Volume 73: 4 Summer 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC DRAFT MAY 2019 Was Created By

PUBLIC DRAFT MAY 2019 was created by: MISSOULA DOWNTOWN ASSOCIATION BUSINESS IMPROVEMENT DISTRICT MISSOULA DOWNTOWN FOUNDATION The Downtown Missoula Partnership Dover, Kohl & Partners a collaboration of: planning team lead | town planning & urban design The Downtown Business Improvement District of Missoula Six Pony Hitch branding and outreach Missoula Downtown Association Territorial Landworks Missoula Downtown Foundation infrastructure Other major partners on this project include: Kimley Horn parking Missoula Redevelopment Agency Charlier Associates, Inc. Missoula Parking Commission transportation City of Missoula Cascadia Partners scenario planning Gibbs Planning Group retail market analysis Daedalus Advisory Services economics Urban Advantage photo simulations ... and thousands of participants from the Missoula community! Missoula’s Downtown Master Plan | Draft Steering Committee Our thanks to the following leaders who guided this process through the Master Plan Steering Committee and Technical Advisory Committee: Ellen Buchanan, Chair, Missoula Redevelopment Mike Haynes, Development Services Director Agency Donna Gaukler, Missoula Parks & Recreation Director Matt Ellis, Co-Chair, MDA & MPC Board Member Jim McLeod, Farran Realty Partners Owner Dale Bickell, City Chief Administrative Officer Eran Pehan, Housing & Community Development Dan Cederberg, Property Owner; BID Board, MDF Director Board Dave Strohmaier, Missoula County Commissioner Nick Checota, Property/Business Owner; Arts & Bryan Von Lossberg, Missoula City Council Entertainment -

Interpretive Plan

MISSOULA DOWNTOWN HERITAGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN DRAFT - NOVEMBER 2019 Prepared for the Missoula In collaboration with the City of Missoula Historic Preservation Downtown Foundation by Office and Downtown Missoula Partnership. Supported by a Historical Research Associates, Inc. grant from the Montana Department of Commerce Missoula public art. Credit: HRA TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 5 PART 1: FOUNDATION . 13 Purpose and Guiding Principles . 14 Interpretive Goals . 15 Themes . 15 Interpretive Theme Matrices . 19 Setting and Audiences . 23 Issues and Influences Affecting Interpretation . 24 PART 2: EXISTING CONDITIONS . 26 Interpretation in Downtown Missoula . 27 Information and Orientation . 28 Audience Experience . 29 Programming . 31 Potential Partners . 32 PART 3: RECOMMENDATIONS . 37 Introduction . 38 Actions Related to the Connectivity of Downtown Interpretation . 38 Actions Related to Special Events . 41 Actions Related to the Missoula Downtown Master Plan . 41 Actions Related to Pre-Visit/Distance Interpretation . 42 Actions Related to Interpreting Many Perspectives and Underrepresented Heritage . 44 Actions Related to Audience Experience . 47 Actions Related to Program Administration . 51 Actions Related to Scholarship . 51 Actions Related to Additional Interpretative Elements . 52 Actions Related to Collaboration . 52 Actions Related to Educators and Youth Outreach . 54 Actions Related to General Outreach and Marketing . 54 Recommended Implementation Plan . 55 Summary . 69 PART 4: PLANNING RESOURCES . 70 HRA Interpretive Planning Team . 71 Interpretive Planning Advisory Group . 71 Acknowledgements . 71 Glossary . 71 Select Interpretation Resources . 72 Select Topical Resources . 72 INTRODUCTION Downtown heritage mural interpreting local railroad history. Credit: HRA Missoula Downtown Heritage | Interpretive Plan | DRAFT Nov 2019 5 Missoula Textile is a Downtown Missoula heritage business, having been in operation for more than 100 years. -

Academic & Student Affairs Committee

Schedule of Events Board of Regents Meeting May 2006 WEB PAGE ADDRESS: http://www.montana.edu/wwwbor/ WEDNESDAY, May 31, 2006 1:00 – 4:30 p.m. Budget and Audit Oversight Committee – SUB Ballroom 1:00 – 4:30 p.m. Academic/Student Affairs Committee – Hensler Auditorium, Applied Technology Building 4:45 – 6:00 p.m. Staff and Compensation Committee – SUB Ballroom 4:45 – 6:00 p.m. Workforce Development Committee – Hensler Auditorium, Applied Technology Building THURSDAY, June 1, 2006 7:00 a.m. Regents Breakfast with Faculty Senate Representatives - Crowley Conference Room - 2nd floor of SUB 7:45 a.m. Continental Breakfast for meeting participants—– SUB Large Dining Room 8:15 a.m. Executive Session (Personnel Evaluations) – Crowley Conference Room – 2nd floor SUB 10:00 a.m. Full Board Convenes– SUB Ballroom Noon Lunch for all attendees – SUB Large Dining Room Noon to 1:40 p.m. MAS Luncheon with Regents, Commissioner, Presidents and Chancellors — SUB Ballroom 1:30 p.m. Full Board Reconvenes– SUB Ballroom 5:30 p.m. Board Recesses 6:00 p.m. Reception for all meeting participants – Pitchfork Fondue Dinner - in the new ATC Center FRIDAY, June 2, 2006 7:00 a.m. Board breakfast with local civic and business leaders – SUB Large Dining Room 7:45 a.m. Continental Breakfast for meeting participants – SUB Large Dining Room 8:45 a.m. Full Board Reconvenes– SUB Ballroom 12:00 Meeting Adjourns on completion of business 1 Board of Regents’ Regular Meeting–May 31-June 2, 2006–HAVRE 5/19/2006 10:28 AM Page 1 BOARD OF REGENTS OF HIGHER EDUCATION May 31 – June 2, 2006 Montana State University-Northern P.O. -

Christopher P Higgins

Missoula Mayors Interred at The Missoula Cemetery 2 3 This booklet was compiled and printed by the Missoula Cemetery as an informational booklet for individual use. The Missoula Cemetery is a department of the City of Missoula in Missoula, Montana. Questions and comments should be directed to: Missoula Cemetery 2000 Cemetery Road Missoula Montana 59802 Phone: (406) 552-6070 Fax: (406) 327-2173 Web: www.ci.missoula.mt.us/cemetery Visit our website for a complete interment listing, historical information, fees, cemetery information, and regulations. © 2008 Missoula Cemetery 4 Table of Contents Timeline: Mayors and Local History ................................................................................................ 6 Map: Mayors Burial Sites ................................................................................................................ 8 Frank Woody .................................................................................................................................. 10 Thomas Marshall ............................................................................................................................ 11 Dwight Harding ............................................................................................................................... 12 David Bogart ................................................................................................................................... 13 John Sloane ................................................................................................................................... -

Connections December 2013

December 2013 A biannual newsletter published by the Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library A Message from the Dean of Libraries hen I started writing this message, this opportunity to thank the members of I looked outside and saw snow the project review taskforce who issued an falling that quickly covered open call for projects, reviewed all proposals Mount Sentinel. Nonetheless, in the midst of according to established criteria, and selected my second winter in Montana, I have been the best proposals for action. A big thank-you warmed by the high level of enthusiasm and also goes to all team members who conducted energy from library faculty, staff, and generous user needs assessments, prepared their donors. Their dedication and unwavering proposals, submitted and carried out their support have helped us move forward on plans. They have indeed implemented many many fronts this past year. innovative ideas to enhance UM students’ learning experience. In this issue of Connections, the Mansfield Library’s newsletter, we present reports on The library’s generous donors have played the library’s Student-Centered Innovative an important role this year by supporting Projects. As its name conveys, these projects enhancement and expansion of the library’s focus on supporting UM students’ success collections, including archival materials and in their educational pursuits. I want to take special collections, funding improvements continued on page 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA Learning Commons at the Maureen and Mike * Mansfield Library jjtt .L ’ The Learning Commons is an integral part of UM's Investing . in Student Success. Of the university's current priorities, the Learning Commons will have the most meaningful and dramatic impact on the greatest number of UM students. -

SNMIPNUNTN Nmipnuntn a Salish Word Meaning ~A Place to Learn, S a Place to Figure Things Out, a Place Where Reality Is Discovered~ VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 SEPTEMBER 2012

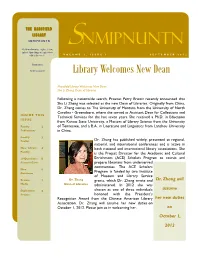

THE MANSFIELD LIBRARY SNMIPNUNTN nmipnunTn A Salish word meaning ~a place to learn, s a place to figure things out, a place where reality is discovered~ VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 SEPTEMBER 2012 Pronunciation: Sin-mee-pi-noon-tin Library Welcomes New Dean Mansfield Library Welcomes New Dean Sha Li Zhang, Dean of Libraries Following a nationwide search, Provost Perry Brown recently announced that Sha Li Zhang was selected as the new Dean of Libraries. Originally from China, Dr. Zhang comes to The University of Montana from the University of North Carolina - Greensboro, where she served as Assistant Dean for Collections and INSIDE THIS Technical Services for the last seven years. She received a Ph.D. in Education ISSUE: from Kansas State University, a Masters of Library Science from the University Faculty 2 of Tennessee, and a B.A. in Literature and Linguistics from Lanzhou University Publications in China. Faculty 3 Profile Dr. Zhang has published widely, presented at regional, national, and international conferences and is active in New Library 4 both national and international library associations. She Faculty is the Project Director for the Academic and Cultural 10 Questions - 5 Enrichment (ACE) Scholars Program to recruit and Susanne Caro prepare librarians from underserved communities. The ACE Scholars New 6 Databases Program is funded by two Institute of Museum and Library Service Browse 7 Dr. Zhang grants, which Dr. Zhang wrote and Dr. Zhang will Media Dean of Libraries administered. In 2012 she was assume Digitization 8 chosen as one of three individuals Project honored with the President’s Recognition Award from the Chinese American Library her new duties Association. -

Children's Television. Hearing on H.R. 1677 Before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Finance of the Committee on Energy and Commerce

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 315 048 IR 014 159 TITLE Children's Television. Hearing on H.R. 1677 before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Finance of the Committee on Energy and Commerce. House of Representatives, One Hundred First Congress, First Session. INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Energy and Commerce. PUB DATE 6 Apr 89 NOTE 213p.; Serial No. 101-32. AVAILABLE FROMSuperintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Mat.. als (090) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Childrens Television; *Federal Legislation; Hearings; *Programing (Broadcast); *Television Commercials IDENTIFIERS Congress 101st ABSTRACT A statement by the chairman of the subcommittee, Representative Edward J. Markey opened this hearing on H.R. 1677, the Children's Television Act of 1989, a bill which would require the Federal Communications Commission to reinstate restrictions on advertising during children's television, to enforce the obligation of broadcasters to meet the eduCational and informational needs of the child audience, and for other purposes. The text of the bill is then presented, followed by related literature, surveys, and the testimony of nine witnesses: (1) Daniel R. Anderson, Psychology Department, University of Massachusetts; (2) Helen L. Boehm, vice president, Children's Advertising Review Unit, Council of Better Business Bureaus, Inc.;(3) Honorable Terry L. Bruce, Representative in Congress from the State of Illinois;(4) William P. Castleman, vice president, ACT III Broadcasting, on behalf of the Association of Independent Television Stations;(5) Peggy Charren, president, Action for Children's Television; (6) DeWitt F. -

Level O (27/28)

Level O (27/28) Title Author A Picture Book of Benjamin Franklin David Adler Aldo Ice Cream Johanna Hurwitz Aldo Peanut Butter Johanna Hurwitz Alexander Books Judith Viorst Ali Baba Bernstein, Lost and Found Johanna Hurwitz Almost Starring Skinnybones Barbara Park An Angel for Solomon Singer Cynthia Rylant Angel’s Mother’s Boyfriend Judy Delton Baby Sitters Club Ann Martin Backyard Angel Judy Delton Baseball Fever Johanna Hurwitz Baseball Saved Us Ken Mochizuki Beezus and Ramona Beverly Cleary Brown Sunshine of Sawdust Valley Marguerite Henry Chocolate Fever Robert Smith Class Clown Johanna Hurwitz Class President Johanna Hurwitz Clue Jr. Parker Hinter Fire! Fire! Angela Medearis Flossie & the Fox Pat McKissack Give Me Back My Pony Jeanne Betancourt Going West Jean Van Leeuwen Happily Ever After Anna Quindlen Harriet’s Hare Dick King-Smith Haunting of Grade Three Grace MacCarone Hawk, I’m Your Brother Gail Gibbons Hello, Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle Betty MacDonald Henry and Beezus Beverly Cleary Henry and Ribsy Beverly Cleary Henry and the Clubhouse Beverly Cleary Henry and the Paper Route Beverly Cleary Henry Huggins Beverly Cleary Hurray for Ali Baba Bernstein Johanna Hurwitz I Love You the Purplest Barbara Joosse Just Grace and the Double Surprise Charise Harper Just Grace and the Snack Attack Charise Harper Just Grace Goes Green Charise Harper Just Tell Me When We’re Dead! Eth Clifford Liar, Liar, Pants on Fire Gordon Korman Llama in the Family Johanna Hurwitz Look Out! Washington D.C. Patricia Giff Make a Wish, Molly Barbara Cohen Meg Mackintosh Series Lucinda Landon Mitch and Amy Beverly Cleary Mouse Magic Ben Baglio Mrs. -

Missoula Attractions Hand-Carved Carousels in the United States

27 DOWNTOWN RESERVE STREET BUSINESS DISTRICT Home to a plethora of big box stores, chain 31 A CAROUSEL FOR MISSOULA restaurants and nationally branded hotels. Fastest carousel in the West and one of the first fully Missoula Attractions hand-carved carousels in the United States. 28 HUB FAMILY ENTERTAINMENT CENTER Go-karts, arcade games and laser tag on 50,000 square 32 DRAGON HOLLOW PLAYGROUND feet of fun and excitement for the whole family. Magical play land next to A Carousel for Missoula. Recently expanded for children of all abilities. 29 MUSEUM OF MOUNTAIN FLYING Showcasing the region’s mountain flying history 33 MISSOULA ART MUSEUM including vintage aircraft, memorabilia and artifacts. Leading contemporary art museum featuring 30 MISSOULA MONTANA AIRPORT Montanan and indigenous exhibits. Free admission for all. Offering nonstop flights to 16 major U.S. markets on six airlines and connecting you to the world. 34 HIKING + BIKING 15 MISSOULA COUNTY FAIRGROUNDS ZOOTOWN ARTS COMMUNITY CENTER A local arts center with exhibits, galleries, 1 Home to the Western Montana Fair and Glacier Ice WATERWORKS HILL TRAILHEAD Rink and host of events year-round. performances, events and paint-your-own pottery. Located just off Greenough Drive, Waterworks Hill is 35 an easy, scenic in-town hike. 16 GLACIER ICE RINK CARAS PARK Located in the heart of downtown. Host to markets 2 Offering programs for youth hockey, adult hockey, FROEHLICH TRAILHEAD figure skating, curling and public skating. and events throughout the year. Froehlich Trail and Ridge Trail Loop form a 36 moderately difficult loop for hiking and running. 17 FORT MISSOULA REGIONAL PARK THE WILMA State-of-the-art concert venue with all the character 3 Sports complex with a fitness center and 156 acres of LINCOLNWOOD TRAILHEAD playgrounds, fields, picnic shelters and trails. -

June 2017 News Releases

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present University Relations 6-1-2017 June 2017 news releases University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations, "June 2017 news releases" (2017). University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present. 22202. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases/22202 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Relations at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - UM News - University Of Montana A to Z my.umt.edu UM News UM / News / 2017 / June June 2017 News 06/30/2017 - Butte Folk Festival Acts Named for Montana Public Radio Live Broadcast - Michael Marsolek 06/29/2017 - UM, Wildlife Friendly Enterprise Network Launch Elephant-Friendly Tea - Lisa Mills 06/29/2017 - Last Best Conference Returns to Missoula, Adds Live Music, Film to Lineup - Peter Knox 06/29/2017 - MTPR Website, Program Receive Statewide Recognition - Ray Ekness 06/28/2017 - UM Research: Slow-Growing Ponderosas Survive Mountain Pine Beetle Outbreaks - Anna Sala 06/27/2017 - SpectrUM, SciNation -

Straight Talk 03.2006

News For And About The Libraries Of Northeast Nebraska MARCH, 2006 - Published by the Northeast Library System Kathy Ellerton - System Administrator/Editor National D.E.A.R. Day April 12, 2006 has been proclaimed National “Drop Everything and Read” Day! The National Education Association (NEA), National Parent Teacher Association (PTA), The Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC), a division of the American Library Association, Reading Rockets and HarperCollins Children’s Books today announced a Spring 2006 partnership to establish a nationwide initiative encouraging families to designate a special time to “drop everything and read.” On April 12th, families are asked to take at least 30 minutes to put aside all distractions and enjoy books together. The 90th birthday of beloved Newbery Medal-winning author Beverly Cleary is the official date for National “Drop Everything and Read” Day, and Cleary’s most popular children’s book character, Ramona Quimby, is the program’s official spokes- person (the concept of “Drop Everything and Read” or D.E.A.R. is referenced in the second chapter of Ramona Quimby, Age 8). Ramona’s encounter with D.E.A.R. time in Ramona Quimby, Age 8 was inspired by letters Beverly Cleary received from children who participated in “Drop Everything and Read” activities themselves. Their interest and enthusiasm for this unique reading program inspired Mrs. Cleary to provide the same experience to Ramona, who enjoys D.E.A.R. time with the rest of her class. Like Ramona, kids enjoy D.E.A.R. (sometimes also known as D.I.R.T., S.S.R., U.S.S.R., S.Q.U.I.R.T., F.V.R. -

Downtown Missoula Venues 2017

Downtown Missoula Venues 2017 Caras Park Burns Street Center Rental Fee ........................... Monday-Thursday: $700; Friday-Sunday: $975 Rental Fee ................................................ Neighborhood Organization: Free, .................................................................. $100 Discount for MDA members .......................... Non-profit Organization: $20/hour, Private Parties: $35/hour Capacity for a Reception/Meeting ......................................................... 3,000 Deposit……………………………………………………. …$100 returnable fee Capacity for a Sit Down Dinner ................................................................ 450 Capacity for a Sit Down Event .................................................................... 80 ADA Accessibility ..................................................................................... Yes ADA Accessibility ..................................................................................... Yes Catering Restrictions ..................................................................................No Catering Restrictions ................................................................................. No Alcohol ..................................................................................................... Yes Alcohol ..................................................................................................... Yes Additional Info ....... Outdoor facility available from mid-April through October Additional Info ...................... Semi-private: