Cox's Road Dreaming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Kings Tableland Wentworth Falls

ENCLOSURE REPORT ON KINGS TABLELAND WENTWORTH FALLS Compiled by City Planning Branch November 2006 File:C07886 City Planning Branch - November 2006 Page 1 of 33 File: C07886 1. Background At the 21 March 2006 Council Meeting a Notice of Motion was put before the Council on the Kings Tableland Plateau, Wentworth Falls. As a result the Council resolved: That a report be submitted to Council on the Kings Tableland Plateau, Wentworth Falls, with particular reference to the Queen Victoria Hospital site, such report to address the following: • adequacy of zoning and other planning controls; • preservation of environmental and cultural values in this unique area • protection of the surrounding world heritage areas; • protection of nationally endangered and regionally significant Blue Mountains swamps and the identification of adequate buffer areas; • protection of significant communities and species (both flora and fauna); • protection of indigenous sites and values; • assessment of the heritage values of the Queen Victoria buildings; • assessment of bushfire history and the risk to existing and potential future development; and • consideration of suitable size and location of any future development on Kings Tableland. (Minute No. 517, 21/03/06) This Report (Report on Kings Tableland, Wentworth Falls) has been prepared in response to the above Council Resolution. The Report is structured into ten parts: 1. Background 2. Introduction to the Kings Tableland 3. Values of Kings Tableland including environmental, cultural, social and economic 4. Current land use in the Kings Tableland 5. Risks, including bushfire 6. Current threats to the values of Kings Tableland 7. Future development and the adequacy of current planning controls 8. -

CENTRAL BLUE MOUNTAINS ROTARY CLUB INC. “Service Above Self” District 9685, Australia

CENTRAL BLUE MOUNTAINS ROTARY CLUB INC. “Service above Self” District 9685, Australia A SHORT PRECIS (Who, What and Where !) WHO AND WHAT ARE WE ? Central Blue Mountains Rotary is one of five rotary Clubs located in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. We are innovative and progressive... we are a “Can Do” group of Rotarians, proud of what we achieve, and we have fun doing it. We are a club of 43 members (40 active and 3 honorary). In Rotary, women are the fastest growing membership segment and we are proud to say that 25% of our members are women. Our club meets weekly on Wednesday at the “Grandview Hotel”, 174 Great Western Highway, Wentworth Falls at 6.30pm. Our meeting format is relaxed and we have great guest speakers. Sure, we sell raffle tickets and we cook and sell sausage sandwiches just like other Rotary clubs - we have a big catering van to do this....It’s great! But our community service activities are the heart of what we do, ranging from local projects to helping communities overseas. We have a website http://centralbluerotary.org/ Perhaps our greatest challenge at present; We have been awarded a RAWCS Project Fund to raise A$280,000 to construct a new, enlarged Astha Home for Girls in Kathmandu, Nepal. The massive earthquake that struck Nepal in 2015 caused much upheaval to the lives of many people and destroyed or damaged many homes and buildings, especially in the hills and valleys outside of Kathmandu. The Astha Home for Girls is currently located in rented premises but the owner wants it back for his family members who lost their home in the earthquake. -

Hyde Park Management Plan

Hyde Park Reserve Hartley Plan of Management April 2008 Prepared by Lithgow City Council HYDE PARK RESERVE HARTLEY PLAN OF MANAGEMENT Hyde Park Reserve Plan of Management Prepared by March 2008 Acknowledgements Staff of the Community and Culture Division, Community and Corporate Department of Lithgow City Council prepared this plan of management with financial assistance from the NSW Department of Lands. Valuable information and comments were provided by: NSW Department of Lands Wiradjuri Council of Elders Gundungurra Tribal Council members of the Wiradjuri & Gundungurra communities members of the local community and neighbours to the Reserve Lithgow Oberon Landcare Association Central Tablelands Rural Lands Protection Board Lithgow Rural Fire Service Upper Macquarie County Council members of the Hartley District Progress Association Helen Drewe for valuable input on the flora of Hyde Park Reserve Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Canberra Tracy Williams - for valuable input on Reserve issues & uses Department of Environment & Conservation (DECC) NW Branch Dave Noble NPWS (DECC) Blackheath DECC Heritage Unit Sydney Photographs T. Kidd This Hyde Park Plan of Management incorporates a draft Plan of Management prepared in April 2003. Lithgow City Council April 2008 2 HYDE PARK RESERVE HARTLEY PLAN OF MANAGEMENT FOREWORD 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 PART 1 – INTRODUCTION 7 1.0 INTRODUCTION 8 1.1 PURPOSE OF A PLAN OF MANAGEMENT 8 1.2 LAND TO WHICH THE PLAN OF MANAGEMENT APPLIES 9 1.3 GENERAL RESERVE -

TRANSFERS 1 January 2021 - 31 March 2022

TRANSFERS 1 January 2021 - 31 March 2022 Emirates One&Only Wolgan Valley is located approximately 190 kilometres or a three-hour drive from Sydney in the World Heritage-listed Greater Blue Mountains region. Guests can arrive to the resort in style via a private chauffeur car service or embark on an unforgettable aerial journey via helicopter over Sydney, with stunning vistas as you cross the Greater Blue Mountains. PRIVATE TRANSFERS BY CAR Evoke and Unity Executive Services offer private transfers with flexible Sydney CBD or airport meeting points and departure times. Evoke Via Katoomba (Direct to Resort) Head towards the mountains and enjoy a quick stop at Hydro Majestic Pavilion Cafe with views over the Megalong Valley. The journey will then continue through the quaint township of Lithgow before entering Wolgan Valley. Via Katoomba (Scenic Tour to Resort) A relaxed transfer with a leisurely stop in the historic township of Katoomba. Enjoy a leisurely self-guided walk to the view the Three Sisters and experience the Jamison Valley. Take an excursion on the panoramic scenic railway at Scenic World (tickets additional). Transfer option includes two-hour stop. Unity Executive Services Via Bells Line of Road (Direct to Resort) Depart Sydney and connect with the picturesque Bells Line of Road to the northwest of Sydney. Travel through the mountains and pass quaint villages, apple orchards, as well as the townships of Bell and Lithgow, before entering Wolgan Valley. Via Katoomba (Scenic Stop to Resort) This sightseeing journey begins as you head towards the mountains. Travelling to the township of Katoomba, stop at Cafe 88 to view the famous Three Sisters rock formation. -

"THE GREAT 'WESTEBN EOAD" Illustrated. by Frank Walker.FRAHS

"THE GREAT 'WESTEBN EOAD" Illustrated. By Frank Walker.F.R.A.H.S MAMULMft VFl A WvMAfclVA/tJt* . * m ■ f l k i n £ f g £ 1 J k k JJC " l l K tfZZ) G uild,n g j XoCKt AHEA . &Y0AtMY. * ' e x . l i e.k «5 — »Ti^ k W^ukeK.^-* crt^rjWoofi. f^jw. ^ . ' --T-* "TTT" CiREAT WESTERN BOAD” Illustrated. —— By Fra^fr talker-F.R.A.H,S Ic&Sc&M The Great Western Hoad. I ■ -— ' "..................... ----------- FORE W ORE ----------------- The Ji5th April,x815,was a"red-letter day" in the history of Hew South Wales,as it signalled the throwing open of the newly“discovered western country to settlement,and the opening of the new road,which was completed by William uox,and his small gang of labourers in January,of the same year. The discovery of a passage across those hither to unassailaole mountains by ulaxland,Lawson and wentworth,after repeated failures by no less than thirteen other expeditions;the extended discoveries beyond Blaxland s furthest point by ueorge William Evans,and the subsequent construction of the road,follow -ed each other in rapid sequence,and proud indeed was i.acquarie, now that his long cherished hopes and ambitions promised to be realised,and a vast,and hitherto unknown region,added to the limited area which for twenty-five years represented the English settlement in Australia. Separated as we are by more than a century of time it is difficult to realise what this sudden expansion meant to the tfeen colony,cribbed,cabbined and confined as it had been by these mysterious mountains,which had guarded their secret so well, '^-'he dread spectre of famine had once again loomed up on the horizon before alaxland s successful expedition had ueen carried out,and the starving stock required newer and fresher pastures if they were to survive. -

The Tablelands Bushwalking Club

The Tablelands Bushwalking Club Newsletter – April 2018 The Tablelands Bushwalking Club Five National Parks to Put on Your Radar P O Box 1020 Great Walks enews 19 March 2108 Tolga 4882 www.tablelandsbushwalking.org Australia has one of the largest and greatest national park systems in the world, covering [email protected] almost four per cent of the country's land mass (or 25 million hectares). With over 500 President: Sally McPhee - 4096 6026 national parks on offer you'd imagine there might be few that don't appear on the public's Vice President: Patricia Veivers - 4095 4642 radar but are worth exploring, so check out these 5 unsung heroes. Vice President: Tony Sanders – 0438 505 394 Yuraygir NP, NSW Treasurer: Christine Chambers – 0407 344 456 Located less than an hour's drive north of Secretary: Travis Teske - 4056 1761 Coffs Harbour, Yuraygir is known for having some of the best surfing on the east coast. Activity Officers: Birdwatchers will find plenty in the late winter Philip Murray – 0456 995 458 and early spring between the heath and the Marilyn Czarnecki – 0409 066 076 forest areas. Health & Safety Officer: The 10km Angourie walk is three hours return Morris Mitchell – 4092 2773 along the northern edge of the park, giving access to a fragile coastline of rugged beauty. Newsletter Editor: Travis Teske - 4056 1761 Dolphins often can be seen offshore and in [email protected] winter you might spot whales. Shelley Beach is a great halfway point to stop for lunch or If a Walking Trip is Delayed – What Your camp. -

Journal 3; 2012

BLUEHISTORY MOUNTAINS JOURNAL Blue Mountains Association of Cultural Heritage Organisations Issue 3 October 2012 I II Blue Mountains History Journal Editor Dr Peter Rickwood Editorial Board Associate Professor R. Ian Jack Mr John Leary OAM Associate Professor Carol Liston Professor Barrie Reynolds Dr Peter Stanbury OAM Web Preparation Mr Peter Hughes The Blue Mountains History Journal is published online under the auspices of BMACHO (Blue Moun- tains Association of Cultural Heritage Organisations Inc.). It contains refereed, and fully referenced articles on the human history and related subjects of the Greater Blue Mountains and neighbouring areas. Anyone may submit an article which is intermediate in size be- tween a Newsletter contribution and a book chapter. Hard copies of all issues, and hence of all published articles, are archived in the National Library of Austral- ia, the State Library of NSW, the Royal Australian Historical Society, the Springwood Library, the Lithgow Regional Library and the Blue Mountains Historical Society,Wentworth Falls. III IV Blue Mountains Historical Journal 3; 2012 http://www.bluemountainsheritage.com.au/journal.html (A publication of the BLUE MOUNTAINS ASSOCIATION OF CULTURAL HERITAGE ORGANISATIONS INCORPORATED) ABN 53 994 839 952 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ISSUE No. 3 SEPTEMBER 2012 ISSN 1838-5036 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– CONTENTS Editorial Peter Rickwood V The Blue Mountains: where are they? Andy Macqueen 1 The Mystery of Linden’s Lonely Gravestone: who was John Donohoe? John Low, OAM 26 Forensic history: Professor Childe’s Death near Govetts Leap - revisited. Peter Rickwood 35 EDITORIAL Issue 3 of The Blue Mountains History Journal differs from its predecessors in that it has three papers rather than four. -

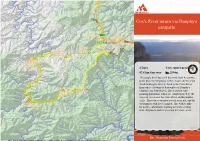

Cox's River Return Via Dunphy's Campsite

Cox's River return via Dunphy's campsite 3 Days Very experienced only6 47.8 km One way 2390m This tough, three day walk descends from Katoomba to the peaceful Megalong Valley. It uses the Six Foot Track to navigate its way down to the Cox's River from where it returns to Katoomba via Dunphy's campsite and Narrowneck. The walk has some stunning panoramas which are complemented by the close-up views over the Cox's River and Katoomba cliffs. These notes are now several years old, and the environment will have changed, This walk is only for people comfortable walking off track, dealing with cliff passes and steep terrain in remote areas. 1071m 203m Blue Mountains National Park Maps, text & images are copyright wildwalks.com | Thanks to OSM, NASA and others for data used to generate some map layers. Free Beacon Hire Before You walk Grade A Personal Locating Beacon (PLB) is a hand-held device that, when Bushwalking is fun and a wonderful way to enjoy our natural places. This walk has been graded using the AS 2156.1-2001. The overall triggered, sends a message to the emergency services with your Sometimes things go bad, with a bit of planning you can increase grade of the walk is dertermined by the highest classification along location. The emergency services staff can then look at your trip your chance of having an ejoyable and safer walk. the whole track. intention forms and decide how best to help you. In the Blue Before setting off on your walk check Mountains, you can borrow these for no charge, just complete this Trip intention form, and a borrowing form. -

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration Along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History That Refl Ects National Trends

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History that Refl ects National Trends DOUG BENSON Honorary Research Associate, National Herbarium of New South Wales, Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Sydney NSW 2000, AUSTRALIA. [email protected] Published on 10 April 2019 at https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/LIN/index Benson, D. (2019). Two centuries of botanical exploration along the Botanists Way, northern Blue Mountains,N.S.W: a regional botanical history that refl ects national trends. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 141, 1-24. The Botanists Way is a promotional concept developed by the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden at Mt Tomah for interpretation displays associated with the adjacent Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (GBMWHA). It is based on 19th century botanical exploration of areas between Kurrajong and Bell, northwest of Sydney, generally associated with Bells Line of Road, and focussed particularly on the botanists George Caley and Allan Cunningham and their connections with Mt Tomah. Based on a broader assessment of the area’s botanical history, the concept is here expanded to cover the route from Richmond to Lithgow (about 80 km) including both Bells Line of Road and Chifl ey Road, and extending north to the Newnes Plateau. The historical attraction of botanists and collectors to the area is explored chronologically from 1804 up to the present, and themes suitable for visitor education are recognised. Though the Botanists Way is focused on a relatively limited geographic area, the general sequence of scientifi c activities described - initial exploratory collecting; 19th century Gentlemen Naturalists (and lady illustrators); learned societies and publications; 20th century publicly-supported research institutions and the beginnings of ecology, and since the 1960s, professional conservation research and management - were also happening nationally elsewhere. -

English Language Company, Sydney

ITINERARY Regarded as Australia’s most outstanding cave system, Jenolan Caves is among the finest and oldest cave systems in the world. The Jenolan cave network is enormous with the total length of cave passage estimated at over 40kms! Jenolan Caves Wild nature and wild animals Highlights/Inclusions $119 The Three Sisters The famous Three Sisters rock formation is one of the most iconic images in Australia. The views overlooking the Jamison Valley are incredible and as well as getting that classic photo, you'll hear the stories of the local Aboriginal legends. Govetts Leap One of the most awesome lookouts in the Blue Mountains with views looking into the Grose Valley, wilderness as far as the eye can see and the magical Bridal Veil Falls. Jenolan Caves You'll feel you've travelled back in time as you pass down a winding mountain road deep into an isolated valley of Kanangra – Boyd National Park, drive through the cave entrance and arrive at the enchanting hideaway village of Jenolan. Cave tour Regarded as Australia’s most outstanding cave system, Jenolan Caves is among the finest and oldest cave systems in the world. A specialised guide will take you underground for an amazing cave tour experience! Wild kangaroos and wallabies We travel to the end of a dirt road through the forest to a clearing where wild kangaroos and wallabies graze quietly within camera range. Photo opportunities like this are rare so we need to be as quiet as possible. Depart: Sydney 7.20am KX/ 7.35am YHA/ 7.55am CQ Return: Sydney 6.30pm For bookings, information and additional trip departures please contact your Activity Coordinator. -

Australian Studies Journal 32/2018

https://doi.org/10.35515/zfa/asj.32/2018.04 Cassandra Pybus University of Sydney Revolution, Rum and Marronage The Pernicious American Spirit at Port Jackson I find it no small irony to write about enlightenment power at Port Jackson. As a his- torian who is interested in the nitty gritty of ordinary lived experience in the penal colony, I have found nothing at Port Jackson that looks enlightened. White Australians would dearly like to have a lofty foundation story about how the nation sprang from enlightenment ideals, such as the American have invented for themselves, which is why Australians don’t look too closely at the circumstances in which our nation was born in a godforsaken place at the end of the world that was constituted almost entirely by the brutalised and the brutalising. This narrative is not likely to be found in any popular account of the European settlement of Aus- tralia as there is no enlightened power to be found in this tale. Looming over the narrative is the omnipresent, and utterly venal, New South Wales Corps, who ran the colony for their own personal profit for nearly two decades. My narrative begins on 14 February 1797, when a convict named John Winbow was footslogging through virgin bush about five miles west of Port Jackson in search of a fugitive convict with the singe name of Caesar. Having reached a narrow rock shelter in a sandstone ridge he knew he had found his quarry then and settled down to wait for the outlaw to show himself. Having once made his living as a highway- man, it went against the grain for Winbow to be hunting a fellow outlaw, but the lavish reward of five gallons of undiluted rum was too enticing for scruples.1 Rum was the local currency at Port Jackson and five gallons represented a small fortune. -

Australia Visited and Revisited

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us.