Windows Into Mississippi's Geologic Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plusinside Senti18 Cmufilmfest15

Pittsburgh Opera stages one of the great war horses 12 PLUSINSIDE SENTI 18 CMU FILM FEST 15 ‘BLOODLINE’ 23 WE-2 +=??B/<C(@ +,B?*(2.)??) & THURSDAY, MARCH 19, 2015 & WWW.POST-GAZETTE.COM Weekend Editor: Scott Mervis How to get listed in the Weekend Guide: Information should be sent to us two weeks prior to publication. [email protected] Send a press release, letter or flier that includes the type of event, date, address, time and phone num- Associate Editor: Karen Carlin ber of venue to: Weekend Guide, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 34 Blvd. of the Allies, Pittsburgh 15222. Or fax THE HOT LIST [email protected] to: 412-263-1313. Sorry, we can’t take listings by phone. Email: [email protected] If you cannot send your event two weeks before publication or have late material to submit, you can post Cover design by Dan Marsula your information directly to the Post-Gazette website at http://events.post-gazette.com. » 10 Music » 14 On the Stage » 15 On Film » 18 On the Table » 23 On the Tube Jeff Mattson of Dark Star City Theatre presents the Review of “Master Review of Senti; Munch Rob Owen reviews the new Orchestra gets on board for comedy “Oblivion” by Carly Builder,”opening CMU’s film goes to Circolo. Netflix drama “Bloodline.” the annual D-Jam show. Mensch. festival; festival schedule. ALL WEEKEND SUNDAY Baroque Coffee House Big Trace Johann Sebastian Bach used to spend his Friday evenings Trace Adkins, who has done many a gig opening for Toby at Zimmermann’s Coffee House in Leipzig, Germany, where he Keith, headlines the Palace Theatre in Greensburg Sunday. -

Unit-V Evolution of Horse

UNIT-V EVOLUTION OF HORSE Horses (Equus) are odd-toed hooped mammals belong- ing to the order Perissodactyla. Horse evolution is a straight line evolution and is a suitable example for orthogenesis. It started from Eocene period. The entire evolutionary sequence of horse history is recorded in North America. " Place of Origin The place of origin of horse is North America. From here, horses migrated to Europe and Asia. By the end of Pleis- tocene period, horses became extinct in the motherland (N. America). The horses now living in N. America are the de- scendants of migrants from other continents. Time of Origin The horse evolution started some 58 million years ago, m the beginning of Eocene period of Coenozoic era. The modem horse Equus originated in Pleistocene period about 2 million years ago. Evolutionary Trends The fossils of horses that lived in different periods, show that the body parts exhibited progressive changes towards a particular direction. These directional changes are called evo- lutionary trends. The evolutionary trends of horse evolution are summarized below: 1. Increase in size. 2. Increase in the length of limbs. 3. Increase in the length of the neck. 4. Increase in the length of preorbital region (face). 5. Increase in the length and size of III digit. 6. Increase in the size and complexity of brain. 7. Molarization of premolars. Olfactory bulb Hyracotherium Mesohippus Equus Fig.: Evolution of brain in horse. 8. Development of high crowns in premolars and molars. 9. Change of plantigrade gait to unguligrade gait. 10. Formation of diastema. 11. Disappearance of lateral digits. -

Exhibit Specimen List FLORIDA SUBMERGED the Cretaceous, Paleocene, and Eocene (145 to 34 Million Years Ago) PARADISE ISLAND

Exhibit Specimen List FLORIDA SUBMERGED The Cretaceous, Paleocene, and Eocene (145 to 34 million years ago) FLORIDA FORMATIONS Avon Park Formation, Dolostone from Eocene time; Citrus County, Florida; with echinoid sand dollar fossil (Periarchus lyelli); specimen from Florida Geological Survey Avon Park Formation, Limestone from Eocene time; Citrus County, Florida; with organic layers containing seagrass remains from formation in shallow marine environment; specimen from Florida Geological Survey Ocala Limestone (Upper), Limestone from Eocene time; Jackson County, Florida; with foraminifera; specimen from Florida Geological Survey Ocala Limestone (Lower), Limestone from Eocene time; Citrus County, Florida; specimens from Tanner Collection OTHER Anhydrite, Evaporite from early Cenozoic time; Unknown location, Florida; from subsurface core, showing evaporite sequence, older than Avon Park Formation; specimen from Florida Geological Survey FOSSILS Tethyan Gastropod Fossil, (Velates floridanus); In Ocala Limestone from Eocene time; Barge Canal spoil island, Levy County, Florida; specimen from Tanner Collection Echinoid Sea Biscuit Fossils, (Eupatagus antillarum); In Ocala Limestone from Eocene time; Barge Canal spoil island, Levy County, Florida; specimens from Tanner Collection Echinoid Sea Biscuit Fossils, (Eupatagus antillarum); In Ocala Limestone from Eocene time; Mouth of Withlacoochee River, Levy County, Florida; specimens from John Sacha Collection PARADISE ISLAND The Oligocene (34 to 23 million years ago) FLORIDA FORMATIONS Suwannee -

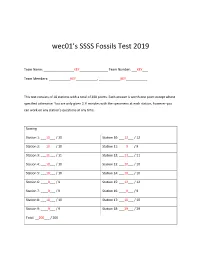

Wec01's SSSS Fossils Test 2019

wec01’s SSSS Fossils Test 2019 Team Name: _________________KEY________________ Team Number: ___KEY___ Team Members: ____________KEY____________, ____________KEY____________ This test consists of 18 stations with a total of 200 points. Each answer is worth one point except where specified otherwise. You are only given 2 ½ minutes with the specimens at each station, however you can work on any station’s questions at any time. Scoring Station 1: ___10___ / 10 Station 10: ___12___ / 12 Station 2: ___10___ / 10 Station 11: ____9___ / 9 Station 3: ___11___ / 11 Station 12: ___11___ / 11 Station 4: ___10___ / 10 Station 13: ___10___ / 10 Station 5: ___10___ / 10 Station 14: ___10___ / 10 Station 6: ____9___ / 9 Station 15: ___12___ / 12 Station 7: ____9___ / 9 Station 16: ____9___ / 9 Station 8: ___10___ / 10 Station 17: ___10___ / 10 Station 9: ____9___ / 9 Station 18: ___29___ / 29 Total: __200___ / 200 Team Number: _KEY_ Station 1: Dinosaurs (10 pt) 1. Identify the genus of specimen A Tyrannosaurus (1 pt) 2. Identify the genus of specimen B Stegosaurus (1 pt) 3. Identify the genus of specimen C Allosaurus (1 pt) 4. Which specimen(s) (A, B, or C) are A, C (1 pt) Saurischians? 5. Which two specimens (A, B, or C) lived at B, C (1 pt) the same time? 6. Identify the genus of specimen D Velociraptor (1 pt) 7. Identify the genus of specimen E Coelophysis (1 pt) 8. Which specimen (D or E) is commonly E (1 pt) found in Ghost Ranch, New Mexico? 9. Which specimen (A, B, C, D, or E) would D (1 pt) specimen F have been found on? 10. -

Wood-Eating Bivalves Daniel L

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine University of Maine Office of Research and Special Collections Sponsored Programs: Grant Reports 1-27-2006 Evolution of Endosymbiosis in (xylotrophic) Wood-Eating Bivalves Daniel L. Distel Principal Investigator; University of Maine, Orono Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/orsp_reports Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Distel, Daniel L., "Evolution of Endosymbiosis in (xylotrophic) Wood-Eating Bivalves" (2006). University of Maine Office of Research and Sponsored Programs: Grant Reports. 133. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/orsp_reports/133 This Open-Access Report is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Maine Office of Research and Sponsored Programs: Grant Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Annual Report: 0129117 Annual Report for Period:06/2004 - 06/2005 Submitted on: 01/27/2006 Principal Investigator: Distel, Daniel L. Award ID: 0129117 Organization: University of Maine Title: Evolution of Endosymbiosis in (xylotrophic) Wood-Eating Bivalves Project Participants Senior Personnel Name: Distel, Daniel Worked for more than 160 Hours: Yes Contribution to Project: Post-doc Graduate Student Name: Luyten, Yvette Worked for more than 160 Hours: Yes Contribution to Project: Graduate student participated in lab research with support from this grant. Name: Mamangkey, Gustaf Worked for more than 160 Hours: Yes Contribution to Project: Gustaf Mamangkey is a lecturer at the Tropical Marine Mollusc Programme, Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Sciences, Sam Ratulangi University,Jl. Kampus UNSRAT Bahu, Manado 95115,Indonesia. -

First Nimravid Skull from Asia Alexander Averianov1,2, Ekaterina Obraztsova3, Igor Danilov1,2, Pavel Skutschas3 & Jianhua Jin1

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN First nimravid skull from Asia Alexander Averianov1,2, Ekaterina Obraztsova3, Igor Danilov1,2, Pavel Skutschas3 & Jianhua Jin1 Maofelis cantonensis gen. and sp. nov. is described based on a complete cranium from the middle- upper Eocene Youganwo Formation of Maoming Basin, Guangdong Province, China. The new taxon Received: 08 September 2015 has characters diagnostic for Nimravidae such as a short cat-like skull, short palate, ventral surface of petrosal dorsal to that of basioccipital, serrations on the distal carina of canine, reduced anterior Accepted: 21 April 2016 premolars, and absence of posterior molars (M2-3). It is plesiomorphic nimravid taxon similar to Published: 10 May 2016 Nimravidae indet. from Quercy (France) in having the glenoid pedicle and mastoid process without ventral projections, a planar basicranium in which the lateral rim is not ventrally buttressed, and P1 present. The upper canine is less flattened than in other Nimravidae.Maofelis cantonensis gen. and sp. nov. exemplifies the earliest stage of development of sabertooth specialization characteristic of Nimravidae. This taxon, together with other middle-late Eocene nimravid records in South Asia, suggests origin and initial diversification of Nimravidae in Asia. We propose that this group dispersed to North America in the late Eocene and to Europe in the early Oligocene. The subsequent Oligocene diversification of Nimravidae took place in North America and Europe, while in Asia this group declined in the Oligocene, likely because of the earlier development of open habitats on that continent. Nimravids are cat-like hypercarnivores that developed saber-tooth morphology early in the Cenozoic and were top predators in the late Eocene – late Oligocene mammal communities of the Northern Hemisphere1–3. -

Subsurface Geology of Cenozoic Deposits, Gulf Coastal Plain, South-Central United States

REGIONAL STRATIGRAPHY AND _^ SUBSURFACE GEOLOGY OF CENOZOIC DEPOSITS, GULF COASTAL PLAIN, SOUTH-CENTRAL UNITED STATES V U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1416-G AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the current-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Survey publications re leased prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that may be listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" may no longer be available. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices listed below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books and Maps Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Tech Books and maps of the U.S. Geological Survey are available niques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications over the counter at the following U.S. Geological Survey offices, all of general interest (such as leaflets, pamphlets, booklets), single of which are authorized agents of the Superintendent of Docu copies of Earthquakes & Volcanoes, Preliminary Determination of ments. Epicenters, and some miscellaneous reports, including some of the foregoing series that have gone out of print at the Superintendent of Documents, are obtainable by mail from ANCHORAGE, Alaska-Rm. -

Gypsum in California

TN 2.4 C3 A3 i<o3 HK STATE OP CAlIFOa!lTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES msmtBmmmmmmmmmaam GYPSUM IN CALIFORNIA BULLETIN 163 1952 aou DIVl^ON OF MNES fZBar SDODSia sxh lasncisco ^"^^^^^nBM^^MMa^HBi«iaMa«NnMaMHBaaHB^HaHaa^^HHMi«nfl^HaMHiBHHHMauuHJin««aHiav^aMaHHaHHB«auKaiaMi^^M«ni^Maai^iMMWi^iM^ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DAVIS STATE OF CALIFORNIA EARL WARREN, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES WARREN T. HANNUM, Director DIVISION OF MINES FERRY BUILDING, SAN FRANCISCO 11 OLAF P. JENKINS, Chief San Francisco BULLETIN 163 September 1952 GYPSUM IN CALIFORNIA By WILLIAM E. VER PLANCK LIBRARY UNTXERollY OF CAUFC^NIA DAVIS LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL To IIlS EXCELLKNCY, TlIK IIONORAHLE EauL AVaRREN Governor of the State of California Dear Sir: I have the lionor to transmit herewitli liuUetiii 163, Gyj)- sinn in California, prepared under tlie direetion of Ohif P. Jenkins, Chief of the Division of ]\Iines. Gypsum represents one of the important non- metallic mineral commodities of California. It serves particularly two of California's most important industries, aprieulture and construction. In Bulletin 163 the author, W. p]. Xev Phinek, a member of the staff of the Division of Mines, has prepared a comprehensive treatise cover- ing all phases of the subject : history of the industry, geologic occurrence and origin of tlie minoi-al, mining, i)rocessing and marketing of the com- modity. Specific g3'psum i)roperties Avere examined and mapped. The report is profusely illustrated by maps, charts and photographs. In the preparation of the report it was necessary for the author to make field investigations, laboratory and library studies, and to determine how the mineral is used in industry as Avell as how it occurs in nature and how it is mined. -

Functional Morphology of the Vertebral Column in Remingtonocetus (Mammalia, Cetacea) and the Evolution of Aquatic Locomotion in Early Archaeocetes

Functional Morphology of the Vertebral Column in Remingtonocetus (Mammalia, Cetacea) and the Evolution of Aquatic Locomotion in Early Archaeocetes by Ryan Matthew Bebej A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ecology and Evolutionary Biology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Philip D. Gingerich, Co-Chair Professor Philip Myers, Co-Chair Professor Daniel C. Fisher Professor Paul W. Webb © Ryan Matthew Bebej 2011 To my wonderful wife Melissa, for her infinite love and support ii Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank each of my committee members. I will be forever grateful to my primary mentor, Philip D. Gingerich, for providing me the opportunity of a lifetime, studying the very organisms that sparked my interest in evolution and paleontology in the first place. His encouragement, patience, instruction, and advice have been instrumental in my development as a scholar, and his dedication to his craft has instilled in me the importance of doing careful and solid research. I am extremely grateful to Philip Myers, who graciously consented to be my co-advisor and co-chair early in my career and guided me through some of the most stressful aspects of life as a Ph.D. student (e.g., preliminary examinations). I also thank Paul W. Webb, for his novel thoughts about living in and moving through water, and Daniel C. Fisher, for his insights into functional morphology, 3D modeling, and mammalian paleobiology. My research was almost entirely predicated on cetacean fossils collected through a collaboration of the University of Michigan and the Geological Survey of Pakistan before my arrival in Ann Arbor. -

The Largest Tropical Peat Mires in Earth History

Geological Society of America Special Paper 370 2003 Desmoinesian coal beds of the Eastern Interior and surrounding basins: The largest tropical peat mires in Earth history Stephen F. Greb William M. Andrews Cortland F. Eble Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40506, USA William DiMichele Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., USA C. Blaine Cecil U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia, USA James C. Hower Center for Applied Energy Research, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA ABSTRACT The Colchester, Springfield, and Herrin Coals of the Eastern Interior Basin are some of the most extensive coal beds in North America, if not the world. The Colchester covers an area of more than 100,000 km^, the Springfield covers 73,500-81,000 km^, and the Herrin spans 73,900 km^. Each has correlatives in the Western Interior Basin, such that their entire regional extent varies from 116,000 km^to 200,000 km^. Correlatives in the Appalachian Basin may indicate an even more widespread area of Desmoinesian peatland development, although possibly sUghtly younger in age. The Colchester Coal is thin, but the Springfield and Herrin Coals reach thicknesses in excess of 3 m. High ash yields, dominance of vitrinite macerals, and abundant lycopsids suggest that these Desmoinesian coals were deposited in topogenous (groundwater fed) to solige- nous (mixed-water source) mires. The only modern mire complexes that are as wide- spread are northern-latitude raised-bog mires, but Desmoinesian -

Episodes 149 September 2009 Published by the International Union of Geological Sciences Vol.32, No.3

Contents Episodes 149 September 2009 Published by the International Union of Geological Sciences Vol.32, No.3 Editorial 150 IUGS: 2008-2009 Status Report by Alberto Riccardi Articles 152 The Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) of the Serravallian Stage (Middle Miocene) by F.J. Hilgen, H.A. Abels, S. Iaccarino, W. Krijgsman, I. Raffi, R. Sprovieri, E. Turco and W.J. Zachariasse 167 Using carbon, hydrogen and helium isotopes to unravel the origin of hydrocarbons in the Wujiaweizi area of the Songliao Basin, China by Zhijun Jin, Liuping Zhang, Yang Wang, Yongqiang Cui and Katherine Milla 177 Geoconservation of Springs in Poland by Maria Bascik, Wojciech Chelmicki and Jan Urban 186 Worldwide outlook of geology journals: Challenges in South America by Susana E. Damborenea 194 The 20th International Geological Congress, Mexico (1956) by Luis Felipe Mazadiego Martínez and Octavio Puche Riart English translation by John Stevenson Conference Reports 208 The Third and Final Workshop of IGCP-524: Continent-Island Arc Collisions: How Anomalous is the Macquarie Arc? 210 Pre-congress Meeting of the Fifth Conference of the African Association of Women in Geosciences entitled “Women and Geosciences for Peace”. 212 World Summit on Ancient Microfossils. 214 News from the Geological Society of Africa. Book Reviews 216 The Geology of India. 217 Reservoir Geomechanics. 218 Calendar Cover The Ras il Pellegrin section on Malta. The Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) of the Serravallian Stage (Miocene) is now formally defined at the boundary between the more indurated yellowish limestones of the Globigerina Limestone Formation at the base of the section and the softer greyish marls and clays of the Blue Clay Formation. -

The Phylogenetic and Palaeographic Evolution of the Miogypsinid Larger Benthic Foraminifera

The phylogenetic and palaeographic evolution of the miogypsinid larger benthic foraminifera MARCELLE K. BOUDAGHER-FADEL AND G. DAVID PRICE Department of Earth Sciences, University College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK Abstract One of the notable features of the Oligocene oceans was the appearance in Tethys of American lineages of larger benthic foraminifera, including the miogypsinids. They were reef-forming, and became very widespread and diverse, and so they play an important role in defining the Late Paleogene and Early Neogene biostratigraphy of the carbonates of the Mediterranean and the Indo-Pacific Tethyan sub-provinces. Until now, however, it has not been possible to develop an effective global view of the evolution of the miogypsinids, as the descriptions of specimens from Africa were rudimentary, and the stratigraphic ranges of genera of Tethyan forms appear to be highly dependent on palaeography. Here we present descriptions of new samples from offshore South Africa, and from outcrops in Corsica, Cyprus, Syria and Sumatra, which enable a systematic and biostratigraphic comparison of the miogypsinids from the Tethyan sub-provinces of the Mediterranean-West Africa and the Indo-Pacific, and for the first time from South Africa, which we show forms a distinct bio- province. The 116 specimens illustrated include 7 new species from the Far East, Neorotalia tethyana, Miogypsinella bornea, Miogypsina subiensis, M. niasiensis, M. regularia, M. samuelia, Miolepidocyclina banneri, 1 new species from Cyprus, Miogypsinella cyprea and 4 new species from South Africa, Miogypsina mcmillania, M. africana, M. ianmacmilliana, M. southernia. We infer that sea level, tectonic and climatic changes determined and constrained in turn the palaeogeographic distribution, evolution and eventual extinctions of the miogypsinid.