Matisse and the Understanding of Kuba Pattern. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C O Ra G in Sb U R G Mo De

CORA GINSBURG • MODERN TITI HALLE CORA GINSBURG LLC A Catalogue of 20th century costume & textiles 2018 by appointment 19 East 74th Street tel 212-744-1352 New York, NY 10021 fax 212-879-1601 www.coraginsburg.com [email protected] LES JETS D’EAU RAYON AND COTTON WALL COVERING BY EDOUARD BÉNÉDICTUS FOR BRUNET-MEUNIÉ French, 1925 Edouard Bénédictus (1878–1930) is known today primarily for his textile, wallpaper, and carpet designs. However, over the course of his prolific career spanning the first three decades of the twentieth century, from the Art Nouveau to the Art Deco movements, he was also a chemist, musician, composer, poet, critic, and theatrical costume designer. Born in Paris, Bénédictus entered the École des Arts Décoratifs in 1897 and, in 1900, he traveled to Darmstadt, Germany, to study chemistry, an interest that he continued to pursue after his return to Paris. Between 1900 and 1910, he worked primarily in cuir incrusté (inlaid leather), a technique for which he became well known; his panels and boxes featuring flowers, birds, and animals were regularly exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Décorateurs. He also provided the illustrations for a series of articles by the artist Maurice Verneuil for Art et Décoration on adapting motifs from nature for decorative purposes. Bénédictus’s renderings of insects, reptiles, and butterflies reflect the sinuous, organic forms of the Art Nouveau style. The 1920s represent the high point of Bénédictus’s professional career in terms of his contribution to the Art Deco aesthetic and his public recognition. He produced gouaches with repeating patterns for large-format hand-colored pochoir albums: Variations (1924), Nouvelles Variations (1926), and Relais (published posthumously in 1930). -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016" (2016). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 73. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/73 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 28. NUMBER 1. SPRING, 2016 TSA Board Member and Newsletter Editor Wendy Weiss behind the scenes at the UCB Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, durring the TSA Board meeting in March, 2016 Spring 2016 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (Membership & Communications Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives. -

A Weaver Looks at Tinguian Blankets

Textile VOLUME 23 n NUMBER 3 n FALL, 2011 Society of Symposium 2012 news on Page 2 America A Weaver Looks at Tinguian Blankets Kathleen Forance Johnson with Yushan Tsai CONTENTS N 1898 THE AMERICAN they enjoyed some of the new Cole (1881-1961), to take up Commodore, George Dewey, amenities offered, but Benedict the challenge. Cole studied 1 A Weaver Looks at Tinguian defeated the Spanish fleet in deplored that their original cultures a group of isolated and little- Blankets I the Battle of Manila Bay, ending would never again be seen in known mountain people from 2 Symposium 2012 News the period of Spanish domination their undisturbed, natural settings. 1907-1908 during a stay of 16 3 From the President of the Philippines, and the Worse yet, those cultures months for the Field Columbian 4 TSA News, TSA Member News archipelago was annexed by had not been systematically Museum. the United States of America. In documented in those original Cole called these people 6 Conference Reviews the early years of the American settings by professional observers. Tinguian but they have always 10 Tinguan Blankets, Continued Colonial Period, anthropolo- referred to themselves as 14 Textile Community News gist Laura E Benedict was “Itneg” and that is how they working to document indig- are known in much of the 15 In Memoriam: Ardis James enous tribal cultures in the literature. Here we have 16 Book Reviews southern Philippines. In 1907 used the terms interchange- 17 Exhibition Reviews she wrote an urgent letter, ably. At Cole’s time, the now in the Field Museum Tinguian/Itneg were among 20 Calls for Papers, Calendar archives, to Dr. -

01 PAG ING 30-03-2012 11:40 Pagina 1

01 PAG ING 30-03-2012 11:40 Pagina 1 Reading Ghereh opens a window on the world of rugs. One of the few international magazines dedicated to textiles arts and the art of Oriental rugs, Ghereh gives a voice to many elements of these ancients arts. Elements of beauty, harmony and peace. 02-03 SOMMARIO ing 30-03-2012 11:41 Pagina 2 ISSUE N.50 INTERNATIONAL CARPET & TEXTILE REVIEW 67 TRANSYLVANIAN RUGS The collection of St. Margaret’s Church in Mediash Stefano Ionescu An original study of the Anatolian rugs to be found in Transylvania, and the fine examples conserved in the churches of the region. 21 THE MULBERRY The Silk Road Taher Sabahi Silk, its origins, its distribution th- rough Europe and Italy told through the history of an ancient tree. 33 THE ICOC CONFERENCE A review R. John Howe An account of the 12th ICOC Confe- rence, its meetings and market news. A review of the three temporary exhi- bitions organised for the occasion: the display of rare Turkoman rugs; a collection of Oriental carpets from private Swedish collections and, fi- nally, an exhibition dedicated entirely to Scandinavian textiles. 2 02-03 SOMMARIO ing 3-04-2012 10:40 Pagina 3 INTERNATIONAL CARPET & TEXTILE REVIEW News 50 News and updates from leading museums in Europe and the United States: from the nomination of the new director of the MAK in Vienna to the new layout of the gallery de- dicated to Islamic art at the Metropolitan Museum of New York. Exhibitions 56 There are plenty of exhibitions reviewed in this issue. -

The Inner Eye Vision and Transcendence in African Arts

exhibition preview The Inner Eye Vision and Transcendence in African Arts Mary Nooter Roberts “e Inner Eye” draws attention to African individuals, such as “THE INNER EYE: rulers, mothers, and healers, as well as spirit beings who exhibit VISION AND TRANSCENDENCE IN AFRICAN ARTS” heightened senses of awareness, while acknowledging artists and CURATED BY MARY NOOTER ROBERTS performers as visionaries who bring works to life. A number of LOS ANGELES COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART artists are identiable master hands, and in some cases sculptures RESNICK PAVILION, FEBRUARY 26—JULY 9, 2017 are shown in clusters to appreciate the remarkable ingenuity that Oro, the essence of communication, takes place in the eyes. each artist brings to a single genre. Ultimately, in their own set- (Yoruba axiom cited in Abiodun :) tings and, one can hope, museum spaces as well, these objects empower people to transcend human limitations and boundaries he Inner Eye: Vision and Transcendence in and envision their own potentialities and possibilities (Fig. ). African Arts” features a cross-cultural con- Most works of art encourage viewers to gaze upon them in all stellation of sculptures—many of them iconic their multidimensionality. In fact, museum experience is predi- in the corpus of African art—and eye-catching cated upon looking. When we see art in most Western museum textiles. e exhibition explores how works of settings, the assumption is that objects are meant to be scruti- art and the visual regimes through which they nized and beheld, and in a sense consumed by visitors’ eyes and have been created and performed enable transitions from one caressed by their gaze. -

Textiles Department Records BMA.18 Finding Aid Prepared by Anna J

Textiles Department Records BMA.18 Finding aid prepared by Anna J. Clarkson, Tracy Lewis, and Waneta Gagne This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit October 18, 2016 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Generously supported with funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) and Frick Foundation Archives and Manuscripts Collections, The Baltimore Museum of Art October 5, 2016 10 Art Museum Drive Baltimore, MD, 21032 (443) 573-1778 [email protected] Textiles Department Records BMA.18 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Institutional History....................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... -

Coming to Terms with Heritage Kuba Ndop and the Art School of Nsheng

Coming to Terms with Heritage Kuba Ndop and the Art School of Nsheng Elisabeth L. Cameron n 1989, I was in Zaïre (now the Democratic Republic of feet. For example, Shyaam aMbul aNgoong banned gambling and the Congo) doing pre-dissertation fieldwork and trying introduced the lyeel game (Vansina 1978:60). He is also credited to find the perfect research topic. The Kuba kingdom for bringing a time of peace that gave people leisure time to play was an irresistible draw and I spent several months in games. Therefore, he chose thelyeel game as his symbol. Thendop the area exploring various topics. I was especially privi- was used during the king’s lifetime as his surrogate when he was leged to stay at Nsheng,1 the capital of the Kuba king- absent from the capital. At his death, the incoming king slept with dom, as the guest of the king’s mother. One evening a young man the ndop of the previous king to absorb his ngesh or bush spirit.3 Iapproached me and gave me an ndop, a carved figure represent- The ndop then became a memorial figure that was kept by the ing the seventeenth century king Shyaam aMbul aNgoong (Fig. king’s surviving wives and occasionally displayed. When the Afri- 1). He introduced himself as Musunda-Kananga from the Sala can American missionary William Sheppard arrived at the court Mpasu area and heritage and explained that he had aspirations in 1892, he described the scene: of becoming a contemporary artist. He had applied to go to the On an elevation were statues of four former kings. -

Weaving Books and Monographs

Tuesday, September 10, 2002 Page: 1 ---. 10 Mujeres y Textil en 3d/10 Women and Textile Into 3. [Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. Galeria Aristos, 1975], 1975. ---. 10 Mujeres y Textil en 3d/10 Women and Textile Into 3. [Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. Galeria Aristos, 1975], 1975. ---. 100 Jahre J. Hecking; Buntspinnerei und Weberei. Wiesbaden, Verlag f?r Wirtschaftspublizistik Bartels, 1958. ---. 100 Years of Native American Arts: Six Washington Cultures. [Tacoma, Washington: Tacoma Art Museum, 1988], 1988. ---. 1000 [i.e. Mil] Años de Tejido en la Argentina: [Exposici?n] 24 de Mayo Al 18 Junio de 1978. Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura y Educaci?n, Secretaría de Cultura, Instituto Nacional de Antropología, 1978. ---. 1000 Years of Art in Poland. [London, Great Britain: Royal Academy of Arts, 1970], 1970. ---. 101 Ways to Weave Better Cloth: Selected Articles of Proven Interest to Weavers Chosen from the Pages of Textile Industries. Atlanta, GA.: Textile Indistries, 1960. ---. 125 Jahre Mech. Baumwoll-Spinnerei und Weberei, Augsburg. [Augsburg, 1962. ---. 1977 HGA Education Directory. West Hartford, CT: Handweavers Guild of America, 1978. ---. 1982 Census of Manufactures. Preliminary Report Industry Series. Weaving Mills. [Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of, 1984. ---. 1987 Census of Manufactures. Industry Series. Weaving and Floor Covering Mills, Industries 2211, 2221, 2231, 2241, and 2273. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of, 1990. ---. 1987 Census of Manufactures. Preliminary Report. Industry Series. Weaving and Floor Covering Mills: Industries 2211, 2221, 2241, and 2273. [Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of, 1994. ---. 1992 Census of Manufactures. -

Coming to Terms with Heritage Kuba Ndop and the Art School of Nsheng

Coming to Terms with Heritage Kuba Ndop and the Art School of Nsheng Elisabeth L. Cameron Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/afar/article-pdf/45/3/28/1816145/afar_a_00009.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 n 1989, I was in Zaïre (now the Democratic Republic of feet. For example, Shyaam aMbul aNgoong banned gambling and the Congo) doing pre-dissertation fieldwork and trying introduced the lyeel game (Vansina 1978:60). He is also credited to find the perfect research topic. The Kuba kingdom for bringing a time of peace that gave people leisure time to play was an irresistible draw and I spent several months in games. Therefore, he chose thelyeel game as his symbol. Thendop the area exploring various topics. I was especially privi- was used during the king’s lifetime as his surrogate when he was leged to stay at Nsheng,1 the capital of the Kuba king- absent from the capital. At his death, the incoming king slept with dom, as the guest of the king’s mother. One evening a young man the ndop of the previous king to absorb his ngesh or bush spirit.3 Iapproached me and gave me an ndop, a carved figure represent- The ndop then became a memorial figure that was kept by the ing the seventeenth century king Shyaam aMbul aNgoong (Fig. king’s surviving wives and occasionally displayed. When the Afri- 1). He introduced himself as Musunda-Kananga from the Sala can American missionary William Sheppard arrived at the court Mpasu area and heritage and explained that he had aspirations in 1892, he described the scene: of becoming a contemporary artist. -

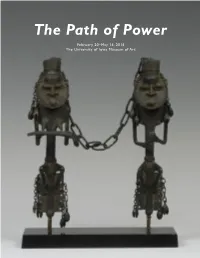

The Path of Power

The Path of Power February 20–May 15, 2016 The University of Iowa Museum of Art This guide is published in conjunction with “Social (In)Justice,” curated by Dale Fisher, Curator of Education. The exhibition is on view in the Black Box Theater at the Iowa Memorial Union, from February 20 through May 15, 2016. Funding for the exhibition was provided in part by Deborah & Rod Zeitler and the UIMA Members Special Exhibition Fund. As part of the main exhibition, “The Path of Power” was curated by Cory Gundlach, Associate Curtator of African and Non-Western Art. Photography for the exhibition was provided by Steve Erickson. El Anatsui (Ghanaian, b. 1944– ) Transit, 2002 Wood, pigment 10.16 x 60.96 cm (4 x 24 in.) Purchased with funds from the Stanley-UI Foundation Support Organization, 2002.106a–o The Path of Power explores social justice in Africa through objects that support the expression of authority, status, and archetype. Upholding these aspects of identity commonly relies upon the creative display of privilege and exclusion, which are central to the politics of equality. These objects were created for spirits, elites, initiates, colonists, and art collectors. Regardless of sacred or secular context, settings that surround each object emphasize social mobility as integral to artistic function. In this sense, these examples of African art both create and become the path that leads to a change or preservation of identity. The visionary quality and exceptional skill with which these objects were made demonstrates the power of artistic imagination to shape and define identity and status in Africa. -

The Ornaments of Shoowa Kuba

The Ornaments of Shoowa Kuba: A digital re-interpretation of a textile art Sabri Gokmen Georgia Institute of Technology, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper will discuss how Shoowa Kuba textiles could be analyzed as an ornament that can be digitally constructed and applied in design. An historical outline of ornament is provided by briefly comparing Classical and Gothic ornaments. This theoretical framework is then compared to the art of Shoowa Kuba focusing on their textile embroideries. Various patterns and techniques will be introduced showing how Kuba people implement rules as well as how they break them. These patterns will be digitally reconstructed to show their applicability to the digital design domain. KEYWORDS: Digital design research, textile patterns, ornaments, scripting. 79 1. The World of Ornament This expressive and abstract character of ornament is exemplified by specific African tribal textile art where Up until the 20th century, there was a constant desire intricate and playful patterns emerge out from a woven for the use and transformation of ornament in art and scheme. The Shoowa Kuba embroideries which will architecture. In many historical architectural styles be the main focus of discussion in this paper, will be such as the Gothic and Renaissance, ornament has analyzed in order to reveal their proximity to the behavior been central to design while its relation to structure of Gothic ribs. In Shoowa Kuba art, the playful usage of has varied. In Classical architecture, this notion simple geometric lines produce dramatic and surprising transformed the abstract lines of structure to smooth patterns that gives each cloth an aesthetic quality. -

KUBA Fabric of an Empire

ART on view KUBA Fabric of an Empire By Kevin Tervala, Matthew S. Polk Jr., and Amy L. Gould FIG. 1 (left): Detail of On the southern edge of the overskirt shown in fi g. 12. Congolese River Basin, nestled between the Kasai and Sankuru Rivers, a remarkable king- dom fl ourished in the latter half of the second millennium CE. Known to their neighbors as “Kuba,” these “people of the king” developed one of the greatest civilizations in the history of central Africa. At the apex of its power in the mid to late nineteenth century, the Kuba king- dom contained all the features of a modern-day nation-state: a professional bureaucracy, a sys- tem of taxation, extensive provision of public goods, a constitution (albeit unwritten), and a sophisticated legal system featuring trial by jury and courts of appeal.1 Art and design were central to life in this king- dom. In addition to developing an elaborate and varied masquerade tradition, Kuba men and women were prolifi c textile artists. Hous- es were woven, currency was embroidered, and an individual’s wealth and power were refl ected in the intricacy of the patterns sewn, dyed, and embroidered onto their clothing. Like words on a page, these dazzling designs tell the history of the polity as clearly as any written account or oral history. Scholars have long recognized the potential of Kuba art to shed a brighter light on the kingdom’s past. Yet, as the eminent Belgian 74 XXIII-1 AOV Kuba E+F.indd 74 08/11/18 16:56 historian Jan Vansina fi rst noted in 1978, “any FIG.