Racsist Youtube Video Of the Week: “Giant Hole”, the Enlgish “translation” of A.R. Rahman’s “Jai Ho” The Profile TOO MUCH CHOCOLATE Carmen Culina and Tony Mundine get 09 The Post 03 chummy. Missives or Epistles? The Arts-Hole The fight for the best synonym for letters 10 Bridie Connellan felt the attraction of the continues. The Uni-Cycle Edward Sharpe & Magnetic Zeros. 04 Hannah Lee thinks superheroes should stay Sheenal Singh has a bad back. superheroey. Tim Whelan topped the state in Frogger on the Ruby Prosser does not want to hear about ATAR. how “hectic” Stereosonic was. Elle Jones went to Easter mass and a debating Aleks Wansbrough tries a little tenderness. competition. In short, a mass... Daniel Zwi goes Cloud watching. Mekela Panditharatne got diplomatic in Diana Tjoeng develops Stockholm Syndrome. Taipei.Which is more than can be said for the Chinese. David Mulligan caused some public nuisance at Law Camp. The Mains 12 The Lodgers 06 Nicole Buskiewicz spent two hours with WHY ARE YOU WEARING THAT Ted Talas got wet at a college event.The annual the Queen. STUPID EASTER SUIT? intercol rowing regatta. -

Trachoma Arts-Based Health Promotion Brings Hygiene to Life in Remote Indigenous Communities

Trachoma arts-based health promotion brings hygiene to life in remote Indigenous communities 13th National Rural Health Conference Darwin NT May 2015 The arts and health Creating arts and health experiences to improve community and individual health and wellbeing. The arts have been used and well documented in primary health and acute care, in community health at any point in the health care continuum In creatively birthing and ageing For mental health For race, gender, sexuality and religious inclusion In death and dying across urban, regional rural and remote Australia There is clear empirical evidence that arts and health activity is a health-promoting endeavour for all members of society. Australian National Arts and Health Framework 2013 Indigenous Australian children are born with better eyesight than non-Indigenous children Indigenous Australian adults experience 6 x blindness Taylor HR, et al., National Indigenous Eye Health Survey - Minum Barreng (Tracking Eyes). 2009, Melbourne: Indigenous Eye Health Unit, Melbourne School of Population Health in collaboration with the Centre for Eye Research Australia and the Vision CRC. Trachoma • Major cause of preventable blindness globally • Australia only high income country • WHO Alliance for Global Elimination by 2020 • Developing countries declared/declaring elimination Oman, Ghana, Morocco, Iran, Vietnam, Myanmar, Gambia, Ghana Around 232 million people live in trachoma endemic areas of 53 countries and need treatment. www.trachomaatlas.org Stages of trachoma It is a hygiene related disease It will be eliminated by 2020 Trachoma in Australia Causes 9% blindness and vision loss in Indigenous Australians Active trachoma in remote Indigenous communities – later stages around the country Limited and overcrowded housing, lack of safe and functional washing facilities, poor personal and community hygiene Spreads from child to child, shared sleeping spaces, dirty faces Children’s eye, nose, ear secretions common and normalised Trachoma • Eliminated with the WHO S.A.F.E. -

The Arts- Media Arts

Resource Guide The Arts- Media Arts The information and resources contained in this guide provide a platform for teachers and educators to consider how to effectively embed important ideas around reconciliation, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and contributions, within the specific subject/learning area of The Arts- Media Arts. Please note that this guide is neither prescriptive nor exhaustive, and that users are encouraged to consult with their local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, and critically evaluate resources, in engaging with the material contained in the guide. Page 2: Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts Page 4: Timeline of Key Dates in the Contemporary History of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts Page 8: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts and Artists— Television Page 10: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts and Artists— Film Page 14: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts and Artists— Newspaper, Magazine and Comic Book Page 15: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts and Artists— Radio Page 17: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts and Artists— Apps, Interactive Animations and Video Games Page 19: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts and Artists—The Internet Page 21: Celebratory Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Media Arts Events Page 22: Other Online Guides/Reference Materials Page 23: Reflective Questions for Media Arts Staff and Students Please be aware this guide may contain references to names and works of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that are now deceased. External links may also include names and images of those who are now deceased. -

The Adaption of Modern Communication Technology at Yuendemu, a Remote Aboriginal Community in Central Australia

Digital Songlines: the adaption of modern communication technology at Yuendemu, a remote Aboriginal Community in Central Australia by Lydia Buchtmann A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters ofArts (Research) in Communication at the University of Canberra April 2000 AKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks to: The Warlpiri and Pitjantjatjara people for their hospitality and willingness to share their achievements with me. Tom Kantor, Declan O'Gallagher, Ronnie Reinhart and Robin Granites at the Warlpiri Media Association. Chris Ashby and Will Rogers, as well as Marina Alice, Alec Armstrong and Dale Nelson at PY Media. Clint Mitchell and George Henna at CAAMA and Greg McFarland and all the staff at Imparja. Melinda Hinkson for pointing me in the right direction and giving me sound advice on where to start. Jennifer Deger, Evan Wyatt, Philip Batty and Helen Molnar for sharing their experiences in Aboriginal broadcasting. Gertrude Stotz from the Pitjantjatjara Land Council for her knowledge of the Warlpiri and Toyotas. Nick Peterson for pointing out Marika Moisseeff's work. The National Indigenous Media Association, especially Gerry Pyne at the National Indigenous Radio Service. Nikki Page at 5UV for her insight into training. Mike Hollings at Te Mangai Paho for assistance in helping me to understand Maori broadcasting. Lisa Hill and Greg Harris at ATSIC for bringing me up-to-date with the latest in indigenous broadcasting policy. The helpful staff at the Australian Institute ofAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library. My supervisors Dr Elisabeth Patz and Dr Glen Lewis at the University of Canberra for keeping me on track. -

Preaud PHD Summary

This file is part of the following reference: Preaud, Martin (2009) Loi et culture en pays Aborigenes ; anthropologie des resaux autochtones du Kimberley, Nord- Ouest de l'Australie. PhD thesis, James Cook University Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/11819 Country, Law & Culture Anthropology of Indigenous Networks from the K i m b e r l e y A Thesis in anthropology submitted by MARTIN PRÉAUD March 2009 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Arts and Social Sciences James Cook University Supervisors: Dr Rosita Henry Dr Barbara Glowczewski 1 STATEMENT OF A C C E S S I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library and, via the Australian Digital Theses network, for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and; I do not wish to place any further restriction on access to this work. March 9th 2009 Signature Date 2 DECLARATIONS I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. I, the undersigned, the author of this work, declare that the electronic copy of this thesis provided to the James Cook University Library is an accurate copy of the print thesis submitted, within the limits of the technology available. -

A History of Regional Commercial Television Ownership and Control

Station Break: A History of Regional Commercial Television Ownership and Control Michael Thurlow B. Journalism This thesis is presented for the degree of Master of Research Macquarie University Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies 9 October 2015 This page has been left blank deliberately. Table of contents Abstract .................................................... i Statement of Candidate .................................... iii Acknowledgements ........................................... iv Abbreviations ............................................... v Figures ................................................... vii Tables ................................................... viii Introduction ................................................ 1 Chapter 1: New Toys for Old Friends ........................ 21 Chapter 2: Regulatory Foundations and Economic Imperatives . 35 Chapter 3: Corporate Ambitions and Political Directives .... 57 Chapter 4: Digital Protections and Technical Disruptions ... 85 Conclusion ................................................ 104 Appendix A: Stage Three Licence Grants .................... 111 Appendix B: Ownership Groups 1963 ......................... 113 Appendix C: Stage Four Licence Grants ..................... 114 Appendix D: Ownership Groups 1968 ......................... 116 Appendix E: Stage Six Licence Grants ...................... 117 Appendix F: Ownership Groups 1975 ......................... 118 Appendix G: Ownership Groups 1985 ......................... 119 Appendix H: -

~ ANNUAL REPORT AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL 1 January to 30 June 1977 Incorporating the 29Th Annual Report of the Austral

~ ~ ~ ANNUAL REPORT AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL 1 January to 30 June 1977 incorporating the 29th Annual Report of the _ Australian Broadcasting Control Board 1 July to 31 December 1976 S .. S . I) ELL t I PER.Sor.JAL Copy B~DADCPIST 'E.tJ&. PoST. ; 1" E: LEc_oM. 'Df-f'T Annual Report Australian Broadcasting Tribunal 1 January to 30 June 1977 incorporating the 29th Annual Report of the Australian Broadcasting Control Board 1 July to 31 December 1976 AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING SERVICE CANBERRA, 1978 © Commonwealth of Australia 1978 Printed by The Courier-Maif Printing Service, Campbell Street, Bowen Hills, Q. 4006. The Honourable the Minister for Post and Telecommunications In conformity with the provisions of Section 28 of the Broadcasting and Television Act 1942, I have pleasure in presenting the Twenty-Ninth Annual Report of the Australian Broadcasting Control Board for the period 1 July to 31 December 1976 and the Annual Report of the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal for the period I January to 30 June 1977. Bruce Gyngell Chairman 18 October 1977 iii CONTENTS page Part I: INTRODUCTION Legislation 1 Establishment of Tribunal · 2 Functions of the Tribunal 3 Meetings of the Board 3 Meetings of the Tribunal 4 Staff of the Tribunal 4 Location of Tribunal's Offices 5 Financial Accounts of Tribunal and Board 5 Part II: GENERAL Radio and Television Services in Operation since 1949 _ 6 Financial Results - Commercial Radio and Television 7 Stations Public Inquiry into Agreements under Section 88 of the 10 Broadcasting and Television