Evidence in Civil Law – Lithuania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Protection of Human Rights in the Decisions of the Italian Supreme Court of Cassation

St. John's Law Review Volume 70 Number 1 Volume 70, Winter 1996, Number 1 Article 9 The Protection of Human Rights in the Decisions of the Italian Supreme Court of Cassation Hon. Antonio Brancaccio Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE DECISIONS OF THE ITALIAN SUPREME COURT OF CASSATION HON. ANTONIO BRANCACCIO" INTRODUCTION Over the last few decades, countries of common law and civil law traditions have undergone a process which has brought them closer together. This process can be traced back to the common conviction that law does not consist merely of complex, abstract norms, but rather of decisions made in applying these norms. In other words, it is the decisions of the courts which constitute the law in force. Thus, any understanding of the protection of hu- man rights requires reference to the decisions of judges who are called upon to decide cases in which this protection is challenged at both the international and national levels. At the national level, the decisions of supreme courts take on particular importance. I would like to refer briefly to the deci- sions of the Italian Supreme Court of Cassation concerning the fundamental question of the direct effect of international sources on the protection of human rights in my country. -

In Search of the Law Governed State

THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH TITLE: IN SEARCH OF THE LAW-GOVERNED STAT E Conference Paper #17 of 1 7 Commentary : The Printed versions of Conference Remarks by Participant s AUTHOR: Berman et al . CONTRACTOR: Lehigh University PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Donald D. Barry COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 805-0 1 DATE : October 199 1 The work leading to this report was supported by funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research. The analysis and interpretations contained in the report are those of the author. NCSEER NOTE This paper is #17 in the series listed on the following page. The series is the product of a major conferenc e entitled, In Search of the Law-Governed State: Political and Societal Reform Under Gorbachev, which was summarized in a Council Report by that title authored by Donald D . Barry, and distributed by the Council i n October, 1991. The remaining papers were distributed seriatim . This paper was written prior to the attempted coup of August 19, 1991 . The Conference Papers 1. GIANMARIA AJANI, "The Rise and Fall of the Law-Governed Stat e in the Experience of Russian Legal Scholarship . " 2. EUGENE HUSKEY , "From Legal Nihilism to Pravovoe Gosudarstvo : Soviet Legal Development, 1917-1990 . " 3. LOUISE SHELLEY, "Legal Consciousness and the Pravovoe Gosudarstvo . " 4. DIETRICH ANDRE LOEBER, "Regional and National Variations : The Baltic Factor . " 5. JOHN HAZARD, "The Evolution of the Soviet Constitution . " 6. FRANCES FOSTER-SIMONS, "The Soviet Legislature : Gorbachev' s School of Democracy . " 7. GER VAN DEN BERG, "Executive Power and the Concept of Pravovo e Gosudarstvo . -

Information Note on the Court's Case-Law No

Information Note on the Court’s case-law No. 144 August-September 2011 Ullens de Schooten and Rezabek v. Belgium - 3989/07 Judgment 20.9.2011 [Section II] Article 6 Administrative proceedings Criminal proceedings Article 6-1 Fair hearing Refusal by supreme courts to refer a preliminary question to the European Court of Justice: no violation Facts – Refusal by the Court of Cassation and the Conseil d’Etat to refer questions relating to the interpretation of European Community law, raised in proceedings before those courts, to the Court of Justice of the European Communities (now the Court of Justice of the European Union) for a preliminary ruling. Law – Article 6 § 1: The Court noted that in its CILFIT judgment*, the Court of Justice of the European Communities (“the Court of Justice”) had ruled that courts and tribunals against whose decisions there was no judicial remedy were not required to refer a question where they had established that it was not relevant or that the Community provision in question had already been interpreted by the Court of Justice, or where the correct application of Community law was so obvious as to leave no scope for any reasonable doubt. The Court further reiterated that the Convention did not guarantee, as such, any right to have a case referred by a domestic court to another national or international authority for a preliminary ruling. Where, in a given legal system, other sources of law stipulated that a particular field of law was to be interpreted by a specific court and required other courts and tribunals to refer to it all questions relating to that field, it was in accordance with the functioning of such a mechanism for the court or tribunal concerned, before granting a request to refer a preliminary question, to first satisfy itself that the question had to be answered before it could determine the case before it. -

Appendix to Petition

APPENDIX i TABLE OF CONTENTS – APPENDICES Appendix A (Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit sitting en banc, Nov. 2, 2009) ............................... 1a Majority Opinion ......................................... 5a Dissenting Opinion of Judge Sack ............ 54a Dissenting Opinion of Judge Parker....... 125a Dissenting Opinion of Judge Pooler........ 157a Dissenting Opinion of Judge Calabresi .. 173a Appendix B (Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, Jun. 30, 2008) ..................................................... 195a Majority Opinion ..................................... 200a Dissenting Opinion of Judge Sack .......... 276a Appendix C (Opinion of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York, Feb. 16, 2006) ........................................... 335a Appendix D (Torture Victim Protection Act of 1991, Public Law 102-256 Stat 73, 28 USC § 1350).................................................... 427a ii Appendix E (Excerpts of the Foreign Affairs Reform and Restructuring Act of 1998, Public Law 111-125, 8 USCS § 1231.............................. 431a Appendix F (Excerpts of the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment) ....................................................... 434a Appendix G (Complaint with Exhibits)............. 438a Complaint ................................................ 438a EXHIBIT A: Syria – Country Reports on Human Rights 2002: Dated March 31, 2003................................................... -

Constitutional Courts Versus Supreme Courts

SYMPOSIUM Constitutional courts versus supreme courts Lech Garlicki* Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icon/article/5/1/44/722508 by guest on 30 September 2021 Constitutional courts exist in most of the civil law countries of Westem Europe, and in almost all the new democracies in Eastem Europe; even France has developed its Conseil Constitutionnel into a genuine constitutional jurisdiction. While their emergence may be regarded as one of the most successful improvements on traditional European concepts of democracy and the rule of law, it has inevitably given rise to questions about the distribution of power at the supreme judicial level. As constitutional law has come to permeate the entire structure of the legal system, it has become impossible to maintain a fi rm delimitation between the functions of the constitutional court and those of ordinary courts. This article looks at various confl icts arising between the higher courts of Germany, Italy, Poland, and France, and concludes that, in both positive and negative lawmaking, certain tensions are bound to exist as a necessary component of centralized judicial review. 1 . The Kelsenian model: Parallel supreme jurisdictions 1.1 The model The centralized Kelsenian system of judicial review is built on two basic assu- mptions. It concentrates the power of constitutional review within a single judicial body, typically called a constitutional court, and it situates that court outside the traditional structure of the judicial branch. While this system emerged more than a century after the United States’ system of diffused review, it has developed — particularly in Europe — into a widely accepted version of constitutional protection and control. -

The Reality of EU-Conformity Review in France

Syracuse University SURFACE College of Law - Faculty Scholarship College of Law Summer 7-26-2012 The Reality of EU-Conformity Review in France Juscelino F. Colares Case Western Reserve University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/lawpub Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Colares, Juscelino F., "The Reality of EU-Conformity Review in France" (2012). College of Law - Faculty Scholarship. 66. https://surface.syr.edu/lawpub/66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Law - Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Reality of EU-Conformity Review in France ∗ Juscelino F. Colares "Il ne peut y avoir égalité devant la loi, s'il n'y a pas unité de la loi."1 "The operation of a double system of conflicting laws in the same State is plainly hostile to the reign of law."2 French High Courts embraced review of national legislation for conformity with EU law in different stages and following distinct approaches to EU law supremacy. This article tests whether adherence to different views on EU law supremacy has resulted in different levels of EU directive enforcement by the French High Courts. After introducing the complex French systems of statutory, treaty and constitutional review, this study explains how EU- conformity review emerged among these systems and provides an empirical analysis refuting the anecdotal view that different EU supremacy theories produce substantial differences in conformity adjudication outcomes. -

UNITED NATIONS CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of All

CEDAW/C/LTU/1 English Page 1 CEDAW UNITED NATIONS Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN (CEDAW) CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 18 OF THE CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN Initial report of States parties LITHUANIA Part I Land and people1 Lithuania is located on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea. It borders Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east, and Poland and the Kaliningrad region of the Russian Federation to the south. Lithuania covers an area of 65,300 square kilometres. At the beginning of 1998 the population totalled 3,704 million. The capital of Lithuania is Vilnius. Average income per capita: in the first quarter of 1998, it was 452 litas (LT), and average disposable income per capita was LT 393.7. GDP: in 1996, LT 31,569 million; and in 1997, LT 38,201 million. /... CEDAW/C/LTU/1 English Page 2 Rate of inflation has been decreasing in recent years: in 1994, it was 45.1 per cent, and in 1997, 8.4 per cent. External debt: as of 1 July 1998, it comprised US$ 1,402.70 million. Rate of unemployment: in 1997, 5.9 per cent; in April 1998, 6.9 per cent. Literacy rate: according to the census of 1989, 99.8 per cent of the population 9-49 years of age were literate. Religion: the majority of the population is Roman Catholic. Ethnic composition of the population: according to the data of the beginning of 1997, Lithuanians comprised 81.6 per cent; Russians, 8.2; Poles, 6.9; Belarussians, 1.5; Ukrainians, 1.0; Jews, 0.1; and other nationalities, 0.7 per cent. -

Administrative Justice in Europe

ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE IN EUROPE - ROMANIA REPORT - • INTRODUCTION (History, purpose of the review and classification of administrative acts, definition of an administrative authority) 1. Main dates in the evolution of the review of administrative acts The separation principle has its origins in the Organic Rules (1831, 1832), and has been afterwards established by the Developing Statute of the Paris Convention (1864) as well as the provisions of the Constitutions from 1866, 1923, 1938. Started for the first time in Romania by the Law for founding the State Council from 11th of February 1864, the Law on Administrative Disputes had a remarkable historical evolution, with changes from one political regime to another, determined by the changes that have interfered in the history of our country. The legislation established, initially, the system of the special administrative jurisdiction, then the system of the common competent courts and in matter of administrative disputes, with certain peculiarities in a period or another, but it also mentioned the judge administrator system. This explains why, in the administrative doctrine, in the substantiation of the notion administrative dispute there could not been made an abstraction concerning the aspects regarding the activity of the administrative body with jurisdictional character. After the Revolution from December 1989, the enactment of some special bills (Law no. 29/1990 on Administrative Disputes, replaced by the Law no. 554/2004 on Administrative Disputes) had the role of making from the administrative dispute an effective way to control the legality of the activity of the public administration (executive authority) by the specialized judicial court – the Administrative and Tax Litigations Chamber of the High Court of Cassation and Justice, the Administrative and Tax Litigations Chambers of the Courts of Appeal and of the tribunals – courts that are part of the judicial system. -

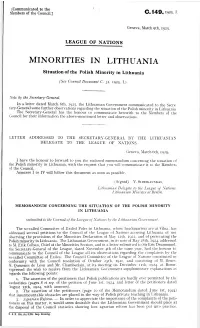

Minorities in Lithuania

[Communicated to the Members of the Council.] C. 149.1 9 2 5 . 1. Geneva, March gth, 1925. LEAGUE OF NATIONS MINORITIES IN LITHUANIA Situation of the Polish Minority in Lithuania (See Council Document C. 31. 1925. I.) Note by the Secretary-General. In a letter dated March 6th, 1925, the Lithuanian Government communicated to the Secre tary-General some further observations regarding the situation of the Polish minority in Lithuania The Secretary-General has the honour to communicate herewith to the Members of the Council for their information the above-mentioned letter and observations. LETTER ADDRESSED TO THE SECRETARY-GENERAL BY THE LITHUANIAN DELEGATE TO THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS. Geneva, March 6th, 1925. I have the honour to forward to you the enclosed memorandum concerning the situation of the Polish minority in Lithuania, with the request that you will communicate it to the Members of the Council. Annexes I to IV will follow this document as soon as possible. (Signed) V. S idzikauskas , Lithuanian Delegate to the League oj Nations. Lithuanian Minister at Berlin. MEMORANDUM CONCERNING THE SITUATION OF THE POLISH MINORITY IN LITHUANIA submitted to the Council of the League oj Nations by the Lithuanian Government. The so-called Committee of Exiled Poles in Lithuania, whose headquarters are at Vilna, has addressed several petitions to the Council of the League of Nations accusing Lithuania of not observing the provisions of the Minorities Declaration of May 12th, 1922, and of persecuting the Polish minority in Lithuania. The Lithuanian Government, in its note of May 28th, 1924, addressed to M. -

Court Precedent – the Estonian Approach

Court Precedent – the Estonian Approach Presentation at the conference "Court Precedent – the Baltic Experience" Vilnius, 15 September 2016 Introduction In my short presentation I will try to give you an overview of the nature and role of the court precedent in the Estonian legal order. It must be asked, as a preliminary point, what do we actually have in mind when talking about court precedent (or judge-made law) in the context Continental European legal system? In 1998, an act was passed in Estonia by which the decisions of the Supreme Court were deemed to be a source of criminal procedural law. Also according to the current Code of Criminal Procedure (Section 2 subsection 4) the sources of criminal procedural law are decisions made by the Supreme Court in issues that are not regulated by other sources of criminal procedural law but which arise in the application of law. It must be noted that in other areas of the law the Estonian legislator has not recognised the decisions of the Supreme Court explicitly as a source of law. Let it also be mentioned that aspects of EU and international law (primarily ECHR practice), which in reality have an impact on the activities of national courts in the interpretation and development of the law, will not be considered in the following presentation. Court precedent – inevitable and necessary The constitutional principle of a state based on the rule of law involves legal certainty, among other things. According to Supreme Court practice, legal certainty in the most general sense, means that the law serves the purpose of creating order and stability in the society.1 In the continental legal system, it is known that laws are of crucial importance in ensuring legal certainty. -

Teisejų Taryba Lithuania

Response questionnaire project group Timeliness Teisėjų Taryba (Lithuania) 1. The Court System and Available Statistics 1.1. The Court System A court system of the Republic of Lithuania is made up of courts of general jurisdiction and courts of special jurisdiction. Courts of general jurisdiction. The Supreme Court of Lithuania (1), the Court of Appeal of Lithuania (1), regional courts (5) and district courts (54) are courts of general jurisdiction dealing with civil and criminal cases. A district court is first instance for criminal, civil cases and cases of administrative offences (assigned to its jurisdiction by law), cases assigned to the jurisdiction of mortgage judges, as well as cases relating to the enforcement of decisions and sentences. A regional court is first instance for criminal and civil cases assigned to its jurisdiction by law, and appeal instance for judgements, decisions, rulings and orders of district courts. The Court of Appeal is appeal instance for cases heard by regional courts as courts of first instance. It also hears requests for the recognition of decisions of foreign or international courts and foreign or international arbitration awards and their enforcement in the Republic of Lithuania, as well as performs other functions assigned to the jurisdiction of this court by law. The Supreme Court of Lithuania is the only court of cassation instance for reviewing effective judgements, decisions, rulings and orders of the courts of general jurisdiction. These courts also hear family, labour and other civil cases, because there are no other courts established special for these cases. The regional courts, the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Lithuania have Civil and Criminal Divisions. -

The Filtering of Appeals to the Supreme Courts

NETWORK OF THE PRESIDENTS OF THE SUPREME JUDICIAL COURTS OF THE EUROPEAN UNION Dublin Conference November 26-27, 2015 Farmleigh House Farmleigh Castleknock, Dublin 15, Ireland INTRODUCTORY REPORT The Filtering of Appeals to the Supreme Courts Rimvydas Norkus President of the Supreme Court of Lithuania Colloquium organised with the support of the European Commission Colloque organisé avec le soutien de la Commission européenne I. Introduction. On the Nature of Appeal to Supreme Court Part VIII of the Constitution of 3rd May 1791 of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the first constitution of its type in Europe, stated that the judicial authority shall not be carried out either by the legislative authority or by the King, but by magistracies instituted and elected to that end. The Constitution also mentioned appellate courts and the Supreme Court. The Constitution did not address in any way filtering of appeals. However, even long before the Constitution of 1791 was adopted, the Third Statute of Grand Duchy of Lithuania, approved in 1588, forbid to appeal intermediate decisions of lower courts to the Supreme Tribunal of the Grand Duchy. Later laws of the Grand Duchy have even established a fine for not complying with this provision. Thus the necessity to limit a right of application to Supreme Court was understood and recognized by a legal system of Lithuania long ago. Historical sources and researches reveal to us now that one of the main reasons why this was done was in fact huge workload of a superior court and delay that was not uncommon in those times. It could take ten or more years to decide some cases before the Supreme Tribunal of the Grand Duchy.