Calendar No. 250

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book Born to Kill : the Rise and Fall of Americas Bloodiest

BORN TO KILL : THE RISE AND FALL OF AMERICAS BLOODIEST ASIAN GANG PDF, EPUB, EBOOK T J English | 310 pages | 09 Jun 2009 | William Morrow & Company | 9780061782381 | English | New York, NY, United States Born to Kill : The Rise and Fall of Americas Bloodiest Asian Gang PDF Book My library Help Advanced Book Search. Upping the ante on depravity, their specialty was execution by dismemberment. English The Westies, follows the life and criminal career of Tinh Ngo, a No trivia or quizzes yet. True crime has been enjoying something A must for anyone interested in the emerging multiethnic face of organized crime in the United States. June 16, This was a really great read considering it covers a part of Vietnamese American culture that I had never encountered or even heard of before. As he did in his acclaimed true crime masterwork, The Westies , HC: William Morrow. English The Westies, follows the life and criminal career of Tinh Ngo, a How cheaply he could buy loyalty and affection. As of Oct. Headquartered in Prince Frederick, MD, Recorded Books was founded in as an alternative to traditional radio programming. They are children of the Vietnam War. Reach Us on Instagram. English William Morrow , - Seiten 1 Rezension Throughout the late '80s and early '90s, a gang of young Vietnamese refugees cut a bloody swath through America's Asian underworld. In America, these boys were thrown into schools at a level commensurate with their age, not their educational abilities. The only book on the market that follows a Vietnamese gang in America. Exclusive Bestsellers. -

Teenage Murder Suspects Still at Large by Sompratch Saowakhon Single Arrest Warrant for All Four All Four Are Suspects in the Mit Murder in the Case

Volume 14 Issue 8 News Desk - Tel: 076-236555February 24 - March 2, 2007 Daily news at www.phuketgazette.net 25 Baht The Gazette is published in association with Island-wide security IN THIS ISSUE NEWS: Swiss man stabs po- CCTV now online lice; Two die in head-on By Janyaporn Morel smash. Pages 2 & 3 INSIDE STORY: Patong Beach PHUKET: The next time you are masseuse set ablaze in having a night out on the town in broad daylight. Patong, Kata-Karon or Phuket Pages 4 & 5 City be sure to keep a smile on your face: you might be on TV. AROUND THE NATION: To Don Col Peerayuth Karachedi, Muang or not to Don Muang? Superintendent for Administrative Airlines are divided. Page 8 Affairs at Phuket Provincial Po- AROUND THE SOUTH: More lice Station, told the Gazette on than 30 bombs ring in the February 14 that a closed-circuit Chinese New Year in the television (CCTV) system has Deep South. Page 9 been fully tested and is now op- erational in the three popular PEOPLE: Club diva Barbara Tucker belts out her famous tourist locations. anthems in the name of Love. Each of the three locales Pages 14 & 15 has 16 cameras linked to a com- mand center at a local police sta- AMBROSIA’S SECRETS: Fishing tion in Kathu, Chalong and for compliments nets few re- Phuket City, respectively. sults. Page 17 Installed under a 16-million- WATCHERS WATCHING: Worawit Worrawiboonpong, Manager of CAT Telecom’s Phuket Office, shows LIFESTYLE: Strap-ons and slip- baht contract with telecommuni- cations provider CAT Telecom off the capabilities of the new high-tech surveillance system to Phuket City Police Superintendent Col ons – shoes; U2’s latest Nos Svettalekha at the Phuket City Police Station CCTV Command Center. -

NATIONAL:YOUTH GANG INFORMATION CENTER If You

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. 147234 u.s. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice Thh document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official posilion or policies of the Nalionallnstitute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this FSfg..,-ri material has been granted by Public Domain/U S Senate u.s. Department of Justjcp to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the...., owner. NATIONAL:YOUTH GANG INFORMATION CENTER 4301 North Fairfax Drive, Suite 730 Arlington, Virginia 22203 t 1-800-446-GANG • 703-522-4007 NYGIC Document Number: \:) oo'1l- Permission Codes: ~tpartmtnt n~ ~ufititt STATEMENT OF .. .. ROBERT S. MUELLER, III ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL CRIMINAL DIVISION UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE BEFORE THE SENATE PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE REGA.RDING ASIAN ORGANIZED CRIME NOVEMBER 6, 1991 Mr. Chairman and Members of the Subcommittee, I am pleased to discuss with you today what the Department of &Justice is doing to respond to the threat posed by Asian organized crime groups. We appreciate the interest this Subcommi t'tee has in this important topic and in the support that you have provided to our program on Asian Organized Crime. We were delighted that your staff was able to participate recently at our Asian organized Crime Conference in San Francisco. -

A Retrospective (1990-2014)

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York: A Retrospective (1990-2014) The New York County Lawyers Association Committee on the Federal Courts May 2015 Copyright May 2015 New York County Lawyers Association 14 Vesey Street, New York, NY 10007 phone: (212) 267-6646; fax: (212) 406-9252 Additional copies may be obtained on-line at the NYCLA website: www.nycla.org TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE COURT (1865-1990)............................................................ 3 Founding: 1865 ........................................................................................................... 3 The Early Era: 1866-1965 ........................................................................................... 3 The Modern Era: 1965-1990 ....................................................................................... 5 1990-2014: A NEW ERA ...................................................................................................... 6 An Increasing Docket .................................................................................................. 6 Two New Courthouses for a New Era ........................................................................ 7 The Vital Role of the Eastern District’s Senior Judges............................................. 10 The Eastern District’s Magistrate Judges: An Indispensable Resource ................... 11 The Bankruptcy -

Transcription

Frank Bari Interview, NYS Military Museum Frank Bari Veteran Wayne Clarke Mike Russert Interviewers August 10, 2006 Westbury Public Library Westbury, New York Frank Bari FB Mike Russert MR Wayne Clarke WC FB: (Holding up a framed certificate from the US Coast Guard Auxiliary). It’s so important, and these are all volunteers, just like the Army Guard and the Militia. When I looked at the site, maybe I missed it, but I do think that I mentioned that the US Coast Guard Auxiliary, which is such an important factor. It frees the regulars up, it frees up the reserves. And the work that they were doing, normally you’ll find that the auxiliarists are out giving courses, boating safety, boarding vessels, and doing what the Coast Guard law enforcement, things of that nature. They’re of vital importance to the Coast Guard and part of the Coast Guard family. I guess when that guy signed me up, it may have done me a favor. WC: It sounds like it. MR: Are you ready? FB: Yes. MR: This is an interview at the Westbury Public Library, Westbury, New York. It is the tenth of August 2006, approximately 1 p.m. The interviewers are Mike Russert and Wayne Clarke. Could you give me your full name, date of birth and place of birth, please? FB: My name is Frank Bari. I was born in New York City, New York, born and raised on the Lower East Side in South Brooklyn. Even though they call it Carroll Gardens, it’s still South Brooklyn to me. -

Behind the Scenes Behind the Scenes

COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENTARY COPY ENTARY COPY READ ME TAKE ME COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENT VIETNAM MARCH 2014 1Year Anniversary Issue BRUSHED ASIDE The Disappearing Art of Calligraphy PAGE 30 HOLD THAT POSE Random Acts of Ballet PAGE 32 PARADISE FOR SALE An Island in Hawaii Unlike Any Other Oi PAGE 63 STORY Behind the Scenes 1 2 3 CO M PLIME ENTA N R TAR Y C O PREAD Y ME TAKE ME Y C O PY COMP COMP L IMEN L I M T E N T A R Y C O P A R Y C O P Y COMPLIM Y E NT VIETNAM MARCH 2014 1year Anniversary Issue BRUSHED ASIDE EVERYWHERE YOU GO The Disappearing Art of Calligraphy PAGE 30 HOLD THAT POSE Random Acts of Ballet PAGE 32 PARADISE FOR SALE Director XUAN TRAN An Island in Hawaii Unlike Any Other PAGE 63 Business Consultant ROBERT STOCKDILL oi [email protected] Story 093 253 4090 Behind the Scenes Managing Editor CHRISTINE VAN 1 [email protected] This Month’s Cover Deputy Editor JAMES PHAM Image: Adam Robert Young [email protected] Model: Tran Hoang Yen Researcher GEORGE BOND [email protected] Associate Publisher KHANH NGUYEN [email protected] Graphic Artists HIEN NGUYEN [email protected] NGUYEN PHAM [email protected] Staff Photographers ADAM ROBERT YOUNG NGOC TRAN Publication Manager HANG PHAN [email protected] 097 430 9710 For advertising please contact: KATE TU [email protected] 091 800 7160 NGAN NGUYEN [email protected] 090 279 7951 JIMMY VAN DER KLOET [email protected] 094 877 9219 JULIAN AJELLO [email protected] ƠI VIỆT NAM 093 700 9910 NHÀ XUẤT BẢN THANH NIÊN CHAU NGUYEN Chịu trách nhiệm xuất bản: Đoàn -

The Vegetarian Issue

COMPLIMENTARY COPY ENTARY COPY READ ME TAKE ME COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENT VIETNAM AUGUST 2014 The Vegetarian Issue HOPE FLOATS Addressing Vietnam's Drowning Epidemic PAGE 20 THE RELIGION OF BARBECUE Delicious Finger Licking Ribs and Chicken PAGE 46 1 Why we love a mess A great BIS teacher is: Because at ISHCMC we 50% Innovator understand that sometimes you 50% Entertainer have to get your hands a little 50% Motivator messy to be truly innovative. And is apparently able to defy the laws of mathematics. Today’s students need to do more than memorise information in traditional classrooms. They need a more evolved approach to education that allows them the freedom to pursue their passions fearlessly. In addition to a strong academic foundation, they need opportunities to be creative, innovative and analytical, all of which lie at the heart of the ISHCMC philosophy. Dedicated, skilled and well-qualified teachers, with relevant British curriculum experience, ensure that the education on offer is amongst the very best available anywhere in the world. BIS teachers inspire students to make the best of their abilities – including solving Come and see impossible maths equations like the one above. the difference we can make in your child’s life. Where is your child going? The only school in HCMC fully accredited to offer all 3 International Baccalaureate programmes for students aged 2 - 18 years. Hanoi: www.bishanoi.com 28 Vo Truong Toan, District 2 Ho Chi Minh City: www.bisvietnam.com Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Tel: +84 (8) 3898-9100 Email: [email protected] www.ishcmc.com 2 Carla, Grade 4 & Ella, Grade 1 ISHCMC Students A great BIS teacher is: 50% Innovator 50% Entertainer 50% Motivator And is apparently able to defy the laws of mathematics. -

Issue – April 2014

COMPLIMENTARY COPY ENTARY COPY READ ME TAKE ME COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENT NOTHING HIDDEN, EVERYTHING SACRED Saigon in Sketches PAGE 24 VIETNAM APRIL 2014 MISTRESS OF MAYHEM Vietnam's Notorious Female Crime Boss PAGE 30 THE PUPPET MASTER A Delicious Mix of Culture and Food PAGE 46 ISLAND LIFE Paradise Found in Nusa Lembongan PAGE 62 Love and Marriage in VIETNAM 1 2 3 CO M PLIME ENTA N R TAR Y C O PREAD Y ME TAKE ME Y C O PY COMP COMP L IMEN L I M T E N T A R Y C O P A R Y C O P Y COMPLIM Y E NT NOTHING HIDDEN, EVERYTHING SACRED Saigon in Sketches PAGE 30 VIETNAM APRIL 2014 MISTRESS OF MAYHEM Vietnam's Notorious Female Crime Boss PAGE 30 THE PUPPET MASTER A Delicious Mix of Culture and Food EVERYWHERE YOU GO PAGE 30 ISLAND LIFE Paradise Found in Nusa Lembongan PAGE 30 Director XUAN TRAN Business Consultant ROBERT STOCKDILL Love and Marriage in [email protected] VIETNAM 093 253 4090 Managing Editor CHRISTINE VAN 1 [email protected] This Month’s Cover Deputy Editor JAMES PHAM Image: Quinn Ryan Mattingly [email protected] Researcher GEORGE BOND [email protected] Associate Publisher KHANH NGUYEN [email protected] Graphic Artists HIEN NGUYEN [email protected] NGUYEN PHAM [email protected] Staff Photographers ADAM ROBERT YOUNG NGOC TRAN For advertising please contact: KATE TU [email protected] 091 800 7160 NGAN NGUYEN [email protected] 090 279 7951 JIMMY VAN DER KLOET [email protected] 094 877 9219 CHAU NGUYEN [email protected] 091 440 0302 ƠI VIỆT NAM PHUONG TRAN NHÀ XUẤT BẢN THANH NIÊN [email protected] -

REPORT 2D Session HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES 104–556 "!

104TH CONGRESS REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 104±556 "! ANTICOUNTERFEITING CONSUMER PROTECTION ACT OF 1995 MAY 6, 1996.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. MOORHEAD, from the Committee on the Judiciary, submitted the following REPORT [To accompany H.R. 2511] [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on the Judiciary, to whom was referred the bill (H.R. 2511) to control and prevent commercial counterfeiting, and for other purposes, having considered the same, report favorably thereon without amendment and recommend that the bill do pass. CONTENTS Page Purpose and Summary ............................................................................................ 1 Background and Need for Legislation .................................................................... 2 Hearings ................................................................................................................... 4 Committee Consideration ........................................................................................ 4 Committee Oversight Findings ............................................................................... 4 Committee on Government Reform and Oversight Findings ............................... 5 New Budget Authority and Tax Expenditures ...................................................... 5 Congressional Budget Office Estimate ................................................................... 5 Inflationary Impact Statement -

An Examination of the Booming International Trade in Counterfeit Luxury Goods and an Assessment of the American Efforts to Curtail Its Proliferation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Fordham University School of Law Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 17 Volume XVII Number 2 Volume XVII Book 2 Article 5 2006 The Hoods Who Move the Goods: An Examination of the Booming International Trade in Counterfeit Luxury Goods and an Assessment of the American Efforts to Curtail Its Proliferation Sam Cocks Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Sam Cocks, The Hoods Who Move the Goods: An Examination of the Booming International Trade in Counterfeit Luxury Goods and an Assessment of the American Efforts to Curtail Its Proliferation, 17 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 501 (2006). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol17/iss2/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Hoods Who Move the Goods: An Examination of the Booming International Trade in Counterfeit Luxury Goods and an Assessment of the American Efforts to Curtail Its Proliferation Cover Page Footnote Professor Abraham -

February 2014

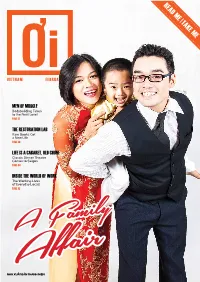

COMPLIMENTARY COPY ENTARY COPY READ ME TAKE ME COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENT VIETNAM FEBRUARY 2014 MEN OF MUSCLE Bodybuilding Taken to the Next Level PAGE 27 THE RESTORATION LAB Rare Books Get a New Life PAGE 30 LIFE IS A CABARET, OLD CHUM Classic Dinner Theater Comes to Saigon PAGE 44 INSIDE THE WORLD OF WORK The Working Lives of Everyday Locals PAGE 92 A Family Affair 1 2 3 CO M PLIME ENTA N R TAR Y C O PREAD Y ME TAKE ME Y C O PY COMP COMP L IMEN L I M T E N T A R Y C O P A R Y C O P Y COMPLIM Y E NT VIETNAM FEBRUARY 2014 MEN OF MUSCLE Bodybuilding Taken to the Next Level PAGE 27 THE RESTORATION LAB Rare Books Get EVERYWHERE YOU GO a New Life PAGE 30 LIFE IS A CABARET, OLD CHUM Classic Dinner Theater Comes to Saigon PAGE 44 INSIDE THE WORLD OF WORK The Working Lives of Everyday Locals PAGE 92 Director XUAN TRAN A Family Business Consultant ROBERT STOCKDILL [email protected] Affair 093 253 4090 1 Managing Editor CHRISTINE VAN [email protected] This Month’s Cover Image: Ngoc Tran Deputy Editor JAMES PHAM Model: The Tran Family [email protected] Make Up: Huyen Phan Researcher GEORGE BOND [email protected] Associate Publisher KHANH NGUYEN [email protected] Graphic Artist HIEN NGUYEN [email protected] Staff Photographers NGOC TRAN ADAM ROBERT YOUNG Publication Manager HANG PHAN [email protected] 097 430 9710 For advertising please contact: JULIAN AJELLO [email protected] 093 700 9910 NGAN NGUYEN [email protected] 090 279 7951 ƠI VIỆT NAM JIMMY VAN DER KLOET [email protected] NHÀ XUẤT BẢN THANH