Double Talon Cusps on Supernumerary Tooth Fused to Maxillary Central Incisor: Review of Literature and Report of Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary for Narrative Writing

Periodontal Assessment and Treatment Planning Gingival description Color: o pink o erythematous o cyanotic o racial pigmentation o metallic pigmentation o uniformity Contour: o recession o clefts o enlarged papillae o cratered papillae o blunted papillae o highly rolled o bulbous o knife-edged o scalloped o stippled Consistency: o firm o edematous o hyperplastic o fibrotic Band of gingiva: o amount o quality o location o treatability Bleeding tendency: o sulcus base, lining o gingival margins Suppuration Sinus tract formation Pocket depths Pseudopockets Frena Pain Other pathology Dental Description Defective restorations: o overhangs o open contacts o poor contours Fractured cusps 1 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 Caries Deposits: o Type . plaque . calculus . stain . matera alba o Location . supragingival . subgingival o Severity . mild . moderate . severe Wear facets Percussion sensitivity Tooth vitality Attrition, erosion, abrasion Occlusal plane level Occlusion findings Furcations Mobility Fremitus Radiographic findings Film dates Crown:root ratio Amount of bone loss o horizontal; vertical o localized; generalized Root length and shape Overhangs Bulbous crowns Fenestrations Dehiscences Tooth resorption Retained root tips Impacted teeth Root proximities Tilted teeth Radiolucencies/opacities Etiologic factors Local: o plaque o calculus o overhangs 2 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 o orthodontic apparatus o open margins o open contacts o improper -

Case Report Talon Cusp Type I: Restorative Management

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Dentistry Volume 2015, Article ID 425979, 5 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/425979 Case Report Talon Cusp Type I: Restorative Management Rafael Alberto dos Santos Maia,1 Wanessa Christine de Souza-Zaroni,2 Raul Sampaio Mei,3 and Fernando Lamers2 1 Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, HGU, University of Cuiaba,´ 78016-000 Cuiaba,´ MT, Brazil 2School of Dentistry, Cruzeiro do Sul University (UNICSUL), 08060-070 Sao˜ Paulo, SP, Brazil 3School of Dentistry, University Center of Grande Dourados (UNIGRAN), 79824-900 Dourados, MS, Brazil Correspondence should be addressed to Wanessa Christine de Souza-Zaroni; [email protected] Received 9 February 2015; Accepted 15 April 2015 Academic Editor: Carla Evans Copyright © 2015 Rafael Alberto dos Santos Maia et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The teeth are formed during intrauterine life (i.e., gestation) during the odontogenesis stage. During this period, the teeth move until they enter the oral cavity. This course covers various stages of dental development, namely, initiation, proliferation, histodif- ferentiation, morphodifferentiation, and apposition. The talon cusp is an anomaly that occurs during morphodifferentiation, and this anomaly may have numerous adverse clinical effects on oral health. The objective of this study was to report a case of “Talon Cusp Type I” and to discuss diagnostic methods, treatment options for this anomaly, and the importance of knowledge of this morphological change among dental professionals so that it is not confused with other morphological changes; such knowledge is required to avoid unnecessary surgical procedures, to perform treatments that prevent caries and malocclusions as well as enhancing aesthetics, and to improve the oral health and quality of life of the patient. -

Talon Cusp: a Case Report and Literature Review 1R Kalpana, 2M Thubashini

OMPJ R Kalpana, M Thubashini 10.5005/jp-journals-10037-1045 CASE REPORT Talon Cusp: A Case Report and Literature Review 1R Kalpana, 2M Thubashini ABSTRACT The prevalence of talon cusp varies with race, age, Talon cusp is a well‑delineated accessory cusp thought to and the criteria used to define this abnormality. A review arise as a result of evagination on the surface of a tooth before of the literature suggests that 75% of the cases are in the calcification has occurred. It is seen projecting from the cin permanent dentition and 25% in the primary dentition. gulum or cementoenamel junction of maxillary or mandibular anterior tooth. It is named due to its resemblance to eagle’s This anomaly has a greater predilection in the maxilla talon, which is the shape of eagle’s claw when hooked on to its (with more than 90% of the cases reported) than in the prey. The incidence is 0.04 to 8%. This article reports a case mandible (only 10% of the cases).7 In the permanent denti- of talon cusp on maxillary permanent lateral incisor. When it occurs on the facial aspect, the effects are mainly esthetic and tion, 55% of the cases involved maxillary lateral incisors, 4,8 functional and so early detection and treatment is essential in 33% involved central incisors and 4% involved canines. its management to avoid complications. The purpose of this article is to report a case of palatal Keywords: Talon cusp, Evagination, Maxillary lateral incisor. talon cusp on the permanent maxillary lateral incisor How to cite this article: Kalpana R, Thubashini M. -

Molar-Incisor Hypomineralization and Delayed Tooth Eruption

Winter 2017, Volume 6, Number 4 Case Report: Mandibular Talon Cusp Associated With Molar-Incisor Hypomineralization and Delayed Tooth Eruption ٭Katayoun Salem1 , Fatemeh Moazami2, Seyede Niloofar Banijamali3 1. Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Dental Branch of Tehran, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. 2. Pedodontist, Tehran, Iran. 3. Postgraduate Student, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Dental Branch of Tehran, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. Use your device to scan and read the article online Citation: Salem K, Moazami F, Banijamali SN. Mandibular Talon Cusp Associated With Molar-Incisor Hypomineralization and Delayed Tooth Eruption. Journal of Dentomaxillofacial Radiology, Pathology and Surgery. 2017; 6(4):141-145. : http://dx.doi.org/10.32598/3dj.6.4.141 Funding: See Page 144 Copyright: The Author(s) A B S T R A C T Talon cusp is an odontogenic anomaly in anterior teeth, caused by hyperactivity of enamel Article info: in morphodifferentiation stage. Talon cusp is an additional cusp with several types based on Received: 25 Aug 2017 its extension and shape. It has enamel, dentin, and sometimes pulp tissue. Moreover, it can Accepted: 20 Nov 2017 cause clinical problems such as poor aesthetic, dental caries, attrition, occlusal interferences, Available Online: 01 Dec 2017 and periodontal diseases. Therefore, early diagnosis and effective treatment of talon cusp are essential. Maxillary incisors are the most commonly affected teeth. However, occurrence of mandibular talon cusp is a rare entity. We report a talon cusp in the lingual surface of the permanent mandibular left central incisor, in a 7-year-old Iranian boy. To our knowledge it is Keywords: the third case reported in Iranian patients. -

Prevalence of Dental Anomalies in Indonesian Individuals with Down Syndrome

Pesquisa Brasileira em Odontopediatria e Clínica Integrada 2019; 19:e5332 DOI: http://doi.org/10.4034/PBOCI.2019.191.147 ISSN 1519-0501 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Prevalence of Dental Anomalies in Indonesian Individuals with Down Syndrome Luly Anggraini1, Mochamad Fahlevi Rizal2, Ike Siti Indiarti3 1Faculty of Dentistry, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta Pusat, Indonesia. 0000-0002-9018-8873 2Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta Pusat, Indonesia. 0000-0001-6654-7744 3Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta Pusat, Indonesia. 0000-0001-6776-912X Author to whom correspondence should be addressed: Mochamad Fahlevi Rizal, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Universitas Indonesia, Jalan Salemba Raya No.4, Jakarta Pusat, Jakarta 10430, Indonesia. Phone: +62 81311283838. E-mail: [email protected]. Academic Editors: Alessandro Leite Cavalcanti and Wilton Wilney Nascimento Padilha Received: 24 April 2019 / Accepted: 27 September 2019 / Published: 16 October 2019 Abstract Objective: To determine the frequency distribution of dental anomalies in people with Down syndrome. Material and Methods: This cross-sectional study was developed in Jakarta, Indonesia, and evaluated 174 individuals with Down syndrome aged 14-53 years. Were collected information regarding the tooth number, tooth size, shape, and structure. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the absolute and relative frequencies. The Pearson chi-square test was used in bivariate analysis. The significance threshold was set at 5%. Results: There were 70 female subjects (40.2%) and 104 male subjects (59.8%) with an average age of 19.2 years. In terms of anomalies of tooth number, hypodontia (80.9%), supernumerary teeth (12.4%), and combined hypodontia and supernumerary teeth (12.4%) were identified. -

Dens Evaginatus of Anterior Teeth (Talon Cusp): Report of Five Cases

Restorative Dentistry Dens evaginatus of anterior teeth (talon cusp): Report of five cases Juan J. Segura-Egea, DDS, MD, PhD1/Alicia Jiménez-Rubio, DDS, MD, PhD2/ José V. Ríos-Santos, DDS, MD, PhD3/Eugenio Velasco-Ortega, DDS, MD, PhD3 The talon cusp, or Dens evaginatus of anterior teeth, is a relatively rare dental developmental anomaly characterized by the presence of an accessory cusplike structure projecting from the cingulum area or ce- mentoenamel junction. This occurs in either maxillary or mandibular anterior teeth in both the primary and permanent dentition. This article reports five cases of talon cusp, two of them bilateral, affecting perma- nent maxillary central and lateral incisors and canines that caused clinical problems related to caries or occlusal interferences. (Quintessence Int 2003;34:xxx–xxx) Key words: dens evaginatus, dental anomalies, occlusal interference, talon cusp ens evaginatus is a developmental anomaly char- volved (67%), followed by the central incisors (24%) Dacterized by the presence of an extra cusp, occur- and canines (9%).7,8 ring more frequently in mandibular premolars.1 In ca- Family histories of cases reported previously re- nines and incisors, Dens evaginatus originates usually vealed that sometimes talon cusp affected patients who in the palatal cingulus as a tubercle projecting from had consanguineous parents.6,9 Moreover, there are sev- the palatal surface; however, the anomaly also has af- eral dates [Au: What is meant by “dates?” Reports?] fected the labial surface of the tooth.2,3 Mitchell4 first in the literature that support the hereditary character of described this dental anomaly as a “process of horn- talon cusp: the anomaly has been described affecting like shape, curving from the base downward to the two siblings,10,11 two sets of female twins,12 and two cutting edge” on the lingual surface of an maxillary family members,9 and the prevalence of talon cusp is central incisor of a female patient. -

Gemination with Talon's Cusp on Mandibular Central Incisor

OLGU SUNUMU / CASE REPORT Gülhane Tıp Derg 2016;58: 105-107 © Gülhane Askeri Tıp Akademisi 2016 doi: 10.5455/gulhane. 162948 Gemination with talon’s cusp on mandibular central incisor: An unusual occurrence Dr Renita Lorina Castelino(*), Anusha Rangare Laxmana(**), Sham Kishor Kannepady(**), Preethi Balan(***), Fazil KA(***) Introduction ÖZET Fetal taşikardi en iyi bilinen non-immun hidrops fetalis nedenidir. Fetal taşikardi A developing tooth can undergo variations and fluctuations tedavi edilmezse hidrops fetalise ve fetal kayıba neden olabilmektedir. Hidrops fetaliste prognoz antiaritmik tedaviye hızlı yanıta, gebelik haftasına, fetusun iyilik during tooth development and can result in various haline ve yüksek kardiyovasküler profil skora (KVPS) bağlıdır. Biz burada SVT’ ye developmental anomalies. It can be either in the primary or sekonder gelişen 28 haftalık hidropslu fetusu olgu olarak sunduk. Biz KVPS’u in the permanent dentition. The terms “double teeth”, “double tartışmak amacıyla bu olgu sunumunu sunduk . Olgumuz da Digoksin ve sotalol [1,2,3] den oluşan kombine maternal antiaritmik tedavinin 1. günde fetal taşikardinin formations”, “joined teeth”, “fused teeth”or “dental twinning” başarılı şekilde sinüs ritmine dönüştüğü izlendi fakat fetusun iyilik hali gittikçe are often used to describe the anomaly of conjoined tooth. The bozulup hidrops fetalis ağırlaştı ve tedavinin 21. günü fetal kayıp gerçekleşti. Fetusun kardiyovasküler profil skoru (KVPS) 7/10 ( cilt ödemi 2 puan, duktus terms like germination, schizodontia, connation, synodontia, venozusta revers atriyal A dalgası 1 puan kayıp) idi. Ve bu yaşamla bağdaşır kabul linking tooth [4] have also been suggested in literature. edilebilir bir skordu. Fakat olgumuzda hayatla bağdaşır (7/10) KVPS olmasına rağmen fetal kayıp oluşmuştur. -

Unusual Case Report of Mandibular Talons Cusp

ACTA SCIENTIFIC DENTAL SCIENCES (ISSN: 2581-4893) Volume 2 Issue 12 December 2018 Case Report Unusual Case Report of Mandibular Talons Cusp Suruchi Kadoo Deshpande1 and Nilesh Deshpande2* 1General Dentist, Sunny Medical Centre, A NMC Company, Sharjah, UAE 2Pediatric Dentist, Sunny Medical Centre, A NMC company, Sharjah, UAE *Corresponding Author: Nilesh Deshpande, Pediatric Dentist, Sunny Medical Centre, A NMC company, Sharjah, UAE. Received: October 08, 2018; Published: November 09, 2018 Abstract Talon cusp is a dental anomaly also known as an Eagle’s talon. It is an additional cusp on an anterior tooth which occurs due to evagination on the surface of a crown before calcification. The exact etiology is unknown. The incidence of talon cusp is very less cases bilateral. Double teeth appearance is a typical radiological diagnostic feature. The anomaly rarely found in mandibular denti- which is even lesser in mandibular anteriors. Maxillary incisors are most commonly involved teeth, usually unilateral but in some tion. This article we are reporting an unusual case of talon cusp of permanent mandibular central incisors. Keywords: Talons Cusp; Anomaly; Evagination Introduction The prevalence of this anomaly in the population varies be- Talon cusp, also known as Eagle’s talon, is a manifestation of tween 1% and 8% [5,6]. It is most frequently found in permanent dens evaginatus in the anterior teeth [1]. The incidence has been 94%. Among the incisors, the laterals (55%) and most affected . found to range from less than 1% to 6% of the population, in which teeth 77%, with the maxillary incisors being the most affected [7] (65%) and may be unilateral or bilateral [8]. -

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; -

Concommitant Occurance of Dens Invaginatus and Talon Cusp: a Case Report

Case Report Concommitant occurance of dens invaginatus and talon cusp: A case report Ocorrência simultânea de dens invaginatus e cúspide talon: relato de caso Abstract Monica Yadav a Meghana S.M b a Purpose: Morphological dental anomalies of the maxillary lateral incisors are relatively Sandip R. Kulkarni common. However, their simultaneous occurrence is a relatively rare event. We report a case of dens invaginatus and talon cusp concurrently affecting maxillary lateral incisors. The etiology, pathophysiology, association with other dental anomalies, as well as various treatment a Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, modalities of these anomalies are discussed. Terna Dental College and Hospital, Nerul, Navi Case description: An 18-year-old male patient reported with a complaint of crowding of Mumbai, India maxillary front teeth. On intraoral examination, permanent dentition with Class I malocclusion b Department of Oral Pathology, Terna Dental with anterior crowding was observed. Tooth 12 showed a radiopaque invagination from College and Hospital, Nerul, Navi Mumbai, a lingual pit but confined to the crown of the tooth. This invagination was approximately India circular with a central core of radiolucency, which was consistent with the diagnosis of a dens invaginatus type I. Tooth 22 showed the talon cusp as a typical inverted cone with enamel and dentine layers and a pulp horn extending only into the base of the cusp. Talon cusp was treated by prophylactic enameloplasty to avoid plaque accumulation, the deep lingual pit was sealed using composite resin and regular clinical and radiographic follow-up was advised. Patient was scheduled for orthodontic treatment to correct crowding of maxillary anterior teeth. -

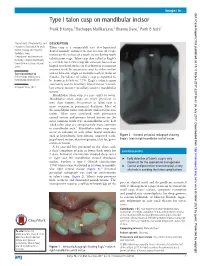

Type I Talon Cusp on Mandibular Incisor Pratik B Kariya,1 Rachappa Mallikarjuna,2 Bhavna Dave,1 Parth B Joshi1

Images in… BMJ Case Reports: first published as 10.1136/bcr-2017-220736 on 26 July 2017. Downloaded from Type I talon cusp on mandibular incisor Pratik B Kariya,1 Rachappa Mallikarjuna,2 Bhavna Dave,1 Parth B Joshi1 1Department of Pedodontics and DESCRIPTION Preventive Dentistry, K M Shah Talon cusp is a comparably rare developmental Dental College and Hospital, dental anomaly assumed to arise because of evagi- Vadodara, India nation on the surface of a tooth crown during tooth 2Pedodontics and Preventive calcification stage. Talon cusp also called as Eagle’s Dentistry, Child Dental Health, Oman Dental College, Muscat, is a well-defined extra cusp like structure located on Oman lingual or palatal surface of deciduous or permanent anterior teeth. Its occurrence may be either unilat- Correspondence to eral or bilateral, single or multiple teeth in males or Dr Rachappa Mallikarjuna, females. Prevalence of talon’s cusp is reported to mmrachappa@ gmail. com be between 0.06% to 7.7%. Eagle’s talon is most commonly seen in maxillary lateral incisor >maxil- Accepted 4 July 2017 lary central incisor> maxillary canine> mandibular incisor.1 Mandibular talon cusp is a rare entity to occur. Mandibular talon cusps are more prevalent in men than women. Occurrence in talon cusp is more common in permanent dentition. Most of the mandibular talon cusp shows unilateral presen- tation. Talon cusp associated with permanent central incisor and primary lateral incisor are the most common tooth type in mandibular arch. Left sided talon cusp are comparatively more common in mandibular arch.1 Mandibular talon cusp may occur in isolation or with other dental anomalies such as hypodontia, hyperdontia, impacted teeth, Figure 2 Intraoral periapical radiograph showing peg-shaped incisor, dens invaginatus, cleft lip, gemi- Eagle’s talon in right mandibular central incisor. -

DAPA 741 Oral Pathology Examination 4 December 6, 2000 1

Name: _____________________ DAPA 741 Oral Pathology Examination 4 December 6, 2000 1. Irregularity of the temporomandibular joint surfaces is a radiographic feature of A. Subluxation B. Osteoarthritis C. Trigeminal neuralgia D. Anterior disk displacement 2. Which of the following is an autoimmune disease? A. Bell’s palsy B. Osteoarthritis C. Rheumatoid arthritis D. Trigeminal neuralgia 3. Which joints are commonly affected in osteoarthritis but usually spared in rheumatoid arthritis? A. Hips B. Joints of the hands C. Knees D. Temporomandibular joint 4. Bell’s palsy may be induced by trauma to which nerve? A. Trigeminal nerve B. Glossopharyngeal nerve C. Facial nerve D. Inferior alveolar nerve 5. A patient presents to your office concerned about a painless click when she open her mouth. Your examination of her temporomandibular joint reveals a click at approximately 15 mm of opening. You instruct her to touch the incisal edges of her maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth together and then open from this position. The click disappears when she opens from this position. You diagnosis is A. Subluxation B. Anterior disk displacement C. Crepitus D. Inflammatory arthralgia 6. An ankylosed joint will cause the mandible to deviate to which side on opening? A. The affected side B. The unaffected side C. There would be no deviation on opening 7. Pain from which of the following commonly awakens the patient at night? A. Masticatory myofascial pain B. Tension headaches C. Trigeminal neuralgia D. Osteoarthritis 8. Which of the following disorders may result in blindness and is thus considered an acute ocular emergency? A. Trigeminal neuralgia B.