Bringing Little Things to the Surface: Intervening Into the Japanese Post-Bubble Impasse on the Yamanote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Otorisama Continues to Be Loved by the People

2020 edition Edo to the Present The Sugamo Otori Shrine, located near the Nakasendo, has been providing a spiritual Ⅰ Otorisama continues to be loved sanctuary to the people as Oinarisama (Inari god) and continues to be worshipped and by the people loved to this today. Torinoichi, the legacy of flourishing Edo Stylish manners of Torinoichi The Torinoichi is famous for its Kaiun Kumade Mamori (rake-shaped amulet for Every November on the day of the good luck). This very popular good luck charm symbolizes prosperous business cock, the Torinoichi (Cock Fairs) are and is believed to rake in better luck with money. You may hear bells ringing from all held in Otori Shrines across the nation parts of the precinct. This signifies that the bid for the rake has settled. The prices and many worshippers gather at the of the rakes are not fixed so they need to be negotiated. The customer will give the Sugamo Otori Shrine. Kumade vendor a portion of the money saved from negotiation as gratuity so both The Sugamo Otori Shrine first held parties can pray for successful business. It is evident through their stylish way of business that the people of Edo lived in a society rich in spirit. its Torinoichi in 1864. Sugamo’s Torinoichi immediately gained good reputation in Edo and flourished year Kosodateinari / Sugamo Otori Shrine ( 4-25 Sengoku, Bunkyo Ward ) MAP 1 after year. Sugamo Otori Shrine was established in 1688 by a Sugamo resident, Shin However, in 1868, the new Meiji Usaemon, when he built it as Sugamoinari Shrine. -

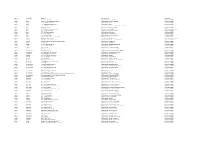

List of Certified Facilities (Cooking)

List of certified facilities (Cooking) Prefectures Name of Facility Category Municipalities name Location name Kasumigaseki restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Second floor,Tokyo-club Building,3-2-6,Kasumigaseki,Chiyoda-ku Second floor,Sakura terrace,Iidabashi Grand Bloom,2-10- ALOHA TABLE iidabashi restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 2,Fujimi,Chiyoda-ku The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku banquet kitchen The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 24th floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku Peter The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Boutique & Café First basement, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Second floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku Hei Fung Terrace The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku First floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku The Lobby 1-1-1,Uchisaiwai-cho,Chiyoda-ku TORAYA Imperial Hotel Store restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku (Imperial Hotel of Tokyo,Main Building,Basement floor) mihashi First basement, First Avenu Tokyo Station,1-9-1 marunouchi, restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku (First Avenu Tokyo Station Store) Chiyoda-ku PALACE HOTEL TOKYO(Hot hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-1-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku Kitchen,Cold Kitchen) PALACE HOTEL TOKYO(Preparation) hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-1-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku LE PORC DE VERSAILLES restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku First~3rd floor, Florence Kudan, 1-2-7, Kudankita, Chiyoda-ku Kudanshita 8th floor, Yodobashi Akiba Building, 1-1, Kanda-hanaoka-cho, Grand Breton Café -

TOKYO TRAIN & SUBWAY MAP JR Yamanote

JR Yamanote Hibiya line TOKYO TRAIN & SUBWAY MAP Ginza line Chiyoda line © Tokyo Pocket Guide Tozai line JR Takasaka Kana JR Saikyo Line Koma line Marunouchi line mecho Otsuka Sugamo gome Hanzomon line Tabata Namboku line Ikebukuro Yurakucho line Shin- Hon- Mita Line line A Otsuka Koma Nishi-Nippori Oedo line Meijiro Sengoku gome Higashi Shinjuku line Takada Zoshigaya Ikebukuro Fukutoshin line nobaba Todai Hakusan Mae JR Joban Asakusa Nippori Line Waseda Sendagi Gokokuji Nishi Myogadani Iriya Tawara Shin Waseda Nezu machi Okubo Uguisu Seibu Kagurazaka dani Inaricho JR Shinjuku Edo- Hongo Chuo gawa San- Ueno bashi Kasuga chome Naka- Line Higashi Wakamatsu Okachimachi Shinjuku Kawada Ushigome Yushima Yanagicho Korakuen Shin-Okachi Ushigome machi Kagurazaka B Shinjuku Shinjuku Ueno Hirokoji Okachimachi San-chome Akebono- Keio bashi Line Iidabashi Suehirocho Suido- Shin Gyoen- Ocha Odakyu mae Bashi Ocha nomizu JR Line Yotsuya Ichigaya no AkihabaraSobu Sanchome mizu Line Sendagaya Kodemmacho Yoyogi Yotsuya Kojimachi Kudanshita Shinano- Ogawa machi Ogawa Kanda Hanzomon Jinbucho machi Kokuritsu Ningyo Kita Awajicho -cho Sando Kyogijo Naga Takebashi tacho Mitsu koshi Harajuku Mae Aoyama Imperial Otemachi C Meiji- Itchome Kokkai Jingumae Akasaka Gijido Palace Nihonbashi mae Inoka- Mitsuke Sakura Kaya Niju- bacho shira Gaien damon bashi bacho Tameike mae Tokyo Line mae Sanno Akasaka Kasumi Shibuya Hibiya gaseki Kyobashi Roppongi Yurakucho Omotesando Nogizaka Ichome Daikan Toranomon Takaracho yama Uchi- saiwai- Hachi Ebisu Hiroo Roppongi Kamiyacho -

Outer Loop Oimachi Shonan-Shinjuku Line Omori Kamata Emolga Keihin-Tohoku Line

URL http://www.webmtabi.jp/201208/print/pokemon_yamanote-line_en.pdf 2012.8 >> JR Yamanote Line Outer Tracks Pokemon Stamp Rally 2012 Guide www.webmtabi.jp Secret? Akabane Secret? Higashi-Jujo Oji Kita-Senju Takasaki Line Oku Jujo Kami-Nakazato Tabata Joban Line Black Kyurem Itabashi Nishi-Nippori Minami-Senju Komagome MikawashimaOshawott Ikebukuro Nippori Sugamo Mejiro Ootsuka Uguisudani Goal Ueno Vanillite Takadanobaba Okachimachi Nakano Ichigaya IidabashiSuidobashi White Kyurem Shin-Okubo Higashi-NakanoOkubo Shinanomachi Akihabara Sendagaya Shinjuku Yotsuya Ochanomizu Chuo Line, Sobu Line Chuo Line Kanda Goal Yoyogi Pansage (Local Train) (Limited Express) Tokyo Cryogonal Harajuku Kyurem Yurakucho Shibuya Shimbashi Ebisu Yamanote Line Meguro Hamamatsucho Snivy Gotanda Secret? Tamachi Saikyo Line Shinagawa Osaki Outer loop Oimachi Shonan-Shinjuku Line Omori Kamata Emolga Keihin-Tohoku Line ○○○ ○○○ Goal Stairway Elevator Escalator Station Stamp Desk To Shinagawa Shibuya 2 On board for 2 minutes Car No.11 Door #4 Ticket Gate TOKYO (Kyurem[Kyuremu]) Yamanote Line Yamanote Line Outer Tracks - No.5 Tabata Marunouchi Central Exit Nishi-Nippori Car No.5 Door #1 Nippori To Shinagawa Uguisudani Ueno Shibuya 1 3 5 7 9 11 2 Marunouchi Underground Okachimachi North Exit Akihabara Kanda South Passage Central Passage North Passage Tokyo Yurakucho Shimbashi Hamamatsucho Tamachi Yurakucho Shinagawa ↑ Local Train Rapid Service 2 Keihin-Tohoku Line 1/4 URL http://www.webmtabi.jp/201208/print/pokemon_yamanote-line_en.pdf ○○○ ○○○ Goal Stairway Elevator -

Shibuya City Industry and Tourism Vision

渋谷区 Shibuya City Preface Preface In October 2016, Shibuya City established the Shibuya City Basic Concept with the goal of becoming a mature international city on par with London, Paris, and New York. The goal is to use diversity as a driving force, with our vision of the future: 'Shibuya—turning difference into strength'. One element of the Basic Concept is setting a direction for the Shibuya City Long-Term Basic Plan of 'A city with businesses unafraid to take risks', which is a future vision of industry and tourism unique to Shibuya City. Each area in Shibuya City has its own unique charm with a collection of various businesses and shops, and a great number of visitors from inside Japan and overseas, making it a place overflowing with diversity. With the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games being held this year, 2020 is our chance for Shibuya City to become a mature international city. In this regard, I believe we must make even further progress in industry and tourism policies for the future of the city. To accomplish this, I believe a plan that further details the policies in the Long-Term Basic Plan is necessary, which is why the Industry and Tourism Vision has been established. Industry and tourism in Shibuya City faces a wide range of challenges that must be tackled, including environmental improvements and safety issues for accepting inbound tourism and industry. In order to further revitalize the shopping districts and small to medium sized businesses in the city, I also believe it is important to take on new challenges such as building a startup ecosystem and nighttime economy. -

Tokyo Metoropolitan Area Railway and Subway Route

NikkNikkō Line NikkNikkō Kuroiso Iwaki Tōbu-nikbu-nikkkō Niigata Area Shimo-imaichi ★ ★ Tōbu-utsunomiya Shin-fujiwara Shibata Shin-tochigi Utsunomiya Line Nasushiobara Mito Uetsu Line Network Map Hōshakuji Utsunomiya Line SAITAMA Tōhoku Shinkansen Utsunomiya Tomobe Ban-etsu- Hakushin Line Hakushin Line Niitsu WestW Line ■Areas where Suica・PASMO can be used RAILWAY Tochigi Oyama Shimodate Mito Line Niigata est Line Shinkansen Moriya Tsukuba Jōmō- Jōetsu Minakami Jōetsu Akagi Kuzū Kōgen ★ Shibukawa Line Shim-Maebashi Ryōmō Line Isesaki Sano Ryōmō Line Hokuriku Kurihashi Minami- ban Line Takasaki Kuragano Nagareyama Gosen Shinkansen(via Nagano) Takasaki Line Minami- Musashino Line NagareyamaNagareyama-- ō KukiKuki J Ōta Tōbu- TOBU Koshigaya ōōtakanomoritakanomori Line Echigo Jōetsu ShinkansenShinkansen Shin-etsu Line Line Annakaharuna Shin-etsu Line Nishi-koizumi Tatebayashi dōbutsu-kōen Kasukabe Shin-etsu Line Yokokawa Kumagaya Higashi-kHigashi-koizumioizumi Tsubamesanjō Higashi- Ogawamachi Sakado Shin- Daishimae Nishiarai Sanuki SanjSanjōō Urawa-Misono koshigaya Kashiwa Abiko Yahiko Minumadai- Line Uchijuku Ōmiya Akabane- Nippori-toneri Liner Ryūgasaki Nagaoka Kawagoeshi Hon-Kawagoe Higashi- iwabuchi Kumanomae shinsuikoen Toride Yorii Ogose Kawaguchi Machiya Kita-ayase TSUKUBA Yahiko Yoshida HachikHachikō Line Kawagoe Line Kawagoe ★ ★ NEW SHUTTLE Komagawa Keihin-Tōhoku Line Ōji Minami-Senju EXPRESS Shim- Shinkansen Ayase Kanamachi Matsudo ★ Seibu- Minami- Sendai Area Higashi-HanHigashi-Hannnō Nishi- Musashino Line Musashi-Urawa Akabane -

Japanese Language Classes by Volunteers Groups

Japanese Language Classes by Volunteers Groups Tokyo YMCA Shinjyuku Niji no Kai Club of children and students ATOMU Nihongo Kyoshitsu Akebono-kai Akebono-kai Tsunohazu Nihongo Kyoshitsu Akebonobashi Nihongo Kyoshitsu Venue:Tokyo YMCA Yamate Community Center Family Japanese Language working together for Venue:Zainichi Gaikokujin Joho Center (ICFJ) Address:Shinjuku-ku Nishi-waseda 2-18-12 Address:Shinjuku-ku Takadanobaba 1-26-12 Venue:Tsunohazu Chiiki Center Venue:Gender Equality Promotion Center 3rd fl. Line/Nearest Station:* 7-min. walk from Takadanobaba Class multicultural society Takadanobaba-build. 405 Address:Shinjuku-ku Nishi-shinjuku 4-33-7 Address:shinjuku-ku Arakicho 16 Sta. on the JR Yamanote Line, Line/Nearest Station:* 3-min. walk from Takadanobaba Line/Nearest Station *10-min. walk from Hatsudai Sta. Line/Nearest Station:* 3-min. walk from Akebonobashi Venue:Shinjuku-ku Okubo Elementary School Venue:Okubo Chiiki Center 3rd Fl. Conference Room Seibu Shinjuku Line, (Exit 7) on Sta. on the JR and Seibu Shinjuku on the Keio New Line Sta.(Exit A4) on the Toei Shinjuku Address:Shinjuku-ku Okubo 1-1-21 Address:Shinjuku-ku Okubo 2-12-7 the Tokyo Metoro Tozai Line Line *10-min. walk from Tochomae Line Line/Nearest Station:*15-min. walk from Shinokubo Sta. Line/Nearest Station:* 7-min. walk from Shinokubo Sta. * 3-min. walk from Nishiwaseda * 5-min. walk from Takadanobaba Sta.(Exit A5) on the Toei Oedo *10-min. walk from Yotsuya on the JR yamanote Line, on the JR yamanote Line Sta.(Exit 1) on the Tokyo Metro Sta.(Exit 5) on the Tokyo Metro Line 3chome Sta. -

Notice Concerning Property Acquisition(Premier Stage Komagome)

October 30, 2006 For Immediate Release REIT Issuer Premier Investment Corporation 1-2-7 Nishi Azabu, Minato Ward, Tokyo Executive Director Hiroshi Matsuzawa (Securities Code 8956) Investment Trust Management Company Premier REIT Advisors Co., Ltd. President & CEO Fumihiro Yasutake [Contact] Director & Head of REIT Management Division Fumio Suzuki TEL: +81-3-5772-8551 Notice Concerning Property Acquisition <Premier Stage Komagome> Premier Investment Corporation (“Premier”) announces its decision today to acquire the property outlined below and that a real estate trust beneficiary interests transfer agreement was executed. 1. Overview of Acquisition (1) Property Name Premier Stage Komagome (hereinafter, the “Property”) (2) Type of Beneficiary interests in a trust (real estate) Acquisition (3) Acquisition Price 1,830 million yen (excluding acquisition costs, fixed asset tax, city planning tax, consumption tax and local consumption tax) <Payment Schedule> Pay 50 million yen (down payment) upon execution of real estate trust beneficiary interest transfer agreement Pay 1,780 million yen (remaining amount) upon transfer (4) Scheduled Date October 30, 2006 of Acquisition Execution of real estate trust beneficiary interests transfer agreement (subject to condition precedents; refer to “2. Reason for Acquisition (3) Significance, etc. of Acquiring the Property (ii)” below for an outline of the condition precedents) February 28, 2007 (scheduled) Execution of transfer in accordance with the abovementioned real estate trust beneficiary interests transfer agreement (when condition precedents are fulfilled) (5) Seller Meiho Enterprise Co., Ltd. (refer to “4. Seller Profile” below) (6) Financing Cash on hand and debt financing 2. Reason for Acquisition The Property will be acquired for the following reason in accordance with the “Property Management Targets and Policies” stipulated in the Articles of Incorporation of Premier. -

Confirmation Notice/ 6 July 2019/ Tokyo-Takadanobaba Thank You So Much for Your Registration for IELTS Test

Confirmation Notice/ 6 July 2019/ Tokyo-Takadanobaba Thank you so much for your registration for IELTS test. This is to inform you of the details for IELTS test. You will receive the speaking confirmation notice via e-mail by 2 days before the test. You can also confirm your speaking test time on Booking Summary Page of your account after receiving the e-mail. Please do not forget to bring your valid passport on the test day. (Please also refer to the information below.) (Written Tests) (Speaking Test) Your venue (1 or 2) will be informed by e-mail. ◆ Test Date: 6 July 2019 (AM) ◆ Test Date: 6 July 2019 (PM) ◆ Venue: Tokyo Fuji University, Main Building 1F (3-8-1 ◆ Venue 1: Japan Study Abroad Foundation 3F (Taiju Takadanobaba, Shinjuku-ku Tokyo 169-0075 Japan) Seimei Bldg. 3F, 1-4-15, Takadanobaba, Shinjuku-ku ◆ Access: From Takadanobaba Station (JR Line, Seibu Shinjuku Tokyo 169-0075 Japan) Line, Tokyo Metro Tozai Line): About 5minute walk/ From Shimo ◆ Access: From JR/Seibu Takadanobaba Station: About 6 Ochiai Station (Seibu Shinjuku Line): About 5minute walk minute walk/ From Tokyo Metro Tozai Line Takadanobaba http://www.fuji.ac.jp/access/ Station: About 3 minute walk/ From Tokyo Metro http://www.fuji.ac.jp/guidance/facility/ (Campus Map) Fukutoshin-line Nishi-Waseda Station : About 4 minute ◆ Arrival Time: 8:30am walk ◆ ID Check: 8:30am-8:55am http://www.japanstudyabroad.org/?page_id=6636 ◆ Test Start: 9:00am ◆ Venue 2: Tokyo Fuji University, Main Building 5F (3-8-1 ◆ Test Finish: 12:20pm (approx.) Takadanobaba, Shinjuku-ku Tokyo 169-007 Japan) ※Same place as where Written parts will be taken place. -

Area Locality Address Description Operator Aichi Aisai 10-1

Area Locality Address Description Operator Aichi Aisai 10-1,Kitaishikicho McDonald's Saya Ustore MobilepointBB Aichi Aisai 2283-60,Syobatachobensaiten McDonald's Syobata PIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Ama 2-158,Nishiki,Kaniecho McDonald's Kanie MobilepointBB Aichi Ama 26-1,Nagamaki,Oharucho McDonald's Oharu MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 1-18-2 Mikawaanjocho Tokaido Shinkansen Mikawa-Anjo Station NTT Communications Aichi Anjo 16-5 Fukamachi McDonald's FukamaPIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 2-1-6 Mikawaanjohommachi Mikawa Anjo City Hotel NTT Communications Aichi Anjo 3-1-8 Sumiyoshicho McDonald's Anjiyoitoyokado MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 3-5-22 Sumiyoshicho McDonald's Anjoandei MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 36-2 Sakuraicho McDonald's Anjosakurai MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 6-8 Hamatomicho McDonald's Anjokoronaworld MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo Yokoyamachiyohama Tekami62 McDonald's Anjo MobilepointBB Aichi Chiryu 128 Naka Nakamachi Chiryu Saintpia Hotel NTT Communications Aichi Chiryu 18-1,Nagashinochooyama McDonald's Chiryu Gyararie APITA MobilepointBB Aichi Chiryu Kamishigehara Higashi Hatsuchiyo 33-1 McDonald's 155Chiryu MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-1 Ichoden McDonald's Higashiura MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-1711 Shimizugaoka McDonald's Chitashimizugaoka MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-3 Aguiazaekimae McDonald's Agui MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 24-1 Tasaki McDonald's Taketoyo PIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 67?8,Ogawa,Higashiuracho McDonald's Higashiura JUSCO MobilepointBB Aichi Gamagoori 1-3,Kashimacho McDonald's Gamagoori CAINZ HOME MobilepointBB Aichi Gamagori 1-1,Yuihama,Takenoyacho -

Shinjukunews

Shinjuku News Published by: Multicultural Society Promotion Division, Foreign Language Website No. 34 Regional and Cultural Affairs Department, Shinjuku City 1-4-1 Kabuki-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-8484 www.city.shinjuku.lg.jp/foreign/english/ Publishing Date: September 30, 2013 Tel: 03-5273-3504 Fax: 03-3209-1500 Please make your inquiries in Japanese when calling the coordinating division. DiscoverDiscover thethe PleasuresPleasures ofof YourYour LocalLocal Library!Library! Special Feature on Shinjuku City Libraries Fall in Japan is a very comfortable time of year, and as one saying goes, “Autumn is perfect for reading.” Why not enjoy a few books at the library this fall? Feel free to read, spend time in a relaxing environment, and take advantage of everything else our libraries offer. About Shinjuku City Ochiai Minami- Libraries Nagasaki Shin-Mejiro-dori Ave. Tozai Subway Line Iidabashi There are ten public libraries in Shinjuku City ④Nishi-Ochiai Library ③Tsurumaki Library Kagurazaka with over 882,000 books and more than 48,000 Shimo-Ochiai Takadanobaba DVDs and videos, as well as 65 different news- ①Chuo Library Nishi-Waseda Waseda Ushigome- Meiji-dori Ave. papers and 703 different magazines. Yotsuya Seibu-Shinjuku Line Children’s Library Kagurazaka Nakai ⑤Toyama Library and Okubo Library store more foreign Library Ushigome- ⑦Nakamachi publications than the other libraries, and you Yamanote Line ⑨Okubo Yanagicho Library Library can read magazines and newspapers in various Okubo-dori Ave. Wakamatsu- Ichigaya foreign languages. Kawada -

Takadanobaba, Tokyo, (JP) ! May 2008

! Design Resources > Design Responses > About Parking Facilities > Examples > Transport Interchange Takadanobaba, Tokyo, (JP) ! May 2008 ! ! ! Facility: This is an example of the prevalent type of bicycle parking facility in central Tokyo that requires minimum investment in infrastructure. The bicycle parking service consists of renting public space in designated areas to cyclists. The local administration issues annual or monthly stickers that must go on the bicycle frames; they state the site (street name or number of the facility) within the borough and the expiry date of the subscription. Provider: Shinjuku Ward. Designer/ Architect: Shinjuku transport and roads administration office. Takadanobaba Cycle Rental space Bikeoff Project – Design Against Crime, July 2008 1 ! Cost of Provision: Undisclosed information, but staff member stated its funding is annually included on road marking and road signage budgets of Shinjuku ward. ! ! ! General Description: ! Takadanobaba is a transport hub for commuters travelling in from the west of Tokyo as it is home to three popular train lines: the Seibu Shinjuku Line, the JR Yamanote Line, and the Tozai Line. During the ! morning rush hour, Takadanobaba is one of the hot-spots of the Tokyo transport network with all three stations bursting at the seams with local residents, students and commuters. After the Japanese economic collapse of the late 90’s, bicycle use increased dramatically in Tokyo raising issues of public space occupation. The local governments then started to adapt and redistribute the public space to serve both bicycle users and pedestrians. To discourage the nuisance and accidents caused by bicycles randomly left on the streets, the local governments identified the highest concentrations of bicycles parked around the stations and assigned specific areas.