Community Radio News Audiences and Political Change in Jordan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice Journal

JUSTICE JOURNAL The JUSTICE Journal aims to promote debate on topical issues relating to human rights and the rule of law. It focuses on JUSTICE’s core areas of expertise and concern: • human rights • criminal justice • equality • EU justice and home affairs • the rule of law • access to justice www.justice.org.uk Section head JUSTICE – advancing justice, human rights and the rule of law JUSTICE is an independent law reform and human rights organisation. It works largely through policy- orientated research; interventions in court proceedings; education and training; briefings, lobbying and policy advice. It is the British section of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ). The JUSTICE Journal editorial advisory board: Philip Havers QC, One Crown Office Row Barbara Hewson, Hardwicke Civil Professor Carol Harlow, London School of Economics Anthony Edwards, TV Edwards JUSTICE, 59 Carter Lane, London EC4V 5AQ Tel: +44 (0)20 7329 5100 Fax: +44 (0)20 7329 5055 E-mail: [email protected] www.justice.org.uk © JUSTICE 2006 ISSN 1743-2472 Designed by Adkins Design Printed by Hobbs the Printers Ltd, Southampton C o n t e n t s JUSTICE Journal ContentsTitle title Editorial WritingAuthor it down name 4 Roger Smith Papers Five years on from 9/11 – time to reassert the rule of law 8 Mary Robinson Politics and the law: constitutional balance or institutional confusion? 18 Jeffrey Jowell QC Lifting the ban on intercept evidence in terrorism cases 34 Eric Metcalfe Articles Parliamentary scrutiny: an assessment of the work of the constitutional 62 -

Broadcasting Ii Aug 5

The Fifth Estate R A D I O T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E S A T E L L I T E Broadcasting ii Aug 5 WE'RE PROUD TO BE VOTED THE TWIN CITIES' #1 MUSIC STATION FOR 7 YEARS IN A ROW.* And now, VIKINGS Football! Exciting play -by-play with Joe McConnell and Stu Voigt, plus Bud Grant 4 times a week. Buy a network of 55 stations. Contact Tim Monahan at 612/642 -4141 or Christal Radio for details AIWAYS 95 AND SUNNY.° 'Art:ron 1Y+ Metro Shares 6A/12M, Mon /Sun, 1979-1985 K57P-FM, A SUBSIDIARY OF HUBBARD BROADCASTING. INC. I984 SUhT OGlf ZZ T s S-lnd st-'/AON )IMM 49£21 Z IT 9.c_. I Have a Dream ... Dr. Martin Luther KingJr On January 15, 1986 Dr. King's birthday becomes a National Holiday KING... MONTGOMERY For more information contact: LEGACY OF A DREAM a Fox /Lorber Representative hour) MEMPHIS (Two Hours) (One-half TO Written produced and directed Produced by Ely Landau and Kaplan. First Richard Kaplan. Nominated for MFOXILORBER by Richrd at the Americ Film Festival. Narrated Academy Award. Introduced by by Jones. Harry Belafonte. JamcsEarl "Perhaps the most important film FOX /LORBER Associates, Inc. "This is a powerful film, a stirring documentary ever made" 432 Park Avenue South film. se who view it cannot Philadelphia Bulletin New York, N.Y. 10016 fail to be moved." Film News Telephone: (212) 686 -6777 Presented by The Dr.Martin Luther KingJr.Foundation in association with Richard Kaplan Productions. -

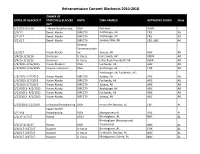

Retrans Blackouts 2010-2018

Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 OWNER OF DATES OF BLACKOUT STATION(S) BLACKED MVPD DMA NAME(S) NETWORKS DOWN State OUT 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH National WGN - 2/3/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV Juneau-Stika, AK CBS, NBC AK General CoMMunication 12/5/17 Vision Alaska Inc. Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Fort SMitH, AK KXUN AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AK KLRA AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Vision Alaska II DISH Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Coastal Television DISH AncHorage, AK FOX AK AncHorage, AK; Fairbanks, AK; 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV AncHorage, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/23/2018-2/2/2018 Lockwood Broadcasting DISH Huntsville-Decatur, AL CW AL SagaMoreHill 5/22/18 Broadcasting DISH MontgoMery AL ABC AL 1/1/17-1/7/17 Hearst AT&T BirMingHaM, AL NBC AL BirMingHaM (Anniston and 3/3/17-4/26/17 Hearst DISH Tuscaloosa) NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse BirMingHaM, AL FOX AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse Huntsville-Decatur, AL NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse MontgoMery-SelMa, AL NBC AL Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH -

Report on Future Funding of Public Service Broadcasting

Tithe an Oireachtais An Comhchoiste um Chumarsáid, Gníomhú ar son na hAeráide agus Comhshaol Tuarascáil ón gComhchoiste maidir leis Craoltóireacht Seirbhíse Poiblí a Mhaoiniú sa Todhchaí A leagadh faoi bhráid dhá Theach an Oireachtais 28 Samhain 2017 Houses of the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Communications, Climate Action and Environment Report of the Joint Committee on the Future Funding of Public Service Broadcasting Laid before both Houses of the Oireachtas 28 November 2017 32CCAE002 Tithe an Oireachtais An Comhchoiste um Chumarsáid, Gníomhú ar son na hAeráide agus Comhshaol Tuarascáil ón gComhchoiste maidir leis Craoltóireacht Seirbhíse Poiblí a Mhaoiniú sa Todhchaí A leagadh faoi bhráid dhá Theach an Oireachtais 28 Samhain 2017 Houses of the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Communications, Climate Action and Environment Report of the Joint Committee on the Future Funding of Public Service Broadcasting Laid before both Houses of the Oireachtas 28 November 2017 32CCAE002 Report on Future Funding of Public Service Broadcasting TABLE OF CONTENTS Brollach .............................................................................................................. 3 Preface ............................................................................................................... 4 1. Key Issue: The Funding Model – Short Term Solutions .......................... 6 Recommendation 1 - Fairness and Equity ............................................................ 6 Recommendation 2 – All Media Consumed ........................................................... -

Jordan Rule of Law and Anti-Corruption Assessment

JORDAN RULE OF LAW AND ANTI-CORRUPTION ASSESSMENT Prepared under Task Order, AID-278-TO-13-00001 under the Democracy and Governance Analytical Ser- vices Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-10-00004. Submitted to: USAID/Jordan Prepared by: Charles Costello Rick Gold Keith Henderson Contractor: Democracy International, Inc. 7600 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 1010 Bethesda, MD 20814 Tel: 301.961.1660 Email: [email protected] JORDAN RULE OF LAW AND ANTI-CORRUPTION ASSESS- MENT June 2013 The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 BACKGROUND .................................................................................... 2 PART I: RULE OF LAW ....................................................................... 5 PART II: ANTI-CORRUPTION ......................................................... 24 FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................... 46 ANNEX A: PRIORITIZED RECOMMENDED ACTIVITIES......... A-1 ANNEX B: SCOPE OF WORK ........................................................ B-1 ANNEX C: BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................... C-1 ANNEX D: LIST OF INTERVIEWEES ........................................... D-1 ACRONYMS ABA American Bar Association ACC Anti-Corruption Commission CC Constitutional Court Convention to Eliminate All -

Shortwave-Listener's

skï.. Radio lhaek TWO DOLLARS AND TWENTY—FIVE CENTS 62-2032 Shortwave Listener's Guide by H. Charles Woodruff Howard W. Sams & Co., Inc. 4300 WEST 62ND ST. INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA 46268 USA Copyright 0 1964, 1966, 1968, 1970, 1973, 1976, and 1980 by Howard W. Sams & Co., Inc. Indianapolis, Indiana 46268 EIGHTH EDITION FIRST PRINTING-1980 All rights reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. No patent liability is assumed with respect to the use of the information contained herein. While every pre- caution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions. Neither is any liability assumed for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. International Standard Book Number: 0-672-21655-8 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79-67132 Printed in the United States of America. Preface Every owner of a shortwave receiving set is familiar with the thrill that comes from hearing a distant station broadcasting from a foreign country. To hundreds of thousands of people the world over, short- wave listening (often referred to as swl) represents the most satisfy- ing, the most worthwhile of all hobbies. It has been estimated that more than 25 million shortwave receivers are in the hands of the American public, with the number increasing daily. To explore the international shortwave broadcasting bands in a knowledgeable manner, the shortwave listener must have available a list of shortwave stations, their frequencies, and their times of trans- mission. -

CV – June 2021 – 1

SÉVERINE AUTESSERRE * Department of Political Science. 3009 Broadway. New York, NY 10027-6598 ( (1) (212) 854-4877 : [email protected] / http://www.severineautesserre.com CURRENT POSITION: Professor, Department of Political Science, Barnard College, Columbia University, July 2007 - Present Assistant Professor from 2007 to 2015; promoted to Associate Professor with tenure in 2015 and to Professor in 2017; elected Department Chair (2022 - 2025) Research civil and international wars, international interventions, and African politics, and disseminate research findings through seminars, conferences, and scientific articles Main field research site: Democratic Republic of Congo. Other sites: Burundi, Cyprus, Colombia, Israel-Palestine, Northern Ireland, South Sudan, Timor-Leste, Somaliland Teach undergraduate and graduate classes on international relations and African politics Hold a courtesy appointment (since 2009) and a senior research scholar position (since 2015) at the School of International and Public Affairs Affiliated with the Columbia University Saltzman Institute for War and Peace Studies, Columbia University Institute for African Studies, Columbia University Institute for the Study of Human Rights, and Barnard College Africana Studies Program PUBLICATIONS Books The Frontlines of Peace: An Insider’s Guide to Changing the World. • Hardback & eBook: Oxford University Press, 2021 Audiobook: Audible, 2021 • Reviewed to date in: Diplomatie, The Financial Times, Foreign Affairs, International Peacekeeping, Política Exterior, The Economist, -

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1)

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1) Full Full Full Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation 2 Los Angeles, CA KTLA The CW 57 Mobile, AL WKRG CBS 111 Springfield, MA WWLP NBC 3 Chicago, IL WGN Independent WFNA The CW 112 Lansing, MI WLAJ ABC 4 Philadelphia, PA WPHL MNTV 59 Albany, NY WTEN ABC WLNS CBS 5 Dallas, TX KDAF The CW WXXA FOX 113 Sioux Falls, SD KELO CBS 6 San Francisco, CA KRON MNTV 60 Wilkes Barre, PA WBRE NBC KDLO CBS 7 DC/Hagerstown, WDVM(2) Independent WYOU CBS KPLO CBS MD WDCW The CW 61 Knoxville, TN WATE ABC 114 Tyler-Longview, TX KETK NBC 8 Houston, TX KIAH The CW 62 Little Rock, AR KARK NBC KFXK FOX 12 Tampa, FL WFLA NBC KARZ MNTV 115 Youngstown, OH WYTV ABC WTTA MNTV KLRT FOX WKBN CBS 13 Seattle, WA KCPQ(3) FOX KASN The CW 120 Peoria, IL WMBD CBS KZJO MNTV 63 Dayton, OH WDTN NBC WYZZ FOX 17 Denver, CO KDVR FOX WBDT The CW 123 Lafayette, LA KLFY CBS KWGN The CW 66 Honolulu, HI KHON FOX 125 Bakersfield, CA KGET NBC KFCT FOX KHAW FOX 129 La Crosse, WI WLAX FOX 19 Cleveland, OH WJW FOX KAII FOX WEUX FOX 20 Sacramento, CA KTXL FOX KGMD MNTV 130 Columbus, GA WRBL CBS 22 Portland, OR KOIN CBS KGMV MNTV 132 Amarillo, TX KAMR NBC KRCW The CW KHII MNTV KCIT FOX 23 St. Louis, MO KPLR The CW 67 Green Bay, WI WFRV CBS 138 Rockford, IL WQRF FOX KTVI FOX 68 Des Moines, IA WHO NBC WTVO ABC 25 Indianapolis, IN WTTV CBS 69 Roanoke, VA WFXR FOX 140 Monroe, AR KARD FOX WTTK CBS WWCW The CW WXIN FOX KTVE NBC 72 Wichita, KS -

VAB Member Stations

2018 VAB Member Stations Call Letters Company City WABN-AM Appalachian Radio Group Bristol WACL-FM IHeart Media Inc. Harrisonburg WAEZ-FM Bristol Broadcasting Company Inc. Bristol WAFX-FM Saga Communications Chesapeake WAHU-TV Charlottesville Newsplex (Gray Television) Charlottesville WAKG-FM Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation Danville WAVA-FM Salem Communications Arlington WAVY-TV LIN Television Portsmouth WAXM-FM Valley Broadcasting & Communications Inc. Norton WAZR-FM IHeart Media Inc. Harrisonburg WBBC-FM Denbar Communications Inc. Blackstone WBNN-FM WKGM, Inc. Dillwyn WBOP-FM VOX Communications Group LLC Harrisonburg WBRA-TV Blue Ridge PBS Roanoke WBRG-AM/FM Tri-County Broadcasting Inc. Lynchburg WBRW-FM Cumulus Media Inc. Radford WBTJ-FM iHeart Media Richmond WBTK-AM Mount Rich Media, LLC Henrico WBTM-AM Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation Danville WCAV-TV Charlottesville Newsplex (Gray Television) Charlottesville WCDX-FM Urban 1 Inc. Richmond WCHV-AM Monticello Media Charlottesville WCNR-FM Charlottesville Radio Group (Saga Comm.) Charlottesville WCVA-AM Piedmont Communications Orange WCVE-FM Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCVE-TV Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCVW-TV Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCYB-TV / CW4 Appalachian Broadcasting Corporation Bristol WCYK-FM Monticello Media Charlottesville WDBJ-TV WDBJ Television Inc. Roanoke WDIC-AM/FM Dickenson Country Broadcasting Corp. Clintwood WEHC-FM Emory & Henry College Emory WEMC-FM WMRA-FM Harrisonburg WEMT-TV Appalachian Broadcasting Corporation Bristol WEQP-FM Equip FM Lynchburg WESR-AM/FM Eastern Shore Radio Inc. Onley 1 WFAX-AM Newcomb Broadcasting Corporation Falls Church WFIR-AM Wheeler Broadcasting Roanoke WFLO-AM/FM Colonial Broadcasting Company Inc. Farmville WFLS-FM Alpha Media Fredericksburg WFNR-AM/FM Cumulus Media Inc. -

Group Ownership

Group Ownership Grant Broadcasting System II Inc., Box 2127. Roanoke, Note: CJMD(AM) Chibougamau is rebroadcast by Petersburg) and WPBF(TV) Tequesta (West Palm Beach). VA (24009). (540) 344 -2127. Fax: (540) 345 -1912. Web CFED(AM) Chapais, PQ. (All stns located in Canada.) both FL: WBAL-AM Baltimore. MD; KQCA(TV) Stockton, Site: www.fox2127.com. Executives: Milton Grant, Ownership: Gestion Maley Inc., 50 %; Gestion Tremblay CA. Loc mktg agreement: KCWE(TV) Kansas City, MO. pres /sec/treas; Ben Klien, asst sec; Carol L. Callahan, asst & Leclerc Inc., 50 %. Ownership: The Hearst Corp., 66% sec. Stns: 3 TV. WJPR(TV) Lynchburg and WFXR -TV Groupe TVA Inc., Tele -4 /CFCM -TV, 1000 Myrand Ave.. Heartland Broadcasting Corp., 7891 U.S. Hwy 17 S., Roanoke, WBVA(TV) Roanoke-Lynchburg, all VA. (Both Ste. -Foy, PQ (G1V 2W3). Canada. (418) 688 -9330. Fax: Zolfo Springs. FL (33890). (863) 494 -4111. E -mail: 100% owned.) (418) 681 -4239. Dania! Lamarre, pres. wzzsedesoto.net. Web Site: www.desoto.net/wzzs. Ownership: Milton Grant. Stns: 5 TV. CJPM -TV Chicoutimi, CFCM -TV Quebec Harold M. Kneller Jr., pros; Janet K. Kneller, sec/treas; City, CFER -TV Rimouski, CHLT-TV Sherbrooke and Wm. D. Noel Jr.. VP. Grant Media Inc., 915 Middle River Dr., Suite 409, Fort -TV Trois PO. located in CHEM -Rivieres, all (All sins are Stns: 1 AM. 2 FM. WZTK(AM) Arcadia, WZSP(FM) Lauderdale, FL (33304). (954) 568 -2000. Fax: (954) Canada.) Nocatee and WZZS(FM) Zolfo Springs, all FL. (All 100% 568-2015. Barb Quillin, progmg mgr. Ownership: Groupe Videotron Ltee. -

2019 Annual Report

A TEAM 2019 ANNU AL RE P ORT Letter to our Shareholders Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. Dear Fellow Shareholders, BOARD OF DIRECTORS CORPORATE OFFICERS ANNUAL MEETING David D. Smith David D. Smith The Annual Meeting of stockholders When I wrote you last year, I expressed my sincere optimism for the future of our Company as we sought to redefine the role of a Chairman of the Board, Executive Chairman will be held at Sinclair Broadcast broadcaster in the 21st Century. Thanks to a number of strategic acquisitions and initiatives, we have achieved even greater success Executive Chairman Group’s corporate offices, in 2019 and transitioned to a more diversified media company. Our Company has never been in a better position to continue to Frederick G. Smith 10706 Beaver Dam Road grow and capitalize on an evolving media marketplace. Our achievements in 2019, not just for our bottom line, but also our strategic Frederick G. Smith Vice President Hunt Valley, MD 21030 positioning for the future, solidify our commitment to diversify and grow. As the new decade ushers in technology that continues to Vice President Thursday, June 4, 2020 at 10:00am. revolutionize how we experience live television, engage with consumers, and advance our content offerings, Sinclair is strategically J. Duncan Smith poised to capitalize on these inevitable changes. From our local news to our sports divisions, all supported by our dedicated and J. Duncan Smith Vice President INDEPENDENT REGISTERED PUBLIC innovative employees and executive leadership team, we have assembled not only a winning culture but ‘A Winning Team’ that will Vice President, Secretary ACCOUNTING FIRM serve us well for years to come. -

Converged Markets

Converged Markets - Converged Power? Regulation and Case Law A publication series of the Market power becomes an issue for European and media services and enabling services, platforms and European Audiovisual Observatory national law makers whenever market players acquire a converged services, and fi nally distribution services. degree of power which severely disturbs the market balance. In this sense, the audiovisual sector is no The eleven countries were selected for this study because exception. But this sector is different in that too much they either represented major markets for audiovisual market power may not only endanger the competitive media services in Europe, or because they developed out- parameters of the sector but may also become a threat side the constraints of the internal market, or because they had some interesting unique feature, for example to the freedom of information. It is this latter aspect the ability to attract major market players despite lacking which turns market power into a particularly sensitive an adequately sized market. issue for the audiovisual sector. National legislators and regulators backed by national courts seek solutions The third part brings in the economic background in the adapted to this problem. form of different overviews concerning audience market shares for television and video online. This data puts the This IRIS Special issue is deals with the regulation of legal information into an everyday context. market power in the audiovisual sector in Europe. The fourth and fi nal part seeks to tie together the common The fi rst part of this IRIS Special explores the European threads in state regulation of media power, to work Union’s approach to limiting media power, an approach out the main differences and to hint to some unusual still dominated by the application of competition law.