Physical Geology - 2Nd Edition 220

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4.5Making Metamorphic Rock Inferences

4.5 Making Metamorphic rock inferences How do geologists identify metamorphic rocks? Infer the parent rock Metamorphism (to change form) is a process in which a parent rock undergoes changes in the mineralogy, texture, and sometimes modifies the parent rocks chemical composition. Every metamorphic rock forms from a pre-existing rock, be it a metamorphic, igneous, or sedimentary rock, called the parent rock. Every metamorphic rock has a parent rock, called a “Protolith”. Source: Ohio Oil and Gas Energy Education Program 1. Pull out samples 4B, 13B, 17B, 19B, and 22B. These are all possible Protoliths “Parent Rocks” (sedimentary/ Igneous rocks) to a few of your metamorphic samples found in your kits. Keep these out in front of you. 2. Pull out rock samples 23B, 28B, 29B, and 30B. These are all metamorphic rocks that have undergone metamorphism. Lay the rocks out on the table in front of you. 3. Using dilute hydrochloric acid (HCl) or vinegar put a drop on sample 29B; it should effervesce or “fizz”. That means that the Protolith “parent rock” you choose should also effervesce or “fizz”. If it doesn’t then you will need to go back and try again until you find the correct Protolith. 4. Match the metamorphic rock with its Protolith “parent rock” below: Metamorphic 23B 27B 28B 29B 30B rock Protolith “Parent rock” Reflection Name two primary environmental changes a protolith rock must undergo to transition from its protolith to a metamorphic rock. OHIO OIL & GAS ENERGY EDUCATION PROGRAM oogeep.org 4.5 Making metamorphic rock inferences continued Infer the grade Sometimes the protoliths “parent rocks” are a metamorphic rock and that parent rock is metamorphosed into a new metamorphic rock that has experienced a different grade (intensity) of metamorphism. -

The Geology of the Tama Kosi and Rolwaling Valley Region, East-Central Nepal

The geology of the Tama Kosi and Rolwaling valley region, East-Central Nepal Kyle P. Larson* Department of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, 114 Science Place, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 5E2, Canada ABSTRACT Tama Kosi valley in east-central Nepal (Fig. 1). which were in turn assigned to either the Hima- In order to properly evaluate the evolution of the layan gneiss group or the Midlands metasedi- The Tama Kosi/Rolwaling area of east- Himalaya and understand the processes respon- ment group (Fig. 2). The units of Ishida (1969) central Nepal is underlain by the exhumed sible for its formation, it is critical that all areas and Ishida and Ohta (1973) are quite similar in mid-crustal core of the Himalaya. The geol- along the length of the mountain chain be inves- description to the tectonostratigraphy reported ogy of the area consists of Greater Hima- tigated, at least at a reconnaissance scale. by Schelling (1992) who revisited and expanded layan sequence phyllitic schist, paragneiss, The Tama Kosi valley is situated between the the scope of their early reconnaissance work. and orthogneiss that generally increase in Cho Oyu/Everest/Makalu massifs to the east Schelling (1992) separated the geology of metamorphic grade from biotite ± garnet and the Kathmandu klippe/nappe to the west the lower and middle portion of the Tama Kosi assemblages to sillimanite-grade migmatite (Fig. 1). Recent work in these areas serves to into the more traditional Greater Himalayan up structural section. All metamorphic rocks highlight stark differences between them. In the sequence (Higher Himalayan Crystallines) and are pervasively deformed and commonly Kathmandu region, the extruded midcrustal core Lesser Himalayan sequence lithotectonic assem- record top-to-the-south sense shear. -

Metamorphic Rocks.Pdf

Metamorphism & Metamorphic Rocks (((adapted from Brunkel, 2012) Metamorphic Rocks . Changed rocks- with heat and pressure . But not melted . Change in the solid state . Textural changes (always) . Mineralogy changes (usually) Metamorphism . The mineral changes that transform a parent rock to into a new metamorphic rock by exposure to heat, stress, and fluids unlike those in which the parent rock formed. granite gneiss Geothermal gradient Types of Metamorphism . Contact metamorphism – – Happens in wall rock next to intrusions – HEAT is main metamorphic agent . Contact metamorphism Contact Metamorphism . Local- Usually a zone only a few meters wide . Heat from plutons intruded into “cooler” country rock . Usually forms nonfoliated rocks Types of Metamorphism . Hydrothermal metamorphism – – Happens along fracture conduits – HOT FLUIDS are main metamorphic agent Types of Metamorphism . Regional metamorphism – – Happens during mountain building – Most significant type – STRESS associated with plate convergence & – HEAT associated with burial (geothermal gradient) are main metamorphic agents . Contact metamorphism . Hydrothermal metamorphism . Regional metamorphism . Wide range of pressure and temperature conditions across a large area regional hot springs hydrothermal contact . Regional metamorphism Other types of Metamorphism . Burial . Fault zones . Impact metamorphism Tektites Metamorphism and Plate Tectonics . Fault zone metamorphism . Mélange- chaotic mixture of materials that have been crumpled together Stress (pressure) . From burial -

Basic Aggregate Properties Section 1

Basic Aggregate Properties Section 1: Introduction 1 Aggregate Types Aggregates are divided into 3 categories based on particle size: • Coarse Aggregate Gravel or crushed stone Particle sizes larger than No. 4 sieve (4.75mm) • Fine Aggregate Sand or washed screenings Particle sizes between No. 4 and No. 200 sieve (4.75mm-75µm) •Fines Silt or clay Particle sizes smaller than No. 200 sieve (75µm) Coarse Aggregate Coarse Aggregate can come from several sources. Each of these sources can produce satisfactory aggregates depending on the intended use. Each parent material has advantages and disadvantages associated with it. 2 Coarse Aggregate Natural gravel Crushed stone Lightweight aggregate Recycled and waste products •slag • rubble •mine waste • asphalt and concrete pavement Important Properties of Aggregate All of these properties can have an affect on how the aggregate performs the tasks that are expected of it. •Shape • Surface texture •Gradation • Specific gravity • Absorption •Hardness • Soundness •Strength • Deleterious materials 3 The ideal aggregate is… Strong and hard to resist loads applied Chemically inert so it is not broken down by reactions with substances it comes in contact with Has a stable volume so that it does not shrink or swell Bonds tightly with asphalt and portland cement paste The ideal aggregate… Contains no impurities or weak particles Would be the perfect size and gradation for the application intended Would be locally available and economical 4 Aggregate in Practice There is a wide range in strength and hardness even among aggregates produced from the same type of parent material. Particles have pores that affect their absorption properties and how well they bond with asphalt and Portland cement. -

Geologic Map of the Loudoun County, Virginia, Part of the Harpers Ferry Quadrangle

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP MF-2173 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE LOUDOUN COUNTY, VIRGINIA, PART OF THE HARPERS FERRY QUADRANGLE By C. Scott Southworth INTRODUCTION Antietam Quartzite constituted the Chilhowee Group of Early Cambrian age. Bedrock and surficial deposits were mapped in 1989-90 as part For this report, the Loudoun Formation is not recognized. As of a cooperative agreement with the Loudoun County Department used by Nickelsen (1956), the Loudoun consisted primarily of of Environmental Resources. This map is one of a series of geologic phyllite and a local uppermost coarse pebble conglomerate. Phyl- field investigations (Southworth, 1990; Jacobson and others, lite, of probable tuffaceous origin, is largely indistinguishable in the 1990) in Loudoun County, Va. This report, which includes Swift Run, Catoctin, and Loudoun Formations. Phyl'ite, previously geochemical and structural data, provides a framework for future mapped as Loudoun Formation, cannot be reliably separated from derivative studies such as soil and ground-water analyses, which phyllite in the Catoctin; thus it is here mapped as Catoctin are important because of the increasing demand for water and Formation. The coarse pebble conglomerate previously included in because of potential contamination problems resulting from the the Loudoun is here mapped as a basal unit of the overlying lower recent change in land use from rural-agricultural to high-density member of the Weverton Formation. The contact of the conglom suburban development. erate and the phyllite is sharp and is interpreted to represent a Mapping was done on 5-ft-contour interval topographic maps major change in depositional environment. -

Dec 15, 1999 LAB MANUAL 1209

October 2012 LAB MANUAL 1209.0 1209.0 LITHOLOGICAL SUMMARY 1209.1 GENERAL This test procedure is performed on aggregates to determine the per- centage of various rock types (especially the deleterious varieties) regulated in the Standard Specifications for Construction. 1209.2 APPARATUS A. Dilute Hydrochloric Acid (10% ±) - One part concentrated HCL with 9 parts water and eyedropper applicator B. "Brass Pencil" - (See Section 1218.2 for description) C. Balances - Shall conform to AASHTO M 231 (Classes G2 & G5). Readability & sensitivity 0.1 grams, accuracy 0.1 grams or 0.1%. Balances shall be appropriate for the specific use. D. Small Hammer, Steel Plate and Safety Glasses E. Paper Containers - Approximately 75mm (3") in diameter F. Magnifying Hand Lens (10 to 15 power) G. Unglazed Porcelain Tile (streak plate) 1209.3 TEST SAMPLE The test sample, prepared in accordance with Section 1201.4G, shall be washed (Observe washing restrictions in Section 1201.4G1c) and then dried to a constant weight at a temperature of 110 ± 5 °C (230 ± 9 °F). (See Section 1201, Table 1, for sample weights.) 1209.4 PROCEDURE Examine and classify each rock piece individually. Some rock types may need to be cracked open to identify or determine the identifying properties of the rock. (Always wear safety glasses). The following general guidelines are for informational purposes: • Always break open pieces of soft rock or any others of which you are unsure as the outside is often weathered. • Pick the easy particles first October 2012 LAB MANUAL 1209.4 • Don't be overly concerned about questionable particles unless they will fail the sample. -

Catoctin Formation

Glimpses of the Past: THE GEOLOGY of VIRGINIA The Catoctin Formation — Virginia is for Lavas Alex Johnson and Chuck Bailey, Department of Geology, College of William & Mary Stony Man is a high peak in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains that tops out at just over 1200 m (4,000’). Drive south from Thornton Gap along the Skyline Drive and you’ll see the impressive cliffs of Stony Man’s northwestern face. These are the cliffs that give the mountain its name, as the cliffs and slopes have a vague resemblance to a reclining man’s forehead, eye, nose, and beard. Climb to the top and you’ll see peculiar bluish-green rocks exposed on the summit that are ancient lava flows, part of a geologic unit known as the Catoctin Formation. From the presidential retreat at Camp David to Jefferson’s Monticello, from Harpers Ferry to Humpback Rocks, the Catoctin Formation underlies much of the Blue Ridge. This distinctive geologic unit tells us much about the long geologic history of the Blue Ridge and central Appalachians. Stony Man’s summit and northwestern slope, Shenandoah National Park, Virginia. Cliffs expose metabasaltic greenstone of the Neoproterozoic Catoctin Formation. (CMB photo). Geologic cross section of Stony Man summit area (modified from Badger, 1999). The Catoctin Formation was first named by Arthur Keith in 1894 and takes its name for exposures on Catoctin Mountain, a long ridge that stretches from Maryland into northern Virginia. The word Catoctin is rooted in the old Algonquin term Kittockton. The exact meaning of the term has become a point of contention; among historians the translation “speckled mountain” is preferred, however local tradition holds that that Catoctin means “place of many deer” (Kenny, 1984). -

Oregon Geologic Digital Compilation Rules for Lithology Merge Information Entry

State of Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries Vicki S. McConnell, State Geologist OREGON GEOLOGIC DIGITAL COMPILATION RULES FOR LITHOLOGY MERGE INFORMATION ENTRY G E O L O G Y F A N O D T N M I E N M E T R R A A L P I E N D D U N S O T G R E I R E S O 1937 2006 Revisions: Feburary 2, 2005 January 1, 2006 NOTICE The Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries is publishing this paper because the infor- mation furthers the mission of the Department. To facilitate timely distribution of the information, this report is published as received from the authors and has not been edited to our usual standards. Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries Oregon Geologic Digital Compilation Published in conformance with ORS 516.030 For copies of this publication or other information about Oregon’s geology and natural resources, contact: Nature of the Northwest Information Center 800 NE Oregon Street #5 Portland, Oregon 97232 (971) 673-1555 http://www.naturenw.org Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries - Oregon Geologic Digital Compilation i RULES FOR LITHOLOGY MERGE INFORMATION ENTRY The lithology merge unit contains 5 parts, separated by periods: Major characteristic.Lithology.Layering.Crystals/Grains.Engineering Lithology Merge Unit label (Lith_Mrg_U field in GIS polygon file): major_characteristic.LITHOLOGY.Layering.Crystals/Grains.Engineering major characteristic - lower case, places the unit into a general category .LITHOLOGY - in upper case, generally the compositional/common chemical lithologic name(s) -

A Systematic Nomenclature for Metamorphic Rocks

A systematic nomenclature for metamorphic rocks: 1. HOW TO NAME A METAMORPHIC ROCK Recommendations by the IUGS Subcommission on the Systematics of Metamorphic Rocks: Web version 1/4/04. Rolf Schmid1, Douglas Fettes2, Ben Harte3, Eleutheria Davis4, Jacqueline Desmons5, Hans- Joachim Meyer-Marsilius† and Jaakko Siivola6 1 Institut für Mineralogie und Petrographie, ETH-Centre, CH-8092, Zürich, Switzerland, [email protected] 2 British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, [email protected] 3 Grant Institute of Geology, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, [email protected] 4 Patission 339A, 11144 Athens, Greece 5 3, rue de Houdemont 54500, Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy, France, [email protected] 6 Tasakalliontie 12c, 02760 Espoo, Finland ABSTRACT The usage of some common terms in metamorphic petrology has developed differently in different countries and a range of specialised rock names have been applied locally. The Subcommission on the Systematics of Metamorphic Rocks (SCMR) aims to provide systematic schemes for terminology and rock definitions that are widely acceptable and suitable for international use. This first paper explains the basic classification scheme for common metamorphic rocks proposed by the SCMR, and lays out the general principles which were used by the SCMR when defining terms for metamorphic rocks, their features, conditions of formation and processes. Subsequent papers discuss and present more detailed terminology for particular metamorphic rock groups and processes. The SCMR recognises the very wide usage of some rock names (for example, amphibolite, marble, hornfels) and the existence of many name sets related to specific types of metamorphism (for example, high P/T rocks, migmatites, impactites). -

Metamorphic Rocks

Metamorphic Rocks Geology 200 Geology for Environmental Scientists Regionally metamorphosed rocks shot through with migmatite dikes. Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Colorado Metamorphic rocks from Greenland, 3.8 Ga (billion years old) Major Concepts • Metamorphic rocks can be formed from any rock type: igneous, sedimentary, or existing metamorphic rocks. • Involves recrystallization in the solid state, often with little change in overall chemical composition. • Driving forces are changes in temperature, pressure, and pore fluids. • New minerals and new textures are formed. Major Concepts • During metamorphism platy minerals grow in the direction of least stress producing foliation. • Rocks with only one, non-platy, mineral produce nonfoliated rocks such as quartzite or marble. • Two types of metamorphism: contact and regional. Metamorphism of a Granite to a Gneiss Asbestos, a metamorphic amphibole mineral. The fibrous crystals grow parallel to least stress. Two major types of metamorphism -- contact and regional Major Concepts • Foliated rocks - slate, phyllite, schist, gneiss, mylonite • Non-foliated rocks - quartzite, marble, hornfels, greenstone, granulite • Mineral zones are used to recognize metamorphic facies produced by systematic pressure and temperature changes. Origin of Metamorphic Rocks • Below 200oC rocks remain unchanged. • As temperature rises, crystal lattices are broken down and reformed with different combinations of atoms. New minerals are formed. • The mineral composition of a rock provides a key to the temperature of formation (Fig. 6.5) Fig. 6.5. Different minerals of the same composition, Al2SiO5, are stable at different temperatures and pressures. Where does the heat come from? • Hot magma ranges from 700-12000C. Causes contact metamorphism. • Deep burial - temperature increases 15-300C for every kilometer of depth in the crust. -

Chapter 22: Classification of Metamorphic Rocks

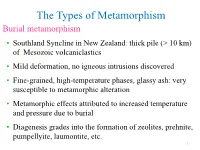

The Types of Metamorphism Burial metamorphism • Southland Syncline in New Zealand: thick pile (> 10 km) of Mesozoic volcaniclastics • Mild deformation, no igneous intrusions discovered • Fine-grained, high-temperature phases, glassy ash: very susceptible to metamorphic alteration • Metamorphic effects attributed to increased temperature and pressure due to burial • Diagenesis grades into the formation of zeolites, prehnite, pumpellyite, laumontite, etc. 1 The Types of Metamorphism Burial metamorphism occurs in areas that have not experienced significant deformation or orogeny • Restricted to large, relatively undisturbed sedimentary piles away from active plate margins . The Gulf of Mexico? . Bengal Fan? 2 The Types of Metamorphism Burial metamorphism occurs in areas that have not experienced significant deformation or orogeny • Bengal Fan → sedimentary pile > 22 km • Extrapolate → 250-300oC at the base (P ~ 0.6 GPa) • Passive margins often become active • Areas of burial metamorphism may thus become areas of orogenic metamorphism 3 The Types of Metamorphism Hydrothermal metamorphism • Hot H2O-rich fluids • Usually involves metasomatism • Difficult type to constrain: hydrothermal effects often play some role in most of the other types of metamorphism 4 The Types of Metamorphism Ocean-Floor Metamorphism affects the oceanic crust at ocean ridge spreading centers • Considerable metasomatic alteration, notably loss of Ca and Si and gain of Mg and Na • Highly altered chlorite-quartz rocks- distinctive high-Mg, low-Ca composition • Exchange between basalt and hot seawater • Another example of hydrothermal metamorphism 5 The Types of Metamorphism Fault-Zone and Impact Metamorphism High rates of deformation and strain with only minor recrystallization Impact metamorphism at meteorite (or other bolide) impact craters Both correlate with dynamic metamorphism 6 (a) Shallow fault zone with fault breccia (b) Slightly deeper fault zone (exposed by erosion) with some ductile flow and fault mylonite Figure 21.7. -

Topic Xi Formation of Rocks

UNIT H MINERALS AND ROCKS ROCKS ARE MADE UP OF MINERALS MINERAL - NATURALLY OCCURRING, INORGANIC, CRYSTALLINE SUBSTANCE WITH CHARACTERISTIC PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL PROPERTIES. ROCK FORMING MINERALS FELDSPAR, QUARTZ, MICA, CALCITE, HORNBLENDE, AUGITE, GARNET, MAGNETITE, OLIVINE, PYRITE AND TALC. THESE MINERALS MAKE UP MORE THAN 90% OF THE ROCKS IN THE LITHOSPHERE IDENTIFYING MINERALS physical properties are determined by the internal arrangement of atoms MINERALS ARE CLASSIFIED BY THE FOLLOWING PHYSICAL PROPERTIES: COLOR STREAK LUSTER HARDNESS SPECIFIC GRAVITY FRACTURE/CLEAVAGE Luster Metallic- looks like shiny metal Non-metallic- all the other ways that a mineral can shine Glassy/vitreous- shines like a piece of broken glass (most common non-metallic) Dull/earthy- no shine at all Resinous/waxy- looks like a piece of plastic or dried glue Pearly- looks oily it may have a slight rainbow like an oil slick on water. Hardness Fingernail 2.5 Penny 3.5 Iron Nail 4.5 Glass Plate 5.5 Steel File 6.5 MOH’S SCALE OF HARDNESS 1-TALC FINGERNAIL SCRATCHES EASILY 2-GYPSUM FINGERNAIL SCRATCHES 3-CALCITE COPPER PENNY SCRATCHES 4-FLUORITE STEEL FILE SCRATCHES EASILY 5-APATITE STEEL FILE SCRATCHES 6-FELDSPAR SCRATCHES WINDOW GLASS 7-QUARTZ HARDEST COMMON MINERAL; SCRATCHES GLASS EASILY 8-TOPAZ HARDER THAN ANY COMMON MINERAL 9-CORUNDUM SCRATCHES TOPAZ 10- DIAMOND HARDEST OF ALL MINERALS MINERAL FAMILIES SILICATES - MADE OF SILICON AND OXYGEN ABOUT 60% OF ALL MINERALS ARE SILICATES THE SILICON - OXYGEN TETRAHEDRON - ONE SILICON ATOM AND 4 OXYGEN ATOMS. A VERY STRONG STRUCTURE SILICATE FAMILY OLIVINE ISOLATED TETRAHEDRA GREENISH COLOR, NO CLEAVAGE PLANES ASBESTOS CHAIN TETRAHEDRA FIBERLIKE MICA SHEET TETRAHEDRA QUARTZ NETWORK TETRAHEDRA ALL SILICON-OXYGEN TETRAHEDRA CARBONATE MINERALS CARBON ATOM IN COMBINATION WITH 3 OXYGEN ATOMS CALCITE IRON OXIDES AND SULFIDES AN OXIDE IS A MINERAL CONSISTING OF A METAL ELEMENT COMBINED WITH OXYGEN.