Platonic Cosmopolitanism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diogenes Laertius, Vitae Philosophorum, Book Five

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter 12-1986 The Lives of the Peripatetics: Diogenes Laertius, Vitae Philosophorum, Book Five Michael Sollenberger Mount St. Mary's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Ancient Philosophy Commons, and the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Sollenberger, Michael, "The Lives of the Peripatetics: Diogenes Laertius, Vitae Philosophorum, Book Five" (1986). The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter. 129. https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp/129 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. f\îc|*zx,e| lîâ& The Lives of the Peripatetics: Diogenes Laertius, Vitae Philosoohorum Book Five The biographies of six early Peripatetic philosophers are con tained in the fifth book of Diogenes Laertius* Vitae philosoohorum: the lives of the first four heads of the sect - Aristotle, Theophras tus, Strato, and Lyco - and those of two outstanding members of the school - Demetrius of Phalerum and Heraclides of Pontus, For the history of two rival schools, the Academy and the Stoa, we are for tunate in having not only Diogenes' versions in 3ooks Four and Seven, but also the Index Academicorum and the Index Stoicorum preserved among the papyri from Herculaneum, But for the Peripatos there-is no such second source. -

A History of Cynicism

A HISTORY OF CYNICISM Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com A HISTORY OF CYNICISM From Diogenes to the 6th Century A.D. by DONALD R. DUDLEY F,llow of St. John's College, Cambrid1e Htmy Fellow at Yale University firl mll METHUEN & CO. LTD. LONDON 36 Essex Street, Strand, W.C.2 Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com First published in 1937 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com PREFACE THE research of which this book is the outcome was mainly carried out at St. John's College, Cambridge, Yale University, and Edinburgh University. In the help so generously given to my work I have been no less fortunate than in the scenes in which it was pursued. I am much indebted for criticism and advice to Professor M. Rostovtseff and Professor E. R. Goodonough of Yale, to Professor A. E. Taylor of Edinburgh, to Professor F. M. Cornford of Cambridge, to Professor J. L. Stocks of Liverpool, and to Dr. W. H. Semple of Reading. I should also like to thank the electors of the Henry Fund for enabling me to visit the United States, and the College Council of St. John's for electing me to a Research Fellowship. Finally, to• the unfailing interest, advice and encouragement of Mr. M. P. Charlesworth of St. John's I owe an especial debt which I can hardly hope to repay. These acknowledgements do not exhaust the list of my obligations ; but I hope that other kindnesses have been acknowledged either in the text or privately. -

Pythagorean Music in Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy

32 RAMIFY 8.1 (2019) “How Pythagoras Cured by Music”: Pythagorean Music in Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy KIMBERLY D. HEIL Interpretive schemata for reading Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy are plentiful. Some of the more popular of those schema read the work along the divided line from Plato’s Republic, taking as programmatic the passage from Book Five in which Boethius discusses the ways in which man comes to know through sensation first, then imagination, then reason, and finally understanding.1 Others read the work as Mneppian Satire because of its prosimetron format. Some scholars study character development in the KIMBERLY D. HEIL is a PhD candidate in Philosophy at the Institute of Philosophic Studies at the University of Dallas; she received a BA in Philosophy from the University of Nebraska at Kearney and an MA in Philosophy from the University of South Florida. She is currently a Wojtyła Graduate Teaching Fellow at the University of Dallas, where she teaches core curriculum philosophy classes. She is writing a dissertation on the relationship between philosophy and Christianity in Augustine of Hippo’s De Beata Vita. The title of this piece is taken from a section subtitle in the work The Life of Pythagoras by the second-century Neopythagorean Iamblichus. 1 See, for instance, McMahon, Understanding the Medieval Meditative Ascent, 215. He references two other similar but competing interpretations using the same methodology. “How Pythagoras Cured by Music” : HEIL 33 work as it echoes Platonic-style dialogues. Still others approach the work as composed of several books, each representing a distinct school of philosophy.2 Furthermore, seeing it as an eclectic mixture of propositions from various schools of philosophy re-purposed and molded to suit Boethius’s own needs, regardless of the literary form and patterns, is commonly agreed upon in the secondary literature. -

ON PLATO's CONCEPT of REASON by M. Cole Powers, BA, Philosophy

ON PLATO’S CONCEPT OF REASON By M. Cole Powers, B.A., Philosophy (McGill 2013) A thesis presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of PHILOSOPHY Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2016 © M. Cole Powers 2016 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I, Cole Powers, hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii ON PLATO’S CONCEPT OF REASON MATHEW COLE POWERS MASTER OF ARTS ‐ PHILOSOPHY 2016 RYERSON UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT What is reason? A number of contemporary philosophical schools of thought have sought, implicitly or explicitly, to answer the question. That an answer to the question be found is of utmost importance for the practice of philosophy, and yet none seems to be forthcoming. In this thesis, we propose to examine Plato’s concept of reason. Our method in the thesis, however, is to proceed negatively: first, we examine the misology passage from the Phaedo 89d: why is the greatest evil to become a misologue (hater of reason)? What does this say about Plato’s conception of reason? What is the connection between reason, pleasure, and pain? Next, we move to the Phaedrus, where a more constructive account is offered. -

Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans1

Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans1 Historically, the name Pythagoras meansmuchmorethanthe familiar namesake of the famous theorem about right triangles. The philosophy of Pythagoras and his school has become a part of the very fiber of mathematics, physics, and even the western tradition of liberal education, no matter what the discipline. The stamp above depicts a coin issued by Greece on August 20, 1955, to commemorate the 2500th anniversary of the founding of the first school of philosophy by Pythagoras. Pythagorean philosophy was the prime source of inspiration for Plato and Aristotle whose influence on western thought is without question and is immeasurable. 1 c G. Donald Allen, 1999 ° Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans 2 1 Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans Of his life, little is known. Pythagoras (fl 580-500, BC) was born in Samos on the western coast of what is now Turkey. He was reportedly the son of a substantial citizen, Mnesarchos. He met Thales, likely as a young man, who recommended he travel to Egypt. It seems certain that he gained much of his knowledge from the Egyptians, as had Thales before him. He had a reputation of having a wide range of knowledge over many subjects, though to one author as having little wisdom (Her- aclitus) and to another as profoundly wise (Empedocles). Like Thales, there are no extant written works by Pythagoras or the Pythagoreans. Our knowledge about the Pythagoreans comes from others, including Aristotle, Theon of Smyrna, Plato, Herodotus, Philolaus of Tarentum, and others. Samos Miletus Cnidus Pythagoras lived on Samos for many years under the rule of the tyrant Polycrates, who had a tendency to switch alliances in times of conflict — which were frequent. -

Ancient Greek Philosophy. Part 1. Pre-Socratic Greek Philosophers

Ancient Greek Philosophy. Part 1. Pre-Socratic Greek philosophers. The pre-Socratic philosophers rejected traditional mythological explanations for the phenomena they saw around them in favor of more rational explanations. Many of them asked: From where does everything come? From what is everything created? How do we explain the plurality of things found in nature? How might we describe nature mathematically? The Milesian school was a school of thought founded in the 6th Century BC. The ideas associated with it are exemplified by three philosophers from the Ionian town of Miletus, on the Aegean coast of Anatolia: Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes. They introduced new opinions contrary to the prevailing viewpoint on how the world was organized. Philosophy of nature These philosophers defined all things by their quintessential substance (which Aristotle calls the arche) of which the world was formed and which was the source of everything. Thales thought it to be water. But as it was impossible to explain some things (such as fire) as being composed of this element, Anaximander chose an unobservable, undefined element, which he called apeiron. He reasoned that if each of the four traditional elements (water, air, fire, and earth) are opposed to the other three, and if they cancel each other out on contact, none of them could constitute a stable, truly elementary form of matter. Consequently, there must be another entity from which the others originate, and which must truly be the most basic element of all. The unspecified nature of the apeiron upset critics, which caused Anaximenes to define it as being air, a more concrete, yet still subtle, element. -

2016 Actc Proceedings

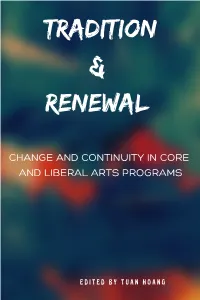

TRADITION & RENEWAL TRADITION AND RENEWAL: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN CORE AND LIBERAL ARTS PROGRAMS Selected Papers from the Twenty-Second Annual Conference of the Association of Core Texts and Courses, Atlanta, April 14–17, 2016 Edited by Tuan Hoang Association for Core Texts and Courses ACTC Liberal Arts Institute 2021 Acknowledgments (Park) CREDIT LINE: Excerpt(s) from THE BIRTH OF TRAGEDY AND THE CASE OF WAGNER by Friedrich Nietzsche, translated by Walter Kaufmann, translation copyright © 1967 by Walter Kaufmann. Used by permission of Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. (McGrath) Excerpt(s) from THE SPIRIT OF THE LAWS by Montesquieu, translated and edited by Anne M. Cohler, Basia Carolyn Miller, and Harold Samuel Stone, translation copyright © 1989 by Anne M. Cohler, Basia Carolyn Miller, and Harold Samuel Stone. Used by permission of Cambridge University Press. All rights reserved. (Galaty) Excerpt(s) from DISCOVERIES AND OPINIONS OF GALILEO by Galileo, translated by Stillman Drake, translation copyright © 1957 by Stillman Drake. Used by permission of Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Contents Introduction: Core Texts and Tradition in Atlanta Tuan Hoang ix Tradition Juxtaposed and Complicated The Oral Voice in Ancient and Contemporary Texts Jay Lutz 3 On the Unity of the Great French Triumvirate John Ray 7 Burke, MacIntyre, and Two Concepts of Tradition Wade Roberts 13 Happiness as a Moral End: On Prudence in Kant’s Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals and Austen’s Persuasion Jane Kelley Rodehoffer 19 “The Stranger God” and the “Artistic Socrates”: On Nietzsche and Plato in Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice Julie Park 27 The Human Person in Core Texts Unheroic Heroes: Ambiguous Categories in Three Core Texts Michael D. -

Empedocles 8

ONE EMPEDOCLES 8 EMPEDOCLES OLYMPIAN Empedocles’ dive into Etna has fascinated scholars, poets, and artists from ancient to modern times. Diogenes Laertius was so taken with it, in fact, that he gives two versions of the event. Biographically speaking, the story becomes even more fascinating as it becomes ever more clear that Emped- ocles was destined to leave the world precisely in this manner, his fate determined by biographers and historians and ultimately through his own writing. Empedocles’ philosophical works, the Purifications and the Phys- ics, were considered raw autobiographical data fit for the gleaning, and the manner in which Empedocles’ philosophy was transformed into his biography reveals more about ancient biographers, such as Diogenes Laer- tius, than it does about Empedocles. Out of the philosophy itself grew a legend that has haunted and intrigued us through the years. There was a tendency in the ancient world, by no means restricted to the biographers, to approach any given text as biographical.1 The poets were favorite subjects of this approach: Homer’s life was pieced together 12 Empedocles 13 from the Iliad and the Odyssey; Aeschylus was presumed to have fought at Salamis because he describes that battle in his Persians.2 The same is true of the philosophers in general, and for Empedocles and other archaic philosophers specifically, because of their use of the first-person “I” in their work. For our purposes, the pursuit of a biographical tradition that emerges from a philosopher’s work, the life of Empedocles is particularly instructive. First, because Empedocles was such a popular figure for the biographers, they have given us an enormous amount of biography to work with. -

Pythagorean Teachings Across the Centuries

Pythagorean Teachings across the Centuries Angela Tripodi, adapted and expanded by the Rosicrucian Research Library Staff and Friends he school of Pythagoras has been defined by Vincenzo Capparelli and by several Tother authors, as the “Greatest school of Wisdom of the West.” It has had profound influence across time and has contributed to providing the coordination needed to combine the search for mystical truth with a clear methodology of wisdom. Even if the inheritance of the Pythagorean tradition cannot be fully grasped, due to its initiatory character, The last-remaining column of the temple dedicated to Hera which required a severe selection process and Lacinia in Crotona, Italy. Photo by Sandro Baldi. involved the obligation of absolute silence of teachings until the very last degrees. The from its Neophyte members, it is still possible few initiates able to enter the last doorway to relive the outlines of the sacred knowledge obeyed the sacred promise of absolute silence. in the teachings. Several sources need to be This norm of silence was the secret of the consulted in order to retrace the spread of school and is mentioned in several sources. this inspired wisdom whose light reached It also implies that all especially profound far from its original source. According to information and teachings were hidden, the information transmitted by Porphyry, not only from outsiders, but also from the Iamblichus, and in part by Diogenes Laertius, participants of the lower degrees. when the school at Crotona1 was destroyed, As is well known, the school had its many essential concepts were lost forever. -

Pythagoras Him.Self Discovered the Pythagorean Theorem

the Pythagorean theorem. I may as well break the news right away: there's no good literary character-a vessel for the ideas and imaginings of other people. And while evidence that Pythagoras him.self discovered the Pythagorean theorem. It was, we like to think we have some reasonably vivid idea of the real Socrates, thanks to however, known to his followers, the Pythagoreans. That rather sets the tone for Plato and other authors like the historian Xenophon, in the case of Pythagoras we the rest of our discussion of Pythagoras. We know a great deal about the tradition of are really just sifting through legends and myths. Not only is Pythagoras quite a Pythagoreans which takes its name fromhim, but we know hardly anything about bit earlier than Socrates, but his way of doing philosophy-if he did philosophy at the man himself. Among the Pre-Socratics, all of whom are surrounded by a good all-was a lot less public than Socrates'. Whereas Socrates would walk up to people deal of misinformation and legend, he stands out as the one figure who is more in the marketplace and harass them by askingthem to define virtue, Pythagoras and myth than man. But what a myth! He's credited with being the first to fuse his young students in Croton supposedly observeda code of silence, to prevent their philosophy and mathematics, with being a worker of miracles, being divine or secret teachings from being divulged to the uninitiated. Of course, maybe that code semi-divine, the son of either Apollo or Hermes. -

Women in Early Pythagoreanism

Women in Early Pythagoreanism Caterina Pellò Faculty of Classics University of Cambridge Clare Hall February 2018 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Alla nonna Ninni, che mi ha insegnato a leggere e scrivere Abstract Women in Early Pythagoreanism Caterina Pellò The sixth-century-BCE Pythagorean communities included both male and female members. This thesis focuses on the Pythagorean women and aims to explore what reasons lie behind the prominence of women in Pythagoreanism and what roles women played in early Pythagorean societies and thought. In the first chapter, I analyse the social conditions of women in Southern Italy, where the first Pythagorean communities were founded. In the second chapter, I compare Pythagorean societies with ancient Greek political clubs and religious sects. Compared to mainland Greece, South Italian women enjoyed higher legal and socio-political status. Similarly, religious groups included female initiates, assigning them authoritative roles. Consequently, the fact that the Pythagoreans founded their communities in Croton and further afield, and that in some respects these communities resembled ancient sects helps to explain why they opened their doors to the female gender to begin with. The third chapter discusses Pythagoras’ teachings to and about women. Pythagorean doctrines did not exclusively affect the followers’ way of thinking and public activities, but also their private way of living. Thus, they also regulated key aspects of the female everyday life, such as marriage and motherhood. I argue that the Pythagorean women entered the communities as wives, mothers and daughters. Nonetheless, some of them were able to gain authority over their fellow Pythagoreans and engage in intellectual activities, thus overcoming the female traditional domestic roles. -

On the Daimonion of Socrates

SAPERE Scripta Antiquitatis Posterioris ad Ethicam REligionemque pertinentia Schriften der späteren Antike zu ethischen und religiösen Fragen Herausgegeben von Heinz-Günther Nesselrath, Reinhard Feldmeier und Rainer Hirsch-Luipold Band XVI Plutarch On the daimonion of Socrates Human liberation, divine guidance and philosophy edited by Heinz-Günther Nesselrath Introduction, Text, Translation and Interpretative Essays by Donald Russell, George Cawkwell, Werner Deuse, John Dillon, Heinz-Günther Nesselrath, Robert Parker, Christopher Pelling, Stephan Schröder Mohr Siebeck e-ISBN PDF 978-3-16-156444-4 ISBN 978-3-16-150138-8 (cloth) ISBN 987-3-16-150137-1 (paperback) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Natio- nal bibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is availableon the Internet at http:// dnb.d-nb.de. © 2010 by Mohr Siebeck Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. This book was typeset by Christoph Alexander Martsch, Serena Pirrotta and Thorsten Stolper at the SAPERE Research Institute, Göttingen, printed by Gulde- Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. SAPERE Greek and Latin texts of Later Antiquity (1st–4th centuries AD) have for a long time been overshadowed by those dating back to so-called ‘classi- cal’ times. The first four centuries of our era have, however, produced a cornucopia of works in Greek and Latin dealing with questions of philoso- phy, ethics, and religion that continue to be relevant even today.