Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Bank and Gaza 2020 Human Rights Report

WEST BANK AND GAZA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Palestinian Authority basic law provides for an elected president and legislative council. There have been no national elections in the West Bank and Gaza since 2006. President Mahmoud Abbas has remained in office despite the expiration of his four-year term in 2009. The Palestinian Legislative Council has not functioned since 2007, and in 2018 the Palestinian Authority dissolved the Constitutional Court. In September 2019 and again in September, President Abbas called for the Palestinian Authority to organize elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council within six months, but elections had not taken place as of the end of the year. The Palestinian Authority head of government is Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh. President Abbas is also chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization and general commander of the Fatah movement. Six Palestinian Authority security forces agencies operate in parts of the West Bank. Several are under Palestinian Authority Ministry of Interior operational control and follow the prime minister’s guidance. The Palestinian Civil Police have primary responsibility for civil and community policing. The National Security Force conducts gendarmerie-style security operations in circumstances that exceed the capabilities of the civil police. The Military Intelligence Agency handles intelligence and criminal matters involving Palestinian Authority security forces personnel, including accusations of abuse and corruption. The General Intelligence Service is responsible for external intelligence gathering and operations. The Preventive Security Organization is responsible for internal intelligence gathering and investigations related to internal security cases, including political dissent. The Presidential Guard protects facilities and provides dignitary protection. -

Jewish Wisconsin 5774-5775/2013-2014

A GUIDE TO Jewish Wisconsin 5774-5775/2013-2014 Your connection to Jewish Arts, Culture, Education, Camping and Religious Life When Accidents or Injuries Happen to Someone You Love Our Family of Lawyers Will Protect Your Family WhyWhy ChooseChoose AnyoneAnyone Else?Else? ®® 1-800-2-HABUSH 1-800-242-2874 Injuries or Deaths From Motor Vehicle Accidents, Medical Malpractice or Product Defects, Nursing Home Negligence, Elder Care Abuse & All Other Injuries • Helping Injured People for Over 75 Years • Wisconsin’s Largest Personal Injury Law Firm • Free Consultation • More Nationally Board Certified Civil Trial • 100’s of Millions in Settlements and Lawyers Than Any Firm in Wisconsin Verdicts Collected For Our Clients • More Lawyers Listed in The Best Lawyers in • Home and Hospital Visits Available America Than Any Other Personal Injury Firm • No Fees or Costs Unless We Are Successful in Wisconsin • Home, Hospital, Evening & Weekend Appointments Milwaukee Office Waukesha Office West Bend Office 1-414-271-0900 1-262-523-4700 1-262-338-3540 www.habush.comwww.habush.com ART ID: 0593220 VERSION: (v1) jm 091609 DIRECTORY NO.: 2STATE/DIRECTORY: n MilwaukeeJewish.org CLIENT NAME: Habush Habush & Rottier CMR CLIENT NO.: 059-3220 HEADING: AD SIZE: 7.25” x 9.75” BVK JOB NO.: ks 1092 AR NAME/LOCATION: Megan D./Milwaukee SHIPPED: (1)091609 jm EMAIL TO AR Welcome to Jewish Milwaukee Welcome to A Guide to Jewish Wisconsin 5774-5775/2013-2014, We invite you to learn more about The Chronicle a publication of The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle. The Guide is by visiting JewishChronicle.org. Also visit designed to help newcomers become acquainted with our state’s MilwaukeeJewish.org to learn more about the vibrant Jewish community and to help current residents get Milwaukee Jewish Federation, which publishes the most out of what our community has to offer. -

Was Australia's First Declared Vexatious Litigant. an Inventor, Entrepre

Inventor, Entrepreneur, Rascal, Crank or Querulent?: Australia’s Vexatious Litigant Sanction 75 Years On Grant Lester Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, Australia Simon Smith Monash University, Australia upert Frederick Millane (1887–1969) was Australia’s first declared vexatious litigant. An inventor, entrepre- neur, land developer, transport pioneer and self-taught litigator, his extraordinary flood of unsuccessful litiga- Rtion in the 1920s led Victoria to introduce the vexatious litigant sanction now available to most Australian superior courts. Once declared, a vexatious litigant cannot issue further legal proceedings without the leave of the court. Standing to seek the order is usually restricted to an Attorney-General. It is used as a sanction of ‘last resort’. But who was Millane and what prompted his declaration in 1930? What does psychiatry have to say about the persistent complainant and vexatious litigant? How often is the sanction used anyway? What is its utility and the nature of the emerging legislative changes? Now, on the 75th anniversary of Millane’s declaration, this article examines these issues. The Making of a Vexatious Litigant such litigants without the court’s prior leave.1 It The Early Years provided the model for similar provisions in most superior court jurisdictions in Australia. In 1930, Rupert Frederick Millane, inventor, entrepreneur, Millane became the first person in Australia land developer, transport pioneer and self-taught declared a vexatious litigant. litigator was, by any measure, an extraordinary Born in 1887, in the Melbourne suburb of man. A gentle soul, he could spot the ‘big idea’, Hawthorn, Millane was the fourth of five children would promote it determinedly, but could not of Patrick and Annie Millane. -

Judges' Work in International Judicial Education

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CIN\49-3\CIN303.txt unknown Seq: 1 13-APR-17 15:44 From the Court to the Classroom: Judges’ Work in International Judicial Education Toby S. Goldbach† This Article explores international judicial education and training, which are commonly associated with rule of law initiatives and develop- ment projects. Judicial education programs address everything from lead- ership competencies and substantive review of human rights legislation to client service and communication, skills training on docket management software, and alternative dispute resolution. Over the last twenty years, judicial education in support of the rule of law has become big business both in the United States and internationally. The World Bank alone spends approximately U.S. $24 million per year for funded projects prima- rily attending to improving court performance. And yet, the specifics of judicial education remains unknown in terms of its place in the industry of rule of law initiatives, the number of judges who act as educators, and the mechanisms that secure their participation. This Article focuses on the judges’ experiences; in particular, the judges of the Supreme Court of Israel who were instrumental in establishing the International Organiza- tion of Judicial Training. Lawyers, development practitioners, justice experts, and government officials participate in training judges. Less well known is the extent to which judges themselves interact internationally as learners, educators, and directors of training institutes. While much scholarly attention has been paid to finding a global juristocracy in constitutional law, scholars have overlooked the role that judges play in the transnational movement of ideas about court structure, legal procedure, case management, and court administration. -

Texas Supreme Court Update

Texas Supreme Court Update Opinions Issued March 17, 2017 By Stephen Gibson1 (c) 2017 Defamation: Defamatory Effect Is Determined by a Publication’s “Gist” as Understood by an Objectively Reasonable Person; “Gist” May Not Be Decided Solely From Crowd-Sourced Resources. D Magazine Partners, L. P. v. Rosenthal involved a publisher’s motion to dismiss a defamation suit pursuant to the Texas Citizen’s Participation Act (TCPA). Rosenthal sued D Magazine for an article referring to her as a “welfare queen.” The article pointed out that Rosenthal received benefits under the state Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program while living in one of Dallas’s most affluent areas. Rosenthal maintained that the gravamen of the article was that she had engaged in welfare fraud. An earlier investigation by the Texas Health & Human Resources Commission found no wrongdoing, however. Under the TCPA, defendants may move to dismiss as unmeritorious suits “based on, relate[d] to, or … in response to a party’s exercise of the right of free speech.” Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code. § 27.003(a). According to Justice Lehrmann’s opinion, the TCPA’s dismissal provisions are designed to balance protecting a defendant’s free speech rights from vexatious litigation against preventing defamation of the plaintiff’s by constitutionally unprotected speech.2 To avoid dismissal, the plaintiff must present clear and convincing evidence of a prima facie case for each element of the claim subject to the TCPA. Even if the plaintiff meets this burden, the defendant may nevertheless obtain dismissal proving each element of a valid defense by a preponderance of the evidence. -

United States District Court

Case 1:11-cv-00394-LJO-GSA Document 37 Filed 05/29/14 Page 1 of 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 11 THOMAS GOOLSBY, 1:11-cv-00394-LJO-GSA-PC 12 Plaintiff, FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS, RECOMMENDING THAT DEFENDANT 13 vs. STEADMAN‟S MOTION TO DECLARE PLAINTIFF A VEXATIOUS LITIGANT 14 FERNANDO GONZALES, et al., AND REQUIRE PAYMENT OF SECURITY BE DENIED, AND PLAINTIFF‟S MOTION 15 Defendants. FOR STAY AND TO CONDUCT DISCOVERY BE DENIED 16 (Docs. 31, 36.) 17 OBJECTIONS, IF ANY, DUE WITHIN THIRTY DAYS 18 19 20 21 I. BACKGROUND 22 Thomas Goolsby (“Plaintiff”) is a state prisoner proceeding pro se and in forma 23 pauperis with this civil rights action filed pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Plaintiff filed the 24 Complaint commencing this action on March 8, 2011. (Doc. 1.) This case now proceeds on 25 26 27 28 1 Case 1:11-cv-00394-LJO-GSA Document 37 Filed 05/29/14 Page 2 of 6 1 Plaintiff‟s First Amended Complaint, filed on September 17, 2012, against defendant T. 2 Steadman (“Defendant”) for retaliation in violation of the First Amendment.1 (Doc. 13.) 3 On April 17, 2014, Defendant filed a motion to declare Plaintiff a vexatious litigant and 4 require payment of security. (Doc. 31.) On May 21, 2014, Plaintiff filed a motion for stay and 5 to conduct discovery, or in the alternative, a sixty-day extension of time. (Doc. 36.) 6 II. MOTION TO DECLARE PLAINTIFF A VEXATIOUS LITIGANT AND 7 REQUIRE PAYMENT OF SECURITY 8 A. -

Excluded, for God's Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel

Excluded, For God’s Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel המרכז הרפורמי לדת ומדינה -לוגו ללא מספר. Third Annual Report – December 2013 Israel Religious Action Center Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism Excluded, For God’s Sake: Gender Segregation and the Exclusion of Women in Public Space in Israel Third Annual Report – December 2013 Written by: Attorney Ruth Carmi, Attorney Ricky Shapira-Rosenberg Consultation: Attorney Einat Hurwitz, Attorney Orly Erez-Lahovsky English translation: Shaul Vardi Cover photo: Tomer Appelbaum, Haaretz, September 29, 2010 – © Haaretz Newspaper Ltd. © 2014 Israel Religious Action Center, Israel Movement for Reform and Progressive Judaism Israel Religious Action Center 13 King David St., P.O.B. 31936, Jerusalem 91319 Telephone: 02-6203323 | Fax: 03-6256260 www.irac.org | [email protected] Acknowledgement In loving memory of Dick England z"l, Sherry Levy-Reiner z"l, and Carole Chaiken z"l. May their memories be blessed. With special thanks to Loni Rush for her contribution to this report IRAC's work against gender segregation and the exclusion of women is made possible by the support of the following people and organizations: Kathryn Ames Foundation Claudia Bach Philip and Muriel Berman Foundation Bildstein Memorial Fund Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Foundation Inc. Donald and Carole Chaiken Foundation Isabel Dunst Naomi and Nehemiah Cohen Foundation Eugene J. Eder Charitable Foundation John and Noeleen Cohen Richard and Lois England Family Jay and Shoshana Dweck Foundation Foundation Lewis Eigen and Ramona Arnett Edith Everett Finchley Reform Synagogue, London Jim and Sue Klau Gold Family Foundation FJC- A Foundation of Philanthropic Funds Vicki and John Goldwyn Mark and Peachy Levy Robert Goodman & Jayne Lipman Joseph and Harvey Meyerhoff Family Richard and Lois Gunther Family Foundation Charitable Funds Richard and Barbara Harrison Yocheved Mintz (Dr. -

Engendering Relationship Between Jew and America

Oedipus' Sister: Narrating Gender and Nation in the Early Novels of Israeli Women by Hadar Makov-Hasson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies New York University September, 2009 ___________________________ Yael S. Feldman UMI Number: 3380280 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3380280 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 © Hadar Makov-Hasson All Rights Reserved, 2009 DEDICATION בדמי ימיה מתה אמי , וכבת ששים שש שנה הייתה במותה This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my mother Nira Makov. Her love, intellectual curiosity, and courage are engraved on my heart forever. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would have never been written without the help and support of several people to whom I am extremely grateful. First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Professor Yael Feldman, whose pioneering work on the foremothers of Hebrew literature inspired me to pursue the questions that this dissertation explores. Professor Feldman‘s insights illuminated the subject of Israeli women writers for me; her guidance and advice have left an indelible imprint on my thinking, and on this dissertation. -

Third Party Litigation Funding: Plaintiff Identity and Other Vexing Issues

Third Party Litigation Funding: Plaintiff Identity and Other Vexing Issues Introduction Third party litigation funding arises in both private arrangements and in public (statutory) models of subsidization or support. Third party litigation funding, whether private or public, may give rise to complicated issues such as the identity of the “real” litigant, as well as the consequences of costs awards when the status of the nominal litigant as the “real” party may be in doubt. When the source of funding is public, policy issues may arise about the appropriate scope of the funding. This paper will examine Canadian cases illustrating how courts determine the validity of private third party litigation funding and the issue of who is the “real” party to litigation when such funding arrangements exist. The traditional common law and policy reasons against private third party litigation funding will be assessed, and contrasted with the most significant justification for such funding: promoting access to justice. This paper will also compare private third party litigation funding with statutory funding available in subrogated or vested rights (such as personal injury litigation undertaken by workers’ compensation boards with respect to injured claimants) and statutory funding available from provincial class proceeding funds, government legal aid plans, and workers’ compensation free advisory/advocacy services. Some of the advantages and problems in both private funding and public funding schemes will be assessed, with a look at the factors that influence decision-makers in reaching conclusions about the identity of parties to litigation, as well as what types of costs may be awarded and who bears (or should bear) the obligation for payment of those costs.1 Private litigation funding by third parties as a business transaction 1 In situations where a private third party is funding either legal fees and/or litigation disbursements, the third party funder’s identity as the “real” litigant may be an issue when maintenance and champerty are raised as defenses in the litigation. -

Vexatious Litigator Declaration

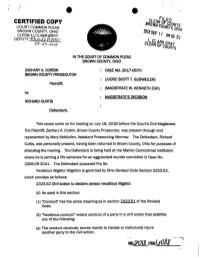

• -- '· CERTIFIED COPY COURT COMMON PLEAS BROWN COUNTY, OHIO CLER~~CL%l~RAY DEPUTY:f5.tlJ}1.~ 0 C/-,R 5-~o, B IN THE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS BROWN COUNTY, OHIO ZACHARY A. CORBIN CASE NO. 2017-0570 BROWN COUNTY PROSECUTOR (JUDGE SCOTT T. GUSWEILER) Plaintiff, (MAGISTRATE W. KENNETH ZUK) vs. MAGISTRATE'S DECISION RICHARD CURTIS Defendant. This cause came on for hearing on July 18, 2018 before the Court's Civil Magistrate. The Plaintiff, Zachary A. Corbin, Brown County Prosecutor, was present through and represented by Mary McMullen, Assistant Prosecuting Attorney. The Defendant, Richard Curtis, was personally present, having been returned to Brown County, Ohio for purposes of attending the hearing. The Defendant is being held at the Marion Correctional Institution where he is serving a life sentence for an aggravated murder conviction in Case No. 2009-CR-2041. The Defendant appeared Pro Se. Vexatious litigator litigation is governed by Ohio Revised Code Section 2323.52, which provides as follows: 2323.52 Civil action to declare person vexatious litigator. (A) As used in this section: (1) "Conduct" has the same meaning as In section 2323.51 of the Revised Code. (2) "Vexatious conduct11 means conduct of a party in a civil action that satisfies any of the following: (a) The conduct obviously serves merely to harass or maliciously injure another party to the civil action. -- ' - (b) The conduct is not warranted under existing law and cannot be supported by a good faith argument for an extension, modification, or reversal of existing law. (c) The conduct is imposed solely for delay. -

Israel 2020 Human Rights Report

ISRAEL 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, its parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “state of emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve itself and mandate elections. On March 2, Israel held its third general election within a year, which resulted in a coalition government. On December 23, following the government’s failure to pass a budget, the Knesset dissolved itself, which paved the way for new elections scheduled for March 23, 2021. Under the authority of the prime minister, the Israeli Security Agency combats terrorism and espionage in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. The national police, including the border police and the immigration police, are under the authority of the Ministry of Public Security. The Israeli Defense Forces are responsible for external security but also have some domestic security responsibilities and report to the Ministry of Defense. Israeli Security Agency forces operating in the West Bank fall under the Israeli Defense Forces for operations and operational debriefing. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security services. The Israeli military and civilian justice systems have on occasion found members of the security forces to have committed abuses. Significant human -

ISRAEL Israel Is a Multiparty Parliamentary Democracy with A

ISRAEL Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy with a population of approximately 7.7 million, including Israelis living in the occupied territories. Israel has no constitution, although a series of "Basic Laws" enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a "State of Emergency," which has been in effect since 1948. The 120-member, unicameral Knesset has the power to dissolve the government and mandate elections. The February 2009 elections for the Knesset were considered free and fair. They resulted in a coalition government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Israeli security forces reported to civilian authorities. (An annex to this report covers human rights in the occupied territories. This report deals with human rights in Israel and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights.) Principal human rights problems were institutional, legal, and societal discrimination against Arab citizens, Palestinian residents of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (see annex), non-Orthodox Jews, and other religious groups; societal discrimination against persons with disabilities; and societal discrimination and domestic violence against women, particularly in Bedouin society. While trafficking in persons for the purpose of prostitution decreased in recent years, trafficking for the purpose of labor remained a serious problem, as did abuse of foreign workers and societal discrimination and incitement against asylum seekers. RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life The government or its agents did not commit politically motivated killings. The petitioners withdrew their appeal to the High Court against the closure of the inquiry by the Department for Investigations against Police Officers' (DIPO) into the 2008 beating and subsequent coma and death of Sabri al-Jarjawi, a Bedouin.