Baseball' Noble Experiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

Major League Baseball's I-Team

Major League Baseball’s I-Team The I-Team is composed of players whose names contain enough unique letters to spell the team(s) for which they played. To select the team, the all-time roster for each franchise was compared to both its current name as well as the one in use when each player was a member of the team. For example, a member of the Dodgers franchise would be compared to both that moniker (regardless of the years when they played) as well as alternate names, such as the Robins, Superbas, Bridegrooms, etc., if they played during seasons when those other identities were used. However, if a franchise relocated and changed its name, the rosters would only be compared to the team name used when each respective player was a member. Using another illustration, those who played for the Senators from 1901 to 1960 were not compared to the Twins name, and vice versa. Finally, the most common name for each player was used (as determined by baseball- reference.com’s database). For example, Whitey Ford was used, not Edward Ford. Franchise Team Name Players Angels Angels Al Spangler Angels Angels Andres Galarraga Angels Angels Claudell Washington Angels Angels Daniel Stange Angels Angels Jason Bulger Angels Angels Jason Grimsley Angels Angels Jose Gonzalez Angels Angels Larry Gonzales Angels Angels Len Gabrielson Angels Angels Paul Swingle Angels Angels Rene Gonzales Angels Angels Ryan Langerhans Angels Angels Wilson Delgado Astros Astros Brian Esposito Astros Astros Gus Triandos Astros Astros Jason Castro Astros Astros Ramon de los Santos -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

The Newsletter of WASHINGTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY Newsletter #3 March 2016

The Newsletter of WASHINGTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY Newsletter #3 March 2016 Hodge School Reunion WHS Ramp Project Completed An enthusiastic group attended the Hodge School Reunion sponsored by WHS last year. Guests Shelley Eaton nods her arrived at the tiny school building with boisterous approval of the ramp at WHS greetings and hugs and soon filled the space with Open House lively conversations. Everyone enjoyed seeing During the summer familiar items and reviewing the signage added by of 2015, the the museum. The Hodge students contact list was put Historical Society together by WHS members, with help from Henry built a ramp to and Dorothy Sainio and Ford Powell and about make Razorville thirty-five resulted in contacts. Hodge School was Hall, accessible. built in Washington in 1864 and served the The project was funded with a $2000 grant from the community for one-hundred years, closing in 1954. Saxifrage Opportunity Grants Fund of the Maine The structure was donated to Matthews Museum by Community Foundation at the recommendation of Harlan and Evelyn Sidelinger and moved to Union the Knox County Community advisors. The ramp Fairgrounds in 1978 to protect it from deterioration. was designed and constructed by All Aspects Harlan, his father Burtelle, and all his children Builders owner Duane Vigue and meets all ADA attended Hodge school. criteria. Volunteer labor and materials were used as part of the in-kind requirement which included tree and brush removal and ground work. Many thanks Merton Moore for donating the fill and gravel, to Kendall and Michelle Jones, Jud Butterman, and Frank Campbell for their labor, and Don Grinnell for use of his tractor in site preparation. -

Ou Know What Iremember About Seattle? Every Time Igot up to Bat When It's Aclear Day, I'd See Mount Rainier

2 Rain Check: Baseball in the Pacific Northwest Front cover: Tony Conigliaro 'The great things that took place waits in the on deck circle as on all those green fields, through Carl Yastrzemski swings at a Gene Brabender pitch all those long-ago summers' during an afternoon Seattle magine spending a summer's day in brand-new . Pilots/Boston Sick's Stadium in 1938 watching Fred Hutchinson Red Sox game on pitch for the Rainiers, or seeing Stan Coveleski July 14, 1969, at throw spitballs at Vaughn Street Park in 1915, or Sick's Stadium. sitting in Cheney Stadium in 1960 while the young Juan Marichal kicked his leg to the heavens. Back cover: Posing in 1913 at In this book, you will revisit all of the classic ballparks, Athletic Park in see the great heroes return to the field and meet the men During aJune 19, 1949, game at Sick's Stadium, Seattle Vancouver, B.C., who organized and ran these teams - John Barnes, W.H. Rainiers infielder Tony York barely misses beating the are All Stars for Lucas, Dan Dugdale, W.W. and W.H. McCredie, Bob throw to San Francisco Seals first baseman Mickey Rocco. the Northwestern Brown and Emil Sick. And you will meet veterans such as League such as . Eddie Basinski and Edo Vanni, still telling stories 60 years (back row, first, after they lived them. wrote many of the photo captions. Ken Eskenazi also lent invaluable design expertise for the cover. second, third, The major leagues arrived in Seattle briefly in 1969, and sixth and eighth more permanently in 1977, but organized baseball has been Finally, I thank the writers whose words grace these from l~ft) William played in the area for more than a century. -

The Philadelphia Stars, 1933-1953

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 2002 A faded memory : The hiP ladelphia Stars, 1933-1953 Courtney Michelle Smith Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Recommended Citation Smith, Courtney Michelle, "A faded memory : The hiP ladelphia Stars, 1933-1953" (2002). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 743. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Smith, Courtney .. Michelle A Faded Memory: The Philadelphia . Stars, 1933-1953 June 2002 A Faded Memory: The Philadelphia Stars, 1933-1953 by Courtney Michelle Smith A Thesis Presentedto the Graduate and Research Committee ofLehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master ofArts m the History Department Lehigh University May 2002 Table of Contents Chapter-----' Abstract, '.. 1 Introduction 3 1. Hilldale and the Early Years, 1933-1934 7 2. Decline, 1935-1941 28 3. War, 1942-1945 46 4. Twilight Time, 1946-1953 63 Conclusion 77 Bibliography ........................................... .. 82 Vita ' 84 iii Abstract In 1933, "Ed Bolden and Ed Gottlieb organized the Philadelphia Stars, a black professional baseball team that operated as part ofthe Negro National League from 1934 until 1948. For their first two seasons, the Stars amassed a loyal following through .J. regular advertisements in the Philadelphia Tribune and represented one of the Northeast's best black professional teams. Beginning in 1935, however, the Stars endured a series of losing seasons and reflected the struggles ofblack teams to compete in a depressed economic atmosphere. -

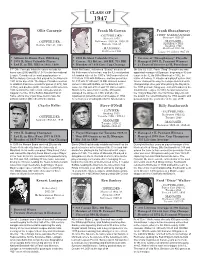

Class of 1947

CLASS OF 1947 Ollie Carnegie Frank McGowan Frank Shaughnessy - OUTFIELDER - - FIRST BASEMAN/MGR - Newark 1921 Syracuse 1921-25 - OUTFIELDER - Baltimore 1930-34, 1938-39 - MANAGER - Buffalo 1934-37 Providence 1925 Buffalo 1931-41, 1945 Reading 1926 - MANAGER - Montreal 1934-36 Baltimore 1933 League President 1937-60 * Alltime IL Home Run, RBI King * 1936 IL Most Valuable Player * Creator of “Shaughnessy” Playoffs * 1938 IL Most Valuable Player * Career .312 Hitter, 140 HR, 718 RBI * Managed 1935 IL Pennant Winners * Led IL in HR, RBI in 1938, 1939 * Member of 1936 Gov. Cup Champs * 24 Years of Service as IL President 5’7” Ollie Carnegie holds the career records for Frank McGowan, nicknamed “Beauty” because of On July 30, 1921, Frank “Shag” Shaughnessy was home runs (258) and RBI (1,044) in the International his thick mane of silver hair, was the IL’s most potent appointed manager of Syracuse, beginning a 40-year League. Considered the most popular player in left-handed hitter of the 1930’s. McGowan collected tenure in the IL. As GM of Montreal in 1932, the Buffalo history, Carnegie first played for the Bisons in 222 hits in 1930 with Baltimore, and two years later native of Ambroy, IL introduced a playoff system that 1931 at the age of 32. The Hayes, PA native went on hit .317 with 37 HR and 135 RBI. His best season forever changed the way the League determined its to establish franchise records for games (1,273), hits came in 1936 with Buffalo, as the Branford, CT championship. One year after piloting the Royals to (1,362), and doubles (249). -

Branding Through the Seven Statues of Jackie Robinson

This is a repository copy of Ballplayer or barrier breaker? Branding through the seven statues of Jackie Robinson. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/86565/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Stride, C. orcid.org/0000-0001-9960-2869, Thomas, F. and Smith, M.M. (2014) Ballplayer or barrier breaker? Branding through the seven statues of Jackie Robinson. International Journal of the History of Sport, 31 (17). pp. 2164-2196. ISSN 0952-3367 https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2014.923840 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Ballplayer or Barrier Breaker? Branding Through the Seven Statues of Jackie Robinson Abstract Jackie Robinson is the baseball player most frequently depicted by a public statue within the US, a ubiquity explained by his unique position as barrier-breaker of the Major League colour bar. -

Concord Review

THE CONCORD REVIEW I am simply one who loves the past and is diligent in investigating it. K’ung-fu-tzu (551-479 BC) The Analects Proclamation of 1763 Samuel G. Feder Ramaz School, New York, New York Kang Youwei Jessica Li Kent Place School, Summit, New Jersey Lincoln’s Reading George C. Holderness Belmont Hill School, Belmont, Massachusetts Segregation in Berkeley Maya Tulip Lorey College Preparatory School, Oakland, California Quebec Separatism Iris Robbins-Larrivee King George Secondary School, Vancouver, British Columbia Jackie Robinson Peter Baugh Clayton High School, Clayton, Missouri Mechanical Clocks Mehitabel Glenhaber Commonwealth High School, Boston, Massachusetts Anti-German Sentiment Hendrick Townley Rye Country Day School, Rye, New York Science and Judaism Jonathan Slifkin Horace Mann School, Bronx, New York Barbie Doll Brittany Arnett Paul D. Schreiber High School, Port Washington, New York German Navy in WWI Renhua Yuan South China Normal University High School, Guangzhou A Quarterly Review of Essays by Students of History Volume 24, Number Two $20.00 Winter 2013 Editor and Publisher Will Fitzhugh E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: http://www.tcr.org/blog NEWSLETTER: Click here to register for email updates. The Winter 2013 issue of The Concord Review is Volume Twenty-Four, Number Two This is the eBook edition. Partial funding was provided by: Subscribers, and the Consortium for Varsity Academics® ©2013, by The Concord Review, Inc., 730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24, Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776, USA. All rights reserved. This issue was typeset on an iMac, using Adobe InDesign, and fonts from Adobe. EDITORIAL OFFICES: The Concord Review, 730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24, Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776 USA [1-800-331-5007] The Concord Review (ISSN #0895-0539), founded in 1987, is published quarterly by The Concord Review, Inc., a non-profit, tax-exempt, 501(c)(3) Massachusetts corporation. -

National Pastime

""a The Theatre Academy of Los Angeles City College in association with The Jackie Robinson Foundation presents Production Number 844,78th Season, March 16, 17 & 21- 24,2007 NATIONAL PASTIME Written by Brian Hametiaux Directed by Louie Piday Scenic Design Lighting Design Kevin Morrissey Jim Moody Costume Design Sound Design Tanya Bishop* Kevin Morrissey CAST Jackie Robinson......................................... Egbert Bernard Mallie Robinson ...................................Constance Strickland Rachel Islum ................................................Amber Harris Wendell Smith........................................ John Christopher Branch Rickey.................................................. A1 Rossi** Jane Rickey................................................. Louie Piday** Walter "Red" Barber.. .............................. James Hurley* * Lylah Barber...................................... Sheena Lorene Duff Clyde Sukeforth..................................... Michael Hausner Bus Driver............................................. Charles De Groot Officer.. ........................................................... Jerid James George "Mule" Suttles.................................. Martin Head Leroy "SatcheOl" Paige ........................... William Daniels Harold "Pee Wee" Reese ................................ Jerid James Fred "Dixie" Walker............................... Michael Hausner Messenger............................................. Charles De Groot *Student Designer ** Guest Artists There will he iinefifteen -

Autumn 2013 the Line-O-Type MAINE MASON by George P

The Maine Mason Autumn 2013 The line-o-type MAINE MASON by George P. Pulkkinen Like a cauldron of thick, delicious stew cooking over a bed of glimmering maple embers, THE MAINE MASON is an official publication of the Grand Lodge of Maine, Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. The Masonry in Maine is bubbling. material printed herein does not necesarily represent opinions Activities, like that stew, are feeding Masons of the Grand Lodge of Maine. with new information and skills that will nurture At the 162nd Annual Communication of the Grand Lodge of and strengthen brethren and lodges throughout Maine in 1981, legislation was adopted to provide THE MAINE the Pine Tree State. MASON to every member of the constituted lodges within this The enthusiam men are showing after attend- Grand Lodge without additional charge. ing the Leadership and Mentoring workshops Members of lodges within other Grand Jurisdictions within the United States are invited to subscribe to THE MAINE MASON at will be demonstrated, in very positive ways, in $3.00 per year. Cost for Masons outside the United States is their lodge rooms, in their personal lives and $5.00 Please send check payable to THE MAINE MASON with throughout their communities. And the Rookie complete mailing address to the Grand Secretary at the address Program provides a fast track for new members printed below. to realize full value from their Masonic member- ADDRESS CHANGES: Subscribers are advised to notify the ships. Grand Secretary’s office of any address change. Throughout this issue you’ll find articles Editor describing these programs and providing infor- George P. -

The Jackie Robinson Story (United Artists Pressbook, 1950)

AN EAGLE LION FILMS PRESS BOOK TREMENDOUS NEWSPAPER, MAGAZINE, PROMOTION CAMPAIGNS ...ALL GUARANTEED TO HELP YOU LOCALLY! Ckie Highest ft Terrific Treat y\ Wants Tou to Wear m , Jj# mOSWRTS.SmTSHWS^ ROeoeR 'MM ^ ^«rHAND\S\NG ? At AND LOCAL Robinson Stor set to moke _ pictores ever mo' nerchandised *" ^.°ke ChesterficlT ^mucii Milder JACKIE ROBINSON “The Pride of Brooklyn” as HIMSELF 1. Your "big stunt" on "The Jackie Robin¬ son Story" might be a "Jackie Robinson in Day" which you could set up in co-op- operation with a local baseball team. Idea of "Day" is that part of proceeds from both game and opening showing of the picture can be donated to local youth organizations; a type of work Jackie is most interested in. 2. In planting publicity material remember that the picture has many angles which are suitable for sports and general pages THE |n as well as movie pages. (See Pages 18- 22 in this Press Book). 3. Special attention should be given to all spots in town where the sporting fra¬ ternity congregates. These should be well covered with window cards, throw¬ aways, etc. 4. Follow through on the merchandising promotions on pages 6-9 of this Press i JACKIE , Book in order to promote quantities of material which can be used for give¬ aways and contest prizes. 5. Your front and lobby on "The Jackie Robinson Story" should, of course, re¬ flect the predominantly baseball motif of the picture. Main art of Jackie Robinson can be mounted above the marquee with plenty of baseball action stills under mar¬ quee.