COMPETITION COMMISSION of INDIA Case No. 39 of 2017 in Re

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Appellate Jurisdiction) IA No.231 Of

I.A. No.231 of 2012 in DFR No.1092 of 2012 Appellate Tribunal for Electricity (Appellate Jurisdiction) I.A. No.231 of 2012 IN DFR No.1092 of 2012 Dated: 20th July, 2012 Present : HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE M KARPAGA VINAYAGAM, CHAIRPERSON HON’BLE MR. RAKESH NATH, TECHNICAL MEMBER In the Matter of: Indian Oil Corporation Ltd. Pipelines Division A-1, Udyog Marg, Sector-1 NOIDA -201 301(U.P) …Appellant/Applicant Versus 1. Gujarat Electricity Regulatory Commission(GERC) 1ST Floor, Neptune Tower Ashram Road, Ahemedabad-380009. 2. Paschim Gujarat Vij Company Ltd., (PGVCL) Registered and Corporate Office at Laxim Nagar, Nana Mava Main Road Rajkot Gujarat – 360 004 Page 1 of 6 I.A. No.231 of 2012 in DFR No.1092 of 2012 3. Uttar Gujarat Vij Company Ltd., (UGVCL), Registerd and Corporate office at Visnagar Road Mehasana – 384 001 4. Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Ltd., (GETCO) Corporate office at Sardar Patel Vidyut Bhawan Race Course Vadodara – 390 007 ...Respondent(s) Counsel for the Appellant(s) : Mr. V.N. Koura Ms. Mona Aneja Counsel for the Respondent(s):- O R D E R PER HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE M. KARPAGA VINAYAGAM, CHAIRPERSON 1. This is an Application filed by the Appellant/Applicant to condone the delay of 715 days in filing the Appeal as against the impugned order dated 13.5.2010. 2. The explanation of this huge delay has been given by the Applicant/Appellant, which is follows:- Page 2 of 6 I.A. No.231 of 2012 in DFR No.1092 of 2012 “ (a) The Applicant filed the Petition No.1004 of 2010 praying for direction to the Distribution Licensee Respondents to pay the applicable tariff to the Applicant as determined by the State Commission. -

Merchants Where Online Debit Card Transactions Can Be Done Using ATM/Debit Card PIN Amazon IRCTC Makemytrip Vodafone Airtel Tata

Merchants where online Debit Card Transactions can be done using ATM/Debit Card PIN Amazon IRCTC Makemytrip Vodafone Airtel Tata Sky Bookmyshow Flipkart Snapdeal icicipruterm Odisha tax Vodafone Bharat Sanchar Nigam Air India Aircel Akbar online Cleartrip Cox and Kings Ezeego one Flipkart Idea cellular MSEDC Ltd M T N L Reliance Tata Docomo Spicejet Airlines Indigo Airlines Adler Tours And Safaris P twentyfourBySevenBooking Abercrombie n Kent India Adani Gas Ltd Aegon Religare Life Insur Apollo General Insurance Aviva Life Insurance Axis Mutual Fund Bajaj Allianz General Ins Bajaj Allianz Life Insura mobik wik Bangalore electricity sup Bharti axa general insura Bharti axa life insurance Bharti axa mutual fund Big tv realiance Croma Birla sunlife mutual fund BNP paribas mutural fund BSES rajdhani power ltd BSES yamuna power ltd Bharat matrimoni Freecharge Hathway private ltd Relinace Citrus payment services l Sistema shyam teleservice Uninor ltd Virgin mobile Chennai metro GSRTC Club mahindra holidays Jet Airways Reliance Mutual Fund India Transact Canara HSBC OBC Life Insu CIGNA TTK Health Insuranc DLF Pramerica Life Insura Edelweiss Tokio Life Insu HDFC General Insurance IDBI Federal Life Insuran IFFCO Tokio General Insur India first life insuranc ING Vysya Life Insurance Kotak Mahindra Old Mutual L and T General Insurance Max Bupa Health Insurance Max Life Insurance PNB Metlife Life Insuranc Reliance Life Insurance Royal Sundaram General In SBI Life Insurance Star Union Daiichi Life TATA AIG general insuranc Universal Sompo General I -

Before the Gujarat Electricity Regulatory Commission

BEFORE THE GUJARAT ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION GANDHINAGAR Petition No 1712 of 2018 In the matter of: Petition under the provision of Electricity Act, 2003 read with GERC (Terms and Conditions of Intra- State Open Access) Regulations, 2011 and in the matter of seeking refund of amount of transmission wheeling charges paid by the Petitioner company Under Protest and in the matter of decision/ order dated 10.05.2017 passed by the Respondent authority rejecting the request/application of refund of amount paid towards Exit Option Charge for Wind Mill No. ADO-36 made by the Petitioner company. Petitioner: Gokul Refoils and Solvent, Gokul House, 43, Shreemali Co-Operative Housing Soc. Ltd., Opp. Shikhar Building, Navrangpura, Ahmedabad. Co-Petitioner: Gokul Agri International Ltd, State Highway No. 41, Near Sujanpur Patia, Sidhpur, District: Patan, Pin Code – 384151 Represented by: Learned Advocate Shri Satyan Thakkar and Shri Nisarg Rawal V/s. Respondent: Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Ltd. Sardar Patel Vidyut Bhavan, Race Course, Vadodara- 390 007. Represented by: Learned Sernior Advocate Shri M. G. Ramchandran with Advocate Ms. Ranjitha Ramchandran and Ms. Venu Birappa CORAM: Shri Anand Kumar, Chairman Shri P. J. Thakkar, Member Date: 09/03/2020 ORDER 1 1 The present petition has been filed by M/s Gokul Refoils & Solvent Limited and M/s Gokul Agri International Limited seeking following prayer: “The Commission may be pleased to quash and set aside the impugned decision/order dated 10.05.2017 passed by the Additional Engineer (R&C), Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Limited and further be pleased to direct the Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Limited i.e. -

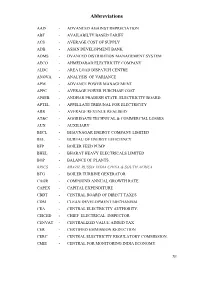

09 List of Abbreviations.Pdf

Abbreviations AAD - ADVANCED AGAINST DEPRECIATION ABT - AVAILABILTY BASED TARIFF ACS - AVERAGE COST OF SUPPLY ADB - ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK ADMS - DVANCED DISTRIBITION MANAGEMENT SYSTEM AECO - AHMEDABAD ELECTRICITY COMPANY ALDC - AREA LOAD DISPATCH CENTRE ANOVA - ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE. APM - ADVANCE POWER MANAGEMENT APPC - AVERAGE POWER PURCHASE COST APSEB - ANDHAR PRADESH STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD. APTEL - APPELLATE TRIBUNAL FOR ELECTRICITY ARR - AVERAGE REVENUE REALISED AT&C - AGGREGATE TECHNICAL & COMMERCIAL LOSSES AUX - AUXILIARY BECL - BHAVNAGAR ENERGY COMPANY LIMITED BEE - BUREAU OF ENERGY EFFICIENCY BFP - BOILER FEED PUMP BHEL - BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LIMITED BOP - BALANCE OF PLANTS. BRICS - BRAZIL RUSSIA INDIA CHINA & SOUTH AFRICA BTG - BOILER TURBINE GENERATOR CAGR - COMPOUND ANNUAL GROWTH RATE CAPEX - CAPITAL EXPENDITURE CBDT - CENTRAL BOARD OF DIRECT TAXES CDM - CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM CEA - CENTRAL ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY. CEICED - CHIEF ELECTRICAL INSPECTOR. CENVAT - CENTRALIZED VALUE ADDED TAX CER - CERTIFIED EMMISSION REDUCTION CERC - CENTRAL ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION. CMIE - CENTRAL FOR MONITORING INDIA ECONOMY. XI CNG - COMPRESSED NATURAL GAS COC - COST OF CAPITAL COD - COMMERCIAL OPERATION DATE COGS - COST OF GOODS SOLD COP - COST OF PRODUCTION CPCB - CENTRAL POLLUTION BOARD CPL - COASTAL POWER LIMITED CPP - CAPTIVE POWER PLANT CPPs - CAPTIVE POWER PLANTS CRISIL - CREDIT RATING INFORMATION SERVICES OF INDIA LIMITED CSS - CROSS SUBSIDY SURCHARGE CST - CENTRAL SALES TAX CTU - CENTRAL TRANSMISSION UTILITY. CVPF -

Presentation (State Updates)

State Updates – Presentations • Andhra Pradesh • Delhi • Gujarat • Haryana • Karnataka • Maharashtra • Tamil Nadu 1 Andhra Pradesh Power Sector Status and Issues Ahead Presentation by People’s Monitoring Group on Electricity Regulation (PMGER) Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh 22nd- 23rd March 2007, Mumbai 1 Reform Milestones 2 1 Reform Milestones in AP APSEB Unbundling Financial autonomy Bulk supply & AP Reforms Unbundled into provided to Discoms. trading vested Bill passed into APGenco / Distribution Citizens charter with Discoms in Assembly APTransco Companies introduced as per EA 2003 Apr’98 Feb’99 Apr’00 Apr’02 June 05’ Tripartite agreement with employees on reform program Feb’97 Mar’99 Oct’02 Dec 05’ Employees 7th ARR & Govt. APERC allocated to Tariff filing policy establish all companies made as statement ed through per ACT issued options 2003 Key statistics 4 2 KEY STATISTICS APTRANSCO & DISCOMs APTRANSCO NPDCL Headquarters HYD Headquarters Warangal Consumers 3.47m ADILABAD SRIKAKULAM NIZAMABAD KARIMNAGAR VIJAYNAGARAM WARANGAL MEDAK VISHAKAPATNAM KHAMMAM EAST RANGAREDDY GODAVARI NALGONDA WEST GODAVARI EPDCL CPDCL MAHABOOB NAGAR KRISHNA GUNTUR Headquarters Vizag Headquarters HYD Consumers 3.57m PRAKASAM Consumers 5.61m KURNOOL BAY OF BENGAL ANANTAPUR NELLORE CUDDAPAH SPDCL CHITTOOR Headquarters Tirupati Consumers 5.20m 5 A snapshot of the AP Power Sector Structure Percentage procured from various Key Statistics of Power Sector in sources AP 49% 33% 14% 4% Total Number of 1.73 Cr APGENCO CGS IPPs / JVs NCEs Consumers Per Capita Consumption -

Uttar Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Well Comes

Uttar Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Well Comes Vibrant Gujarat Global Investors Summit-2007 SUPPLY VOLTAGE Contract Supply Demand Voltage Up to At 11 KV/ 22KV 4000 KVA Above At 66 KV 4000 KVA and above Where to apply for Power Connection Name of DISCOM Name of Districts Madhya Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Vadodara, Anand, Kheda, (MGVCL) Vadodara Panchmahal, Dahod Uttar Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Ahmedabad (except city), (UGVCL) Mehsana Gandhinagar (except city), Mehsana, Banas Kantha, Patan, Sabar Kantha Paschim Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Rajkot, Porbandar, Junagadh, (PGVCL) Rajkot Jamnagar, Kutch, Bhavnagar, Amreli, Surendranagar Dakshin Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Surat except city, Bharuch, (DGVCL) Surat Narmada, Dang,Valsad, Navsari Processing and releasing Authority of HT connection UP TO CIRCLE 275 KVA OFFICE Above CORPORATE 275 KVA OFFICE Procedure for Registration of Application for HT Power Supply Application for supply of power shall be made in the prescribed form. The requisition for supply of electrical energy shall be accompanied by registration charges as under. HT and EHT supply @ Rs.10 per KVA with a ceiling of Rs.25000.00 Checklist- Submission of Documents for Power Supply • Prescribed Application Form in Four (4) Copies • Site plan with key map indicating point of supply in Four (4) Copies. • Land documents – Plot Allotment letter OR 7/12 and 8A Abstract, OR Sale deed in Two (2) Copies. • Memorandum of Articles • Resolution authorizing the person(s) to sign Application and Agreement • Short Description of process • Certificate regarding Industrial use of land from Collector (Before work is taken up on hand.) • NOC of Gujarat Pollution Control Board (Before actual release of power supply.) Estimate [1] • On registration of demand, the DISCOM shall furnish an estimate including Security Deposit and charges for providing electric line/infrastructure as per technical feasibility report. -

Biller Name Adani

Biller Name Adani Gas - Gujarat Adani Gas - Haryana BSES Rajdhani Power Limited BSES Yamuna Power Limited Connect Broadband Delhi Jal Board India Power Corporation - Bihar India Power Corporation - West Bengal Jamshedpur Utilities Maharashtra State Electricity Distbn Co Ltd Mahanagar Gas Limited Meghalaya Power Dist Corp Ltd M.P. Paschim Kshetra Vidyut Vitaran MTNL Mumbai Noida Power Reliance Energy Siti Energy - Delhi Siti Energy - Haryana Siti Energy - Uttar Pradesh Tata Power - Delhi Tikona Digital Networks Private Limited Torrent Power - Agra Torrent Power - Ahmedabad Torrent Power - Bhiwandi Torrent Power - Surat Tripura Electricity Corp Ltd Uttarakhand Jal Sansthan Uttarakhand Power Corporation Limited Muzaffarpur Vidyut Vitran Limited SNDL Nagpur Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation (CESC) BSNL Landline - Corporate BSNL Landline - Individual BSNL Mobile Postpaid Aircel Postpaid Gujarat Gas Limited NESCO, Odisha SOUTHCO, Odisha Urban Improvement Trust (UIT) - Bhiwadi Kota Electricity Distribution Limited (KEDL) Tripura Natural Gas Municipal Corporation of Gurugram Reliance Postpaid Eastern Power Distribution Co Ltd (APEPDCL) Southern Power Distribution Co Ltd (APSPDCL) Bharatpur Electricity Services Ltd. (BESL) Jaipur Vidyut Vitran Nigam (JVVNL) Uttar Pradesh Power Corp Ltd (UPPCL) - URBAN Daman and Diu Electricity Indraprastha Gas Bikaner Electricity Supply Limited (BkESL) Haryana City Gas Sabarmati Gas Limited (SGL) Tata Power - Mumbai TP Ajmer Distribution Ltd (TPADL) ACT Broadband AIRCEL POSTPAID Airtel Landline AIRTEL POSTPAID -

Energy News Monitor

June 24, 2016, Volume XIII, Issue 2 Energy News Monitor NATIONAL: OIL & GAS Upstream IOC-led consortium buys 24 percent stake in to May, covering a total of 31 MODUs on the west coast Russian oil field and 2 on the east coast and placing each on its respective monsoon location before the onset of the seasonal June 18, 2016. A consortium led by Indian Oil Corp adverse weather conditions. (www.rigzone.com) (IOC) oil companies IOC, BPCL and OIL signed an agreement to buy 23.9% stake in Russia's Vankor oil field Downstream from Rosneft for $2.1 billion, IOC said. ONGC Videsh RIL, IIP develop technology to reduce benzene Ltd (OVL) has recently picked up 15% stake in the levels Vankor fields for $1.27 billion. IOC and OIL will pick up 8% stake each while the remaining 7.8% stake will go to June 20, 2016. Reliance Industries Ltd (RIL) in a BRPL. The recoverable resources of the Vankor field collaboration with Indian Institute of Petroleum (IIP) stood at 361 million tonnes of oil and condensate and 138 Dehradun has developed an indigenous technology to billion cubic metres of gas. (www.business-standard.com) restrict benzene, a carcinogenic element in gasoline and naphtha. RIL carried out the construction and the ONGC sets new pre-monsoon rig move offshore 'flawless' commissioning of the Benzene Recovery Unit India (BRU). The company said that there has been an June 17, 2016. Oil and Natural Gas Corp (ONGC) has, increasing pressure on refiners around the world to with the support of Norway's Aqualis Offshore, set a new reduce the amount of benzene and other hazardous air pre-monsoon rig move record offshore India recently pollutants in the gasoline pool because of health and that involved 33 mobile offshore drilling units (MODU). -

Gujarat's Electricity Sector Transformation

Tim Buckley, Director for Energy Finance Studies, Australasia 1 Kashish Shah, Research Analyst August 2019 Gujarat’s Electricity Sector Transformation A Role Model of India’s Electricity Transition Executive Summary GUJARAT, LOCATED ON THE WESTERN COAST OF INDIA, IS AN ECONOMIC POWERHOUSE that contributed roughly 8% of India’s total gross domestic product (GDP) between 2011/12 and 2018/19. It is one of the most industrially focussed states in India, with three quarters of Gujarat’s state GDP coming from the industrial sector. IEEFA also identifies Gujarat as one of the five leading Indian states for renewable energy in terms of both existing generation capacity as well as future potential. There was 2 gigawatt (GW) of solar power capacity, 6GW of wind power capacity and 0.5GW of biomass capacity operational as of March 2019. India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) estimates Gujarat’s renewables potential to be 72.7GW, equally balanced between solar and wind energy potential. This includes the 5GW Dholera Solar Park, the largest proposed solar development in the world to-date. August 2019 saw NTPC announce plans for another 5GW of solar park at Kutch in Gujarat during its annual investor meet for FY2018/19. This announcement puts Gujarat ahead in the race for building renewables capacity between states such as Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan with similar renewable energy potential. GUJARAT’S CURRENT ELECTRICITY MIX IS DOMINATED BY THERMAL POWER SOURCES. The 22.3GW of thermal capacity comprises 15.8GW of coal-fired and 6.6GW of gas-fired capacity. -

Biller Category Location Aavantika Gas Ltd. Gas Madhya Pradesh ACT

Biller Category Location Aavantika Gas Ltd. Gas Madhya Pradesh ACT Fibernet Broadband Postpaid National Adani Electricity Mumbai Limited Electricity Mumbai Adani Gas Gas National Adani Gas Gas National Aegon Life Insurance Company Limited Insurance National Airtel Broadband Broadband Postpaid National Airtel DTH Recharge DTH National Airtel Landline Broadband Postpaid National Airtel Postpaid Mobile Postpaid National Airtel Prepaid Mobile Prepaid National Ajmer Vidyut Vitran Nigam Limited Electricity Rajasthan Assam Power Distribution Company Ltd (NON-RAPDR) Electricity Assam Assam Power Distribution Company Ltd (RAPDR) Electricity Assam Aviva Life Insurance Company Limited Insurance National Bajaj Allianz Life Insurance Company Limited Insurance National Bangalore Electricity Supply Co. Ltd (BESCOM) Electricity Bangalore Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board Water Bengaluru Brihan Mumbai Electric Supply and Transport Undertaking Electricity Mumbai Bharatpur Electricity Services Ltd. (BESL) Electricity Rajasthan Bikaner Electricity Supply Limited (BkESL) Electricity Rajasthan Aditya Birla Sun Life Insurance Company Ltd Insurance National BSES Rajdhani Power Limted Electricity Delhi BSES Yamuna Power Limited Electricity Delhi Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited - Landline Individual Landline Postpaid National Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited - Mobile Postpaid Mobile Postpaid National Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited - Prepaid DTH National Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation Electricity Kolkata Cancer Patients Aid Association Limited Donation National -

At Gandhinagar

BEFORE THE GUJARAT ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION AT GANDHINAGAR PETITION NO. 1363 of 2013 In the matter of: Petition under Section 86(1)(a), 86 (1)(b), 86 (1)(e) and 86 (1)(f) read with Sections 61(h) and 62(1)(a) of the Electricity Act, 2003 for direction of the Commission to the Respondent to comply with the Provisions of the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (Terms & Conditions for Recognition and issuance of Renewable Energy Certificate for Renewable Energy Generation) Regulations, 2010 dated 14.1.2010 and Gujarat Electricity Regulatory Commission (Procurement of Energy from Renewable Sources) Regulations, 2010 dated 17.4.2010. Petitioners : 1. Renew Wind Energy (Rajkot) Private Limited Registered Office at 138, Ansal Chamber-II,Bikaji Cama Place, New Delhi-110066. 2. Wind Independent Power Producers Association, 6th Floor, Block 4-A, DLF Corporate Park, Mahrauli-Gurgaon Road, Gurgaon-122002. Represented by : Learned Advocate Shri Vishal Gupta with Shri P. K. Mishra for Petitioner No.1. V/s. Respondents : 1. Gujarat Urja Vikas Nigam Ltd (GUVNL) Page | 1 Sardar Patel Vidyut Bhavan, Race Course, Vadodara – 390024. 2. Madhya Gujarat Vij Company Limited (MGVCL) Vadodara. 3. Uttar Gujarat Vij Company Limited (UGVCL) Mehsana. 4. Paschim Gujarat Vij Company Limited (PGVCL) Rajkot. 5. Dakshin Gujarat Vij Company Limited (DGVCL) Surat. Represented by (1) Learned Advocate Shri M. G. Ramachandran. with S/Shri K.P.Jangid and V.T. Patel for GUVNL. (2) Shri M. L. Rabari, for MGVCL. (3) Shri R. P. Raval and Shri V. A. Patel, for UGVCL. (4) Shri J.J.Gandhi, for the PGVCL. (5) Shri B.V. -

Uttar Gujarat Vij Company Limited (UGVCL)

CRISIL Risk and Infrastructure Solutions Limited Uttar Gujarat Vij Company Limited (UGVCL ) Category Wise Cost of Service Study for FY 2011-12 Final Report December 2012 Consultant Team Project Leader Project Manager Analyst Team Leader Associate [ii ] Abbreviations A&G : Administrative and General Expenses CoS : Cost of Service DGVCL : Dakshin Gujarat Vij Company Limited DISCOM : Distribution Company EA 2003 : Electricity Act, 2003 FY : Financial Year GERC : Gujarat Electricity Regulatory Commission GFA : Gross Fixed Assets GoG : Government of Gujarat GUVNL : Gujarat Urja Vij Nigam Limited HT : High Tension JGY : Jyoti Gram Yojana LT : Low Tension MGVCL : Madhya Gujarat Vij Company Limited MU : Million Unit MW : Mega Watt O&M : Operation & Maintenance PGVCL : Paschim Gujarat Vij Company Limited PSL : Public Street Lighting PWW : Public Water Works RoE : Return on Equity R&M : Repairs & Maintenance UGVCL : Uttar Gujarat Vij Company Limited [iii ] Contents 1. Background .................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Objective ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 3. Basic Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ 5 3.1 Classification of Costs ...........................................................................................................................