Revisiting Qumran Cave 1Q and Its Archaeological Assemblage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qumran Caves” in the Iron Age in the Light of the Pottery Evidence

CHAPTER 17 History of the “Qumran Caves” in the Iron Age in the Light of the Pottery Evidence Mariusz Burdajewicz Since the late ‘40s and the beginning of the ‘50s of the last Jerusalem carried out a survey of about 270 sites situated century, the north-eastern part of the Judean Desert has to the north and south of the Qumran site.4 Of the 40 sites been witnessing numerous archaeological surveys and (almost exclusively caves or cavities), where the traces of works (Table 17.1; Fig. 17.1). The main, but not the only one, human presence from various periods were found, only goal of various expeditions sent to the Dead Sea region, few of them yielded the finds pertaining to the Iron Age. was the quest for more and more scrolls. On this occasion, One large bowl and one lamp came from caves GQ 27 and apart from manuscripts, many other artefacts, like pottery GQ 39 respectively.5 Fragments of two vessels dated to the and the so-called small finds,1 have come to light. Their Iron Age II are mentioned as coming from cave GQ 13, and chronology range in date from the Chalcolithic to the a few pottery sherds, possibly dated to the same period, Arab periods. from cave GQ 6.6 The survey was completed in 1956, and The aim of this short paper is to present, on the basis of some additional pottery fragments from the Iron Age pottery evidence, some observations concerning the use were found in cave 11Q (fragments of jars, two lamps and of the caves during the Iron Age II–III. -

Worthy of Another Look: the Great Isaiah Scroll and the Book of Mormon

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 20 Number 2 Article 7 2011 Worthy of Another Look: The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Book of Mormon Donald W. Perry Stephen D. Ricks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Perry, Donald W. and Ricks, Stephen D. (2011) "Worthy of Another Look: The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Book of Mormon," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 20 : No. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol20/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Worthy of Another Look: The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Book of Mormon Author(s) Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks Reference Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 20/2 (2011): 78–80. ISSN 1948-7487 (print), 2167-7565 (online) Abstract Numerous differences exist between the Isaiah pas- sages in the Book of Mormon and the corresponding passages in the King James Version of the Bible. The Great Isaiah Scroll supports several of these differences found in the Book of Mormon. Five parallel passages in the Isaiah scroll, the Book of Mormon, and the King James Version of the Bible are compared to illus- trate the Book of Mormon’s agreement with the Isaiah scroll. WORTHY OF ANOTHER LOOK THE GREAT ISAIAH SCROLL AND THE BOOK OF MORMON DONALD W. -

History and Narrative in a Changing Society: James Henry Breasted and the Writing of Ancient Egyptian History in Early Twentieth Century America

History and Narrative in a Changing Society: James Henry Breasted and the Writing of Ancient Egyptian History in Early Twentieth Century America by Lindsay J. Ambridge A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Janet E. Richards, Chair Professor Carla M. Sinopoli Associate Professor Terry G. Wilfong Emily Teeter, Oriental Institute, University of Chicago © Lindsay J. Ambridge All rights reserved 2010 Acknowledgments The first person I would like to thank is my advisor and dissertation committee chair, Janet Richards, who has been my primary source of guidance from my first days at the University of Michigan. She has been relentlessly supportive not only of my intellectual interests, but also in securing fieldwork opportunities and funding throughout my graduate career. For the experiences I had over the course of four expeditions in Egypt, I am deeply grateful to her. Most importantly, she is always kind and unfailingly gracious. Terry Wilfong has been a consistent source of support, advice, and encyclopedic knowledge. His feedback, from my first year of graduate school to my last, has been invaluable. He is generous in giving advice, particularly on matters of language, style, and source material. It is not an overstatement to say that the completion of this dissertation was made possible by Janet and Terry’s combined resourcefulness and unflagging support. It is to Janet and Terry also that I owe the many opportunities I have had to teach at U of M. Working with them was always a pleasure. -

The Dead Sea Scrolls: a Biography Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS: A BIOGRAPHY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John J. Collins | 288 pages | 08 Nov 2012 | Princeton University Press | 9780691143675 | English | New Jersey, United States The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Biography PDF Book It presents the story of the scrolls from several perspectives - from the people of Qumran, from those second temple Israelites living in Jerusalem, from the early Christians, and what it means today. The historian Josephus relates the division of the Jews of the Second Temple period into three orders: the Sadducees , the Pharisees , and the Essenes. Currently, he is completing a comprehensive, multi-volume study on the archaeology of Qumran. DSSEL covers only the non-biblical Qumran texts based on a formal understanding of what constitutes a biblical text. Enter email address. And he unravels the impassioned disputes surrounding the scrolls and Christianity. The scrolls include the oldest biblical manuscripts ever found. Also recovered were archeological artifacts that confirmed the scroll dates suggested by paleographic study. His heirs sponsored construction of the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem's Israel Museum, in which these unique manuscripts are exhibited to the public. In the first of the Dead Sea Scroll discoveries was made near the site of Qumran, at the northern end of the Dead Sea. For example, the species of animal from which the scrolls were fashioned — sheep or cow — was identified by comparing sections of the mitochondrial DNA found in the cells of the parchment skin to that of more than 10 species of animals until a match was found. Noam Mizrahi from the department of biblical studies, in collaboration with Prof. -

Bible from Qumran Sidnie White Crawford

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sidnie White Crawford Publications Classics and Religious Studies 2014 The O" ther" Bible from Qumran Sidnie White Crawford Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/crawfordpubs This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sidnie White Crawford Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The "Other" Bible from Qumran by Sidnie White Crawford Where did the Bible come from? The Hebrew Bible, or Christian Old Testament, did not exist in the canonical form we know prior to the early second century C.E. Before that, certain books had become authoritative in the Jewish community, but the status of other books, which eventually did become part of the Hebrew Bible, was questionable. All Jews everywhere, since at least the fourth century B.C.E., accepted the authority of the Torah of Moses, the first five books of the Bible (also called the Pentateuch): Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Most Jews also accepted the books of the Prophets, including the Former Prophets or historical books (Joshua through Kings), as authoritative. The Samaritan community only accepted the Pentateuch as authoritative, and the Pentateuch remains their Bible today. Some parts of the Jewish community accepted the books found in the Writings as authoritative, but not all Jews accepted all of those books. The Jewish community that lived at Qumran and stored their manuscripts in the nearby caves, for example, do not seem to have accepted Esther as authoritative. -

Reassessing the Judean Desert Caves: Libraries, Archives, Genizas and Hiding Places

Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society 2007 Volume 25 Reassessing the Judean Desert Caves: Libraries, Archives, Genizas and Hiding Places STEPHEN PFANN In December 1952, five years after the discovery of Qumran cave 1, Roland de Vaux connected its manuscript remains to the nearby site of Khirbet Qumran when he found one of the unique cylindrical jars, typical of cave 1Q, embedded in the floor of the site. The power of this suggestion was such that, from that point on, as each successive Judean Desert cave containing first-century scrolls was discovered, they, too, were assumed to have originated from the site of Qumran. Even the scrolls discovered at Masada were thought to have arrived there by the hands of Essene refugees. Other researchers have since proposed that certain teachings within the scrolls of Qumran’s caves provide evidence for a sect that does not match that of the Essenes described by first-century writers such as Josephus, Philo and Pliny. These researchers prefer to call this group ‘the Qumran Community’, ‘the Covenanters’, ‘the Yahad ’ or simply ‘sectarians’. The problem is that no single title sufficiently covers the doctrines presented in the scrolls, primarily since there is a clear diversity in doctrine among these scrolls.1 In this article, I would like to present a challenge to this monolithic approach to the understanding of the caves and their scroll collections. This reassessment will be based on a close examination of the material culture of the caves (including ceramics and fabrics) and the palaeographic dating of the scroll collections in individual caves. -

The Dead Sea Scrolls

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 2000 The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints Donald W. Parry Stephen D. Ricks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Parry, Donald W. and Ricks, Stephen D., "The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints" (2000). Maxwell Institute Publications. 25. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Preface What is the Copper Scroll? Do the Dead Sea Scrolls contain lost books of the Bible? Did John the Baptist study with the people of Qumran? What is the Temple Scroll? What about DNA research and the scrolls? We have responded to scores of such questions on many occasions—while teaching graduate seminars and Hebrew courses at Brigham Young University, presenting papers at professional symposia, and speaking to various lay audiences. These settings are always positive experiences for us, particularly because they reveal that the general membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a deep interest in the scrolls and other writings from the ancient world. The nonbiblical Dead Sea Scrolls are of great import because they shed much light on the cultural, religious, and political position of some of the Jews who lived shortly before and during the time of Jesus Christ. -

University of Birmingham the Profile and Character of Qumran

University of Birmingham The Profile and Character of Qumran Cave 4 Hempel, Charlotte DOI: 10.1163/9789004316508_006 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Hempel, C 2016, The Profile and Character of Qumran Cave 4: The Community Rule Manuscripts as a Test Case. in M Fidanzio (ed.), The Caves of Qumran: Proceedings of the International Conference, Lugano 2014. STDJ, vol. 118, Brill, Leiden. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004316508_006 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Publisher conditions checked General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

BSBB9401 DEAD SEA SCROLLS Fall 2018 Dr. R. Dennis Cole NOBTS Mcfarland Chair of Archaeology Dodd Faculty 201 [email protected] 504-282-4455 X3248

BSBB9401 DEAD SEA SCROLLS Fall 2018 Dr. R. Dennis Cole NOBTS Mcfarland Chair of Archaeology Dodd Faculty 201 [email protected] 504-282-4455 x3248 NOBTS MISSION STATEMENT The mission of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary is to equip leaders to fulfill the Great Commission and the Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries. COURSE PURPOSE, CORE VALUE FOCUS, AND CURRICULUM COMPETENCIES New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary has five core values: Doctrinal Integrity, Spiritual Vitality, Mission Focus, Characteristic Excellence, and Servant Leadership. These values shape both the context and manner in which all curricula are taught, with “doctrinal integrity” and “characteristic academic excellence” being especially highlighted in this course. NOBTS has seven basic competencies guiding our degree programs. The student will develop skills in Biblical Exposition, Christian Theological Heritage, Disciple Making, Interpersonal Skills, Servant Leadership, Spiritual & Character Formation, and Worship Leadership. This course addresses primarily the compentency of “Biblical Exposition” competency by helping the student learn to interpret the Bible accurately through a better understanding of its historical and theological context. During the Academic Year 2018-19, the focal competency will be Doctrinal Integrity.. COURSE DESCRIPTION Research includes historical background and description of the Qumran cult and problems relating to the significance and dating of the Scrolls. Special emphasis is placed on a theological analysis of the non- biblical texts of the Dead Sea library on subjects such as God, man, and eschatology. Meaningful comparisons are sought in the Qumran view of sin, atonement, forgiveness, ethics, and messianic expectation with Jewish and Christian views of the Old and New Testaments as well as other Interbiblical literature. -

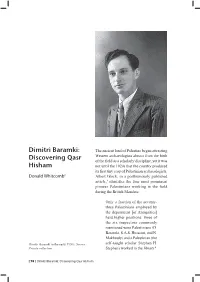

Dimitri Baramki: Discovering Qasr Hisham1

Dimitri Baramki: The ancient land of Palestine began attracting Western archaeologists almost from the birth Discovering Qasr of the field as a scholarly discipline, yet it was Hisham1 not until the 1920s that the country produced its first tiny crop of Palestinian archaeologists. Donald Whitcomb2 Albert Glock, in a posthumously published article,3 identifies the four most prominent pioneer Palestinians working in the field during the British Mandate: Only a fraction of the seventy- three Palestinians employed by the department [of Antiquities] held higher positions: three of the six inspectors commonly mentioned were Palestinians (D. Baramki, S.A.S. Husseini, and N. Makhouly) and a Palestinian (the Dimitri Baramki in the early 1930s. Source: self-taught scholar Stephan H. Private collection. Stephan) worked in the library.4 [ 78 ] Dimitri Baramki: Discovering Qasr Hisham Baramki and Husseini became colleagues again in Libya in the mid 1960s; Makhouly’s 1941 Guide to Acre, published by the Department of Antiquities, still turns up at sites like the sole Palestinian-owned hotel in Acre; and Stephan H. Stephan’s work continues to be cited today, as for example, in Mahmoud Hawari’s essay on the Citadel of Jerusalem in this publication. But it was Dimitri Baramki (1909-1984), frequently called the first Palestinian archaeologist, who was the most productive, and the only one who pursued a lifelong career in the field. He began as a student inspector of antiquities during the British Mandate two months short of his eighteenth birthday, and achieved an internationally acknowledged standing as a UNESCO expert, Professor of Archaeology and Curator of the Archaeological Museum at the American University of Beirut, and lecturer at the Lebanese University and the University of Balamand. -

The Qumran Collection As a Scribal Library Sidnie White Crawford

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sidnie White Crawford Publications Classics and Religious Studies 2016 The Qumran Collection as a Scribal Library Sidnie White Crawford Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/crawfordpubs This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sidnie White Crawford Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Qumran Collection as a Scribal Library Sidnie White Crawford Since the early days of Dead Sea Scrolls scholarship, the collection of scrolls found in the eleven caves in the vicinity of Qumran has been identified as a library.1 That term, however, was undefined in relation to its ancient context. In the Greco-Roman world the word “library” calls to mind the great libraries of the Hellenistic world, such as those at Alexandria and Pergamum.2 However, a more useful comparison can be drawn with the libraries unearthed in the ancient Near East, primarily in Mesopotamia but also in Egypt.3 These librar- ies, whether attached to temples or royal palaces or privately owned, were shaped by the scribal elite of their societies. Ancient Near Eastern scribes were the literati in a largely illiterate society, and were responsible for collecting, preserving, and transmitting to future generations the cultural heritage of their peoples. In the Qumran corpus, I will argue, we see these same interests of collection, preservation, and transmission. Thus I will demonstrate that, on the basis of these comparisons, the Qumran collection is best described as a library with an archival component, shaped by the interests of the elite scholar scribes who were responsible for it. -

The Dead Sea Scrolls: Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek Texts with English Translations

386 BOOK REVIEWS 65, n. 128:the wrongclause fromDaniel 7:9 is transcribed;it does not match the translationprovided. JohnC. Reeves WinthropUniversity RockHill, S.C. James H. Charlesworth, ed. The Dead Sea Scrolls: Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek Texts with English Translations. Vol. 1: Rule of the Community and RelatedDocuments. Princeton Theological Seminary Dead Sea Scrolls Project.Tubingen: J. C. B. Mohr(Paul Siebeck), and Louisville: Westminster JohnKnox Press, 1994. xxiii, 185 pp. The work under review is the first volume in a series designed to be "the first comprehensiveedition of texts, translations,and introductionsto all the Dead Sea Scrolls that are not copies of the [biblical]books" (p. xi). Accordingly,we are dealing with a massive project,especially since every fragment,no matterhow small in size, is to be includedin the series. Projectdirector James H. Charlesworthhas assembleda fine andwide array of scholars(the list of contributorsto the entireproject includes forty-five names)to assist him in this undertaking. Ten volumes are planned,as follows: (1) Rule of the Communityand Related Documents (i.e., the present volume); (2) Damascus Document, War Scroll, and Related Documents; (3) Damascus Document Fragments, More Precepts of the Torah, and Related Documents; (4) Angelic Liturgy, Prayers, and Psalms; (5) ThanksgivingHymns and Related Documents; (6) Targumon Job, Pesharim, and Related Documents; (7) Temple Scroll and Related Documents; (8) Genesis Apocryphon, New Jerusalem, and Related Documents; (9) Copper Scroll, Greek Fragments, and Miscellanea; and (10) Biblical Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha. The division of the texts into these volumesseems generallysound, but one mustquestion why the CairoGeniza text of the DamascusDocument (along with two fragments5Q12 and 6Q15) will appearin volume2, while the nine DamascusDocument fragments from Cave 4 will appearin volume 3 (this explicit informationis suppliedon p.