1. the Kyrgyz Republic Remains Dependent on Agriculture. The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kyrgyzstan Extended Migration Profile 2010-2015

NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE KYRGYZ REPUBLIC Kyrgyzstan Extended Migration Profile 2010-2015 Kazahkstan Talas Bishkek Chuy oblast Balykchy Talas oblast Karakol Issyk-Kul oblast Jalalabad oblast Naryn oblast Jalalabad Uzbekistan Naryn Osh Batken Osh oblast Batken oblast China Tadjikistan УДК 325 ББК 60.7 К 97 National Institute for Strategic Studies of the Kyrgyz Republic International Organization for Migration Editorial team Chief Editor: T. I. Sultanov Authors: G. K. Ibraeva, M. K. Ablezova Managing Editors: S. V. Radchenko, J. R. Irsakova, E. A. Omurkulova-Ozerska, M. Manke, O. S. Chudinovskikh, A. V. Danshina, J. S. Beketaeva, A.T. Bisembina Interagency Working Group: E. A. Omurkulova-Ozerska - National Institute for Strategic Studies of the Kyrgyz Republic J. R. Irsakova - National Institute for Strategic Studies of the Kyrgyz Republic T. S. Taipova - The National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic G. J. Jaylobaeva - The National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic A. Z Mambetov - Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Kyrgyz Republic Mirlan Sarlykbek uulu - State Border Service of the Kyrgyz Republic B. O. Arzykulova - Ministry of Health of the Kyrgyz Republic J. N. Omurova - Ministry of Economy of the Kyrgyz Republic S. A. Korchueva - Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kyrgyz Republic A. K. Minbaev - State Registration Service under the Government of the Kyrgyz Republic U. Shamshiev - State Migration Service of the Kyrgyz Republic B. S. Aydakeeva - State Migration Service of the Kyrgyz Republic Design and layout: М.S. Blinova К 97 Kyrgyzstan – extended migration profile – B.: 2016 K 0703000000-16 УДК 325 ББК 60.7 ISBN 978-9967-11-550-7 KYRGYZSTAN EXTENDED MIGRATION PROFILE 2010-2015 This Extended Migration Profile was prepared in the framework of the Global Programme Mainstreaming Migration into Development Strategies implemented by the International Organization for Migration and the United Nations Development Programme with the financial support of the Government of Switzerland. -

List of Participants

E/ESCAP/FAMT(2)/INF/2 Distr.: For participants only 14 November 2013 English only Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Forum of Asian Ministers of Transport Second session Bangkok, 4-8 November 2013 List of participants Members Armenia Representative H.E. Mr. Hrant Beglaryan, First Deputy Minister, Ministry of Transport and Communication, Yerevan Deputy representative Mr. Artur Sargsyan, Acting Head, Foreign Relations and Programmes Department, Ministry Transport and Communication, Yerevan Azerbaijan Representative Mr. Fikrat Babayev, Head, International Relations Department, Ministry of Transport, Baku Deputy representative Mr. Farid Valiyev, Senior Officer, International Relations Department, Ministry of Transport, Baku Bangladesh Representative H.E. Mr. Kazi Imtiaz Hossain, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary and Permanent Representative to ESCAP, Embassy of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Bangkok Deputy representative Mr. Abul Kashem Md. Badrul Majid, Joint Secretary, Roads Division, Ministry of Communication, Dhaka DMR A2013-000436 TP191113 FAMT2_INF2E E/ESCAP/FAMT(2)/INF/2 Alternates Mr. Md. Abdullah Al Masud Chowdhury, Economic Counsellor and Alternate Permanent Representative to ESCAP, Embassy of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Bangkok Mr. Md. Mozammel Hoque, General Manager (Projects), Bangladesh Railways, Ministry of Railways, Dhaka Bhutan Representatives H.E. Mr. D.N. Dungyel, Minister, Ministry of Information and Communications, Thimphu H.E. Mr. Kesang Wangdi, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary and Permanent Representative to ESCAP, Royal Bhutanese Embassy, Bangkok Alternates Mr. Bhimlal Suberi, Chief Planning Officer, Policy and Planning Division, Ministry of Information and Communication, Thimphu Mr. Sonam Phuntsho, Counsellor (Political), Royal Bhutanese Embassy, Bangkok Cambodia Representative H.E. Mr. Tauch Chankosol, Secretary of State, Ministry of Public Works and Transport, Phnom Penh Deputy representative Mr. -

Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC DEVELOPMENT OF ASIA - EUROPE RAIL CONTAINER TRANSPORT THROUGH BLOCK-TRAINS NORTHERN CORRIDOR OF THE TRANS-ASIAN RAILWAY UNITED NATIONS New York, 1999 CONTENTS Page Chapter 1: Introduction ………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter 2: Routes of the TAR Northern Corridor ……………………………………... 7 Chapter 3: Assessment of Container Traffic Volumes ………………………………… 10 3.1. Assessment of Container Traffic Volumes …………………………. 10 3.2. Distribution of Container Traffic among TAR-NC Routes ………… 16 Chapter 4: Freight Forwarders’ Choice of « Best Route » …………………………….. 20 4.1. Definitions …………………………………………………………... 20 4.2. Business Environment of Container Traffic ………………………… 21 4.3. Selecting a Transport Mode / Choosing a Route ……………………. 25 4.3.1. Cost / Tariffs ……………………………………………….. 26 4.3.2. Transit Times ………………………………………………. 30 4.3.3. Level of Services …………………………………………... 34 Chapter 5: Proposed Guidelines for the Implementation of Actual Demonstration Runs of Container Block-Trains …………………………………………… 43 5.1. Compatibility of train assembly …………………………………….. 44 5.1.1. Number of wagons – Train length …………………………. 44 5.1.2. Wagon capacity …………………………………………….. 45 5.1.3. Maximum gross weight of trains …………………………... 46 5.2. The break-of-gauge issue …………………………………………… 47 5.3. Container handling capacity in ports and terminals ………………… 49 5.4. Composition of a container block-train ……………………………... 49 5.5. Train schedule ………………………………………………………. 50 5.5.1. Main-line operations ………………………………………. 50 5.5.2. Yard operations …………………………………………… 51 5.6. Border-crossing issues ……………………………………………… 54 5.7. Customs and border formalities …………………………………….. 56 5.8. Working Groups for operationalisation and monitoring of TAR-NC services ……………………………………………………………… 57 Chapter 6: Conclusion ………………………………………………………………..... 60 ANNEXES ………………………………………………………………………………… 63 Annex 1: Railway tariff policy for international freight transit traffic between North- East Asia and Europe …………………………………………..………….. -

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/288 1 October 2013

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/288 1 October 2013 (13-5230) Page: 1/103 Trade Policy Review Body TRADE POLICY REVIEW REPORT BY THE SECRETARIAT KYRGYZ REPUBLIC This report, prepared for the second Trade Policy Review of the Kyrgyz Republic, has been drawn up by the WTO Secretariat on its own responsibility. The Secretariat has, as required by the Agreement establishing the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (Annex 3 of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization), sought clarification from the Kyrgyz Republic on its trade policies and practices. Any technical questions arising from this report may be addressed to Ms. Denby Probst (022 739 5847) and Mr. Rosen Marinov (022 739 6391). Document WT/TPR/G/288 contains the policy statement submitted by the Kyrgyz Republic. Note: This report is subject to restricted circulation and press embargo until the end of the first session of the meeting of the Trade Policy Review Body on the Kyrgyz Republic. This report was drafted in English. WT/TPR/S/288 • Kyrgyz Republic - 2 - CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 8 1 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT ......................................................................................... 10 1.1 Main Features ........................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Recent Economic Developments .................................................................................. 11 1.3 Trade and Investment -

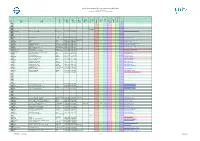

List of Numeric Codes for Railway Companies (RICS Code) Contact : [email protected] Reference : Code Short

List of numeric codes for railway companies (RICS Code) contact : [email protected] reference : http://www.uic.org/rics code short name full name country request date allocation date modified date of begin validity of end validity recent Freight Passenger Infra- structure Holding Integrated Other url 0006 StL Holland Stena Line Holland BV NL 01/07/2004 01/07/2004 x http://www.stenaline.nl/ferry/ 0010 VR VR-Yhtymä Oy FI 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.vr.fi/ 0012 TRFSA Transfesa ES 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 04/10/2016 x http://www.transfesa.com/ 0013 OSJD OSJD PL 12/07/2000 12/07/2000 x http://osjd.org/ 0014 CWL Compagnie des Wagons-Lits FR 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.cwl-services.com/ 0015 RMF Rail Manche Finance GB 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.rmf.co.uk/ 0016 RD RAILDATA CH 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.raildata.coop/ 0017 ENS European Night Services Ltd GB 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x 0018 THI Factory THI Factory SA BE 06/05/2005 06/05/2005 01/12/2014 x http://www.thalys.com/ 0019 Eurostar I Eurostar International Limited GB 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.eurostar.com/ 0020 OAO RZD Joint Stock Company 'Russian Railways' RU 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://rzd.ru/ 0021 BC Belarusian Railways BY 11/09/2003 24/11/2004 x http://www.rw.by/ 0022 UZ Ukrainski Zaliznytsi UA 15/01/2004 15/01/2004 x http://uz.gov.ua/ 0023 CFM Calea Ferată din Moldova MD 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://railway.md/ 0024 LG AB 'Lietuvos geležinkeliai' LT 28/09/2004 24/11/2004 x http://www.litrail.lt/ 0025 LDZ Latvijas dzelzceļš LV 19/10/2004 24/11/2004 x http://www.ldz.lv/ 0026 EVR Aktsiaselts Eesti Raudtee EE 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.evr.ee/ 0027 KTZ Kazakhstan Temir Zholy KZ 17/05/2004 17/05/2004 x http://www.railway.ge/ 0028 GR Sakartvelos Rkinigza GE 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://railway.ge/ 0029 UTI Uzbekistan Temir Yullari UZ 17/05/2004 17/05/2004 x http://www.uzrailway.uz/ 0030 ZC Railways of D.P.R.K. -

Euro-Asian Transport Linkages Development

Informal document No. 1 Distr.: General 20 January 2017 English only Economic Commission for Europe Inland Transport Committee Working Party on Transport Trends and Economics Group of Experts on Euro-Asian Transport Links Fifteenth session Yerevan, 31 January and 1 February 2017 Item 2 of the provisional agenda Identification of cargo flows on the Euro-Asian transport links Draft report of the phase III of the Euro-Asian Transport Links project Prepared by the "Scientific and Research Institute of Motor Transport" (NIIAT) Introduction 1. This document contains the draft final report of the phase III of the Euro-Asian Transport Links (EATL) project. It presents the results of the project’s phase III whose aim was to identify measures to make the overland EATL operational. 2. In particular, the report offers an overview and analysis of the existing situation in transport and trade along EATL routes, it reviews existing studies, programmes and initiatives on the development of EATL in the period 2013-2016, it identifies main transportation and trade obstacles in transport, trade, border-crossing, customs and transit along the EATL routes, and it formulates recommendations to overcome the identified obstacles as well as to further develop the trade across the EATL area. 3. This document is submitted to the fifteenth session of the Group of Experts on EATL for discussion and review. Informal document No. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EURO-ASIAN TRADE ROUTES AND FREIGHT FLOWS I.1. Economics and trade current situation in EATL Region I.1.1. General overview: world trade and economics I.1.2. -

List of Numeric Codes for Railway Companies

List of numeric codes for railway companies (RICS Code) contact : [email protected] reference : http://www.uic.org/spip.php?article311 code short name full name country request date allocation date modified date beginof validity of end validity recent Freight Passenger Infra- structure Holding Integrated Other url 0001 0002 0003 0004 0005 01/02/2011 0006 StL Holland Stena Line Holland BV Netherlands 01/07/2004 01/07/2004 x http://www.stenaline.nl/ferry/ 0007 0008 0009 0010 VR VR-Yhtymä Oy Finland 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.vr.fi/fi/ 0011 0012 TF Transfesa Spain 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 10/09/2013 x http://www.transfesa.com/ 0013 OSJD OSJD Poland 12/07/2000 12/07/2000 x http://osjd.org/ 0014 CWL Compagnie des Wagons-Lits France 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.cwl-services.com/ 0015 RMF Rail Manche Finance United Kingdom 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.rmf.co.uk/ 0016 RD RAILDATA Switzerland 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.raildata.coop/ 0017 ENS European Night Services Ltd United Kingdom 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x 0018 THI Factory THI Factory SA Belgium 06/05/2005 06/05/2005 01/12/2014 x http://www.thalys.com/ 0019 Eurostar I Eurostar International Limited United Kingdom 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.eurostar.com/ 0020 OAO RZD Joint Stock Company 'Russian Railways' Russia 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://rzd.ru/ 0021 BC Belarusian Railways Belarus 11/09/2003 24/11/2004 x http://www.rw.by/ 0022 UZ Ukrainski Zaliznytsi Ukraine 15/01/2004 15/01/2004 x http://uz.gov.ua/ 0023 CFM Calea Ferată din Moldova Moldova 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 -

The Kyrgyz Republic: Trade Facilitation and Logistics Development Strategy Report

The Kyrgyz Republic: Trade Facilitation and Logistics Development Strategy Report The Asian Development Bank has been supporting efforts to reduce poverty and improve livelihoods in the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) countries. A major focus of these efforts is improving the transport and trade sectors to spur economic growth and promote social and political cohesion within the region. Improving the efficiency of the CAREC transport corridors will allow these landlocked countries to take full advantage of being transit countries between the surging and dynamic economies of the East and the West. This report, one of a series of nine reports, highlights the substantial challenges that The Kyrgyz Republic needs to overcome and recommends measures to make its transport and The Kyrgyz Republic trade sectors more efficient and cost-competitive. Trade Facilitation and Logistics Development About the Asian Development Bank Strategy Report ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries substantially reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.8 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 903 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. Council GENERAL TRANS/SC.2/1999/3/Add.1 15 July 1999 Original: ENGLISH ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE INLAND TRANSPORT COMMITTEE Working Party on Rail Transport (Fifty-third session, 6-8 October 1999, agenda item 6) PRODUCTIVITY IN RAIL TRANSPORT Transmitted by the Organisation for Cooperation Between Railways (OSZhD) Note: At its fifty-second session, the Working Party asked the representative of the UIC to provide data from its member railways, and the representative of OSZhD to provide information from its member states that were not UIC members, on the following criteria (for 1997): (a) Labour productivity: (distinguishing between high-speed and conventional rail transport) employees/km of network in use Please note that the distribution of documentation for the Working Party on Rail Transport (SC.2) is no longer "restricted". Accordingly, the secretariat has adopted a new numbering system whereby all working documents other than Reports and Agendas will be numbered as follows: TRANS/SC.2/year/serial number. Reports, Agendas, resolutions and major publications will retain their previous numbering system (i.e. TRANS/SC.2/189). GE.99- TRANS/SC.2/1999/3/Add.1 page 2 net ton-km + passenger-km employee (b) Productivity of freight transport: per km: gross ton-km/km of network net ton-km/km of network per employee: gross ton-km/employee net ton-km/employee (c) Productivity of passenger transport: (distinguishing between high-speed and conventional rail transport) per km: passenger-km/km of network -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. Council GENERAL TRANS/SC.2/1999/3/Add.1 15 July 1999 Original: ENGLISH ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE INLAND TRANSPORT COMMITTEE Working Party on Rail Transport (Fifty-third session, 6-8 October 1999, agenda item 6) PRODUCTIVITY IN RAIL TRANSPORT Transmitted by the Organisation for Cooperation Between Railways (OSZhD) Note: At its fifty-second session, the Working Party asked the representative of the UIC to provide data from its member railways, and the representative of OSZhD to provide information from its member states that were not UIC members, on the following criteria (for 1997): (a) Labour productivity: (distinguishing between high-speed and conventional rail transport) employees/km of network in use Please note that the distribution of documentation for the Working Party on Rail Transport (SC.2) is no longer "restricted". Accordingly, the secretariat has adopted a new numbering system whereby all working documents other than Reports and Agendas will be numbered as follows: TRANS/SC.2/year/serial number. Reports, Agendas, resolutions and major publications will retain their previous numbering system (i.e. TRANS/SC.2/189). GE.99-22498 TRANS/SC.2/1999/3/Add.1 page 2 net ton-km + passenger-km employee (b) Productivity of freight transport: per km: gross ton-km/km of network net ton-km/km of network per employee: gross ton-km/employee net ton-km/employee (c) Productivity of passenger transport: (distinguishing between high-speed and conventional rail transport) per km: passenger-km/km of -

Logistics and Transport Competitiveness in Kyrgyzstan

UNEC E Logistics and Transport Competitiveness in Kyrgyzstan Improving the competitiveness of Kyrgyzstan as a key transport transit country at the crossroads of Europe and Asia could enable the country to unlock signicant untapped benets of growing cargo ows between the two continents. This study identies the transport infrastructure and services available in Kyrgyzstan, reviews the country’s recent and future transport investments, and sets out recommendations to ensure its transport network is ready to harness the growth in inland transport from rising key trade ows, particularly in the context of the Belt and Road Initiative, within which Kyrgyzstan’s strategic geographical position will be key to regional development. Kyrgyzstan To further capitalize on Kyrgyzstan’s pivotal role in Euro-Asian transport, this study also Logistics and Transport Competitiveness in Kyrgyzstan presents the benets of adhering to and implementing the full spectrum of UN Transport in Conventions and Legal Instruments administered by UNECE, and through its participation in UNECE initiatives such as the Euro-Asian Transport Links project. The study also highlights strengthening the full implementation of legislation as one of the most important conditions for the development of the transport infrastructure of Kyrgyzstan and the broader region. Logistics and Transport Competitiveness Information Service United Nations Economic Commission for Europe UNIT Palais des Nations CH - 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland E Telephone: +41(0)22 917 12 34 ISBN 978-92-1-117206-5 D E-mail: [email protected] N A Website: www.unece.org TION S Layout at United Nations, Geneva – (E) - November 2019 - 185 - ECE/TRANS/287 UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE LOGISTICS AND TRANSPORT COMPETITIVENESS IN KYRGYZSTAN UNITED NATIONS Geneva, 2020 © 2020 United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. Council GENERAL TRANS/SC.2/2000/3 1 September 2000 Original: ENGLISH ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE INLAND TRANSPORT COMMITTEE Working Party on Rail Transport (Fifty-fourth session, 3-5 October 2000, agenda item 6) PRODUCTIVITY IN RAIL TRANSPORT Transmitted by the Organization for Co-operation between Railways (OSZhD) At its fifty-third session, the Working Party asked the representatives of the UIC and the Organization for Co-operation between Railways (OSZhD) to provide 1998 data for its next session, following the new format used in document TRANS/SC.2/1999/3: (a) Labour productivity: employees/km of network in use (b) Productivity of freight transport: per km: net ton-km/km of network per employee: net ton-km/employee (c) Productivity of passenger transport: per km: passenger-km/km of network per employee: passenger-km/employee (d) Productivity of traffic: per km: net ton-km + passenger-km/km of network per employee: net ton-km + passenger-km/employee (f) Productivity of wagons: net ton-km/wagon GE.00- TRANS/SC.2/2000/3 page 2 (g) Productivity of lines: (where necessary only on railway lines to be determined) passenger train-km + freight train-km /km of network The Working Party may wish to consider the reply received from OSZhD, which is reproduced below. The information refers to years 1996 and 1998, as no statistics are available for the earlier years, when figures were aggregated for all railways in the Soviet Union. OSZhD has no data on the productivity of individual railway lines or the energy consumption of railways, nor does it have any information on high-speed transport.