Who's Counting?: an Institutional Analysis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clean Energy Transition

Leadership Forum on energy transition Forum Member Profiles Professor Ian Jacobs (Chair) President and Vice-Chancellor, UNSW Australia Ian came to Australia from the UK, where he had a distinguished career as a leading researcher in the area of women’s health and cancer, and in university leadership. Immediately prior to joining UNSW Ian was Vice President and Dean at the University of Manchester and Director of the Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, a partnership linking the University with six healthcare organisations involving over 36,000 staff. Ian is the Principal Investigator for the Cancer Research UK and Eve Appeal funded PROMISE (Prediction of Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Screening and Early Detection) programme and on several large multicentre clinical trials including the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer and the UK Familial Ovarian Cancer Screening Study. Ian established and chairs the Uganda Women’s Health Initiative, is founder and Medical Advisor to the Eve Appeal charity, a Patron of Safehands for Mothers, founder and non- Executive Director of Abcodia Ltd and patent holder of the ROCA (Risk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm). Mr Geoffrey Cousins AM President, Australian Conservation Foundation Geoff is an Australian community leader, businessman, environmental activist and writer. As an environmental activist he is best known for his successful campaigns to stop the Gunns pulp mill in Tasmania and the proposed Woodside gas hub in the Kimberley. Geoff’s distinguished business career has included Chief Executive roles in advertising and media and positions on a number of public company boards including PBL, the Seven Network, Hoyts Cinemas group, NM Rothschild & Sons Limited and Telstra. -

Community Connections University of Wollongong Special Supplement June 2011

Community Connections University of Wollongong Special Supplement June 2011 SHARE Student & Staff THOUGHTS YOUR UOW CHLOE HIGGINS: My happiest UOW memory is leaving my fi rst lecture and STORIES realising I am exactly where I want to be. KRISTIE LYNCH: My happiest UOW memory is sitting under the big tree near 60th anniversary time the duck pond sitting there eating, feeding the ducks and birds who were nearby, being surrounded by fellow University capsule captures history students. I felt quite content and had a sense of belonging. TIM BROWN: The Lecturer I remember The University of Wollongong (UOW) is building from UOW was Margaret Bond. She made an interactive digital time capsule to mark its 60th me enthusiastic about contract law, a very Anniversary. Throughout the year stories, videos rare quality! and images which paint a picture of campus life in 2011 will be collected and published on the 60th Anniversary website for future UOW generations to NICK MORRISON: The one piece of view. advice I would give a UOW fi rst year is UOW this year is celebrating the 60th anniversary to get to know the kids on campus. Your of the establishment in Wollongong in 1951 of a social life will quadruple overnight and you small divisional college outpost of what was then will start to feel at home at uni. called the NSW University of Technology (later the University of NSW). The college moved from Coniston to its current site in 1962, and became a JESSICA SHILLINGTON: The person I fully autonomous university in 1975. was happy to meet at UOW was Aeelee The theme of the 60th Anniversary is Share your Jun because I am not a fi nance student Story and aims to recognise the role staff, students,, and I passed. -

Download Booklet

Introductions General John Gowans lives on through his words. The Salvation Army on beyond the musicals. The 2015 edition of The Song Book of The world was deeply saddened when he was promoted to Glory in December Salvation Army includes 28 of them – and they continue to be sung 2012, but thank God for the legacy of song words that he left us. Through around the world. them he still speaks to inspire and challenge and encourage, and with this album we are invited to share in a further 23 jewels from this legacy. Commissioner Gisèle Gowans and I were grateful to The International Staff Songsters when the first volume of A Gowans Legacy was recorded It is no secret that I set most of John’s song lyrics to music – and that in 2016. It seems that our appreciation has been shared by many, for explains why all but four of the songs included on this album are with that album has become a best-seller, and we are pleased that it is now music by me. being followed by this second volume. John and I hardly knew each other when in 1966 we were asked to form For my own part, I have enjoyed creating songster arrangements a creative partnership. The National Youth Secretary, Brigadier Denis for a number of the songs on the album for which the original stage Hunter, had called a small group together to discuss the possibility of a arrangement did not lend itself for recording. Getting immersed in that musical for Youth Year 1968 and ideas had flowed. -

Divisional Newsletter - 1212 Decemberdecember 20122012

Divisional Newsletter - 1212 DecemberDecember 20122012 Dear friends, We take this opportunity to thank you for all the extra time and effort you and your people are giving to MAJORS NORM AND ISABEL BECKETT share the true meaning of Christmas. As you proclaim Training Principal and Education Officer, the Christmas message through music, carols and Sweden and Latvia Territory preaching, and share the joy of giving hampers, toys WOODPORT RETIREMENT VILLAGE, NSW and meals, we pray that you will take time to sit in Alison Scott, Captain Jo-Anne Chant, Major wonder at the indescribable love of Christ our Christine Mayes and team Saviour. BURWOOD CORPS, NSW Captain Rhombus Ning and Lieutenants We share with you the words of the following song Marcus and Ji-Sook Wunderlich used at Fairhaven Carols last Sunday night. CAMPBELLTOWN CORPS, NSW When Christ was born the angel voices thundered Majors Garry and Susanne Cox Glory to God and peace to men on earth NAMBUCCA RIVER CORPS, NSW And shepherds in the fields looked on and wondered Captains John and Nicole Viles The marvel of the Saviour’s lowly birth. OASIS YOUTH CENTRE WYONG, NSW When men of wisdom saw a star before them They knew the sign foretold the Saviours birth DECEMBER From lands afar they came in awe to wonder 14 End Queensland School term That God Himself should come to men on earth. 16 Divisional Candidates Farewell 21 End NSW School term 25 Christmas Day That God should come to men, born in a manger 26 Boxing Day I can but ponder such humility JANUARY That He now reigns in glory and in splendour 1 New Years Day I can but wonder of His love for me. -

A Distance Education Program for the Salvation Army College for Officer Training

Please HONOR the copyright of these documents by not retransmitting or making any additional copies in any form (Except for private personal use). We appreciate your respectful cooperation. ___________________________ Theological Research Exchange Network (TREN) P.O. Box 30183 Portland, Oregon 97294 USA Website: www.tren.com E-mail: [email protected] Phone# 1-800-334-8736 ___________________________ ATTENTION CATALOGING LIBRARIANS TREN ID# Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) MARC Record # Digital Object Identification DOI # Ministry Focus Paper Approval Sheet This ministry focus paper entitled A DISTANCE EDUCATION PROGRAM FOR THE SALVATION COLLEGE FOR OFFICER TRAINING Written by BRIAN M. SAUNDERS and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry has been accepted by the Faculty of Fuller Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: _____________________________________ Kurt Fredrickson oDate Received: November 30, 2012 A DISTANCE EDUCATION PROGRAM FOR THE SALVATION ARMY COLLEGE FOR OFFICER TRAINING A MINISTRY FOCUS PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY BRIAN M. SAUNDERS NOVEMBER 2012 ABSTRACT A Distance Education Program for The Salvation Army College for Officer Training Brian M. Saunders Doctor of Ministry School of Theology, Fuller Theological Seminary 2012 The goal of this paper is to develop a distance education program for The Salvation Army’s USA Western Territory. The Salvation Army’s current clergy education program, a two-year residential college located in Southern California, is somewhat limited in that it excludes those who may not be able to relocate to Los Angeles. -

A Theology of Ecclesial Charisms with Special Reference to the Paulist Fathers and the Salvation Army

A Theology of Ecclesial Charisms with Special Reference to the Paulist Fathers and The Salvation Army by James Edwin Pedlar A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Department of Theology of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College. © Copyright by James E. Pedlar 2013 A Theology of Ecclesial Charisms With Special Reference to the Paulist Fathers and The Salvation Army James Edwin Pedlar Doctor of Philosophy in Theology University of St. Michael’s College 2013 ABSTRACT This project proposes a theology of “group charisms” and explores the implications of this concept for the question of the limits of legitimate diversity in the Church. The central claim of the essay is that a theology of ecclesial charisms can account for legitimately diverse specialized vocational movements in the Church, but it cannot account for a legitimate diversity of separated churches. The first major section of the argument presents a constructive theology of ecclesial charisms. The scriptural concept of charism is identified as referring to diverse vocational gifts of grace which are given to persons in the Church, and have an interdependent, provisional, and sacrificial character. Next, the relationship between charism and institution is specified as one of interdependence-in-distinction. Charisms are then identified as potentially giving rise to a multiplicity of diverse, vocationally-specialized movements in the Church, which are normatively distinguished from churches. The constructive argument concludes by claiming that the theology of ecclesial charisms as proposed supports visible, historic, organic unity. -

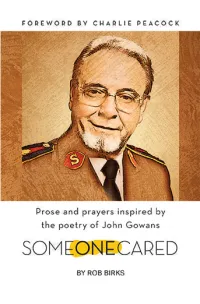

Someone Cared

SOMEONE CARED Prose and Prayers Inspired by the Poetry of John Gowans by Rob Birks SOMEONE CARED Rob Birks 2014 Frontier Press All rights reserved. Except for fair dealing permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any means without written permission from the publisher. Birks, Rob SOMEONE CARED December 2014 Scripture references used in this text are from The Holy Bible, New Inter- national Version, New Living Translation, New American Standard, Ampli- fied Bible, The Living Bible. THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. The King James Version is public domain in the United States. Scripture taken from The Message. Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2002. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group. Copyright © The Salvation Army USA Western Territory ISBN 978-0-9908776-1-5 Printed in the United States For Stacy Sharing poetry introduced our hearts to each other. I couldn’t be more grateful. I love you more than dreams and poetry. More than laughter, more than tears, more than mystery. I love you more than rhythm, more than song I love you more with every breath I draw. —T Bone Burnett iii There is nothing quite like walking through an art gallery with a docent, or the curator himself. This is the feeling I get as I read Ma- jor Robert Birks’ beautiful unveiling of the poetry of John Gowans. He is an informed, inspired guide whose joy regarding the poet’s work is contagious. -

Journal of Aggressive Christianity

JOURNAL OF AGGRESSIVE CHRISTIANITY Issue 81, October – November 2012 Copyright © 2012 Journal of Aggressive Christianity Journal of Aggressive Christianity, Issue 81, October – November 2012 2 In This Issue JOURNAL OF AGGRESSIVE CHRISTIANITY Issue 81, October - November 2012 Editorial Introduction page 3 Editor, Major Stephen Court 100 Most Influential Salvationists page 4 Colonel Richard Munn Holiness and Other Pertinent Matters page 7 Erin Wikle Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry page 13 Captain Rob Reardon An Innovative Salvation Army page 21 Lieutenant Peter Brookshaw What Now? page 23 Colonel David Gruer Trapped page 29 Tina Laforce A Great Commission? page 38 Lieutenant Xander Coleman How Lost are the Lost? page 42 Major Howard Webber A Living Sacrifice page 44 CSM Tim Taylor What Might Have Been? page 49 Commissioner Wesley Harris William and Catherine Booth's Mobilisation of an Army of all Believers Through Partnered Ministry page 50 Jonathan Evans Journal of Aggressive Christianity, Issue 81, October – November 2012 3 Editorial Introduction by Editor, Major Stephen Court Welcome to JAC81. You might reasonably ask how we can match the weighty JAC80. This is our considered response. Colonel Richard Munn (ICO) updates the first JAC 100 – Most Influential Salvationists list from 2007. This is his personal take on the subject. Soldier Erin Wikle, pioneering a corps in USA Southern Territory, writes Holiness and Other Pertinent Matters. Erin did some very interesting research into holiness and discipleship in the USA Western Territory and shares her results. Captain Rob Reardon (USN) gives his thoughtful take on Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry from The Salvation Army’s perspective. -

2016 Business Mission Report

10th Australian Business Mission to Europe Zurich, Bern, Brussels, Helsinki 26 June - 1 July 2016 Mission Report Supported by EABC Major Partner: (Executive Summary) Introduction The EABC Australian Business Mission to Europe is undertaken each year as an initiative to strengthen bilateral relationships with European leaders, institutions, officials, peak business groups and policy organisations. The Missions travel to Brussels as the political and administrative capital of the European Union, and to other political and commercial capitals in Europe. Since 2006, EABC delegations have travelled to Berlin, Bratislava, Budapest, Copenhagen, Frankfurt, Geneva, Hamburg, Istanbul, London, Madrid, Milan, Munich, Paris, Rotterdam, Stockholm, Strasbourg, The Hague, Toulouse, Venice, Vienna and Warsaw. The visits provide opportunities for senior Australian business representatives to engage in dialogue on issues including policy responses to the global financial crisis, economic and fiscal policy, banking and financial services, foreign and security policy, trade, competition, energy and climate change policy, infrastructure, research and innovation. The Missions also provide a valuable opportunity for Australian business leaders to work with Australian Government representatives in Europe - principally with Australian Embassies and Austrade offices - to profile Australia’s economic credentials and capabilities and promote opportunities for European investment in Australia. Mission Leader & Endorsements The Council was delighted to have the leadership and participation of EABC Chairman and former Premier of New South Wales, the Hon Nick Greiner AC, for the 2016 Mission to Zurich, Bern, Brussels and Helsinki. The Prime Minister of Australia, the Hon Malcolm Turnbull MP, also endorsed the mission as an important initiative to foster greater economic relations between Australia and Europe. -

8Th Australian Business Mission to Europe

EABC Delegation with Governor-General Quentin Bryce and European Council President Herman van Rompuy, Brussels, 2013 8th Australian Business Mission to Europe London 26 - 27 June 2014 Warsaw, Brussels & Madrid 29 June - 4 July 2014 Delegation Member & Organisational Profiles EABC Australian Business Mission to Europe London, Warsaw, Brussels, Madrid 26 June - 4 July 2014 Delegation Members Alastair Walton (EABC Chairman) Chairman, BKK Partners former Chairman, Goldman Sachs Australia; former Member, Financial Services Advisory Council (Australian Government) Jason Collins (EABC CEO) Chief Executive Officer, European Australian Business Council; Chairman, European Business Organisations Worldwide; Member, NSW Export & Investment Advisory Panel (NSW Government) Philip Aiken AM (EABC Corporate Council) Chairman, AVEVA Group; Director, National Grid; Director, Newcrest Mining; Director, Essar Energy; Chairman, Australia Day Foundation UK; former Group President Energy, BHP Billiton Angus Armour (EABC Board) Deputy Director General, NSW Trade & Investment (NSW Government); former CEO, Export Finance and Insurance Corporation (Australian Government); former Chairman, The Berne Union Peter Bond (EABC Board) Chief Executive Officer & Managing Director, Linc Energy Jillian Broadbent AO (EABC Corporate Council) Chairman, Clean Energy Finance Corporation; Director, Woolworths Limited; Chancellor, University of Wollongong; former Board Member, Reserve Bank of Australia (Australian Government) Michael Cameron (EABC Board) Chief Executive Officer & -

Aspects of Leadership in the Salvation Army History Salv 0670 / Hist 0670

Tyndale Seminary Course Syllabus SPRING/SUMMER 2020 ASPECTS OF LEADERSHIP IN THE SALVATION ARMY HISTORY SALV 0670 / HIST 0670 MAY 4 – JULY 24, 2020 ONLINE INSTRUCTOR: MATTHEW SEAMAN, PHD Tel: +61-438-613-548 (Australia) Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Access your course materials at the start of the course, or copy this URL into your browser http://myboothonline.boothuc.ca. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION This course traces the nature and development of leadership in The Salvation Army, exploring how it relates to leadership in general and to the Church in particular, and asking questions about the challenges the Army’s leadership model faces in the contemporary world. It should be clear that this does not purport to be a course inculcating the principles and best practice of leadership in general, although the student may well draw conclusions about these matters from a study of the Salvation Army’s history, with which this course is concerned. Areas reviewed in this course on aspects of leadership in The Salvation Army (a) The evolution of the function and status of Salvation Army officers in the context of the Army and of church as a whole. (b) The leadership of women, as a parallel debate. To what degree were/are women equally officers? 1 Revised: 2 March 2020 (c) The extent to which The Salvation Army is able to integrate authoritarian, consultative and participative modes of leadership. What are the strengths and weaknesses of each? How far is leadership ability the decisive factor and how determining is the structural form within which it is exercised? II. -

Readings, Research, and Resources

Readings, Research, and Resources 2011-12 Topics ©2011 FUTURE PROBLEM SOLVING PROGRAM INTERNATIONAL, INC. All rights reserved. Future Problem Solving Program International, Inc. in an effort to provide practical and economical educational materials has designated this publication a “reproducible book.” The notebook format has been chosen for this publication so that the user can easily make copies. The purchase of this book grants the individual purchaser the right to print the pages contained herein and make sufficient copies of said pages for use by the FPS students of a single teacher or single FPS coach. Any other use requires written permission from Future Problem Solving Program International, Inc. Purchase does not permit reproduction of any part of the book for an entire school, special programs, school district or school system, or for commercial use. Such use is strictly prohibited. Any violation to this copyright will result in a charge of no less than $500 per incidence. Readings, Research, and Resources For the 2011-12 topics: All in a Day’s Work Resources Coral Reefs Appendix Human Rights Trade Barriers Readings, Research, and Resources 2011-12 ©Future Problem Solving Program International, Inc. ©2011 FUTURE PROBLEM SOLVING PROGRAM INTERNATIONAL, INC. All rights reserved. Future Problem Solving Program International, Inc. in an effort to provide practical and economical educational materials has designated this publication a “reproducible book.” The notebook format has been chosen for this publication so that the user can easily make copies. The purchase of this book grants the individual purchaser the right to print the pages contained herein and make sufficient copies of said pages for use by the FPS students of singlea teacher or single FPS coach.