Final Dissertation Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amjad Ali Khan & Sharon Isbin

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

WORDS MADE FLESH Code, Culture, Imagination Florian Cramer

WORDS MADE FLESH Code, Culture, Imagination Florian Cramer Me dia De s ign Re s e arch Pie t Z w art Ins titute ins titute for pos tgraduate s tudie s and re s e arch W ille m de Kooning Acade m y H oge s ch ool Rotte rdam 3 ABSTRACT: Executable code existed centuries before the invention of the computer in magic, Kabbalah, musical composition and exper- imental poetry. These practices are often neglected as a historical pretext of contemporary software culture and electronic arts. Above all, they link computations to a vast speculative imagination that en- compasses art, language, technology, philosophy and religion. These speculations in turn inscribe themselves into the technology. Since even the most simple formalism requires symbols with which it can be expressed, and symbols have cultural connotations, any code is loaded with meaning. This booklet writes a small cultural history of imaginative computation, reconstructing both the obsessive persis- tence and contradictory mutations of the phantasm that symbols turn physical, and words are made flesh. Media Design Research Piet Zwart Institute institute for postgraduate studies and research Willem de Kooning Academy Hogeschool Rotterdam http://www.pzwart.wdka.hro.nl The author wishes to thank Piet Zwart Institute Media Design Research for the fellowship on which this book was written. Editor: Matthew Fuller, additional corrections: T. Peal Typeset by Florian Cramer with LaTeX using the amsbook document class and the Bitstream Charter typeface. Front illustration: Permutation table for the pronounciation of God’s name, from Abraham Abulafia’s Or HaSeichel (The Light of the Intellect), 13th century c 2005 Florian Cramer, Piet Zwart Institute Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of any of the following licenses: (1) the GNU General Public License as published by the Free Software Foun- dation; either version 2 of the License, or any later version. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

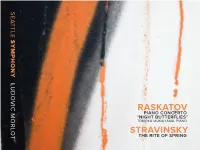

Raskatov Stravinsky

SEATTLE SYMPHONY LUDOVIC MORLOT LUDOVIC RASKATOV PIANO CONCERTO “NIGHT BUTTERFLIES” TOMOKO MUKAIYAMA, PIANO STRAVINSKY THE RITE OF SPRING SEATTLESYMPHONY.ORG � & © 2014 Seattle Symphony Media. All rights reserved. Unauthorized copying, hiring, lending, public performance and broadcasting of this record prohibited without prior written permission from the Seattle Symphony. Benaroya Hall, 200 University Street, Seattle, WA 98101 Photo: Larey McDaniel Larey Photo: SEATTLE SYMPHONY Founded in 1903, the Seattle Symphony is one of America’s leading symphony orchestras and is internationally acclaimed for its innovative programming and extensive recording history. Under the leadership of Music Director Ludovic Morlot since September 2011, the Symphony is heard live from September through July by more than 300,000 people. It performs in one of the finest modern concert halls in the world — the acoustically superb Benaroya Hall — in downtown Seattle. Its extensive education and community-engagement programs reach over 100,000 children and adults each year. The Seattle Symphony has a deep commitment to new music, commissioning many works by living composers each season, including John Luther Adams’ Become Ocean, which won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Music. The orchestra has made more than 140 recordings and has received 12 Grammy nominations, two Emmy Awards and numerous other accolades. In 2014 the Symphony launched its in-house recording label, Seattle Symphony Media. For more information, visit seattlesymphony.org. Photo: Ben VanHouten Ben Photo: LUDOVIC MORLOT, CONDUCTOR As the Seattle Symphony’s Music Director, Ludovic Morlot has been received with extraordinary enthusiasm by musicians and audiences alike, who have praised him for his deeply musical interpretations, his innovative programming and his focus on community collaboration. -

Trimpin Above, Below, and in Between Trimpin

TRIMPIN ABOVE, BELOW, AND IN BETWEEN BELOW, ABOVE, SEATTLE SYMPHONY LUDOVIC MORLOT TRIMPIN Above, Below, and In Between, A site-specific composition Part 1 .............................................................................1:36 Part 2 ............................................................................ 2:55 Part 3 – For Jessika ..................................................... 4:20 Part 4 ............................................................................ 2:34 Part 5 ............................................................................ 6:00 Part 6 ............................................................................ 5:00 Jessika Kenney, soprano; Sayaka Kokubo, viola; Penelope Crane, viola: Eric Han, cello; David Sabee, cello; Jordan Anderson, double bass; Joseph Kaufman, double bass; Ko-ichiro Yamamoto, trombone; David Lawrence Ritt, trombone; Stephen Fissel, trombone TOTAL TIME ............................................................... 22:30 SEATTLESYMPHONY.ORG � & © 2016 Seattle Symphony Media. All rights reserved. Unauthorized copying, hiring, lending, public performance and broadcasting of this record prohibited without prior written permission from the Seattle Symphony. Benaroya Hall, 200 University Street, Seattle, WA 98101 MADE IN USA Photo: Larey McDaniel Larey Photo: SEATTLE SYMPHONY Founded in 1903, the Seattle Symphony is one of America’s leading symphony orchestras and is internationally acclaimed for its innovative programming and extensive recording history. Under the leadership -

2020 WWE Finest

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Angel Garza Raw® 2 Akam Raw® 3 Aleister Black Raw® 4 Andrade Raw® 5 Angelo Dawkins Raw® 6 Asuka Raw® 7 Austin Theory Raw® 8 Becky Lynch Raw® 9 Bianca Belair Raw® 10 Bobby Lashley Raw® 11 Murphy Raw® 12 Charlotte Flair Raw® 13 Drew McIntyre Raw® 14 Edge Raw® 15 Erik Raw® 16 Humberto Carrillo Raw® 17 Ivar Raw® 18 Kairi Sane Raw® 19 Kevin Owens Raw® 20 Lana Raw® 21 Liv Morgan Raw® 22 Montez Ford Raw® 23 Nia Jax Raw® 24 R-Truth Raw® 25 Randy Orton Raw® 26 Rezar Raw® 27 Ricochet Raw® 28 Riddick Moss Raw® 29 Ruby Riott Raw® 30 Samoa Joe Raw® 31 Seth Rollins Raw® 32 Shayna Baszler Raw® 33 Zelina Vega Raw® 34 AJ Styles SmackDown® 35 Alexa Bliss SmackDown® 36 Bayley SmackDown® 37 Big E SmackDown® 38 Braun Strowman SmackDown® 39 "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt SmackDown® 40 Carmella SmackDown® 41 Cesaro SmackDown® 42 Daniel Bryan SmackDown® 43 Dolph Ziggler SmackDown® 44 Elias SmackDown® 45 Jeff Hardy SmackDown® 46 Jey Uso SmackDown® 47 Jimmy Uso SmackDown® 48 John Morrison SmackDown® 49 King Corbin SmackDown® 50 Kofi Kingston SmackDown® 51 Lacey Evans SmackDown® 52 Mandy Rose SmackDown® 53 Matt Riddle SmackDown® 54 Mojo Rawley SmackDown® 55 Mustafa Ali Raw® 56 Naomi SmackDown® 57 Nikki Cross SmackDown® 58 Otis SmackDown® 59 Robert Roode Raw® 60 Roman Reigns SmackDown® 61 Sami Zayn SmackDown® 62 Sasha Banks SmackDown® 63 Sheamus SmackDown® 64 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown® 65 Shorty G SmackDown® 66 Sonya Deville SmackDown® 67 Tamina SmackDown® 68 The Miz SmackDown® 69 Tucker SmackDown® 70 Xavier Woods SmackDown® 71 Adam Cole NXT® 72 Bobby -

2021 Topps WWE NXT Checklist.Xls

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Roderick Strong™ def. Bronson Reed™ NXT 2 Keith Lee™ Retains the NXT® North American Championship NXT TakeOver: Portland 3 The BroserWeights™ Win the NXT® Tag Team Championship NXT TakeOver: Portland 4 NXT® Champion Adam Cole™ def. Tommaso Ciampa™ NXT TakeOver: Portland 5 Johnny Gargano™ Attacks Tommaso Ciampa™ NXT 6 The BroserWeights™ Retain the NXT® Tag Team Championship NXT 7 Tommaso Ciampa™ and Johnny Gargano™ Brawl in the WWE® PC NXT 8 Keith Lee™ def. Dominik Dijakovic™ and Damian Priest™ NXT 9 Johnny Gargano™ def. Tommaso Ciampa™ NXT 10 Timothy Thatcher™ Fills in for The BroserWeights™ NXT 11 Karrion Kross™ Attacks Tommaso Ciampa™ NXT 12 Akira Tozawa™ def. Isaiah "Swerve" Scott™ NXT 13 El Hijo del Fantasma™ Debuts NXT 14 Jake Atlas™ def. Drake Maverick™ NXT 15 Kushida™ def. Tony Nese™ NXT 16 Isaiah "Swerve" Scott™ def. El Hijo del Fantasma™ NXT 17 Imperium™ Attacks Matt Riddle™ & Timothy Thatcher™ NXT 18 Drake Maverick™ def. Tony Nese™ NXT 19 NXT® North American Champion Keith Lee™ def. Damian Priest™ NXT 20 Johnny Gargano™ def. Dominik Dijakovic™ NXT 21 Karrion Kross™ def. Leon Ruff™ NXT 22 Adam Cole™ Retains the NXT® Championship NXT 23 Akira Tozawa™ Picks up a Tournament Victory NXT 24 Kushida™ def. Jake Atlas™ NXT 25 Jake Atlas™ def. Tony Nese™ NXT 26 Imperium™ Wins the NXT® Tag Team Championship NXT 27 Damian Priest™ Attacks Finn Bálor™ NXT 28 Riddle™ def. Timothy Thatcher™ NXT 29 El Hijo del Fantasma™ Wins Group B NXT 30 Roderick Strong™ def. Dexter Lumis™ NXT 31 Drake Maverick™ Wins Group A NXT 32 Tommaso Ciampa™ def. -

Wilco-Songs Minimalistisch

Folkdays … Wilco-Songs minimalistisch Musik | Jeff Tweedy: Together At Last Jeff Tweedy, das ist einerseits ein Singer-Songwriter, andererseits ist er der Macher von Wilco in Zusammenarbeit mit John Stirratt, Glenn Kotche, Mikael Jorgensen, Nels Cline und Pat Sansone. Er war auch einmal mit dem Band-Projekt Golden Smog zu hören und es gibt neue Bands von ihm genannt Loose Fur und Tweedy. Das zuerst kurz als Fakten. Von TINA KAROLINA STAUNER Das neue Album von Jeff Tweedy ›Together At Last‹ ist wie ein Überbleibsel aus einer Zeit, in der die Freude Americana, Alternative Country und Neofolk zu hören manchmal fast ungetrübt war. Kein Mainstream laberte irgendeinen Klimbim dazwischen und neben Befindlichkeits- und Beziehungstexten war Sozial- und Gesellschaftskritik in Lyrics ein Zeichen für Anspruch und Niveau. Die Chicagoer Independent-Band Wilco hatte sich mit den ersten Alben in den 1990er Jahren mit Leib und Seele in den Spirit einer ganzen Independent-Generation gespielt. Entstanden aus Uncle Tupelo war Wilco immer wichtig im Diskurs. Bezogen auf traditionelles Wissen über Country und Folk hatte die Band einen ureigenen Sound und integrierte manchmal auch neue und elektronische Klänge in den Kontext. Mittlerweile scheint Jeff Tweedy teils zynisch bis zum geht-nicht-mehr und nach ›Star Wars‹ und ›Schmilco‹ mit Cover-Artwork wie ein Cartoon kam ein ›Together At Last‹. Vergangenheit ist das Woody Guthrie Project, das er mit Nora Guthrie und Billy Bragg vor Jahren veröffentlichte. Vergangenheit sind die frühen Independent-Jahre, wenn es überhaupt noch Leute gibt, die sich daran erinnern. Vergangenheit ist die Band-Dokumentation ›Man in the Sand‹. Vergangenheit sind Songs wie ›In A Future Age‹. -

Noise in Music Or Music in Noise? a Short Discussion on the Incorporation of “Other” Sounds in Music Making

University of Alberta Noise in Music or Music in Noise? A Short Discussion on the Incorporation of “Other” Sounds in Music Making Essay Submitted as part of the Music History exam of the Qualifying Exams, for the degree of Doctor in Music Composition Faculty of Arts Department of Music by Nicolás Alejandro Mariano Arnáez Edmonton, Alberta January 2017 “We affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath— a roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.” (Marinetti 1909) Introduction When a physical source produces periodic or aperiodic vibrations in the air within a certain frequency, and there are human ears near by, they receive a meaning assigned by our brain. When we have the necessity of verbalize the sonic image produced by those vibrations, we need to choose a word available in our language that best describes what we felt sonically. Words associated with this practice of describing what we perceive are commonly “sound”, “noise”, “music”, “tone”, and such. The question is, what does make us to choose within one word or another? Many inquiries will arise if we analyze our selection. For example, if we say “that is music” we may be implying that music is not tone, or noise, or even sound! Personally speaking, I find a deep and intimate sensation of peace when hearing the sound of water moving in a natural environment, it generates that specific feeling on my human brain and body. -

Oceanic Migrations

San Francisco Contemporary Music Players on STAGE series Oceanic Migrations MICHAEL GORDON ROOMFUL OF TEETH SPLINTER REEDS September 14, 2019 Cowell Theater Fort Mason Cultural Center San Francisco, CA SFCMP SAN FRANCISCO CONTEMPORARY MUSIC PLAYERS San Francisco Contemporary Music Brown, Olly Wilson, Michael Gordon, Players is the West Coast’s most Du Yun, Myra Melford, and Julia Wolfe. long-standing and largest new music The Contemporary Players have ensemble, comprised of twenty-two been presented by leading cultural highly skilled musicians. For 49 years, festivals and concert series including the San Francisco Contemporary Music San Francisco Performances, Los Players have created innovative and Angeles Monday Evening Concerts, Cal artistically excellent music and are one Performances, the Stern Grove Festival, Tod Brody, flute Kate Campbell, piano of the most active ensembles in the the Festival of New American Music at Kyle Bruckmann, oboe David Tanenbaum, guitar United States dedicated to contemporary CSU Sacramento, the Ojai Festival, and Sarah Rathke, oboe Hrabba Atladottir, violin music. Holding an important role in the France’s prestigious MANCA Festival. regional and national cultural landscape, The Contemporary Music Players Jeff Anderle, clarinet Susan Freier, violin the Contemporary Music Players are a nourish the creation and dissemination Peter Josheff, clarinet Roy Malan, violin 2018 awardee of the esteemed Fromm of new works through world-class Foundation Ensemble Prize, and a performances, commissions, and Adam Luftman, -

Chuck Klosterman on Pop

Chuck Klosterman on Pop A Collection of Previously Published Essays Scribner New York London Toronto Sydney SCRIBNER A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 www.SimonandSchuster.com Essays in this work were previously published in Fargo Rock City copyright © 2001 by Chuck Klosterman, Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs copyright © 2003, 2004 by Chuck Klosterman, Chuck Klosterman IV copyright © 2006, 2007 by Chuck Klosterman, and Eating the Dinosaur copyright © 2009 by Chuck Klosterman. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020. First Scribner ebook edition September 2010 SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work. For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1- 866-506-1949 or [email protected]. The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com. Manufactured in the United States of America ISBN 978-1-4516-2477-9 Portions of this work originally appeared in The New York Times Magazine, SPIN magazine, and Esquire. Contents From Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs and Chuck Klosterman IV The -

Claes-Göran Holmberg

fLaMMan claes-Göran holmberg Precursors swedish avant-garde groups were very late in founding their own magazines. in france and Germany, little magazines had been pub- lished continuously from the romantic era onwards. a magazine was an ideal platform for the consolidation of a new movement in its formative phase. it was a collective thrust at the heart of the enemy: the older generation, the academies, the traditionalists. By showing a united front (through programmatic declarations, manifestos, es- says etc.) you assured the public that you were to be reckoned with. almost every new artist group or current has tried to create a mag- azine to define and promote itself. the first swedish little magazine to embrace the symbolist and decadent movements of fin-de-siècle europe was Med pensel och penna (With paintbrush and pen, 1904-1905), published in Uppsala by the society of “Les quatres diables”, a group of young poets and students engaged in aestheticism and Baudelaire adulation. Mem- bers were the poet and student in slavic languages sigurd agrell (1881-1937), the student and later professor of art history harald Brising (1881-1918), the student of philosophy and later professor of psychology John Landquist (1881-1974), and the author sven Lidman (1882-1960); the poet sigfrid siwertz (1882-1970) also joined the group later. the magazine did not leave any great impact on swedish literature but it helped to spread the Jugend style of illu- stration, the contemporary love-hate relationship with the city and the celebration of the intoxicating powers of beauty and deca- dence.