SEP 2 5 1989 REPOSITIONING MANHATTAN OFFICE BUILDINGS by Lesley D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zoning ORDINANCE USER's MANUAL

CITY OF PROVIDENCEPROVIDENCE ZONING ORDINANCE USER'S MANUAL PRODUCED BY CAMIROS ZONING ORDINANCE USER'S MANUAL WHAT IS ZONING? The Zoning Ordinance provides a set of land use and development regulations, organized by zoning district. The Zoning Map identifies the location of the zoning districts, thereby specifying the land use and develop- ment requirements affecting each parcel of land within the City. HOW TO USE THIS MANUAL This User’s Manual is intended to provide a brief overview of the organization of the Providence Zoning Ordinance, the general purpose of the various Articles of the ordinance, and summaries of some of the key ordinance sections -- including zoning districts, uses, parking standards, site development standards, and administration. This manual is for informational purposes only. It should be used as a reference only, and not to determine official zoning regulations or for legal purposes. Please refer to the full Zoning Ordinance and Zoning Map for further information. user'’S MANUAL CONTENTS 1 ORDINANCE ORGANIZATION ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 2 ZONING DISTRICTS ................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 3 USES............................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION N 980314 ZRM Subway

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION July 20, 1998/Calendar No. 3 N 980314 ZRM IN THE MATTER OF an application submitted by the Department of City Planning, pursuant to Section 201 of the New York City Charter, to amend various sections of the Zoning Resolution of the City of New York relating to the establishment of a Special Lower Manhattan District (Article IX, Chapter 1), the elimination of the Special Greenwich Street Development District (Article VIII, Chapter 6), the elimination of the Special South Street Seaport District (Article VIII, Chapter 8), the elimination of the Special Manhattan Landing Development District (Article IX, Chapter 8), and other related sections concerning the reorganization and relocation of certain provisions relating to pedestrian circulation and subway stair relocation requirements and subway improvements. The application for the amendment of the Zoning Resolution was filed by the Department of City Planning on February 4, 1998. The proposed zoning text amendment and a related zoning map amendment would create the Special Lower Manhattan District (LMD), a new special zoning district in the area bounded by the West Street, Broadway, Murray Street, Chambers Street, Centre Street, the centerline of the Brooklyn Bridge, the East River and the Battery Park waterfront. In conjunction with the proposed action, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development is proposing to amend the Brooklyn Bridge Southeast Urban Renewal Plan (located in the existing Special Manhattan Landing District) to reflect the proposed zoning text and map amendments. The proposed zoning text amendment controls would simplify and consolidate regulations into one comprehensive set of controls for Lower Manhattan. -

CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 12. 1978~ Designation List 118 LP-0992 CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1928- 1930; architect William Van Alen. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1297, Lot 23. On March 14, 1978, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a_public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Chrysler Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 12). The item was again heard on May 9, 1978 (Item No. 3) and July 11, 1978 (Item No. 1). All hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Thirteen witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were two speakers in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters and communications supporting designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Chrysler Building, a stunning statement in the Art Deco style by architect William Van Alen, embodies the romantic essence of the New York City skyscraper. Built in 1928-30 for Walter P. Chrysler of the Chrysler Corporation, it was "dedicated to world commerce and industry."! The tallest building in the world when completed in 1930, it stood proudly on the New York skyline as a personal symbol of Walter Chrysler and the strength of his corporation. History of Construction The Chrysler Building had its beginnings in an office building project for William H. Reynolds, a real-estate developer and promoter and former New York State senator. Reynolds had acquired a long-term lease in 1921 on a parcel of property at Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street owned by the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. -

Edgar De Leon, Esq. the De Leon Firm, PLLC 26 Broadway, Suite 1700 New York, NY 10004 [email protected] (212) 747-0200

Edgar De Leon, Esq. The De Leon Firm, PLLC 26 Broadway, Suite 1700 New York, NY 10004 [email protected] (212) 747-0200 Edgar De Leon is a graduate of the Fordham University School of Law (J.D.) and Hunter College (M.S. & B.A.). He has worked as a Detective-Sergeant and an attorney for the New York City Police Department (NYPD). His assignments included investigating hate-motivated crimes for the Chief of Department and allegations of corruption and serious misconduct for the Deputy Commissioner of Internal Affairs and the Chief of Detectives. While assigned to the NYPD Legal Bureau, Mr. De Leon litigated both criminal and civil matters on behalf of the Police Department. He conducted legal research on matters concerning police litigation and initiatives and advised members of the department on matters relating to the performance of their official duties. Mr. De Leon has counseled NYPD executives and law enforcement and community-based organizations domestically and internationally concerning policy and procedure development in police-related subjects, including cultural diversity. In 2005, Mr. De Leon was part of an international team that traveled to Spain and Hungary. Working under the auspices of the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), a subdivision of the Organization for Cooperation and Strategy in Europe (OCSE), the team drafted a curriculum and implemented the first-ever training program for police officers in the European Union concerning the handling and investigation of hate crimes. In January 1999, Mr. De Leon retired from the NYPD with the rank of Sergeant S.A. -

Building Century City Lusk Seminar Paper

DRAFT: PLEASE DO NOT CIRCULATE OR CITE WITHOUT AUTHOR’S PERMISSION Creating Century City: Twentieth Century Fox and Urban Development in West Los Angeles, 1920-1975 Stephanie Frank Ph.D. Candidate, School of Policy, Planning, and Development, USC [email protected] INTRODUCTION The Fox Film Corporation, which later merged with Twentieth Century Pictures, purchased land in the undeveloped urban fringe of Los Angeles now known as West Los Angeles in 1923 in order to expand its operations from its plant in Hollywood. While there was virtually no other development in the vicinity, real estate companies, primarily the Janss Investment Company who sold Fox its land, subdivided the area surrounding the studio for single-family homes. No Sanborn Fire Insurance Map was created for the area until 1932, four years after Fox had built its studio. Other maps indicate the area remained relatively sparsely developed until the postwar period. By the time Fox decided to redevelop, and eventually to sell for redevelopment, its 280- acre property in the late 1950s, the surrounding area was completely developed. On Fox’s former backlot rose Century City, a master-planned Corbusian-inspired node of commercial, residential, and cultural activities in large-tower superblocks. This “city within a city” was a paradigm of 1960s planning that reinforced Los Angeles’s polycentric structure and remains an important economic center today. In the age of federally-funded urban renewal projects that wiped out the inner cores of cities across the country, including Los Angeles’s Bunker Hill, Century City was the largest privately-financed urban development in the country to that point in time. -

Manhattan Year BA-NY H&R Original Purchaser Sold Address(Es)

Manhattan Year BA-NY H&R Original Purchaser Sold Address(es) Location Remains UN Plaza Hotel (Park Hyatt) 1981 1 UN Plaza Manhattan N Reader's Digest 1981 28 West 23rd Street Manhattan Y NYC Dept of General Services 1981 NYC West Manhattan * Summit Hotel 1981 51 & LEX Manhattan N Schieffelin and Company 1981 2 Park Avenue Manhattan Y Ernst and Company 1981 1 Battery Park Plaza Manhattan Y Reeves Brothers, Inc. 1981 104 W 40th Street Manhattan Y Alpine Hotel 1981 NYC West Manhattan * Care 1982 660 1st Ave. Manhattan Y Brooks Brothers 1982 1120 Ave of Amer. Manhattan Y Care 1982 660 1st Ave. Manhattan Y Sanwa Bank 1982 220 Park Avenue Manhattan Y City Miday Club 1982 140 Broadway Manhattan Y Royal Business Machines 1982 Manhattan Manhattan * Billboard Publications 1982 1515 Broadway Manhattan Y U.N. Development Program 1982 1 United Nations Plaza Manhattan N Population Council 1982 1 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza Manhattan Y Park Lane Hotel 1983 36 Central Park South Manhattan Y U.S. Trust Company 1983 770 Broadway Manhattan Y Ford Foundation 1983 320 43rd Street Manhattan Y The Shoreham 1983 33 W 52nd Street Manhattan Y MacMillen & Co 1983 Manhattan Manhattan * Solomon R Gugenheim 1983 1071 5th Avenue Manhattan * Museum American Bell (ATTIS) 1983 1 Penn Plaza, 2nd Floor Manhattan Y NYC Office of Prosecution 1983 80 Center Street, 6th Floor Manhattan Y Mc Hugh, Leonard & O'Connor 1983 Manhattan Manhattan * Keene Corporation 1983 757 3rd Avenue Manhattan Y Melhado, Flynn & Assocs. 1983 530 5th Avenue Manhattan Y Argentine Consulate 1983 12 W 56th Street Manhattan Y Carol Management 1983 122 E42nd St Manhattan Y Chemical Bank 1983 277 Park Avenue, 2nd Floor Manhattan Y Merrill Lynch 1983 55 Water Street, Floors 36 & 37 Manhattan Y WNET Channel 13 1983 356 W 58th Street Manhattan Y Hotel President (Best Western) 1983 234 W 48th Street Manhattan Y First Boston Corp 1983 5 World Trade Center Manhattan Y Ruffa & Hanover, P.C. -

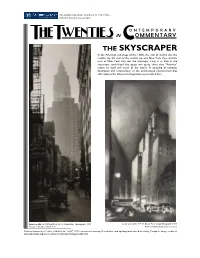

The Skyscraper of the 1920S

BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION ONTEMPORAR Y IN OMMENTARY HE WENTIES T T C * THE SKYSCRAPER In the American self-image of the 1920s, the icon of modern was the modern city, the icon of the modern city was New York City, and the icon of New York City was the skyscraper. Love it or hate it, the skyscraper symbolized the go-go and up-up drive that “America” meant to itself and much of the world. A sampling of twenties illustration and commentary on the architectural phenomenon that still captures the American imagination is presented here. Berenice Abbott, Cliff and Ferry Street, Manhattan, photograph, 1935 Louis Lozowick, 57th St. [New York City], lithograph, 1929 Museum of the City of New York Renwick Gallery/Smithsonian Institution * ® National Humanities Center, AMERICA IN CLASS , 2012: americainclass.org/. Punctuation and spelling modernized for clarity. Complete image credits at americainclass.org/sources/becomingmodern/imagecredits.htm. R. L. Duffus Robert L. Duffus was a novelist, literary critic, and essayist with New York newspapers. “The Vertical City” The New Republic One of the intangible satisfactions which a New Yorker receives as a reward July 3, 1929 for living in a most uncomfortable city arises from the monumental character of his artificial scenery. Skyscrapers are undoubtedly popular with the man of the street. He watches them with tender, if somewhat fearsome, interest from the moment the hole is dug until the last Gothic waterspout is put in place. Perhaps the nearest a New Yorker ever comes to civic pride is when he contemplates the skyline and realizes that there is and has been nothing to match it in the world. -

TM 3.1 Inventory of Affected Businesses

N E W Y O R K M E T R O P O L I T A N T R A N S P O R T A T I O N C O U N C I L D E M O G R A P H I C A N D S O C I O E C O N O M I C F O R E C A S T I N G POST SEPTEMBER 11TH IMPACTS T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. 3.1 INVENTORY OF AFFECTED BUSINESSES: THEIR CHARACTERISTICS AND AFTERMATH This study is funded by a matching grant from the Federal Highway Administration, under NYSDOT PIN PT 1949911. PRIME CONSULTANT: URBANOMICS 115 5TH AVENUE 3RD FLOOR NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10003 The preparation of this report was financed in part through funds from the Federal Highway Administration and FTA. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do no necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Federal Highway Administration, FTA, nor of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. -

2017 Annual Report Reaching Out, Making Connections, and Following Through with Treatment and Housing Services That Change Lives Is Demanding Work

2017 Annual Report Reaching out, making connections, and following through with treatment and housing services that change lives is demanding work. The men and women who work in Odyssey House’s community-based programs understand what is at stake when substance misuse or mental health problems are not treated. While they see the pain of addiction and the tragedy of lives cut short, they also see hope in recovery and lives saved. Helping New Yorkers overcome life challenges keeps us going and keeps us on the front lines. In this report, read about how volunteer recovery coach Jesse Westbrook and his colleagues at the Odyssey House Recovery Center are reaching out and connecting with families, adolescents, and seniors in their South Bronx community. Building community and saving lives IT IS THE MISSION OF ODYSSEY HOUSE: To provide comprehensive and innovative services to the broadest range of metro New York’s population who: • Abuse drugs • Abuse alcohol • Suffer from mental illness To provide high quality, holistic treatment impacting all major life spheres: psychological, physical, social, family, educational and spiritual. To support personal rehabilitation, renewal and family restoration. In all of its activities, Odyssey House undertakes to act as a responsible employer and member of the community, and manage the assets of the organization in a professional manner. 1 WHAT YOU CANNOT DO ALONE, WE CAN DO TOGETHER Treatment and recovery services are at the heart of treatment programs. However, treatment is of what we provide at Odyssey House. Supporting just the beginning of what it takes to save a New Yorkers and their families as they overcome life. -

26 Broadway Educational Campus

The landmarked building in Lower Manhattan gets a second life as a 26 Broadway school thanks to its steel structure and an innovative adaptive reuse plan. Educational FOR THE PAST SEVERAL YEARS, the landmarked transformed from the oil giant’s Carrère and Hast- ings-designed headquarters into a lively academic Campus complex for secondary students in Lower Manhat- tan. The third academic institution to be located in the building, it occupies 104,000 square feet of and adds nearly 700 high school seats to what SCA complex, which also includes the Urban Assembly - Ciardullo Associates, who has worked extensively this longstanding relationship is why Ciardullo was allowed to have a bit of fun with the campus, trans- forming an underused mechanical courtyard into a dramatic double-height, steel-framed gymnasium. most of the building’s existing structure is steel, for a gymnasium into the columns already in place. literally put the beams anywhere within the steel structure. If you had a concrete structure, you’d have a problem analyzing it structurally because you don’t know what reinforcing steel is in the concrete frame. You would have to drill into the concrete to the building, we could create a large space that could function as a gym and we could bring in light through a skylight,” says Ciardullo. Though the idea of giving Manhattan students an indoor gym was a novel one, the execution of it proved relatively window openings two stories above street level, the open courtyard space. There, the beams were welded at one end to existing steel columns on the portion of the building built in 1921. -

J. & W. Seligman & Company Building

Landmarks Preservation Commission February 13, 1996, Designation List 271 LP-1943 J. & W. SELIGMAN & COMPANY BUILDING (later LEHMAN BROTHERS BUILDING; now Banca Commerciale Italiana Building), 1 William Street (aka 1-9 William Street, 1-7 South William Street, and 63-67 Stone Street), Borough of Manhattan. Built 1906-07; Francis H. Kimball and Julian C. Levi, architects; George A. Fuller Co., builders; South William Street facade alteration 1929, Harry R. Allen, architect; addition 1982-86, Gino Valle, architect. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 29, Lot 36. On December 12, 1995, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the J. & W. Seligman & Company Building (later Lehman Brothers Building; now Banca Commerciale Italiana Building) and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing was continued to January 30, 1996 (Item No. 4). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Nine witnesses spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger, Council Member Kathryn Freed, Municipal Art Society, New York Landmarks Conservancy, Historic Districts Council, and New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. In addition, the Commission has received a resolution from Community Board 1 in support of designation. Summary The rusticated, richly sculptural, neo-Renaissance style J. & W. Seligman & Company Building, designed by Francis Hatch Kimball in association with Julian C. Levi and built in 1906-07 by the George A. Fuller Co. , is located at the intersection of William and South William Streets, two blocks off Wall Street. -

Skyscrapers and District Heating, an Inter-Related History 1876-1933

Skyscrapers and District Heating, an inter-related History 1876-1933. Introduction: The aim of this article is to examine the relationship between a new urban and architectural form, the skyscraper, and an equally new urban infrastructure, district heating, both of witch were born in the north-east United States during the late nineteenth century and then developed in tandem through the 1920s and 1930s. These developments will then be compared with those in Europe, where the context was comparatively conservative as regards such innovations, which virtually never occurred together there. I will argue that, the finest example in Europe of skyscrapers and district heating planned together, at Villeurbanne near Lyons, is shown to be the direct consequence of American influence. Whilst central heating had appeared in the United Kingdom in the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries, district heating, which developed the same concept at an urban scale, was realized in Lockport (on the Erie Canal, in New York State) in the 1880s. In United States were born the two important scientists in the fields of heating and energy, Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) and Benjamin Thompson Rumford (1753-1814). Standard radiators and boilers - heating surfaces which could be connected to central or district heating - were also first patented in the United States in the late 1850s.1 A district heating system produces energy in a boiler plant - steam or high-pressure hot water - with pumps delivering the heated fluid to distant buildings, sometimes a few kilometers away. Heat is therefore used just as in other urban networks, such as those for gas and electricity.