Vaginal Bleeding in Late Pregnancy Objectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heterotopic Cervical Pregnancy

Elmer ress Case Report J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2015;4(4):307-311 Heterotopic Cervical Pregnancy Mathangi Thangavelua, b, Ravinder Kalkata Abstract tenderness or cervical excitation. Initial hormonal investiga- tions showed BHCG levels were raised to 17,276 IU and ini- We report a rare case of heterotopic cervical pregnancy, which posed tial ultrasound was suggestive of minimal retained products diagnostic challenge. With increasing IVF treatment and raising ce- of conception (Fig. 1). However, a repeat BHCG showed an sarean section rate, there is increasing incidence for non-tubal hetero- increasing trend reaching up to 29,971 IU in 96 h. A repeat topic pregnancy. We have discussed the clinical course of our case, transvaginal scan showed the endometrial cavity had mixed diagnosis and management of cervical pregnancy and some good echoes and multiple cystic spaces, largest measuring 6 × 7 × medical practices to avoid missing atypical presentations of ectopic 8 mm with color flow suggesting a possible molar pregnancy pregnancy. (Fig. 2). Bilateral ovarian cysts were present in both adnexa. Laparoscopy and dilatation and curettage were arranged Keywords: Cervical pregnancy; Heterotopic; Ectopic in view of high BHCG levels and no clear evidence of intrau- terine pregnancy. Laparoscopy was negative for tubal ectopic pregnancy and dilatation and curettage was performed. Post- operatively BHCG levels were monitored to ensure its levels were declining. The levels initially dropped to 2,611 IU from Introduction 29,971 IU in a week after D&C. However, the subsequent BHCG levels doubled to 4,207 IU 2 weeks after D&C. With We report an extremely rare case of spontaneous heterotopic the knowledge of earlier scan findings, raising BHCG levels cervical pregnancy who needed multiple investigations before raised the concern of persistent trophoblastic disease. -

Successful Treatment of Cervical Ectopic Pregnancy with Multi Dose

Case Report iMedPub Journals Gynaecology & Obstetrics Case report 2020 www.imedpub.com ISSN 2471-8165 Vol.6 No.2:14 DOI: 10.36648/2471-8165.6.2.94 Successful Treatment of Cervical Ectopic Iqbal S1*, Iqbal J2, Nowshad N1 and Pregnancy with Multi Dose Methotrexate Mohammad K1 Therapy 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Latifa Hospital, Dubai Health Authority Jaddaf, Dubai, UAE 2 Department of Medical Education, Dubai Abstract Medical University, Dubai, UAE Cervical ectopic pregnancies account for less than 1% of all pregnancies. Earlier, it was associated with significant hemorrhage and was treated presumptively with hysterectomy. With the advent of enhanced ultrasound techniques, early *Corresponding author: Iqbal S detection of these pregnancies has led to the development of more effective conservative management. We present a case of a cervical ectopic pregnancy successfully treated with multi-dose Methotrexate therapy. [email protected] A 37-year-old lady, G3P0+2, pregnant for 9 weeks and 4 days, presented with bleeding per vagina, mild lower abdomen and back pain. Serum Beta-hCG done Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 5 days ago was 950 mIU/mL. She was diagnosed as ectopic cervical pregnancy Latifa Hospital, Dubai Health Authority by clinical examination which was confirmed by transvaginal ultrasonography Jaddaf, Dubai, UAE. and subsequently managed by Methotrexate (MTX) Hybrid double dose protocol. Due to rising Beta-hCG and continuous bleeding, it was modified to Multi dose Tel: 971569400124 Methotrexate Therapy. Thereafter, the patient was asymptomatic with falling beta-hCG and she was put on a weekly follow up in the clinic. Keywords: Ectopic pregnancy; Cervical pregnancy; Methrotrexate; Gynaecology Citation: Iqbal S, Iqbal J, Nowshad N, Mohammad K (2020) Successful Treatment of Cervical Ectopic Pregnancy with Multi Received: March 31, 2020; Accepted: May 02, 2020; Published: May 06, 2020 Dose Methotrexate Therapy. -

AUC Instructions / ૂચના

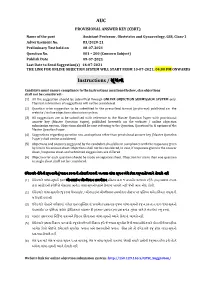

AUC PROVISIONAL ANSWER KEY (CBRT) Name of the post Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, GSS, Class-1 Advertisement No. 83/2020-21 Preliminary Test held on 08-07-2021 Question No. 001 – 200 (Concern Subject) Publish Date 09-07-2021 Last Date to Send Suggestion(s) 16-07-2021 THE LINK FOR ONLINE OBJECTION SYSTEM WILL START FROM 10-07-2021; 04:00 PM ONWARDS Instructions / ૂચના Candidate must ensure compliance to the instructions mentioned below, else objections shall not be considered: - (1) All the suggestion should be submitted through ONLINE OBJECTION SUBMISSION SYSTEM only. Physical submission of suggestions will not be considered. (2) Question wise suggestion to be submitted in the prescribed format (proforma) published on the website / online objection submission system. (3) All suggestions are to be submitted with reference to the Master Question Paper with provisional answer key (Master Question Paper), published herewith on the website / online objection submission system. Objections should be sent referring to the Question, Question No. & options of the Master Question Paper. (4) Suggestions regarding question nos. and options other than provisional answer key (Master Question Paper) shall not be considered. (5) Objections and answers suggested by the candidate should be in compliance with the responses given by him in his answer sheet. Objections shall not be considered, in case, if responses given in the answer sheet /response sheet and submitted suggestions are differed. (6) Objection for each question should be made on separate sheet. Objection for more than one question in single sheet shall not be considered. ઉમેદવાર નીચેની ૂચનાઓું પાલન કરવાની તકદાર રાખવી, અયથા વાંધા- ૂચન ગે કરલ રૂઆતો યાને લેવાશે નહ (1) ઉમેદવાર વાંધાં- ૂચનો ફત ઓનલાઈન ઓશન સબમીશન સીટમ ારા જ સબમીટ કરવાના રહશે. -

A Case of Cervical Ectopic Pregnancy JAHANARA BEGUM1, SHAMSUNNAHAR BEGUM (HENA)2, ROWSHAN ARA3, SHAMIM FATEMA NARGIS4

Bangladesh J Obstet Gynaecol, 2012; Vol. 27(1) : 31-35 A Case of Cervical Ectopic Pregnancy JAHANARA BEGUM1, SHAMSUNNAHAR BEGUM (HENA)2, ROWSHAN ARA3, SHAMIM FATEMA NARGIS4 Abstract: Cervical ectopic pregnancy is the implantation of a pregnancy in the endocervix1. Such pregnancy typically aborts within the first trimester, if it is implanted closer to the uterine cavity called cervico isthmic pregnancy it may continue longer2. Cervical pregnancy accounts for less than 1% of all ectopic pregnancies, with an estimated incidence of one in 2500 to one in 180003-5. Though the pregnancy in this area is uncommon but possibly life threatening condition due to risk of severe hemorrhage and may need hysterectomy. Early detection and conservative approach of treatment limit the morbidity and preserve fertility. A 26 years lady diagnosed as a case of cervical ectopic pregnancy and managed conservatively successfully with adjunctive techniques like cervical artery ligation and cervical temponade to control haemorrhage. The case is reported here for its relative rarity. Key Words: Cervical Ectopic, Intractable bleeding, Cervical artery ligation, cervical temponade. Introduction: and duration. She was married for 5 years, having In ectopic pregnancy the fertilized ovum becomes no issue and no history of MR or D and C. She had implanted in a site other than normal uterine cavity. It is no relevant family history. On general examination the consequence of an abnormal implantation of the she was mildly anaemic, normotensive. On per blastocyst. Worldwide incidence of ectopic pregnancy abdominal examination nothing abnormal was is 3-4% but the incidence is rising. In some studies the detected. -

Sexual and Reproductive Health

Sexual and Reproductive Health Guide for the Care of the Most Relevant Obstetric Emergencies Guide for the Care of the Most Relevant Obstetric Emergencies Fescina R*, De Mucio B*, Ortiz El**, Jarquin D**. *Latin American Center for Perinatology Women and Reproductive Health **Latin American Federation of Societies of Obstetrics and Gynecology Scientific Publication CLAP/WR N° 1594-02 Latin American Center for Perinatology Women and Reproductive Health CLAP/ WR Sexual and Reproductive Health Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Fescina R, De Mucio B, Ortiz E, Jarquin D. Guide for the care of the most relevant obstetric emergencies. Montevideo: CLAP/WR; 2013. (CLAP/WR. Scientific Publication; 1594-02) ISBN: 1. Maternal Mortality - Prevention 2. Pregnancy Complications 3. Placenta Previa 4. Pre-Eclampsia 5. Pregnancy Complications, Infectious 6. Eclampsia 7. Postnatal care 8. Postpartum Hemorrhage 9. Pregnancy, High-Risk 10.Pregnancy, Ectopic I. CLAP/WR II.Title The Pan American Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications, in part or in full. Applications and inquiries should be addressed to Editorial Services, Area of Knowledge Management and Communications (KMC), Pan American Health Organization, Washington, D.C., U.S.A. The Latin American Center for Perinatology, Women and Reproductive Health (CLAP/WR), Area of Family and Community Health, Pan American Health Organization, will be glad to provide the latest information on any changes made to the text, plans for new editions, and reprints and translations already available. © Pan American Health Organization, 2013 All rights reserved. Publications of the Pan American Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. -

Board-Review-Series-Obstetrics-Gynecology-Pearls.Pdf

ObstetricsandGynecology BOARDREVIEW Third Edition Stephen G. Somkuti, MD, PhD Associate Professor Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences Temple University School of Medicine School Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Director, The Toll Center for Reproductive Sciences Division of Reproductive Endocrinology Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Abington Memorial Hospital Abington Reproductive Medicine Abington, Pennsylvania New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2008 by the McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-164298-6 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-149703-X. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. -

Ectopic Pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy Reviewed By Peter Chen MD, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Pennsylvania Medical «more » Definition An ectopic pregnancy is an abnormal pregnancy that occurs outside the womb (uterus). The baby cannot survive. Alternative Names Tubal pregnancy; Cervical pregnancy; Abdominal pregnancy Causes, incidence, and risk factors An ectopic pregnancy occurs when the baby starts to develop outside the womb (uterus). The most common site for an ectopic pregnancy is within one of the tubes through which the egg passes from the ovary to the uterus (fallopian tube). However, in rare cases, ectopic pregnancies can occur in the ovary, stomach area, or cervix. An ectopic pregnancy is usually caused by a condition that blocks or slows the movement of a fertilized egg through the fallopian tube to the uterus. This may be caused by a physical blockage in the tube. Most cases are a result of scarring caused by: y Past ectopic pregnancy y Past infection in the fallopian tubes y Surgery of the fallopian tubes Up to 50% of women who have ectopic pregnancies have had swelling (inflammation) of the fallopian tubes (salpingitis) or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Some ectopic pregnancies can be due to: y Birth defects of the fallopian tubes y Complications of a ruptured appendix y Endometriosis y Scarring caused by previous pelvic surgery In a few cases, the cause is unknown. Sometimes, a woman will become pregnant after having her tubes tied (tubal sterilization). Ectopic pregnancies are more likely to occur 2 or more years after the procedure, rather than right after it. In the first year after sterilization, only about 6% of pregnancies will be ectopic, but most pregnancies that occur 2 - 3 years after tubal sterilization will be ectopic. -

Complications of Pregnancy, Childbirth and the Puerperium Diagnosis Codes

Complications of Pregnancy, Childbirth and the Puerperium Diagnosis Codes 10058006 Miscarriage with amniotic fluid embolism (disorder) SNOMEDCT 10217006 Third degree perineal laceration (disorder) SNOMEDCT 102872000 Pregnancy on oral contraceptive (finding) SNOMEDCT 102873005 Pregnancy on intrauterine device (finding) SNOMEDCT 102875003 Surrogate pregnancy (finding) SNOMEDCT 102876002 Multigravida (finding) SNOMEDCT 106004004 Hemorrhagic complication of pregnancy (disorder) SNOMEDCT 106007006 Maternal AND/OR fetal condition affecting labor AND/OR delivery SNOMEDCT (disorder) 106008001 Delivery AND/OR maternal condition affecting management (disorder) SNOMEDCT 106009009 Fetal condition affecting obstetrical care of mother (disorder) SNOMEDCT 106010004 Pelvic dystocia AND/OR uterine disorder (disorder) SNOMEDCT 10853001 Obstetrical complication of general anesthesia (disorder) SNOMEDCT 111451002 Obstetrical injury to pelvic organ (disorder) SNOMEDCT 111452009 Postpartum afibrinogenemia with hemorrhage (disorder) SNOMEDCT 111453004 Retained placenta, without hemorrhage (disorder) SNOMEDCT 111454005 Retained portions of placenta AND/OR membranes without SNOMEDCT hemorrhage (disorder) 111458008 Postpartum venous thrombosis (disorder) SNOMEDCT 11209007 Cord entanglement without compression (disorder) SNOMEDCT 1125006 Sepsis during labor (disorder) SNOMEDCT 11454006 Failed attempted abortion with amniotic fluid embolism (disorder) SNOMEDCT 11687002 Gestational diabetes mellitus (disorder) SNOMEDCT 11942004 Perineal laceration involving pelvic -

Successful Treatment of a Cervical Ectopic Pregnancy with Single-Dose Methotrexate Therapy

Successful treatment of a cervical ectopic pregnancy with single-dose methotrexate therapy Abstract Ectopic pregnancies implanted in the cervix account for less than one percent of all extra-uterine pregnancies. Due to the rare incidence of cervical ectopic pregnancies, there are no established guidelines for medical versus surgical management. We report a case of a cervical ectopic pregnancy with a fetal heartbeat successfully treated with single-dose methotrexate therapy. Keywords cervical ectopic pregnancy, methotrexate, pregnancy Introduction An ectopic pregnancy is a pregnancy that is implanted outside of the uterus, most commonly within the fallopian tube, but can occur in other rare sites such as the cervical canal. Cervical ectopic pregnancies occur in 1 in 9000 pregnancies.1,2 An ectopic pregnancy implanted in the cervical canal is considered a non-viable gestation with high risk for maternal morbidity and mortality. Prior reports describe multi-dose methotrexate therapy for an embryo with no fetal pole, and direct potassium chloride (KCL) injection into the gestational sac if a heartbeat is present.3 We report a case of a cervical ectopic pregnancy with a fetal heartbeat successfully treated with single-dose methotrexate therapy. Case Description A 22-year-old gravida 2 para 0 at 6 weeks and 5 days gestational age by the last menstrual period presented to the emergency room with heavy vaginal bleeding. A previous dating and viability transvaginal ultrasound at her OB/GYN’s office was suspicious for a cervical ectopic pregnancy. She reported no previous medical conditions. The patient’s obstetric history was significant for a previous dilation and curettage at 7 weeks and 3 days gestation due to a spontaneous abortion. -

PP-091 Interest of Ultrasound Measurement of Cervical Length In

11th Congress of the Mediterranean Association for Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology and she wanted to terminate her pregnancy. After receiving vaginal examination showed a greater than 1 finger dilatation the consent of her husband, preoperative preparation was in 69% of cases with a deletion greater than 50% in 40% of made. Curettage was performed in the operating room. No cases. Cervical length is in 41% of patients lower or equal to complication occurred. The patient was discharged after 25 mm and in 59% of patients it is less than 25mm. The aver- postoperative 6rd hour. age length of the neck is 26.85mm. For an equal length of neck 25 mm negative predictive value is equal to 86.27 with Results: Historically, it was difficult to diagnose CPs and good specificity to 68.75. For cervical length 20mm we have they were identified at later gestational ages compared to the a weak VPN. For cervical length 30mm we have a low speci- tubal ectopic pregnancies. Since the cervical tissue had a rel- ficity. Of the 100 women admitted for MAP 28 and 72 gave atively large gestational sac and a highly vascular nature, birth prematurely to an end. treatment of CP was often associated with massive hemor- rhage from the implantation site, frequently requiring hys- Conclusion: The measurement of the cervix by trans-vaginal terectomy. In a study performed by Matteo et al. in 2006, the ultrasound is a part of everyday obstetric practice. Objectivity authors also used hysteroscopy to successfully resect a CP and low inter-operator variability allowed such additional (after two cycles of methotrexate treatment in this patient) examination to become an extension of the clinical examina- and they found that the hemostasis could be achieved via tion. -

Placenta Accreta: the Silent Invader

International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology Dwivedi S et al. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2016 May;5(5):1501-1505 www.ijrcog.org pISSN 2320-1770 | eISSN 2320-1789 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20161312 Research Article Placenta accreta: the silent invader Seema Dwivedi*, Gopaal Narayan Dwivedi, Archana Kumar, Neena Gupta, Vinita Malhotra, Neha Singh Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, GSVMTushar Medical Kanti College, Das Kanpur University, Kanpur, UP, India Received: 26 February 2016 Revised: 02 April 2016 Accepted: 07 April 2016 *Correspondence: Dr. Seema Dwivedi, E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © the author(s), publisher and licensee Medip Academy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Background: To review incidence causes, clinical presentations, management, maternal mortality and morbidity associated with placenta accreta. Methods: A prospective study was carried out at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, GSVM Medical College, Kanpur during the period of January 2010 to December 2014. During this period all the patients who were diagnosed with placenta accreta were included in the study. Results: Majority of patients presenting with placenta accreta belonged to age group 30-35 years (46%) were multigravida (95%) came from both rural and urban background. Majority of deliveries complicated by placenta accrete were booked cases (78%). Previous LSCS with placenta previa proved to be the major cause (86%). Out of whole spectrum including placenta accreta, increta, percreta, placenta accreta was the commonest of all and placenta percreta required maximum number of blood transfusions (5-6 units of blood on an average). -

Ectopic Pregnancy

ECTOPIC PREGNANCY RmG: FEb, 2016. @KIjOhs KIZZA jOhN KIjOHS Main • Introduction • Types • Etiology / Risk factors • Outcome • Manifestations / S & Sx • Examination findings • Investigations / Role of ultrasonography other us • Management • Ddx Introduction >Main • Implantation of fertilized ovum outside the uterine cavity • Owing to delayed transport • Contributes to maternal mortality and morbidity • Frequency, ≈2% in all pregnancies, 9% after IVF, incidence increased due PID/ infertility • 45% missed on initial ED visits • Main cause of maternal deaths during first trimester • Has S & Sx of normal pregnancy early Types >Main Extra_uterine Tubal – Commonest ≈ 97% Ampullaru ≈65-70% Isthmic ≈20-25% Fimbrial ≈1-2% Interstitial ≈1-2% Ovarian Ligamentary Abdominal Hysterotomy scar pregnancy >Main Uterine tend to rapture much later Cervical; Cornual – in rudimentary horn of a bicornuate uterus which may or may not connect with the uterus Intramural Heterotopic pregnancy – rare 1:30,000 low risk pregnancies 1:7000 pregnancies involving assisted reproductive technology >Main Ovarian Pregnancy • Rare • Spiegelberg’s criteria for diagnosis (1) Tube on affected side must be intact. (2) Gestation sac must be in the position of the ovary. (3) Gestation sac is connected to the uterus by the ovarian ligament. (4) Ovarian tissue must be found on the wall of the gestation sac at histology. • Embedding may occur intra follicular or extra follicular. • In either type rupture is inevitable. • Salpingo-oophorectomy is the definitive surgery.