Consultation Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Was Australia's First Declared Vexatious Litigant. an Inventor, Entrepre

Inventor, Entrepreneur, Rascal, Crank or Querulent?: Australia’s Vexatious Litigant Sanction 75 Years On Grant Lester Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, Australia Simon Smith Monash University, Australia upert Frederick Millane (1887–1969) was Australia’s first declared vexatious litigant. An inventor, entrepre- neur, land developer, transport pioneer and self-taught litigator, his extraordinary flood of unsuccessful litiga- Rtion in the 1920s led Victoria to introduce the vexatious litigant sanction now available to most Australian superior courts. Once declared, a vexatious litigant cannot issue further legal proceedings without the leave of the court. Standing to seek the order is usually restricted to an Attorney-General. It is used as a sanction of ‘last resort’. But who was Millane and what prompted his declaration in 1930? What does psychiatry have to say about the persistent complainant and vexatious litigant? How often is the sanction used anyway? What is its utility and the nature of the emerging legislative changes? Now, on the 75th anniversary of Millane’s declaration, this article examines these issues. The Making of a Vexatious Litigant such litigants without the court’s prior leave.1 It The Early Years provided the model for similar provisions in most superior court jurisdictions in Australia. In 1930, Rupert Frederick Millane, inventor, entrepreneur, Millane became the first person in Australia land developer, transport pioneer and self-taught declared a vexatious litigant. litigator was, by any measure, an extraordinary Born in 1887, in the Melbourne suburb of man. A gentle soul, he could spot the ‘big idea’, Hawthorn, Millane was the fourth of five children would promote it determinedly, but could not of Patrick and Annie Millane. -

Texas Supreme Court Update

Texas Supreme Court Update Opinions Issued March 17, 2017 By Stephen Gibson1 (c) 2017 Defamation: Defamatory Effect Is Determined by a Publication’s “Gist” as Understood by an Objectively Reasonable Person; “Gist” May Not Be Decided Solely From Crowd-Sourced Resources. D Magazine Partners, L. P. v. Rosenthal involved a publisher’s motion to dismiss a defamation suit pursuant to the Texas Citizen’s Participation Act (TCPA). Rosenthal sued D Magazine for an article referring to her as a “welfare queen.” The article pointed out that Rosenthal received benefits under the state Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program while living in one of Dallas’s most affluent areas. Rosenthal maintained that the gravamen of the article was that she had engaged in welfare fraud. An earlier investigation by the Texas Health & Human Resources Commission found no wrongdoing, however. Under the TCPA, defendants may move to dismiss as unmeritorious suits “based on, relate[d] to, or … in response to a party’s exercise of the right of free speech.” Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code. § 27.003(a). According to Justice Lehrmann’s opinion, the TCPA’s dismissal provisions are designed to balance protecting a defendant’s free speech rights from vexatious litigation against preventing defamation of the plaintiff’s by constitutionally unprotected speech.2 To avoid dismissal, the plaintiff must present clear and convincing evidence of a prima facie case for each element of the claim subject to the TCPA. Even if the plaintiff meets this burden, the defendant may nevertheless obtain dismissal proving each element of a valid defense by a preponderance of the evidence. -

United States District Court

Case 1:11-cv-00394-LJO-GSA Document 37 Filed 05/29/14 Page 1 of 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 11 THOMAS GOOLSBY, 1:11-cv-00394-LJO-GSA-PC 12 Plaintiff, FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS, RECOMMENDING THAT DEFENDANT 13 vs. STEADMAN‟S MOTION TO DECLARE PLAINTIFF A VEXATIOUS LITIGANT 14 FERNANDO GONZALES, et al., AND REQUIRE PAYMENT OF SECURITY BE DENIED, AND PLAINTIFF‟S MOTION 15 Defendants. FOR STAY AND TO CONDUCT DISCOVERY BE DENIED 16 (Docs. 31, 36.) 17 OBJECTIONS, IF ANY, DUE WITHIN THIRTY DAYS 18 19 20 21 I. BACKGROUND 22 Thomas Goolsby (“Plaintiff”) is a state prisoner proceeding pro se and in forma 23 pauperis with this civil rights action filed pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Plaintiff filed the 24 Complaint commencing this action on March 8, 2011. (Doc. 1.) This case now proceeds on 25 26 27 28 1 Case 1:11-cv-00394-LJO-GSA Document 37 Filed 05/29/14 Page 2 of 6 1 Plaintiff‟s First Amended Complaint, filed on September 17, 2012, against defendant T. 2 Steadman (“Defendant”) for retaliation in violation of the First Amendment.1 (Doc. 13.) 3 On April 17, 2014, Defendant filed a motion to declare Plaintiff a vexatious litigant and 4 require payment of security. (Doc. 31.) On May 21, 2014, Plaintiff filed a motion for stay and 5 to conduct discovery, or in the alternative, a sixty-day extension of time. (Doc. 36.) 6 II. MOTION TO DECLARE PLAINTIFF A VEXATIOUS LITIGANT AND 7 REQUIRE PAYMENT OF SECURITY 8 A. -

Third Party Litigation Funding: Plaintiff Identity and Other Vexing Issues

Third Party Litigation Funding: Plaintiff Identity and Other Vexing Issues Introduction Third party litigation funding arises in both private arrangements and in public (statutory) models of subsidization or support. Third party litigation funding, whether private or public, may give rise to complicated issues such as the identity of the “real” litigant, as well as the consequences of costs awards when the status of the nominal litigant as the “real” party may be in doubt. When the source of funding is public, policy issues may arise about the appropriate scope of the funding. This paper will examine Canadian cases illustrating how courts determine the validity of private third party litigation funding and the issue of who is the “real” party to litigation when such funding arrangements exist. The traditional common law and policy reasons against private third party litigation funding will be assessed, and contrasted with the most significant justification for such funding: promoting access to justice. This paper will also compare private third party litigation funding with statutory funding available in subrogated or vested rights (such as personal injury litigation undertaken by workers’ compensation boards with respect to injured claimants) and statutory funding available from provincial class proceeding funds, government legal aid plans, and workers’ compensation free advisory/advocacy services. Some of the advantages and problems in both private funding and public funding schemes will be assessed, with a look at the factors that influence decision-makers in reaching conclusions about the identity of parties to litigation, as well as what types of costs may be awarded and who bears (or should bear) the obligation for payment of those costs.1 Private litigation funding by third parties as a business transaction 1 In situations where a private third party is funding either legal fees and/or litigation disbursements, the third party funder’s identity as the “real” litigant may be an issue when maintenance and champerty are raised as defenses in the litigation. -

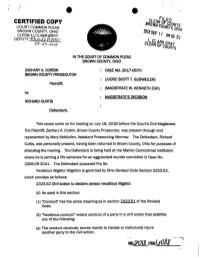

Vexatious Litigator Declaration

• -- '· CERTIFIED COPY COURT COMMON PLEAS BROWN COUNTY, OHIO CLER~~CL%l~RAY DEPUTY:f5.tlJ}1.~ 0 C/-,R 5-~o, B IN THE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS BROWN COUNTY, OHIO ZACHARY A. CORBIN CASE NO. 2017-0570 BROWN COUNTY PROSECUTOR (JUDGE SCOTT T. GUSWEILER) Plaintiff, (MAGISTRATE W. KENNETH ZUK) vs. MAGISTRATE'S DECISION RICHARD CURTIS Defendant. This cause came on for hearing on July 18, 2018 before the Court's Civil Magistrate. The Plaintiff, Zachary A. Corbin, Brown County Prosecutor, was present through and represented by Mary McMullen, Assistant Prosecuting Attorney. The Defendant, Richard Curtis, was personally present, having been returned to Brown County, Ohio for purposes of attending the hearing. The Defendant is being held at the Marion Correctional Institution where he is serving a life sentence for an aggravated murder conviction in Case No. 2009-CR-2041. The Defendant appeared Pro Se. Vexatious litigator litigation is governed by Ohio Revised Code Section 2323.52, which provides as follows: 2323.52 Civil action to declare person vexatious litigator. (A) As used in this section: (1) "Conduct" has the same meaning as In section 2323.51 of the Revised Code. (2) "Vexatious conduct11 means conduct of a party in a civil action that satisfies any of the following: (a) The conduct obviously serves merely to harass or maliciously injure another party to the civil action. -- ' - (b) The conduct is not warranted under existing law and cannot be supported by a good faith argument for an extension, modification, or reversal of existing law. (c) The conduct is imposed solely for delay. -

Third-Party Funding of American Litigation

REVOLUTION IN PROGRESS: THIRD-PARTY FUNDING OF AMERICAN LITIGATION Jason Lyon* There is a growing phenomenon of for-profit investment in U.S. litigation. In a modern twist on the contingency fee, third-party lenders finance all or part of a plaintiff’s legal fees in exchange for a share of any judgment or settlement in the plaintiff’s favor. There are a number of international corporations, both public and private, that invest exclusively in this new “market.” Critics contend that third-party litigation finance violates the common law doctrines of “maintenance,” or interference in a legal proceeding by a stranger to the suit, and “champerty,” or maintenance for profit. Critics also raise numerous arguments based on the purported negative consequences of a widespread system of third-party finance. These include serious ethical considerations, the possibility of compromising attorney-client privilege, and an alleged tendency to encourage frivolous lawsuits while discouraging settlement. This Comment argues that these critiques are flawed and that third-party litigation finance should be permitted but regulated to guard against its fairly limited dangers. I argue, first, that the common law doctrines of maintenance and champerty are inconsistent with our contemporary view of litigation. Over the past century, Americans have come to see lawsuits as a valid means of settling personal disputes, vindicating individual rights, and correcting social ills. Moreover, the procedural reforms of the early twentieth century were designed to liberalize rather than limit access to the courts. I conclude that third-party litigation finance is in keeping with our current values because it facilitates the filing of claims that might otherwise go unheard. -

Self-Represented Litigants & Legal Doctrines of “Vexatiousness”

The Self-Represented Litigants Case Law Database Occasional Research Series (Paper 6) Self-Represented Litigants & Legal Doctrines of “Vexatiousness” An Interim Report from The National Self-Represented Litigants Project Canadian family cases 2013 – 2017, & civil cases 2013 – 2014 December 2019 Megan Campbell & Julie Macfarlane Table of Contents 1. Introduction and Background 3 2. Data Period 4 3. Defining a Vexatious Litigant 4 4. Defining “Vexatious Lite” 5 5. Formal Vexatiousness and Vexatious Lite: Provincial Applications 6 6. Formal Vexatiousness and the “Last Resort” Approach 6 7. Relationship Between Formal Designation as a Vexatious Litigant and Procedural Fairness 7 8. Formal Vexatiousness and Costs 9 9. Formal Vexatiousness and Persons with Disabilities 9 10. Formal Vexatiousness and Gender 10 11. Relationship Between “Vexatiousness Lite” and the Other CLD parameters 11 a) Vexatious Lite and “Procedural Fairness” 11 b) Vexatious Lite and Punitive/Substantial Costs 12 c) Vexatious Lite Cases Involving Both Punitive/Substantial Costs and Procedural Fairness 13 d) Vexatious Lite and Persons with Disabilities 14 e) Vexatious Lite and Gender 14 12. Conclusions 14 2 1. Introduction and Background The Self-Represented Litigants Case Law Database Project (the “CLD” Project) is a research initiative of the National-Self-Represented Litigants Project and as such, an extension of Director Julie Macfarlane’s original 2013 Study on Self-Represented Litigants (“SRLs”). The CLD tracks emerging jurisprudence across Canada which affects SRLs. The development of the CLD was driven by the fact that no other organization in Canada was systematically tracking and analyzing case decisions on SRLs. To date, NSRLP researchers have identified more than 600 important cases that fall within our parameters (below) and over 360 Canadian decisions have been analyzed and entered into the database. -

Psychopathology and Hyperlitigious Litigants

REGULAR ARTICLE I’ll See You in Court...Again: Psychopathology and Hyperlitigious Litigants C. Adam Coffey, MS, Stanley L. Brodsky, PhD, and David M. Sams, JD, LLM Persistent litigation is a problem in many legal jurisdictions and is costly at individual and systemic levels. This phenomenon is referred to as “querulous” behavior in psychiatric literature, whereas legal discourse refers to it as “vexatious litigation.” We refer to this phenomenon as “hyperlitigious behavior” and those who engage in these actions as “hyperlitigious litigants.” Hyperlitigious litigants and hyperlitigious behavior were once the focus of a considerable amount of psychiatric literature, but research devoted to these topics has declined over the past half century. A review of the published literature on hyperlitigious behavior in European and English-speaking countries highlights geographic differences in the conceptualization and management of this behavior. We provide an alternative framework to consider the motivation to engage in hyperlitigious behavior and suggest three strategies for mental health professionals who interact with these individuals. Finally, we call for a revival of discussions and research within the English-speaking psychiatric community to facilitate more informed decisions regarding the management and treatment of hyperlitigious behavior. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 45:62–71, 2017 Again? How many times do you want me to sue them? If “Then there is Snell versus everybody else.” While memory serves me correctly, this will be the 17th time you have brought suit over the same issue!1 obviously comical, Snell’s character nicely illustrates the concept of the hyperlitigious person. Fans of the British TV comedy Kingdom,1 which Although the quote refers to a fictional character, it aired from 2007 to 2009, may recognize this quota- may have reminded you of a problem client or examinee tion. -

Frivolous and Bad Faith Claims: Defense Strategies in Employment Litigation

Frivolous and Bad Faith Claims: Defense Strategies in Employment Litigation A Lexis Practice Advisor® Practice Note by Ellen V. Holloman and Jaclyn A. Hall, Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft, LLP Ellen Holloman Jaclyn Hall This practice note provides guidance on defending frivolous and bad faith claims in employment actions. While this practice note generally covers federal employment law claims, many of the strategies discussed below also apply to state employment law claims. When handling employment law claims in state court be sure to check the applicable state laws and rules. This practice note specifically addresses the following key issues concerning frivolous and bad faith claims in employment litigation: ● Determining If a Claim Is Frivolous or in Bad Faith ● Motion Practice against Frivolous Lawsuits ● Additional Strategies Available against Serial Frivolous Filers ● Alternative Dispute Resolution ● Settlement ● Attorney’s Fees and Costs ● Dealing with Frivolous Appeals Be mindful that frivolous and bad faith claims present particular challenges. On the one hand, if an employee lawsuit becomes public, there is a risk of reputational harm and damage even where the allegations are clearly unfounded. On the other hand, employers that wish to quickly settle employee complaints regardless of the lack of merit of the underlying allegations to avoid litigation can unwittingly be creating an incentive for other employees to file similar suits. Even claims that are on their face patently frivolous and completely lacking in evidentiary support will incur legal fees to defend. Finally, an award of sanctions and damages could be a Pyrrhic victory if a bad-faith plaintiff does not have the resources to pay. -

Responding to Unreasonably Persistent Litigants

Responding to unreasonably persistent litigants September 2014 Chris Wheeler Deputy NSW Ombudsman [This is the manuscript of an article published in The Judicial Review, Vol 12 – Number 1, September 2014] ISBN: 978-1-925569-65-0 The Judicial Review, Vol 12 – Number 1, September 2014 Introduction In 2006, the nine Australasian parliamentary ombudsman began a joint project to identify strategies and techniques to better manage what we referred to as “unreasonable complainant conduct”. This was our first joint project and culminated in the publication of a set of guidelines.1 This project was initiated in response to the noticeable growth in the number of complainants presenting with behaviours that are increasingly challenging and serious.2 We are seeing more complainants who are very angry, aggressive and abusive to our staff; who are threatening harm, who are dishonest or intentionally misleading in presenting the facts, or who deliberately withhold information from us. Our offices are frequently flooded with unnecessary telephone calls, emails and massive quantities of irrelevant printed material. We are seeing complainants who are insisting on outcomes that are clearly not possible or appropriate, or who are making demands that they are not entitled to make, or who, at the end of the process, are unwilling to accept our decisions and continue to demand that we take further action on their complaints. While these guidelines may assist court (and tribunal) registry staff to manage unreasonable conduct by litigants, they do not necessarily address the issues confronting presiding officers. This article identifies a number of strategies that may help to fill this gap. -

Stage 2 Briefing

Stage 2 Briefing Defamation and Malicious Publications (Scotland) Bill January 2021 Introduction The Law Society of Scotland is the professional body for over 12,000 Scottish solicitors. With our overarching objective of leading legal excellence, we strive to excel and to be a world-class professional body, understanding and serving the needs of our members and the public. We set and uphold standards to ensure the provision of excellent legal services and ensure the public can have confidence in Scotland’s solicitor profession. We have a statutory duty to work in the public interest, a duty which we are strongly committed to achieving through our work to promote a strong, varied and effective solicitor profession working in the interests of the public and protecting and promoting the rule of law. We seek to influence the creation of a fairer and more just society through our active engagement with the Scottish and United Kingdom Governments, Parliaments, wider stakeholders and our membership. The Defamation and Malicious Publications (Scotland) Bill1 was introduced by the Cabinet Secretary for Justice, Humza Yousaf MSP, on 2 December 2019. Scottish Government conducted a consultation2 in April 2019 to which we submitted a response.3 The Convener of our Obligations Committee, John Paul Sheridan, gave evidence to the Justice Committee on 1 September 2020. 4 The Stage 1 Report of the Justice Committee5 was published on 14 October 2020. We broadly support the recommendations and conclusions set out in the Stage 1 Report.6 We also note the Scottish Government’s response, which was published on 29 October.7 The Stage 1 Debate took place on 5 November and Parliament approved the general principles of the Bill. -

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT REFUSES to ENTERTAIN APPEAL by FRIVOLOUS, VEXATIOUS LITIGANT in FEDERAL COURTS Good News for Retaile

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT REFUSES TO ENTERTAIN APPEAL BY FRIVOLOUS, VEXATIOUS LITIGANT IN FEDERAL COURTS Good news for retailers, restaurants, hotels, other places of public accommodation and the disabled community by Martin H. Orlick, 11/20/08 On November 17, 2008, the United States Court granted Evergreen Dynasty Corp.'s motion Supreme Court let stand a key Ninth Circuit for an order that the litigation was part of an Court of Appeals ruling that a “serial plaintiff” implausible, cynical scheme to extort and his attorney, who had filed more than 400 settlements from property and business owners. lawsuits against California businesses, could not file repeated Americans with Disabilities Act of The District Court found the plaintiff and his 1990 (ADA) lawsuits against business owners lawyer were vexatious litigants, imposed without first obtaining court permission. In all mandatory sanctions against both of them, and but one of the 400 cases, the businesses settled required the plaintiff and counsel to get the out of court, avoiding substantial defense costs Presiding Judge’s permission to file new and time needed to fight the litigation. lawsuits. The trial court’s decision was affirmed on appeal. Then, by refusing to grant review, A federal judge in Los Angeles called these the Supreme Court let stand the lower court’s litigation tactics “extortion” and based on decision that frivolous ADA litigation and trumped up claims of injury. The United States litigators will not be entertained in federal court. Supreme Court refused to grant a hearing to To insure that future cases filed by the plaintiff review the appellate court’s highly extraordinary are meritorious, the Presiding Judge must weigh ruling in the case, Molski v.