Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2009 Remarks at the Abraham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Illinois 91St General Assembly House of Representatives Transcription Debate

STATE OF ILLINOIS 91ST GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES TRANSCRIPTION DEBATE 127th Legislative Day November 15, 2000 Speaker Hartke: "The House shall come to order. The House shall come to order. We shall be led in prayer today by Lee Crawford, the Assistant Pastor of the Victory Temple Church in Springfield, Illinois. The guests in the gallery may wish to rise and join us for the invocation and remain standing for the Pledge. Pastor Crawford." Pastor Crawford: "May we lift our hearts as well as our minds. Most gracious and most kind eternal God, giver of life. Father, we ask that You judge over us as we stand humbly before You as Your sons, and as Your daughters of Your divine plan. We ask that You would stand before us as a great God, as we stand before You as a people mindful of Your great favor that You have bestowed upon us. And bless us to be mindful of Your will that You've asked us to do. So Father, I ask that Your divine presence would be upon us. That Your might would strengthen us. That Your spirit would guide us. And that Your great counsel would advise us. Father, this we kindly and humbly pray. Amen." Speaker Hartke: "We shall be led in prayer today... or the Pledge of Allegiance by Representative Andrea Moore." Moore, A. - et al: "I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all." Speaker Hartke: "Roll Call for Attendance. -

Interview with Frank Watson # ISL-A-L-2012-036 Interview # 01: August 7, 2012 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Frank Watson # ISL-A-L-2012-036 Interview # 01: August 7, 2012 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 A Note to the Reader This transcript is based on an interview recorded by the ALPL Oral History Program. Readers are reminded that the interview of record is the original video or audio file, and are encouraged to listen to portions of the original recording to get a better sense of the interviewee’s personality and state of mind. The interview has been transcribed in near- verbatim format, then edited for clarity and readability, and reviewed by the interviewee. For many interviews, the ALPL Oral History Program retains substantial files with further information about the interviewee and the interview itself. Please contact us for information about accessing these materials. DePue: Today is Tuesday, August 7, 2012. My name is Mark DePue, Director of Oral History for the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. Today I’m in Greenville, Illinois with former Senator Frank Watson. Good afternoon. Watson: Mark, good afternoon. DePue: I hope this is the first of many sessions that we have. Watson: It’s hopefully not as many as Jim Edgar had (laughs). -

Title Page & Abstract

Title Page & Abstract Restricted Interview An Interview with Julie Cellini Part of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library IHPA Legacy Oral History project Interview # HP-A-L-2015-013 Julie Cellini, the chair of the IHPA Board of Trustees and one of the main forces behind the creation of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, was interviewed on the date listed below as part of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library’s IHPA Legacy Oral History project. Interview dates & location: Date: Mar 9, Mar 11, Mar 17, Mar 26, Apr 22, May 5, Jul 13 & Oct 6, 2015 Interview Format: Digital audio Interviewer: Mark R. DePue, Director of Oral History, ALPL Transcript Transcription by: _________________________ being processed Edited by: _______________________________ Total Pages: ______ Total Time: 1:26(1) + 2:13(2) + 2:12(3) + 1:34(4) + 2:27(5) + 1:44(6) + 1:26(7) + 1:56(8) /1.43(1) + 2.22(2) + 2.2(3) + 1.57(4) + 2.45(5) + 1.73(6) + 1.43(7) + 1.93(8) = 14.96 hrs Session 1: Early years and journalistic career in Springfield Session 2: Service on the Historic Library Board and Chair of the new IHPA Session 3: Early years of IHPA, and initial planning stages for the ALPLM Session 4: Development of President Lincoln Museum exhibits Session 5: Museum exhibits, continued, planning for library and siting decisions Session 6: Funding for ALPLM and construction and staffing for ALPLM Session 7: Opening of the Library and Museum, and early management issues Session 8: Reflections on IHPA and ALPLM since 2011, and closing comments Accessioned into the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Archives on April 5, 2017. -

IDENTIFIERS Best Practices;* Illinois; Illinois State Board of Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 481 221 PS 031 563 TITLE Little Prints, 2001. PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 42p.; Produced by the Illinois State Board of Education, Early Childhood Education. AVAILABLE FROM The Center: Resources for Teaching and Learning, 1855 Mt. Prospect Road, Des Plaines, IL 60018. Tel: 847-803-3565; Fax: 847-803-3556; Web site: http://www.thecenterweb.org. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Little Prints, 2001; vl n1-3 2001 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Accreditation (Institutions); Case Studies; *Early Childhood Education; *Educational Quality; Educational Trends; Longitudinal Studies IDENTIFIERS Best Practices; *Illinois; Illinois State Board of Education; National Association Educ of Young Children; *Universal Preschool ABSTRACT Providing the early childhood (EC) community with a timely, actionable information about the Illinois State Board of Education's early learning initiative, "Little Prints" is a newsletter highlighting best practices among EC programs, representing the interests of and issues of EC professionals engaged in the education and care of children from birth to age 8, and working with other EC publications to inform the broader EC community of the links that bind individual programs into an essential continuum of EC services. This document consists of the first three issues of the newsletter, covering the year 2001. Issue 1 introduces the newsletter, highlights the work of an Alabama early childhood researcher working to create a multistate technical assistance program that would share resources across many Southern states, and describes an early childhood best practices site. Focusing on program quality, the second issue features case studies of two exemplary programs, describes the NAEYC accreditation process, highlights family resource center services in a rural county, and points out the gap between what early childhood development research says children need and what is actually offered in preschool settings. -

Senate Journal

SENATE JOURNAL STATE OF ILLINOIS NINETY-THIRD GENERAL ASSEMBLY 1ST LEGISLATIVE DAY WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 8, 2003 12:00 O'CLOCK NOON [January 8, 2003] 2 NO. 1 SENATE Daily Journal Index 1st Legislative Day Action Page(s) Presentation of Senate Resolutions No. ..................................................... 9, 10, 33 Report from Rules Committee ....................................................................... 31, 34 Bill Number Legislative Action Page(s) SR 0001 Adopted ....................................................................................................................... 31 SR 0001 Committee on Rules ...................................................................................................... 9 SR 0002 Adopted ....................................................................................................................... 32 SR 0002 Committee on Rules .................................................................................................... 10 SR 0003 Adopted ....................................................................................................................... 34 SR 0003 Committee on Rules .................................................................................................... 33 SR 0004 Adopted ....................................................................................................................... 34 SR 0004 Committee on Rules .................................................................................................... 33 SR 0005 Adopted -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 464 635 IR 058 441 AUTHOR Lamolinara, Guy, Ed. TITLE The Library of Congress Information Bulletin, 2000. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. ISSN ISSN-0041-7904 PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 480p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/. v PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Library of Congress Information Bulletin; v59 n1-12 2000 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Electronic Libraries; *Exhibits; *Library Collections; *Library Services; *National Libraries; World Wide Web IDENTIFIERS *Library of Congress ABSTRACT These 12 issues, representing one calendar year (2000) of "The Library of Congress Information Bulletin," contain information on Library of Congress new collections and program developments, lectures and readings, financial support and materials donations, budget, honors and awards, World Wide Web sites and digital collections, new publications, exhibits, and preservation. Cover stories include:(1) "The Art of Arthur Szyk: 'Artist for Freedom' Featured in Library Exhibition";(2) "The Year in Review: 1999 Marks Start of Bicentennial Celebration"; (3) "'A Whiz of a Wiz': New Library Exhibition on 'The Wizard of Oz' Opens"; (4) "The Many Faces of Thomas Jefferson: Father of the Library Subject of New Exhibition"; (5) Library of Congress bicentennial events; (6) "Thanks for the Memory: New Bob Hope Gallery Opens at Library"; (7) "Local Legacies: American Culture Captured in Bicentennial Program"; (8) "America at Work, School and Play: Web Films Document American Culture, 1894-1915"; (9) "Herblock's History Political Cartoon Exhibition Opens Oct. 17";(10) "Aaron Copland Centennial"; and (11)"Al Hirschfeld: Beyond Broadway: Exhibition of Work by Famed Graphic Artist Open." (Contains 91 references.) MES) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Lincoln in Illinois

ABRAHAM LINCOLN IN ILLINOIS A SELECTION OF DOCUMENTS FROM THE ILLINOIS STATE ARCHIVES TEACHER’S MANUAL by Illinois State Archives Staff David Joens, Director Dr. Wayne C. Temple, Deputy Director Elaine Shemoney Evans Dottie Hopkins-Rehan Timothy Mottaz John Reinhardt Lori Roberts Mark Sorensen ILLINOIS STATE ARCHIVES OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE SPRINGFIELD 2008 ABRAHAM LINCOLN IN ILLINOIS A SELECTION OF DOCUMENTS FROM THE ILLINOIS STATE ARCHIVES TEACHER’S MANUAL by Illinois State Archives Staff David Joens, Director Dr. Wayne C. Temple, Deputy Director Elaine Shemoney Evans Dottie Hopkins-Rehan Timothy Mottaz John Reinhardt Lori Roberts Mark Sorensen ILLINOIS STATE ARCHIVES OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE SPRINGFIELD 2008 Funding for the production of the Abraham Lincoln in Illinois teaching packet was awarded by the Illinois State Library (ISL), a Division of the Office of Secretary of State, using funds provided by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), under the federal Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA). Printed by the Authority of the State of Illinois PO# 09AV01500 11/08 3.7M CONTENTS Introduction ..........................................................................................................................1 Objectives ............................................................................................................................2 Use of Documents ................................................................................................................4 Historical Background -

Illinois Register Cover 2011:Layout 1

2011 ILLINOIS RULES OF GOVERNMENTAL REGISTER AGENCIES Index Department Administrative Code Division 111 E. Monroe St. Springfield, IL 62756 217-782-7017 www.cyberdriveillinois.com Printed on recycled paper PUBLISHED BY JESSE WHITE • SECRETARY OF STATE TABLE OF CONTENTS July 29, 2011 Volume 35, Issue 31 PROPOSED RULES CENTRAL MANAGEMENT SERVICES, DEPARTMENT OF State Vehicles and Garage 44 Ill. Adm. Code 5040....................................................................12592 HEALTHCARE AND FAMILY SERVICES, DEPARTMENT OF Medical Payment 89 Ill. Adm. Code 140......................................................................12600 NATURAL RESOURCES, DEPARTMENT OF Snowmobile Trail Establishment Fund Grant Program 17 Ill. Adm. Code 3020....................................................................12624 POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD Effluent Standards 35 Ill. Adm. Code 304......................................................................12634 PUBLIC HEALTH, DEPARTMENT OF Emergency Medical Services and Trauma Center Code 77 Ill. Adm. Code 515......................................................................12645 Newborn Metabolic Screening and Treatment Code 77 Ill. Adm. Code 661......................................................................12668 SECRETARY OF STATE Illinois State Library Grant Programs 23 Ill. Adm. Code 3035....................................................................12686 STATE POLICE, DEPARTMENT OF Testing of Breath, Blood and Urine for Alcohol, Other Drugs, and Intoxicating Compounds 20 Ill. Adm. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES—Wednesday, October 4, 2000

October 4, 2000 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE 20663 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—Wednesday, October 4, 2000 The House met at 10 a.m. and was come forward and lead the House in the S. Con. Res. 141. Concurrent resolution to called to order by the Speaker pro tem- Pledge of Allegiance. authorize the printing of copies of the publi- pore (Mr. SHAW). Mr. MORAN of Kansas led the Pledge cation entitled ‘‘The United States Capitol’’ as a Senate document. f of Allegiance as follows: f DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Repub- PRO TEMPORE WELCOME TO REVEREND lic for which it stands, one nation under God, LAWRENCE A. LAMBERT, JR. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. (Mr. MORAN of Kansas asked and fore the House the following commu- f nication from the Speaker: was given permission to address the MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE House for 1 minute and to revise and WASHINGTON, DC, October 4, 2000. A message from the Senate by Mr. extend his remarks.) I hereby appoint the Honorable E. CLAY Lundregan, one of its clerks, an- Mr. MORAN of Kansas. Mr. Speaker, SHAW, Jr., to act as Speaker pro tempore on nounced that the Senate has passed I am here to welcome to the House this day. without amendment bills of the House Chamber and to our Nation’s Capitol J. DENNIS HASTERT, of the following titles: one of my constituents and one of the Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

Annual Report 2001 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Lumpkin College Annual Reports Administration & Publications 2001 Annual Report 2001 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/lumpkin_annualreports Part of the Technology and Innovation Commons Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Annual Report 2001" (2001). Lumpkin College Annual Reports. 23. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/lumpkin_annualreports/23 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Administration & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lumpkin College Annual Reports by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contents . Message from the Dean 2 Special Recognitions 4 Student llonors 7 LCBAS Development Office Office of the Dean 9 LCBAS Academic Computing Martha S. Brown, Acting Dean 10 Business and Technology Institute Lisa Dallas, Assistant to the Detm for Aradnnir Computing II School of Business Pat Hill, Publirations, Srhokmhip, and flllemotionolz3 School of Family and Consumer Visits Coordinator Sciences Diane Ingle, Assistant to the Demt 30 School of Technology Patti Henderson, Offirt Systems Specialist 36 Department of Military Science Admissions/Advisors 38 Graduate Programs Kathy Bennett, Assistant 10 the Dean Mary Hennig, At/visor, Srhool of Business 41 FYZOO I Donors Betsy Miller, Advisor, School of Technology 45 Advisory Boards Rose Myers-Bradley, At/visor, School of Family & Co11stmttr Srimrts 47 Student Organizations Lea Northam, At/visor, School of Bu.sittess Renee Stroud, Admissio11s Offim; Srhool of 811siness Kay Amyx, OffKe S)'strms Assistalii Business & Technology Institute Marilyn DeRuiter, Direttor joy Rainey, 0/fire Systems Spetialist Development Office jackie Joines, Detirlopmettt Offirer F./lstml Illinois UnMrsity is till rqufll oppommity/tqual acass/af!imlfiiM nrtion tmplo)'tr rommilltd to ad1ieving a diverst ro1111111111ity. -

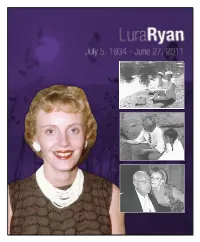

71586-Memory-Folder.Pdf

6 Lura Lynn Ryan was a passionate, caring, determined woman who dedicated her life to helping others. She purposely looked for ways to give to those less fortunate, selfl essly giving of her time and talents to enrich the lives of those around her. Lura Lynn faced many challenges in her lifetime, yet enjoyed so many triumphs. Her greatest triumph was found in her beloved family, who carry her unconditional love and selfl essness with them today. Her life was lived as a testament to her faith, family and community and serves as an inspiration to us all. Born on July 5, 1934, Lura Lynn Lowe grew up on the family farm in Aroma Park, Illinois, near Kankakee. Lura Lynn loved her small community in Aroma Park; it was the place she called home, and the place where she created many wonderful memories with family and friends. In later years, the town honored her with a street named after her. She received her education in the area schools, and it was during an English class in her freshman year at Kankakee High School that Lura Lynn met the future governor, George H. Ryan. As fate would have it, they fell in love and were married in 1956 in Kankakee. Within a year, the couple welcomed the birth of their fi rst child, daughter Nancy. She was later joined by fi ve younger siblings: Lynda, triplets - Julie, Joanne, Jeanette, and George Jr., who rounded out the Ryan household with six children. Lura Lynn exemplifi ed all that a mother should be - generous, caring and a true friend. -

Title Page & Abstract

Title Page & Abstract An Interview with Kathryn Harris Part of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library IHPA Legacy Oral History project Interview # HP-A-L-2016-039 Katheryn Harris, the former Director of Library Services at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, was interviewed on the date listed below as part of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library’s IHPA Legacy Oral History project. Interview dates & location: Dates: Aug 3, 16, 23, 31 & Sep 6, 2016 Interview Format: Digital audio Interviewer: Mark R. DePue, Director of Oral History, ALPL Transcription by: _________________________ Transcript being processed Edited by: _______________________________ Total Pages: ______ Total Time: 1:52 + 0:54 + 1:22 + 2:00 + 2:03 / 1.87 + 0.9 + 1.37 + 2.0 + 2.05 = 8.19 hrs. Session 1: Early years with IL State Historical Library, 1984-1991 Session 2: IL State Historical Library during its move to the Howlett Bldg., 1993-95 Session 3: Selection as director of Library, and planning for new Library & Museum Session 4: Opening of new Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and the Museum Session 5: Staff challenges and changes in the years since opening of ALPLM Accessioned into the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Archives on January 3, 2017. The interviews are archived at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield, Illinois. © 2016 Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Abstract Kathryn Harris, IHPA Legacy, HP-A-L-2016-039 Biographical Information Overview of Interview: Kathryn Harris was born on December 5th, 1947 in Carbondale, Illinois. Her early life and family history is preserved in an interview in the ALPL Oral History Family Memories project.