The Isan Saga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Genomes Document Multiple Waves of Migration in Southeast

Ancient genomes document multiple waves of migration in Southeast Asian prehistory Mark Lipson, Olivia Cheronet, Swapan Mallick, Nadin Rohland, Marc Oxenham, Michael Pietrusewsky, Thomas Oliver Pryce, Anna Willis, Hirofumi Matsumura, Hallie Buckley, et al. To cite this version: Mark Lipson, Olivia Cheronet, Swapan Mallick, Nadin Rohland, Marc Oxenham, et al.. Ancient genomes document multiple waves of migration in Southeast Asian prehistory. Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2018, 361 (6397), pp.92 - 95. 10.1126/science.aat3188. cea-01870144 HAL Id: cea-01870144 https://hal-cea.archives-ouvertes.fr/cea-01870144 Submitted on 19 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. RESEARCH HUMAN GENOMICS wide data using in-solution enrichment, yielding sequences from 18 individuals (Table 1 and table S1) (19). Because of poor preservation conditions in tropical environments, we observed both a low Ancient genomes document multiple rate of conversion of screened samples to work- ing data and also limited depth of coverage per waves of migration in Southeast sample, and thus we created multiple libraries per individual (102 in total in our final dataset). Asian prehistory We initially analyzed the data by performing principal component analysis (PCA) using two different sets of present-day populations (19). -

Section II: Periodic Report on the State of Conservation of the Ban Chiang

Thailand National Periodic Report Section II State of Conservation of Specific World Heritage Properties Section II: State of Conservation of Specific World Heritage Properties II.1 Introduction a. State Party Thailand b. Name of World Heritage property Ban Chiang Archaeological Site c. Geographical coordinates to the nearest second North-west corner: Latitude 17º 24’ 18” N South-east corner: Longitude 103º 14’ 42” E d. Date of inscription on the World Heritage List December 1992 e. Organization or entity responsible for the preparation of the report Organization (s) / entity (ies): Ban Chiang National Museum, Fine Arts Department - Person (s) responsible: Head of Ban Chiang National Museum, Address: Ban Chiang National Museum, City and Post Code: Nhonghan District, Udonthanee Province 41320 Telephone: 66-42-208340 Fax: 66-42-208340 Email: - f. Date of Report February 2003 g. Signature on behalf of State Party ……………………………………… ( ) Director General, the Fine Arts Department 1 II.2 Statement of significance The Ban Chiang Archaeological Site was granted World Heritage status by the World Heritage Committee following the criteria (iii), which is “to bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared ”. The site is an evidence of prehistoric settlement and culture while the artifacts found show a prosperous ancient civilization with advanced technology which had evolved for 5,000 years, such as rice farming, production of bronze and metal tools, and the production of pottery which had its own distinctive characteristics. The prosperity of the Ban Chiang culture also spread to more than a hundred archaeological sites in the Northeast of Thailand. -

A Practical Approach Toward Sustainable Development

A PRACTICAL APPROACH TOWARD SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT THAILAND’S SUFFICIENCY ECONOMY PHILOSOPHY A PRACTICAL APPROACH TOWARD SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT THAILAND’S SUFFICIENCY ECONOMY PHILOSOPHY TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Foreword 32 Goal 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure 6 SEP at a Glance TRANSFORMING INDUSTRY THROUGH CREATIVITY 8 An Introduction to the Sufficiency 34 Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities Economy Philosophy A PEOPLE-CENTERED APPROACH TO EQUALITY 16 Goal 1: No Poverty 36 Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and THE SEP STRATEGY FOR ERADICATING POVERTY Communities SMARTER, MORE INCLUSIVE URBAN DEVELOPMENT 18 Goal 2: Zero Hunger SEP PROMOTES FOOD SECURITY FROM THE ROOTS UP 38 Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production 20 Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being SEP ADVOCATES ETHICAL, EFFICIENT USE OF RESOURCES AN INCLUSIVE, HOLISTIC APPROACH TO HEALTHCARE 40 Goal 13: Climate Action 22 Goal 4: Quality Education INSPIRING SINCERE ACTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE INSTILLING A SUSTAINABILITY MINDSET 42 Goal 14: Life Below Water 24 Goal 5: Gender Equality BALANCED MANAGEMENT OF MARINE RESOURCES AN EGALITARIAN APPROACH TO EMPOWERMENT 44 Goal 15: Life on Land 26 Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation SEP ENCOURAGES LIVING IN HARMONY WITH NATURE A SOLUTION TO THE CHALLENGE OF WATER SECURITY 46 Goal 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions 28 Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy A SOCIETY BASED ON VIRTUE AND INTEGRITY EMBRACING ALTERNATIVE ENERGY SOLUTIONS 48 Goal 17: Partnerships for the Goals 30 Goal 8: Decent Work and FORGING SEP FOR SDG PARTNERSHIPS Economic Growth SEP BUILDS A BETTER WORKFORCE 50 Directory 2 3 FOREWORD In September 2015, the Member States of the United Nations resilience against external shocks; and collective prosperity adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, comprising through strengthening communities from within. -

Lifestyle and Health Care of the Western Husbands in Kumphawapi District, Udon Thani Province,Thailand

7th International Conference on Humanities and Social Sciences “ASEAN 2015: Challenges and Opportunities” (Proceedings) Lifestyle and Health Care of the Western Husbands in Kumphawapi District, Udon Thani Province,Thailand 1. Mrs.Rujee Charupash, M.A. (Sociology), B.sc. (Nursing), Sirindhron College of Public Health, Khon Kaen. (Lecturer), [email protected] Abstract This qualitative research aims to study lifestyle and health care of Western husbands who married Thai wives and live in Kumphawapi District, Udon Thani Province. Five samples were purposively selected and primary qualitative data were collected through non-participant observations and in-depth interviews. The data was reviewed by Methodological Triangulation; then, the Typological Analysis was presented descriptively. Results: 1) Lifestyle of the Western husbands: In daily life, they had low cost of living in the villages and lived on pensions or savings that are only sufficient. Accommodation and environmental conditions, such as mothers’ modern western facilities for their convenience and overall surroundings are neat and clean. 2) Health care: the Western husbands who have diabetes, hypertension and heart disease were looked after by Thai wives to maintain dietary requirements of the disease. Self- treatment occurred via use of the drugstore or the local private clinic for minor illnesses. If their symptoms were severe or if they needed a checkup, they used the services of a private hospital in Udon Thani Province. They used their pension and savings for medical treatments. If a treatment expense exceeded their budget, they would go back to their own countries. Recommendations: The future study should focus on official Thai wives whose elderly Western husbands have underlying chronic diseases in order to analyze their use of their health care services, welfare payments for medical expenses and how the disbursement system of Thailand likely serves elderly citizens from other countries. -

Changing Paradigms in Southeast Asian Archaeology

CHANGING PARADIGMS IN SOUTHEAST ASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY Joyce C. White Institute for Southeast Asian Archaeology and University of Pennsylvania Museum ABSTRACT (e.g., Tha Kae, Ban Mai Chaimongkol, Non Pa Wai, and In order for Southeast Asian archaeologists to effectively many other sites in central Thailand; but see White and engage with global archaeological discussions of the 21st Hamilton [in press] for progress on Ban Chiang). century, adoption of new paradigms is advocated. The But what I want to focus on here is our paradigmatic prevalent mid-twentieth century paradigm’s reliance on frameworks. Paradigms — that set of assumptions, con- essentialized frameworks and directional macro-views cepts, values, and practices that underlie an intellectual dis- should be replaced with a forward-facing, “emergent” cipline at particular points in time — matter. They matter paradigm and an emphasis on community-scale analyses partly because if we are parroting an out-of-date archaeo- in alignment with current trends in archaeological theory. logical agenda, we will miss out on three important things An example contrasting the early i&i pottery with early crucial for the vitality of the discipline of Southeast Asian copper-base metallurgy in Thailand illustrates how this archaeology in the long term. First is institutional support new perspective could approach prehistoric data. in terms of jobs. Second is resources. In both cases, appli- cants for jobs and grants need to be in tune with scholarly trends. Third, what interests me most in this paper, is our place in global archaeological discussions. Participating in INTRODUCTION global archaeological conversations, being a player in tune with the currents of the time, tends to assist in gaining in- When scholars reach the point in their careers that they are 1 stitutional support and resources. -

Department of Social Development and Welfare Ministry of Social

OCT SEP NOV AUG DEC JUL JAN JUN FEB MAY MAR APR Department of Social Development and Welfare Ministry of Social Development and Human Security ISBN 978-616-331-053-8 Annual Report 2015 y t M i r i u n c is e t S ry n o a f m So Hu ci d al D an evelopment Department of Social Development and Welfare Annual Report 2015 Department of Social Development and Welfare Ministry of Social Development and Human Security Annual Report 2015 2015 Preface The Annual Report for the fiscal year 2015 was prepared with the aim to disseminate information and keep the general public informed about the achievements the Department of Social Development and Welfare, Ministry of Social Development and Human Security had made. The department has an important mission which is to render services relating to social welfare, social work and the promotion and support given to local communities/authorities to encourage them to be involved in the social welfare service providing.The aim was to ensure that the target groups could develop the capacity to lead their life and become self-reliant. In addition to capacity building of the target groups, services or activities by the department were also geared towards reducing social inequality within society. The implementation of activities or rendering of services proceeded under the policy which was stemmed from the key concept of participation by all concerned parties in brainstorming, implementing and sharing of responsibility. Social development was carried out in accordance with the 4 strategic issues: upgrading the system of providing quality social development and welfare services, enhancing the capacity of the target population to be well-prepared for emerging changes, promoting an integrated approach and enhancing the capacity of quality networks, and developing the organization management towards becoming a learning organization. -

Meaning Relationship Between the Original Ban Chiang Pottery Pattern Stamps and Modern Auspicious Patterns

Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences 42 (2021) 439–446 Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences journal homepage: http://kjss.kasetsart.org Meaning relationship between the original Ban Chiang pottery pattern stamps and modern auspicious patterns Kanittha Ruangwannasaka,*, Sutthinee Sukkulb,†, Atchariya Suriyac, Krissada Dupandungd a Faculty of Humanities and Social science, Udon Thani Rajabhat University, Mueang, Udon Thani 41000, Thailand b Faculty of Architecture, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, Lat Krabang, Bangkok 10520, Thailand c Faculty of Technology, Udon Thani Rajabhat University, Mueang, Udon Thani 41000, Thailand d Faculty of Art and Industrial Design, Rajamangala University of Technology Isan, Mueang, Nakhon Ratchasima 30000, Thailand Article Info Abstract Article history: The study investigates the relationship between the original Ban Chiang patterns and Received 19 March 2020 Revised 27 April 2020 modern auspicious patterns in terms of meaning. The qualitative method was used to Accepted 5 May 2020 collect and analyze data. The sample or information source of Ban Chiang clay rollers Available online 30 April 2021 and Ban Chiang pottery pattern stamps includes a curator and a storekeeper of the Ban Chiang National Museum and a local person well-informed in Ban Chiang. Results Keywords: revealed that the Ban Chiang patterns are similar to modern auspicious patterns mainly Ban Chiang clay roller, in the use of animals; nature; fruits, trees, and flowers; objects, utensils, or artificial Ban Chiang pottery pattern stamp, designs; and belief as symbols. modern auspicious pattern, relationship © 2021 Kasetsart University. Introduction The researchers conducted interviews with sellers of goods and souvenirs to identify issues related to tourism and The Ministry of Tourism and Sports (2015) revealed that maximize the many tourist sites in Udon Thani and yearly one of the factors influencing tourism in Thailand that increasing number of tourists. -

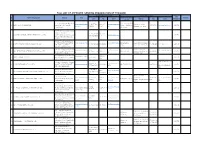

FULL LIST of APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION of THAILAND Approved Person in Charge of Training Contact Point in Japan Date No

FULL LIST OF APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION OF THAILAND Approved Person in charge of Training Contact Point in Japan date No. Name of Organization Address URL Name of Person in Remarks name TEL Email Address TEL Email (the date of Charge receipt) 10th ft. Social security., Ministry of Office of Labour Affair https://www.doe.go.th MR. KHATTIYA +662 245 [email protected] 3-14-6 kami - Osaki, 1 DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT Labour Mitr-Maitri Road, Din- in Japan (Mr.Saichon 03-5422-7014 [email protected] 2019/7/2 /overseas PANDECH 6708-9 om Shinagawa - ku Tokyo Daeng Bangkok Akanitvong) 259/333 2ND Floor Yangyuenwong Building, Sukhumvit 71 MR. PASSAPONG (66)-2-391- 2 J.J.S. BANGKOK DEVELOPMENT & MANPOWER CO., LTD. Road,Phrakhanongnua Sub-district, - [email protected] 2019/7/2 YANGYUENWONG 3499 Wattana District, Bangkok 10110 Thailand No.7,1ST FLOOR, SOI NAKNIWAT 57, NAKNIWAT ROAD, LADPRAO www.linkproplacement. [email protected] Ms. Suwutjittra Tokyo, Adachi Ku, Higashi 3 LINKPRO INTERNATIONAL PLACEMENT CO., LTD. MR. Korn Sakajai 080-6113525 090-7945-2494 [email protected] 2019/7/2 SUB-DISTRICT, LADPRAO net om Nawilai Ayase 1-15-19-102 Room DISTRICT, BANGKOK 10230 293/1,Mu 15,Nang-Lae Sub-district, 247-0071 Tamagawa, www.ainmanpower.co [email protected] [email protected] 4 ASIA INTERNATIONAL NETWORK MANPOWER CO., LTD. Muang Chiangrai District, Chiangrai Ms. Mayuree Jina 0918599777 Mr. Shoichi Saho Kamakura City, Kanagawa 080-3449-1607 2019/7/2 m .th h Province 57100 Thailand Prefecture, Japan 163/1 Nuanchan Rd,Nuanchan Sub- www.vincplacement.co +662 735 5 VINC PLACEMENT CO., LTD. -

LEARN and EARN How Schools Prepared Students to Seek out Decent Work

LEARN AND EARN How schools prepared students to seek out decent work 1 THE PROJECT’S OBJECTIVE: Teaching students entrepreneurial and vocational skills through actual income-earning enterprises and preparing them for a smoother school-to- work transition. Facilitating school-to work transition: Income generating in school-based activities and awareness raising THE INITIAL CHALLENGE: Research had revealed a large number of children in schools who combine education with hazardous work; they need to earn an income in order to stay in school or to help their family. But in the north-eastern Udon Thani province and the northern province of Chiang Rai, many students engage in work that has potential negative impact on their development, such as tapping rubber trees in the hours after midnight until dawn or working in markets at late hours. There was a need to convince them and their families they should do other work that allowed them to get the critical sleep that children need to develop appropriately. There also was a need to provide income-generating options to young students who were at risk of leaving school in order to work - the research indicated about 5,000 students in four districts of Udon Thani were verging on dropping out. Eliminating the Worst Forms of Child Labour in Thailand : Good Practices and Lessons Learned THE RESPONSE: Working children in agriculture, the service sector or in domestic labour were given opportunity to pursue recreational activities, non-formal education, career counselling, skills development and apprenticeships that suited their interests. THE PROCESS: The International Labour Organization’s International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour and its Project to Support National Action to Combat Child Labour and Its Worst Forms in Thailand (the ILO-IPEC project) worked with the Child and Youth Assembly of Udon Thani (CYA) to help teachers target 600 working or at-risk, students. -

Open Sangpenchan Msthesis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Geography CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS ON CASSAVA PRODUCTION IN NORTHEASTERN THAILAND A Thesis in Geography by Ratchanok Sangpenchan 2009 Ratchanok Sangpenchan Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2009 ii The thesis of Ratchanok Sangpenchan was reviewed and approved* by the following: Amy Glasmeier Professor of Geography Thesis Advisor William E. Easterling Professor of Geography Karl Zimmerer Head of the Department of Geography *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Analyses conducted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007) suggest that some regions of Southeast Asia will begin to experience warmer temperatures due to elevated CO2 concentrations. Since the projected change is expected to affect the agricultural sector, especially in the tropical climate zones, it is important to examine possible changes in crop yields and their bio-physiological responses to future climate conditions in these areas. This study employed a climate impact assessment to evaluate potential cassava root crop production in marginal areas of Northeast Thailand, using climate change projected by the CSIRO-Mk3 model for 2009–2038. The EPIC (Erosion Productivity Impact Calculator) crop model was then used to simulate cassava yield according to four scenarios based on combinations of CO2 fertilization effects scenarios (current CO2 level and 1% per year increase) and agricultural practice scenarios (with current practices and assumed future practices). Future practices are the result of assumed advances in agronomic technology that are likely to occur irrespective of climate change. They are not prompted by climate change per se, but rather by the broader demand for higher production levels. -

Transnational Economic Connectivity of the Vietnamese

Transnational Economic Connectivity of the Vietnamese Diaspora Community in Udon Thani Province, Thailand: Mirroring the ASEAN Economic Community 137 Transnational Economic Connectivity of the Introduction The transnational perspective in migration studies has gained popularity Vietnamese Diaspora Community in over the past two decades. Transnationalism is perceived as “multiple Udon Thani Province, Thailand: Mirroring ties and interactions linking people or institutions across the borders of 1 nation-states” (Vertovec, 1999: 447). Portes et al. (1999) categorized the ASEAN Economic Community three major forms of transnationalism: economic, political, and socio-cultural. Transnationalism is prevalent among diaspora groups Nguyen Thi Tu Anh whose consciousness is embedded in trans-state networks. The target Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand group of this research is the Vietnamese diaspora community settled in Email: [email protected] Udon Thani province, in the northeastern region (also known as Isan) Received: December 15, 2020 of Thailand. My work draws upon the idea that the construction of Revised: February 19, 2021 trans-border networks is a major activity conducted by “an ethno- Accepted: March 10, 2021 national diaspora” who “regard themselves as of the same ethno-national Abstract origin and permanently reside as minorities in one or several host This article is based on research concerning transnational economic connectivity countries” (Sheffer, 2003: 9, 10). established by the Vietnamese diaspora community in Udon Thani province in The use of the term “Vietnamese diaspora” in this study refers northeastern Thailand, a topic that has not yet received sufficient academic to those who hold Thai citizenship, have permanently settled in Udon attention. -

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received Bom 9 to 14 May 1980 — Notifications Reçues Du 9 Au 14 Mai 1980 C Cases — Cas

Wkty Epldem. Bec.: No. 20 -16 May 1980 — 150 — Relevé éptdém. hebd : N° 20 - 16 mal 1980 Kano State D elete — Supprimer: Bimi-Kudi : General Hospital Lagos State D elete — Supprimer: Marina: Port Health Office Niger State D elete — Supprimer: Mima: Health Office Bauchi State Insert — Insérer: Tafawa Belewa: Comprehensive Rural Health Centre Insert — Insérer: Borno State (title — titre) Gongola State Insert — Insérer: Garkida: General Hospital Kano State In se rt— Insérer: Bimi-Kudu: General Hospital Lagos State Insert — Insérer: Ikeja: Port Health Office Lagos: Port Health Office Niger State Insert — Insérer: Minna: Health Office Oyo State Insert — Insérer: Ibadan: Jericho Nursing Home Military Hospital Onireke Health Office The Polytechnic Health Centre State Health Office Epidemiological Unit University of Ibadan Health Services Ile-Ife: State Hospital University of Ife Health Centre Ilesha: Health Office Ogbomosho: Baptist Medical Centre Oshogbo : Health Office Oyo: Health Office DISEASES SUBJECT TO THE REGULATIONS — MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received bom 9 to 14 May 1980 — Notifications reçues du 9 au 14 mai 1980 C Cases — Cas ... Figures not yet received — Chiffres non encore disponibles D Deaths — Décès / Imported cases — Cas importés P t o n r Revised figures — Chifircs révisés A Airport — Aéroport s Suspect cases — Cas suspects CHOLERA — CHOLÉRA C D YELLOW FEVER — FIÈVRE JAUNE ZAMBIA — ZAMBIE 1-8.V Africa — Afrique Africa — Afrique / 4 0 C 0 C D \ 3r 0 CAMEROON. UNITED REP. OF 7-13JV MOZAMBIQUE 20-26J.V CAMEROUN, RÉP.-UNIE DU 5 2 2 Asia — Asie Cameroun Oriental 13-19.IV C D Diamaré Département N agaba....................... î 1 55 1 BURMA — BIRMANIE 27.1V-3.V Petté ...........................