Gnetophyta. Class and Ordinal Rank, Respectively

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antarctic Bryophyte Research—Current State and Future Directions

Bry. Div. Evo. 043 (1): 221–233 ISSN 2381-9677 (print edition) DIVERSITY & https://www.mapress.com/j/bde BRYOPHYTEEVOLUTION Copyright © 2021 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 2381-9685 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/bde.43.1.16 Antarctic bryophyte research—current state and future directions PAULO E.A.S. CÂMARA1, MicHELine CARVALHO-SILVA1 & MicHAEL STecH2,3 1Departamento de Botânica, Universidade de Brasília, Brazil UnB; �[email protected]; http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3944-996X �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2389-3804 2Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, Netherlands; 3Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9804-0120 Abstract Botany is one of the oldest sciences done south of parallel 60 °S, although few professional botanists have dedicated themselves to investigating the Antarctic bryoflora. After the publications of liverwort and moss floras in 2000 and 2008, respectively, new species were described. Currently, the Antarctic bryoflora comprises 28 liverwort and 116 moss species. Furthermore, Antarctic bryology has entered a new phase characterized by the use of molecular tools, in particular DNA sequencing. Although the molecular studies of Antarctic bryophytes have focused exclusively on mosses, molecular data (fingerprinting data and/or DNA sequences) have already been published for 36 % of the Antarctic moss species. In this paper we review the current state of Antarctic bryological research, focusing on molecular studies and conservation, and discuss future questions of Antarctic bryology in the light of global challenges. Keywords: Antarctic flora, conservation, future challenges, molecular phylogenetics, phylogeography Introduction The Antarctic is the most pristine, but also most extreme region on Earth in terms of environmental conditions. -

New Paleobotanical Data on the Portuguese Pennsylvanian (Douro Carboniferous Basin, NW Portugal)

Versão online: http://www.lneg.pt/iedt/unidades/16/paginas/26/30/185 Comunicações Geológicas (2014) 101, Especial I, 409-414 IX CNG/2º CoGePLiP, Porto 2014 ISSN: 0873-948X; e-ISSN: 1647-581X New paleobotanical data on the Portuguese Pennsylvanian (Douro Carboniferous Basin, NW Portugal) Novos dados paleobotânicos do Pensilvaniano português (Bacia Carbonífera do Douro, NW Portugal) P. Correia1*, Z. Šimůnek2, J. Pšenička3, A. A. Sá4,5, R. Domingos6, A. Carneiro7, D. Flores1,7 Artigo Curto Short Article © 2014 LNEG – Laboratório Nacional de Geologia e Energia IP Abstract: This paper describes nine new macrofloral taxa from 1. Introduction Douro Carboniferous Basin (lower Gzhelian) of Portugal. The plant assemblage is mainly composed by pteridophylls (Sphenopteriss The fossil flora of Carboniferous of Portugal is still little arberi Kidston, Sphenopteris fayoli Zeiller, Sphenopteris tenuis known. The new megafloral occurrences recently found in Schenk, Odontopteris schlotheimii Brongniart), sphenopsids the Upper Pennsylvanian strata of Douro Carboniferous (Annularia spicata Gutbier, Stellotheca robusta (Feistmantel) Basin (DCB) provide new and important data about Surange and Prakash, Calamostachys grandis Zeiller (Jongmans) and Calamostachys calathifera Sterzel) besides the gymnosperm paleobotanical richness and diversity of the Paleozoic Cordaites foliolatus Grand`Eury. The new data provide a better floras of Portugal offering more information to previous understating of the knowledge of Late Carboniferous floras of researches reported from diverse localities and by different Portugal, showing the high plant diversity of Gzhelian floras, when authors (e.g. Wenceslau de Lima, Bernardino António considerable changes in paleogeography and climate dynamics are Gomes, Carlos Ribeiro, Carríngton da Costa, Carlos evidenced in Euramerican floristic assemblages. -

Plant Evolution an Introduction to the History of Life

Plant Evolution An Introduction to the History of Life KARL J. NIKLAS The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 1 Origins and Early Events 29 2 The Invasion of Land and Air 93 3 Population Genetics, Adaptation, and Evolution 153 4 Development and Evolution 217 5 Speciation and Microevolution 271 6 Macroevolution 325 7 The Evolution of Multicellularity 377 8 Biophysics and Evolution 431 9 Ecology and Evolution 483 Glossary 537 Index 547 v Introduction The unpredictable and the predetermined unfold together to make everything the way it is. It’s how nature creates itself, on every scale, the snowflake and the snowstorm. — TOM STOPPARD, Arcadia, Act 1, Scene 4 (1993) Much has been written about evolution from the perspective of the history and biology of animals, but significantly less has been writ- ten about the evolutionary biology of plants. Zoocentricism in the biological literature is understandable to some extent because we are after all animals and not plants and because our self- interest is not entirely egotistical, since no biologist can deny the fact that animals have played significant and important roles as the actors on the stage of evolution come and go. The nearly romantic fascination with di- nosaurs and what caused their extinction is understandable, even though we should be equally fascinated with the monarchs of the Carboniferous, the tree lycopods and calamites, and with what caused their extinction (fig. 0.1). Yet, it must be understood that plants are as fascinating as animals, and that they are just as important to the study of biology in general and to understanding evolutionary theory in particular. -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

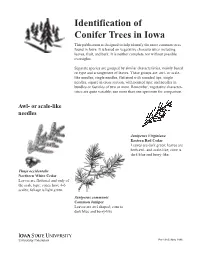

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

Chlorophyta Is a Division of Green Algae, Informally Called

Chlorophyta is a division of green algae, informally waters of the Sargasso Sea. Many brown algae, such as called chlorophytes. The name is used in two very members of the order Fucales, commonly grow along different senses so that care is needed to determine the rocky seashores. Some members of the class are used as use by a particular author. In older classification food for humans. systems, it refers to a highly paraphyletic group of all Worldwide there are about 1500–2000 species of brown the green algae within the green plants (Viridiplantae), algae.[4] Some species are of sufficient commercial and thus includes about 7,000 species [4] [5] of mostly importance, such as Ascophyllum nodosum , that they aquatic photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. Like the have become subjects of extensive research in their own land plants (bryophytes and tracheophytes), green algae right.[5] [4] contain chlorophylls a and b, and store food as starch Brown algae belong to a very large group, the in their plastids. Heterokontophyta, a eukaryotic group of organisms In newer classifications, it refers to one of the two distinguished most prominently by having chloroplasts clades making up the Viridiplantae, which are the surrounded by four membranes, suggesting an origin chlorophytes and the streptophytes or charophytes.[6][7] from a symbiotic relationship between a basal In this sense it includes only about 4,300 species.[3] eukaryote and another eukaryotic organism. Most brown algae contain the pigment fucoxanthin, which is responsible for the distinctive greenish-brown color that The red algae, or Rhodophyta ( / r o ʊ ˈ d ɒ f ɨ t ə / or / gives them their name. -

Seed Germination and Genetic Structure of Two Salvia Species In

Seed germination and genetic structure of two Salvia species in response to environmental variables among phytogeographic regions in Jordan (Part I) and Phylogeny of the pan-tropical family Marantaceae (Part II). Dissertation Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat) Vorgelegt der Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät I Biowissenschaften der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg Von Herrn Mohammad Mufleh Al-Gharaibeh Geb. am: 18.08.1979 in: Irbid-Jordan Gutachter/in 1. Prof. Dr. Isabell Hensen 2. Prof. Dr. Martin Roeser 3. Prof. Dr. Regina Classen-Bockhof Halle (Saale), den 10.01.2017 Copyright notice Chapters 2 to 4 have been either published in or submitted to international journals or are in preparation for publication. Copyrights are with the authors. Just the publishers and authors have the right for publishing and using the presented material. Therefore, reprint of the presented material requires the publishers’ and authors’ permissions. “Four years ago I started this project as a PhD project, but it turned out to be a long battle to achieve victory and dreams. This dissertation is the culmination of this long process, where the definition of “Weekend” has been deleted from my dictionary. It cannot express the long days spent in analyzing sequences and data, battling shoulder to shoulder with my ex- computer (RIP), R-studio, BioEdite and Microsoft Words, the joy for the synthesis, the hope for good results and the sadness and tiredness with each attempt to add more taxa and analyses.” “At the end, no phrase can describe my happiness when I saw the whole dissertation is printed out.” CONTENTS | 4 Table of Contents Summary .......................................................................................................................................... -

Predatory Flagellates – the New Recently Discovered Deep Branches of the Eukaryotic Tree and Their Evolutionary and Ecological Significance

Protistology 14 (1), 15–22 (2020) Protistology Predatory flagellates – the new recently discovered deep branches of the eukaryotic tree and their evolutionary and ecological significance Denis V. Tikhonenkov Papanin Institute for Biology of Inland Waters, Russian Academy of Sciences, Borok, 152742, Russia | Submitted March 20, 2020 | Accepted April 6, 2020 | Summary Predatory protists are poorly studied, although they are often representing important deep-branching evolutionary lineages and new eukaryotic supergroups. This short review/opinion paper is inspired by the recent discoveries of various predatory flagellates, which form sister groups of the giant eukaryotic clusters on phylogenetic trees, and illustrate an ancestral state of one or another supergroup of eukaryotes. Here we discuss their evolutionary and ecological relevance and show that the study of such protists may be essential in addressing previously puzzling evolutionary problems, such as the origin of multicellular animals, the plastid spread trajectory, origins of photosynthesis and parasitism, evolution of mitochondrial genomes. Key words: evolution of eukaryotes, heterotrophic flagellates, mitochondrial genome, origin of animals, photosynthesis, predatory protists, tree of life Predatory flagellates and diversity of eu- of the hidden diversity of protists (Moon-van der karyotes Staay et al., 2000; López-García et al., 2001; Edg- comb et al., 2002; Massana et al., 2004; Richards The well-studied multicellular animals, plants and Bass, 2005; Tarbe et al., 2011; de Vargas et al., and fungi immediately come to mind when we hear 2015). In particular, several prevailing and very abun- the term “eukaryotes”. However, these groups of dant ribogroups such as MALV, MAST, MAOP, organisms represent a minority in the real diversity MAFO (marine alveolates, stramenopiles, opistho- of evolutionary lineages of eukaryotes. -

The Effects of Sulphur Dioxide on Selected Hepatics" (1978)

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1978 The ffecE ts of Sulphur Dioxide on Selected Hepatics Steven L. Gatchel Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Botany at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Gatchel, Steven L., "The Effects of Sulphur Dioxide on Selected Hepatics" (1978). Masters Theses. 3192. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3192 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPF-:R CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a ' number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date Author I respectfully request Booth Library of .Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because---------------- Date Author pdm THE EFFECTS OF SULPHUR DIOXIDE ON SELECTED HEPATICS (TITLE} BY Steven L. Gatchel THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1978 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE GRADUATE DEGREE CITED ABOVE ol}-~ d2/, 19"/f DATE ADVISER I/ 'Ouue~2\ 1\l~ DATE ' ~RTMENT WHEAD THE EFFECTS OF SULPHUR DIOXIDE ON SELECTED HEPATICS BY STEVEN L. -

Aquatic and Wet Marchantiophyta, Order Metzgeriales: Aneuraceae

Glime, J. M. 2021. Aquatic and Wet Marchantiophyta, Order Metzgeriales: Aneuraceae. Chapt. 1-11. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte 1-11-1 Ecology. Volume 4. Habitat and Role. Ebook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 11 April 2021 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 1-11: AQUATIC AND WET MARCHANTIOPHYTA, ORDER METZGERIALES: ANEURACEAE TABLE OF CONTENTS SUBCLASS METZGERIIDAE ........................................................................................................................................... 1-11-2 Order Metzgeriales............................................................................................................................................................... 1-11-2 Aneuraceae ................................................................................................................................................................... 1-11-2 Aneura .......................................................................................................................................................................... 1-11-2 Aneura maxima ............................................................................................................................................................ 1-11-2 Aneura mirabilis .......................................................................................................................................................... 1-11-7 Aneura pinguis .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Seed Plant Phylogeny: Demise of the Anthophyte Hypothesis? Michael J

bb10c06.qxd 02/29/2000 04:18 Page R106 R106 Dispatch Seed plant phylogeny: Demise of the anthophyte hypothesis? Michael J. Donoghue* and James A. Doyle† Recent molecular phylogenetic studies indicate, The first suggestions that Gnetales are related to surprisingly, that Gnetales are related to conifers, or angiosperms were based on several obvious morphological even derived from them, and that no other extant seed similarities — vessels in the wood, net-veined leaves in plants are closely related to angiosperms. Are these Gnetum, and reproductive organs made up of simple, results believable? Is this a clash between molecules unisexual, flower-like structures, which some considered and morphology? evolutionary precursors of the flowers of wind-pollinated Amentiferae, but others viewed as being reduced from Addresses: *Harvard University Herbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA. †Section of Evolution and more complex flowers in the common ancestor of Ecology, University of California, Davis, California 95616, USA. angiosperms, Gnetales and Mesozoic Bennettitales [1]. E-mail: [email protected] These ideas went into eclipse with evidence that simple [email protected] flowers really are a derived, rather than primitive, feature Current Biology 2000, 10:R106–R109 of the Amentiferae, and that vessels arose independently in angiosperms and Gnetales. Vessels in angiosperms 0960-9822/00/$ – see front matter seem derived from tracheids with scalariform pits, whereas © 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. in Gnetales they resemble tracheids with circular bor- dered pits, as in conifers. Gnetales are also like conifers in These are exciting times for those interested in plant lacking scalariform pitting in the primary xylem, and in evolution. -

Ecophysiology of Four Co-Occurring Lycophyte Species: an Investigation of Functional Convergence

Research Article Ecophysiology of four co-occurring lycophyte species: an investigation of functional convergence Jacqlynn Zier, Bryce Belanger, Genevieve Trahan and James E. Watkins* Department of Biology, Colgate University, Hamilton, NY 13346, USA Received: 22 June 2015; Accepted: 7 November 2015; Published: 24 November 2015 Associate Editor: Tim J. Brodribb Citation: Zier J, Belanger B, Trahan G, Watkins JE. 2015. Ecophysiology of four co-occurring lycophyte species: an investigation of functional convergence. AoB PLANTS 7: plv137; doi:10.1093/aobpla/plv137 Abstract. Lycophytes are the most early divergent extant lineage of vascular land plants. The group has a broad global distribution ranging from tundra to tropical forests and can make up an important component of temperate northeast US forests. We know very little about the in situ ecophysiology of this group and apparently no study has eval- uated if lycophytes conform to functional patterns expected by the leaf economics spectrum hypothesis. To determine factors influencing photosynthetic capacity (Amax), we analysed several physiological traits related to photosynthesis to include stomatal, nutrient, vascular traits, and patterns of biomass distribution in four coexisting temperate lycophyte species: Lycopodium clavatum, Spinulum annotinum, Diphasiastrum digitatum and Dendrolycopodium dendroi- deum. We found no difference in maximum photosynthetic rates across species, yet wide variation in other traits. We also found that Amax was not related to leaf nitrogen concentration and is more tied to stomatal conductance, suggestive of a fundamentally different sets of constraints on photosynthesis in these lycophyte taxa compared with ferns and seed plants. These findings complement the hydropassive model of stomatal control in lycophytes and may reflect canaliza- tion of function in this group.