Aya Hamada Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcribing Couperin's Preludes À La

DOI: 10.32063/0509 TRANSCRIBING COUPERIN’S PRELUDES À LA D’ANGLEBERT: A JOURNEY INTO THE CREATIVE PROVESSES OF THE 17TH-CENTURY QUASI- IMPROVISATORY TRADITION David Chung David Chung, harpsichordist and musicologist, performs extensively on the harpsichord in cities across Europe, North America and Asia. He has appeared in the Festival d’Ile-de-France, Geelvinck Fortepiano Festival, Cambridge Early Keyboard Festival, Hong Kong International Chamber Music Festival, Le French May Arts Festival and Hong Kong New Vision Arts Festival. David received his education at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the Royal Academy of Music, London and Churchill College, Cambridge. His scholarly contributions include articles and reviews in journals such as Early Music, Early Keyboard Journal, Eighteenth- Century Music, Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music, Music and Letters, Notes, and Revue de musicologie. His edition of nearly 250 keyboard arrangements of Jean-Baptiste Lully’s music is available from the Web Library of Seventeenth-Century Music (www.sscm- wlscm.org). He is currently Professor of Music at Hong Kong Baptist University. Abstract: Transcribing Couperin’s Preludes à la D’Anglebert: a Journey into the Creative processes of the 17th century Quasi-improvisatory Tradition The interpretation of the unmeasured preludes by Louis Couperin is contentious, owing to their rhythmically-free notation. Couperin’s system of notation is unique to him, but the complex system of lines that he apparently invented contains both ambiguities and inconsistencies between the two sources of this repertory. Modern editors are sometimes sharply split on whether lines are curved or straight, where they begin and end, and whether notes are joined or separated by lines. -

Salon Musical Au Xviiie Siècle

Journées européennes du patrimoine Salon musical au XVIIIe siècle À l’écoute d’un mystérieux manuscrit de clavecin Samedi 14 septembre 2013 à 18h15 Archives des Yvelines Sommaire Programme p. 3 Le manuscrit p. 4 Les compositeurs p. 8 Un salon musical au XVIIIe siècle p. 10 Marie Vallin p. 11 Informations pratiques p.12 Concert donné à l’occasion des Journées européennes du patrimoine avec le concours du Conservatoire à rayonnement régional de Versailles et du Musée de la Toile de Jouy Conception et rédaction : Céline PAGNAC et Marie VALLIN - Conception graphique : Mathilde LAINEZ Ill. couverture, crédits : Archives des Yvelines Programme Jacques Duphly (1715-1789) La De Vatre La Félix La Lanza Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757) Pièce sans titre [Allegro] Allegro Anonyme L’orageuse Jean-Baptiste Barrière (1707-1747) Grave-Prestissimo, Allegro, Aria Domenico Alberti (v. 1710-1740) Allegro moderato (1er mouvement de la Sonate II) Anonyme Le réveil matin Antoine Forqueray (1672-1745) La Mandoline : M. Vallin 3 Crédit photo Le manuscrit Un document atypique May (avec violon), Menuet. Mais aux Archives d’autres pièces françaises sont aussi présentes : La Mandoline ux Archives des Yvelines se d’Antoine Forqueray (1672-1745), trouve, classé sous la cote A Les Ciclopes [sic] et la Pantomime 1F207, un recueil manuscrit de de Pigmalion [sic] du célèbre pièces de clavecin. Il suscite de Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764). nombreuses interrogations quant L’Italie est aussi représentée, avec à sa provenance, sa datation, au moins 5 sonates de Domenico son propriétaire. Il semble difficile Scarlatti (1685-1757), une sonate de remonter à ses origines : il n’est de Domenico Alberti (v. -

The Baroque Offertoire : Apotheosis of the French Organ Art

The Baroque Offertoire : Apotheosis of the French Organ Art By Copyright 2016 Song Yi Park Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Michael Bauer ________________________________ Dr. James Higdon ________________________________ Dr. Colin Roust ________________________________ Dr. Bradley Osborn ________________________________ Professor Jerel Hildig Date Defended: November 1, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Song Yi Park certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Baroque Offertoire : Apotheosis of the French Organ Art ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Michael Bauer Date approved: November 1, 2016 ii Abstract During the French Baroque period, the function of the organ was primarily to serve the liturgy. It was an integral part of both Mass and the office of Vespers. Throughout these liturgies the organ functioned in alteration with vocal music, including Gregorian chant, choral repertoire, and fauxbourdon. The longest, most glorious organ music occurred at the time of the offertory of the Mass. The Offertoire was the place where French composers could develop musical ideas over a longer stretch of time and use the full resources of the French Classic Grand jeu , the most colorful registration on the French Baroque organ. This document will survey Offertoire movements by French Baroque composers. I will begin with an introductory discussion of the role of the offertory in the Mass and the alternatim plan in use during the French Baroque era. Following this I will look at the tonal resources of the French organ as they are incorporated into French Offertoire movements. -

A Study of Ravel's Le Tombeau De Couperin

SYNTHESIS OF TRADITION AND INNOVATION: A STUDY OF RAVEL’S LE TOMBEAU DE COUPERIN BY CHIH-YI CHEN Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University MAY, 2013 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music ______________________________________________ Luba-Edlina Dubinsky, Research Director and Chair ____________________________________________ Jean-Louis Haguenauer ____________________________________________ Karen Shaw ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my tremendous gratitude to several individuals without whose support I would not have been able to complete this essay and conclude my long pursuit of the Doctor of Music degree. Firstly, I would like to thank my committee chair, Professor Luba Edlina-Dubinsky, for her musical inspirations, artistry, and devotion in teaching. Her passion for music and her belief in me are what motivated me to begin this journey. I would like to thank my committee members, Professor Jean-Louis Haguenauer and Dr. Karen Shaw, for their continuous supervision and never-ending encouragement that helped me along the way. I also would like to thank Professor Evelyne Brancart, who was on my committee in the earlier part of my study, for her unceasing support and wisdom. I have learned so much from each one of you. Additionally, I would like to thank Professor Mimi Zweig and the entire Indiana University String Academy, for their unconditional friendship and love. They have become my family and home away from home, and without them I would not have been where I am today. -

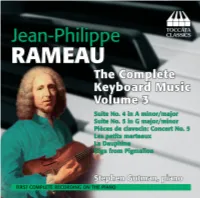

Toccata Classics TOCC0052 Notes

RAMEAU ON THE PIANO, VOLUME THREE 1 by Graham Sadler The two suites recorded on this disc are from the Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin of 1729 or 1730, Rameau’s final collection of solo keyboard music.2 Like those of his Pièces de clavessin (1724), they are contrasted both in tonality and character. The Suite in A minor and major is dominated by dances and includes only three character pieces, whereas the Suite in G major and minor consists almost exclusively of pieces with character titles. In its make-up if not its style, the latter thus follows the example of François Couperin, whose first three books of pièces de clavecin (1713, 1717 and 1722) had established the vogue for descriptive pieces. In that sense, Rameau may be regarded as somewhat conservative in devoting half of his two mature solo collections to suites of the more traditional type. Suite No. 4 in A minor and major Conservative they may be, but the dance movements of the Nouvelles suites are among the most highly P developed in the repertory, the first two particularly so. The Allemande 1 unfolds with an effortless grace, its unerring sense of direction reinforced by the many sequential passages. At the end of both sections, the duple semiquaver motion gives way unexpectedly to triplet motion, providing a memorable ‘rhyme’ to the two parts of the movement. The Courante 2, more than twice as long as its predecessors in Rameau’s output, displays a technical sophistication without parallel in the clavecin repertory. Three themes interlock in mainly three- part counterpoint – a bold motif in rising fourths, and two accompanying figures in continuous quavers, the one in sinuous stepwise movement, the other comprising cascading arpeggios. -

MOZARTEUM BAROQUE MASTERCLASSES Concerto Degli

International Festival & Summer Academy 2021 60 CONCERTI, FOCUS SU STEVE REICH con Salvatore Accardo · Antonio Pappano · Lilya Zilberstein · Ilya Gringolts Patrick Gallois · Alessandro Carbonare · David Krakauer · Antonio Meneses DavidSABATO Geringas · Bruno 4 SETTEMBRE Giuranna · Ivo Nilsson - ORE· Mathilde 21,15 Barthélémy AntonioCHIESA Caggiano ·DI Christian S. AGOSTINO, Schmitt · Clive Greensmith SIENA · Quartetto Prometeo Marcello Gatti · Florian Birsak · Alfredo Bernardini · Vittorio Ghielmi Roberto Prosseda · Eliot Fisk · Andreas Scholl e tanti altri e con Orchestra dell’Accademia di Santa Cecilia · Orchestra della Toscana Coro Della Cattedrale Di SienaCHIGIANA “Guido Chigi Saracini - MOZARTEUM” . BAROQUE MASTERCLASSES 28 CORSI E SEMINARI NUOVA COLLABORAZIONEConcerto CON degli Allievi CHIGIANA-MOZARTEUM BAROQUE MASTERCLASSES docenti ANDREAS SCHOLL canto barocco MARCELLO GATTI flauto traversiere ALFREDO BERNARDINI oboe barocco VITTORIO GHIELMI viola da gamba FLORIAN BIRSAK clavicembalo e basso continuo maestri collaboratori al clavicembalo Alexandra Filatova Andreas Gilger Gabriele Levi François Couperin Parigi 1668 - Parigi 1733 da Les Nations (1726) Quatrième Ordre “La Piemontoise” Martino Arosio flauto traversiere (Italia) Micaela Baldwin flauto traversiere (Italia / Perù) Laura Alvarado Diaz oboe (Colombia) Amadeo Castille oboe (Francia) Alice Trocellier viola da gamba (Francia) Raimondo Mazzon clavicembalo (Italia) Georg Friedrich Händel Halle 1685 - Londra 1759 da Orlando (1733) Amore è qual vento Rui Hoshina soprano (Giappone) -

Download Booklet

95779 The viola da gamba (or ‘leg-viol’) is so named because it is held between the legs. All the members of the 17th century, that the capabilities of the gamba as a solo instrument were most fully realised, of the viol family were similarly played in an upright position. The viola da gamba seems to especially in the works of Marin Marais and Antoine Forqueray (see below, CD7–13). have descended more directly from the medieval fiddle (known during the Middle Ages and early Born in London, John Dowland (1563–1626) became one of the most celebrated English Renaissance by such names as ffythele, ffidil, fiele or fithele) than the violin, but it is clear that composers of his day. His Lachrimæ, or Seaven Teares figured in Seaven Passionate Pavans were both violin and gamba families became established at about the same time, in the 16th century. published in London in 1604 when he was employed as lutenist at the court of the Danish King The differences in the gamba’s proportions, when compared with the violin family, may be Christian IV. These seven pavans are variations on a theme, the Lachrimae pavan, derived from summarised thus – a shorter sound box in relation to the length of the strings, wider ribs and a flat Dowland’s song Flow my tears. In his dedication Dowland observes that ‘The teares which Musicke back. Other ways in which the gamba differs from the violin include its six strings (later a seventh weeps [are not] always in sorrow but sometime in joy and gladnesse’. -

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano A Performance Edition with Commentary D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of the The Ohio State University By Antoine Terrell Clark, M. M. Music Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Approved By James Pyne, Co-Advisor ______________________ Co-Advisor Lois Rosow, Co-Advisor ______________________ Paul Robinson Co-Advisor Copyright by Antoine Terrell Clark 2009 Abstract Late Baroque works for string instruments are presented in performing editions for clarinet and piano: Giuseppe Tartini, Sonata in G Minor for Violin, and Violoncello or Harpsichord, op.1, no. 10, “Didone abbandonata”; Georg Philipp Telemann, Sonata in G Minor for Violin and Harpsichord, Twv 41:g1, and Sonata in D Major for Solo Viola da Gamba, Twv 40:1; Marin Marais, Les Folies d’ Espagne from Pièces de viole , Book 2; and Johann Sebastian Bach, Violoncello Suite No.1, BWV 1007. Understanding the capabilities of the string instruments is essential for sensitively translating the music to a clarinet idiom. Transcription issues confronted in creating this edition include matters of performance practice, range, notational inconsistencies in the sources, and instrumental idiom. ii Acknowledgements Special thanks is given to the following people for their assistance with my document: my doctoral committee members, Professors James Pyne, whose excellent clarinet instruction and knowledge enhanced my performance and interpretation of these works; Lois Rosow, whose patience, knowledge, and editorial wonders guided me in the creation of this document; and Paul Robinson and Robert Sorton, for helpful conversations about baroque music; Professor Kia-Hui Tan, for providing insight into baroque violin performance practice; David F. -

Du Clavecin À La Harpe

UNIVERSITÉ PARIS–SORBONNE ÉCOLE DOCTORALE V « CONCEPTS ET LANGAGES » Patrimoines et langages musicaux CONSERVATOIRE NATIONAL SUPÉRIEUR DE MUSIQUE ET DE DANSE DE PARIS THÈSE Pour l’obtention du grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ PARIS-SORBONNE Discipline / Spécialité : Musique Recherche et Pratique Présentée et soutenue par : Constance Luzzati Le 20 novembre 2014 Du clavecin à la harpe Transcription du répertoire français du XVIIIe siècle Sous la direction de : Madame Raphaëlle Legrand, professeur à l’université de Paris IV – Sorbonne Monsieur Kenneth Weiss, claveciniste, chef d’orchestre, professeur au CNSMDP JURY : Madame Violaine Anger, maître de conférence habilité à diriger des recherches à l’Université d’Evry-Val-d’Essonne Monsieur Jean-Pierre Bartoli, professeur à l’Université Paris IV – Sorbonne Monsieur Philippe Brandeis, directeur des études musicales et de la recherche au CNSMDP Madame Raphaëlle Legrand, professeur à l’Université Paris IV – Sorbonne Madame Isabelle Moretti, harpiste, professeur au CNSMDP Monsieur Bertrand Porot, professeur à l’Université de Reims Monsieur Kenneth Weiss, claveciniste, chef d’orchestre, professeur au CNSMDP 1 2 Le répertoire original pour harpe est relativement restreint. Deux voies permettent de concourir à son accroissement : la création contemporaine d’une part, et la transcription d’autre part. La présente étude interroge le rapport entre les habitus anciens et une pratique actuelle de transcription, depuis le répertoire de clavecin français du XVIIIe siècle vers la harpe. La transcription est ici considérée comme une pratique non notée qui relève de l’interprétation, et qui partage avec celle-ci, comme avec la traduction, des problématiques fondamentales en apparence antinomiques : esprit et lettre, idiomatisme et fidélité. -

| 216.302.8404 “An Early Music Group with an Avant-Garde Appetite.” — the New York Times

“CONCERTS AND RECORDINGS“ BY LES DÉLICES ARE JOURNEYS OF DISCOVERY.” — NEW YORK TIMES www.lesdelices.org | 216.302.8404 “AN EARLY MUSIC GROUP WITH AN AVANT-GARDE APPETITE.” — THE NEW YORK TIMES “FOR SHEER STYLE AND TECHNIQUE, LES DÉLICES REMAINS ONE OF THE FINEST BAROQUE ENSEMBLES AROUND TODAY.” — FANFARE “THE MEMBERS OF LES DÉLICES ARE FIRST CLASS MUSICIANS, THE ENSEMBLE Les Délices (pronounced Lay day-lease) explores the dramatic potential PLAYING IS IRREPROACHABLE, AND THE and emotional resonance of long-forgotten music. Founded by QUALITY OF THE PIECES IS THE VERY baroque oboist Debra Nagy in 2009, Les Délices has established a FINEST.” reputation for their unique programs that are “thematically concise, — EARLY MUSIC AMERICA MAGAZINE richly expressive, and featuring composers few people have heard of ” (NYTimes). The group’s debut CD was named one of the "Top “DARING PROGRAMMING, PRESENTED Ten Early Music Discoveries of 2009" (NPR's Harmonia), and their BOTH WITH CONVICTION AND MASTERY.” performances have been called "a beguiling experience" (Cleveland — CLEVELANDCLASSICAL.COM Plain Dealer), "astonishing" (ClevelandClassical.com), and "first class" (Early Music America Magazine). Since their sold-out New “THE CENTURIES ROLL AWAY WHEN York debut at the Frick Collection, highlights of Les Délices’ touring THE MEMBERS OF LES DÉLICES BRING activites include Music Before 1800, Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner THIS LONG-EXISTING MUSIC TO Museum, San Francisco Early Music Society, the Yale Collection of COMMUNICATIVE AND SPARKLING LIFE.” Musical Instruments, and Columbia University’s Miller Theater. Les — CLASSICAL SOURCE (UK) Délices also presents its own annual four-concert series in Cleveland art galleries and at Plymouth Church in Shaker Heights, OH, where the group is Artist in Residence. -

Louis Couperin Suites Et Pavane

LOUIS COUPERIN SUITES ET PAVANE SKIP SEMPÉ MENU TRACKLIST TEXTE EN FRANÇAIS ENGLISH TEXT DEUTSCH KOMMENTAR REPÈRES / LANDMARKS / EINIGE DATEN ALPHA COLLECTION 34 SUITES ET PAVANE LOUIS COUPERIN (c.1626-1661) SUITE DE PIÈCES IN F 1 PRÉLUDE 2’25 2 COURANTE 0’58 3 SARABANDE 1’51 SUITE DE PIÈCES IN A 4 PRÉLUDE À L’IMITATION DE MONSIEUR FROBERGER 5’44 5 ALLEMANDE L’AMIABLE 3’05 6 COURANTE 0’55 7 COURANTE 1’50 8 PAVANE IN F SHARP MINOR 6’08 SUITE DE PIÈCES IN D PRÉLUDE 4’54 9 10 COURANTE 1’08 11 SARABANDE 2’54 12 CANARIES 0’59 SUITE DE PIÈCES IN A 13 PRÉLUDE ‘LE SOLIGNI’ (MARIN MARAIS) 3’31 14 SARABANDE 2’55 15 LA PIÉMONTOISE 1’24 MENU SUITES ET PAVANE SUITE DE PIÈCES IN F LOUIS COUPERIN (c.1626-1661) 16 PRÉLUDE 1’32 17 ALLEMANDE GRAVE 3’19 18 TOMBEAU DE MONSIEUR BLANCROCHER 6’24 19 GAILLARDE 1’37 SUITE DE PIÈCES IN C 20 PRÉLUDE 3’03 21 ALLEMANDE 2’32 22 COURANTE 1’15 23 SARABANDE 1’46 24 SARABANDE IN G 2’20 25 SARABANDE 2’26 26 TOMBEAU FAIT À PARIS SUR LA MORT 3’30 DE MONSIEUR BLANCHEROCHE (J.-J. FROBERGER) 27 GIGUE 1’31 28 PASSACAILLE 6’01 TOTAL TIME: 78’42 SKIP SEMPÉ harpsichord Bruce Kennedy, after a French model, 1985 tuning by Jean-François Brun Photos p. 8-9 : Jardin des Plantes, Paris, (1636) by Federic Scalberge, Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, © BnF, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image BnF. -

Chambonnières As Inspirer of the French Baroque Organ Style

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1977 The decisive turn : Chambonnières as inspirer of the French baroque organ style Rodney Craig Atkinson University of the Pacific Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Atkinson, Rodney Craig. (1977). The decisive turn : Chambonnières as inspirer of the French baroque organ style. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/1928 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - ;=;----------- THE DECISIVE TURN: CHAMBONNIERES' AS INSPIRER OF THE FRENCH BAROQUE ORGAN STYLE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of the Pacific r -- rc·-t:::---'--=-=----- ___:__:::_ !'~ ', ~- In Partial Fulfillment ' of the Requirements for the Degree Master· of Arts ,' by Rodney Craig Atkinson May 1977 --------=- - ' This thesis, written and submitted by is approved for recommendation to the Committee on Graduate Studies, University of the Pacific. Department Chairman or Dean: ~4_,ZiL Chairman ~> I Dated C?id:ctfjl:?~ /7 77 v (( =--~~----= ~-- p - ~-- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Appreciation is extended to Dr. David S. Goedecke for his guidance and suggestions. Loving appreciation goes to my parents, Dr. and Mrs. Herbert Atkinson, whose encouragement and support were responsible for the com pletion of this thesis. i i TABLE OF CONTENTS ::,:;; __ Page AC KNOW LED G~1 ENT S it LIST OF EXAMPLES v Chapter 1.