Whistleblowing Speech and the First Amendment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extr@ English Programme Summaries

extr@ English Programme Summaries Table of Contents Episode 1: Hector’s Arrival ............................................................................................................... 2 Episode 2: Hector Goes Shopping................................................................................................... 2 Episode 3: Hector Has a Date.......................................................................................................... 2 Episode 4: Hector Looks for a Job ................................................................................................... 2 Episode 5: A Star Is Born ................................................................................................................. 3 Episode 6: Bridget Wins the Lottery................................................................................................. 3 Episode 7: The Twin......................................................................................................................... 3 Episode 8: The Landlady’s Cousin................................................................................................... 3 Episode 9: Jobs for the Boys............................................................................................................ 4 Episode 10: Annie’s Protest ............................................................................................................. 4 Episode 11: Holiday Time ............................................................................................................... -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Whistleblower Thesis.Pdf (1.788Mb)

ABSTRACT Would You Blow-the-Whistle on a Friend? Analysis of the Significance of Relationships on Whistleblower Intentions Amy Miller Director: Kathy Hurtt, Ph.D. Whistleblowing is an essential tool in exposing wrongdoings and ending corruption, however it can be an arduous and unforgiving task that few are willing to accept. Individuals that do decide to blow-the-whistle are often subject to retaliation, loss of employment, and defamation of character. Despite the costs associated with whistleblowing, there are individuals who are willing to come forward about these illegal, unruly, or unethical, acts. This study analyzes how a person‘s relationship with a wrongdoer affects whether he or she reports the wrongdoer‘s misconduct. In this study over 360 undergraduate and graduate business students were asked if they would report a wrongdoing based on a series of scenarios. The scenarios incorporated a variety of situations that could occur either at a university or a corporation. The data showed there was a significant difference in the responses from students when the wrongdoer was a stranger and when the wrongdoer had a closer relationship with the potential whistleblower. The data also exhibited that when a wrongdoer holds a superior position to the potential whistleblower, the potential whistleblower would be affected by the wrongdoer‘s superior position unless the wrongdoing committed is extremely severe. This study shows that the whistleblower‘s relationship with the wrongdoer does affect his or her intent to blow-the-whistle. This research is valuable in understanding the factors that drive the whistleblower‘s intent to report misconduct. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS Dr. -

Power and Influence: Getting It - Keeping It

Power and Influence: Getting It - Keeping It Course No: K03-001 Credit: 3 PDH Richard Grimes, MPA, CPT Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] Power and Influence: Getting It ‐Keeping It Richard Grimes Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Learning Outcomes ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Intended Audience ........................................................................................................................................ 4 A View of Power ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Compliance vs. Commitment .................................................................................................................... 6 The Changing Workplace ............................................................................................................................ 10 Sources of Personal Power within the Organization .................................................................................. 11 Expertise............................................................................................................................................. -

Praise for the Corporate Whistleblower's Survival Guide

Praise for The Corporate Whistleblower’s Survival Guide “Blowing the whistle is a life-altering experience. Taking the fi rst step is the hardest, knowing that you can never turn back. Harder yet is not taking the step and allowing the consequences of not blowing the whistle to continue, knowing you could have stopped them. Your life will be forever changed; friends and family will question your ac- tions if not your sanity, your peers will shun you, every relationship you treasure will be strained to the breaking point. This handbook is required reading for anyone considering blowing the whistle.” —Richard and Donna Parks, Three Mile Island cleanup whistleblower and wife “The Corporate Whistleblower’s Survival Guide will be an immense help! For while there are no one-size-fi ts-all ‘right answers,’ the au- thors have effectively translated their decades of actual experience, insights, and resources in this fi eld onto paper. A realistic framework will now exist to help people confronting such diffi cult situations.” —Coleen Rowley, FBI 9/11 whistleblower and a 2002 Time Person of the Year “Lays out exactly what potential corporate whistleblowers must know to help improve their chances of both surviving whistleblowing and stopping the misconduct they set out to expose. My only hope is that we can help spread the word so that all potential corporate whistle- blowers read this book before they take their fi rst steps down that lonely road.” —Danielle Brian, Executive Director, Project on Government Oversight “As commissioner, I relied on whistleblowers like Jeffrey Wigand to learn the inside story about the deceptive practices of the tobacco industry. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION In 1992, the Commission conducted a two-day To date, Leonetti has testified in eight federal tri- public hearing on the control of bars by organized crime als, plus three re-trials, and three state trials in prosecu- and issued a report. The Commission identified several tions of the Pittsburgh La Cosa Nostra and the Patriarca, such establishments and the organized crime members Genovese, Gambino/Gotti, Lucchese, Colombo and and associates holding interests in them. Most of the Bruno/Stanfa Families. His testimony has led to the owners of record and all of the organized crime figures convictions of more than 15 made members and 23 as- invoked their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimi- sociates, including Nicholas Bianco, who was elevated nation at the hearing and refused to answer questions. from underboss to boss of the Patriarca Family of New The hearing and report featured the testimony of a former England following his indictment and prior to his convic- made member and a former associate of the Southeast- tion, together with virtually the entire hierarchy of the ern Pennsylvania-South Jersey Family of La Cosa Patriarca Family; Charles “Chucky” Porter, underboss Nostra. In striking testimony, former captain Thomas of the Pittsburgh La Cosa Nostra; Venero “Benny Eggs” “Tommy Del” DelGiorno and a former associate, whose Mangano, consigliere of the Genovese/Gigante Family identity had to be concealed for his protection, explained in New York; Benedetto Aloi, consigliere of the why organized crime gravitates toward liquor-licensed Colombo Family in New York; Santo Idone, a captain establishments — from use of the business to launder of the Bruno/Scarfo Family, and acting captain Michael money to use of the premises as a safe haven to meet Taccetta and soldiers Anthony “Tumac” Accetturo,2 and conduct illegal business, including the plotting of Martin Taccetta and Thomas Ricciardi, all of the New murders. -

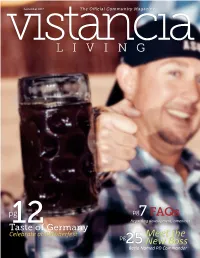

Meet the New Boss

September 2017 pg pg7 FAQs Regarding development, amenities Taste12 of Germany Celebrate at Oktoberfest Meet the pg25 New Boss Bezio Named PD Commander SELLING HOMES SINCE 2005 IN: Blackstone, Trilogy & Vistancia Village NOW IS THE PERFECT TIME TO SELL LAKE PLEASANT REAL ESTATE JAY PATEL - Owner / Agent SOLD BY Jay 31099 N 137th Ave 28349 N 128th Dr 29228 N 122nd Dr 30702 N 125th Dr 12072 W Desert Mirage Dr VISTANCIA VILLAGE TRILOGY VISTANCIA VILLAGE VISTANCIA VILLAGE BLACKSTONE 28827 N 127th Ave 12795 W Via Caballo Blanco 30233 N 124th Dr 12721 W Crestvale Dr 12597 W Blackstone Ln TRILOGY BLACKSTONE VISTANCIA VILLAGE TRILOGY VISTANCIA VILLAGE To SELL Your Home Fast, Call or Text Jay at 623.451.0443 Jay Patel - Owner / Agent Lake Pleasant Real Estate Juris Doctor / Attorney-at-Law Direct: 623.451.0443 [email protected] www.KeyToAzHomes.com 28451 N Vistancia Blvd., Ste D-103, Peoria, AZ 85383 Not intended to solicit property already for sale. The KEY to your Real Estate needs! SELLING HOMES SINCE 2005 IN: Blackstone, Trilogy & Vistancia Village Jay’s NOW IS THE PERFECT TIME TO SELL BLACKSTONE FORMER MODEL! COMING SOON! PREMIUM LOT! 12406 W Morning Vista Ln 12080 W Desert Mirage Dr 29502 N 124th Ln 5 BR, 4.5 BA, 4353 SF 2 BR, 2 BA, 2 CG, 1920 SF 3 BR + DEN, 2 BA, 2 CG, POOL, 2063 SF www.12406WMorningVistaLane.utour.me www.12080WDesertMirageDrive.utour.me www.29502N124thLane.utour.me LAKE PLEASANT REAL ESTATE JAY PATEL - Owner / Agent SOLD BY Jay PRIVATE YARD! MODEL-LIKE+VIEWS! 2 MASTER BEDROOMS! 30767 N 137th Ave 32364 N 129th Dr 12357 W Maya Way 4 BR, 2.5 BA, 2 CG, POOL, 2537 SF 4 BR, 3.5 BA, 2 CG, POOL, 3121 SF 2 BR + DEN, 2 BA, 2 CG, 1635 SF www.30767N137thAvenue.utour.me www.32364N129thDrive.utour.me www.12357WMayaWay.utour.me 5-STAR AGENT 31099 N 137th Ave 28349 N 128th Dr 29228 N 122nd Dr 30702 N 125th Dr 12072 W Desert Mirage Dr VISTANCIA VILLAGE TRILOGY VISTANCIA VILLAGE VISTANCIA VILLAGE BLACKSTONE SOLD OUR HOME FAST & AT A PRICE WE WANTED! - “Jay sold our home quickly and for the price we wanted. -

Think Christian – a Theology of the Office

A Theology of the office 8½ x 11 in 20 lb Text 21.5 x 27.9 cm 75 GSM Bright White 92 Brightness 500 Sheets 30% Post-Consumer Recycled Fiber RFM 20190610 TC TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction by JOSH LARSEN 1 The Awkward Promise of The Office by JR. FORASTEROS 3 Can Anything Good Come Out of Scranton? by BETHANY KEELEY-JONKER 6 St. Bernard and the God of Second Chances by AARIK DANIELSEN 8 The Irrepressible Joy of Kelly Kapoor by KATHRYN FREEMAN 11 Let Scott’s Tots Come Unto Me by JOE GEORGE 13 The Office is Us by JOSH HERRING 16 Editors JOSH LARSEN & ROBIN BASSELIN Design & Layout SCHUYLER ROOZEBOOM Introduction by JOSH LARSEN You know the look. Someone (usually Michael) says something cringeworthy and someone else (most often Jim) glances at the camera, slightly widens his eyes, and imperceptibly grimaces. That was weird, his face says, for all of us. That look was the central gag of The Office, NBC’s reimagining of a British television sitcom about life amidst corporate inanity. The joke never got old over nine seasons. Part of the show’s conceit is that a documentary camera crew is on hand capturing all this footage, allowing the characters to break the fourth wall with a running, reaction-shot commentary. A textbook example can be found in “Koi Pond,” from Season 6, when Jim (John Krasinski) finds the camera after Michael (Steve Carell) makes yet another inappropriate analogy during corporate sensitivity training. Don’t even try to count the number of times throughout The Office that eyebrows are alarmingly raised. -

Talking to Strangers: the Use of a Cameraman in the Office and What

Running Head: TALKING TO STRANGERS 1 Talking to Strangers The Use of a Cameraman in The Office and What It Reveals about Communication Sarah Stockslager A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Fall 2010 TALKING TO STRANGERS 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Lynnda S. Beavers, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Robert Lyster, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ James A. Borland, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date TALKING TO STRANGERS 3 Abstract In the television mock-documentary The Office, co-workers Jim and Pam tell the cameraman they are dating before they tell their fellow co-workers in the office. The cameraman sees them getting engaged before anyone in the office has a clue. Even the news of their pregnancy is witnessed first by the camera crew. Jim and Pam’s boss, Michael, and other employees, such as Dwight, Angela and others, also share this trend of self-disclosure to the cameraman. They reveal secrets and embarrassing stories to the cameraman, showing a private side of themselves that most of their co-workers never see. First the term “mock-documentary” is explained before specifically discussing the The Office. Next the terms and theories from scholarly sources that relate the topic of self-disclosure to strangers are reviewed. Consequential strangers, weak ties, the stranger- on-a-train phenomenon, and para-social interaction are studied in relation to the development of a new listening stranger theory. -

Owning the Olympics

Owning the Olympics Owning the Olympics Narratives of the New China Monroe E. Price and Daniel Dayan, Editors THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS and THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN LIBRARY Ann Arbor Copyright © by Monroe E. Price and Daniel Dayan 2008 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2011 2010 2009 2008 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN-13: 978-0-472-07032-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-472-07032-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-472-05032-1 (paper : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-472-05032-X (paper : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-472-02450-6 (electronic) Contents Introduction Monroe E. Price 1 I. De‹ning Beijing 2008: Whose World, What Dream? “One World, Different Dreams”: The Contest to De‹ne the Beijing Olympics Jacques deLisle 17 Olympic Values, Beijing’s Olympic Games, and the Universal Market Alan Tomlinson 67 On Seizing the Olympic Platform Monroe E. Price 86 II. Precedents and Perspectives The Public Diplomacy of the Modern Olympic Games and China’s Soft Power Strategy Nicholas J. Cull 117 “A Very Natural Choice”: The Construction of Beijing as an Olympic City during the Bid Period Heidi Østbø Haugen 145 Dreams and Nightmares: History and U.S. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transnational Television

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transnational Television, International Anxieties: Examining Cross-Cultural Representations of Workplace Power Struggles and Tensions over Hierarchical Standing in The Office A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology by Jessica Julia McGill Peters 2012 © Copyright by Jessica Julia McGill Peters 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Transnational Television, International Anxieties: Examining Cross-Cultural Representations of Workplace Power Struggles and Tensions over Hierarchical Standing in The Office by Jessica Julia McGill Peters Master of Arts in Anthropology University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Sherry B. Ortner, Chair Though often considered a homogenizing force, global media has been undergoing a process of re-examination as findings reveal the ways in which transplanted media, such as transnational television programs, are recontextualized or transformed through local interpretations, thereby assuming more interstitial forms. This study furthers such re-evaluations, and contributes to broader investigations into the nature of globalization as concurrently homogenizing and differentiating, through its examination of culturally-specific and cross- culturally shared representations of workplace power struggles and tensions over hierarchical standing in transnational adaptations of the television program The Office. ii A cross-cultural analysis of the televisual texts of the original British Office and its American remake -

Preparing for the Arrival of a New Leader

LEADERSHIP TIPS | www.public-sector.org Preparing for the Arrival of Patty Guard a New Leader Board Member, Public Sector Consortium Former Deputy Director of Special Education Programs, US Dept. of Education Email: [email protected] Build trust and credibility with the new leader Contact the new leader to introduce yourself, to say congratulations and that you are looking forward to working with them. Share that it is your job to help them be successful and that you will begin preparing for their arrival. Brief them on what you will do to orient them, and tell them that you are anxious to learn what their priorities will be and to work with the organization to help implement them. Check for immediate needs or expectations they may have. Advise them that they will want to be prepared to make a timely announcement about their priorities and values. Offer to send speeches or other public documents that summarize the vision of the senior leader in the organization. This will help them to think about their priorities and how they will align with that vision. Be selective when considering which documents to send to avoid information overload, and be sure to send only public information since they are not yet an employee of the agency. Tell them to feel free to contact you if there is anything you can do to assist prior to their arrival. View this contact as the first step in establishing a positive working relationship with the new leader. Prepare for orientation Preparing the orientation includes developing one or two page briefing papers tailored to the new leader’s particular background and expertise.