Have Your Say

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SA Water Drinking Water Quality

SA Water Drinking Water Quality January 2000 – July 2012 Amended Version: October 21 2012 Image: Myponga Reservoir Compiled by Anthony Amis Thanks to Warren Godson for the idea and support. Without tax deductible donations this project would never have happened. If you would like more information or would like to make a donation contact [email protected] for more details. 1 Table of Contents 1 Glossary p3 1 Background p4 2 Summary p5 3 Adelaide Summary p12 4 SA Water Breaches Summary p15 5. Substances p18 5.1 Antimony p18 5.2 Arsenic p19 5.3 p20 Bromodichloromethane/Dichlorobromoform 5.4 Bromoform p32 5.5 Cadmium p35 5.6 Chloral Hydrate/Trichloroacetalehyde p36 5.7 Chlorate p39 5.8 Chlorine p40 5.9 Chlorine Total p42 5.10 Chloroform p44 5.11 p46 Dibromochloromethane/Dibromochloroform 5.12 Dichloroacetic Acid p50 5.13 E.coli p52 5.14 Fluoride p53 5.15 Lead p54 5.16 Manganese p55 5.17 Mercury p56 5.18 Monochloramines p57 5.19 NDMA p60 5.20 Nickel p63 5.21 Selenium p64 5.22 Trichloroacetic Acid p65 5.23 Trihalomethanes p67 6. Kingscote p75 7. References p79 8. Appendices p80 2 Glossary ADWG: Australian DrinkingWater Guidelines DBCM: Dibromochloroform BDCM: Bromodichloromethane DBP: Disinfection By-Product DCBM: Dichlorobromoform FoE: Friends of the Earth FoI: Freedom of Information IARC: International Agency for Research on Cancer NDMA: N-nitrosodimethylamine THM: Trihalomethanes WHO: World Health Organisation Concentrations in Water mg/L: parts per million (one cup of water in a swimming pool) ug/L: parts per billion (one drop of water in a swimming pool) ng/L: parts per trillion (one thousandth of one drop of water in a swimming pool) Information About Amended Version of this Report. -

A Risk Assessment of the Impact of Farm Dams on Streamflow in Catchments on Kangaroo Island

TECHNICAL NOTE 2007/16 Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation A RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE IMPACT OF FARM DAMS ON STREAMFLOW IN CATCHMENTS ON KANGAROO ISLAND Doug McMurray December 2007 © Government of South Australia, through the Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation 2007 This work is Copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cwlth), no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission obtained from the Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Chief Executive, Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation, GPO Box 2834, Adelaide SA 5001. Disclaimer The Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation and its employees expressly disclaims all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. Information contained in this document is correct at the time of writing. Information contained in this document is correct at the time of writing. ISBN 978-1-921218-76-7 Preferred way to cite this publication McMurray, D 2007, A risk assessment of the impact of farm dams on streamflow in catchments on Kangaroo Island, DWLBC Technical Note 2007/16, Government of South Australia, through Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation, Adelaide. Knowledge and Information Division 25 Grenfell Street, Adelaide GPO Box 2834, Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone National (08) 8463 6946 International +61 8 8463 6946 Fax National (08) 8463 6999 International +61 8 8463 6999 Website www.dwlbc.sa.gov.au CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................3 1. -

Ki Natural Resources Management Board Agenda

KI NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT BOARD AGENDA MEETING 153 to be held Friday 12 April 2019, Boardroom, 35 Dauncey St, Kingscote Verbal Report Paper 2:00 pm start CS Consent Schedule Time # Agenda Item 1:30 pm 1 Meeting Preliminaries (15 mins) 1.1 Welcome Damian Miley 1.2 Apologies 1.3 Presiding member Damian Miley 1 1.4 Declaration of interest by members 1.5 Acceptance of agenda and consent schedule Decision 1 1:45 2 Minutes of Previous Meeting 2.1 Acceptance of previous minutes Decision 2 2.2 Business arising from previous minutes Decision 13 1:30 3 Board Matters: for decision or discussion 3.1 Finance Reports February 2019 J Hughes Decision 16 3.2 Workshop outcomes: D Miley Decision 22 Native plant nursery Feral cat project Feral pig management Draft budget 2019/2020 3.3 Risk and Issues Register J Hughes Decision 23 3.4 Financial Management Compliance Program J Hughes Decision 31 3.5 Working Capital J Hughes Decision 36 3.6 Vessel sharing arrangements and other D Miley Decision 40 matters 3.7 Fraud J Hughes Decision 48 4 Board Matters: Consent Schedule 4.1 Correspondence register CS Noting 53 2:45 5 Any Other Business (15 mins) 6 Board Communique 7 Next Meeting Friday 24 May at 9:30 am 3:00 pm 8 Closure Kangaroo Island NRM Board Meeting 1. Meeting Preliminaries Number 153 – 12 April 2019 1.3 PRESIDING MEMBER Priority For Decision RECOMMENDATIONS That the Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board: 1. Nominate a Presiding Member for this special meeting as per Natural Resources Management Act 2004 schedule 1, 2(2), “if the Presiding member is absent from a meeting a member chosen by the members present at the meeting will preside at the meeting”. -

Kangaroo Island 2018-19 Water Resources Assessment

Kangaroo Island 2018-19 water resources assessment Department for Environment and Water December 2020 DEW Technical report 2020/34 Department for Environment and Water Government of South Australia December 2020 81-95 Waymouth St, ADELAIDE SA 5000 Telephone +61 (8) 8463 6946 Facsimile +61 (8) 8463 6999 ABN 36702093234 www.environment.sa.gov.au Disclaimer The Department for Environment and Water and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The Department for Environment and Water and its employees expressly disclaims all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. Information contained in this document is correct at the time of writing. With the exception of the Piping Shrike emblem, other material or devices protected by Aboriginal rights or a trademark, and subject to review by the Government of South Australia at all times, the content of this document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence. All other rights are reserved. © Crown in right of the State of South Australia, through the Department for Environment and Water 2020 ISBN 978-1-925964-85-1 Preferred way to cite this publication DEW (2020). Kangaroo Island 2018-19 water resources assessment, DEW Technical report 2020/34, Government of South Australia, Department for Environment and Water, Adelaide. Download this document at https://www.waterconnect.sa.gov.au -

ACERS Kangaroo Island and Adelaide Mount Lofty Ranges

Water quality Information Sheet Aquatic ecosystem condition reports 2013 panel assessment of creeks and rivers from the Kangaroo Island and Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges NRM regions Issued July 2014 EPA 1048/14: This information sheet describes the outcome of the panel assessment of creeks and rivers from the Kangaroo Island and Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management (NRM) regions, sampled during autumn and spring 2013. Introduction The Environment Protection Authority (EPA) coordinates a monitoring, evaluation and reporting (MER) program on the aquatic ecosystem condition of South Australian creeks and rivers. This MER program is designed to meet several objectives: • Providing a statewide monitoring framework for creeks and rivers that revolves through the NRM regions with sufficient frequency to allow for state of the rnvironment reporting purposes. • Describing aquatic ecosystem condition for broad general public understanding. • Identifying the key pressures and management responses to those pressures. • Providing a useful reporting format that can support environmental decision making within government, community and industry. This information sheet provides a summary of the scientific work used in assessing monitoring data from creeks and rivers. Aquatic ecosystem science is not always rigid and precise; it is often open to different interpretations in several respects. Therefore, the EPA has decided that the best way to assess the condition of streams is through an expert panel deliberation that uses a consistent descriptive modelling approach. The panel members comprised an environmental consultant and two biologists from the EPA (the authors of this assessment). All have at least 15 years’ experience in monitoring and assessing a range of streams across South Australia. -

Drinking Water Quality Report 2013-14

SA Water Drinking Water Quality Report 2013-14 Government of South Australia 4 / A Message from our Chief Executive 5 / SA Health Statement 5 / Economic Regulation 6 / Safe Drinking Water Legislation 7 / The Adelaide Services Alliance 8 / Drinking Water Quality Management 13 / Our Water Supply Systems 13 / Our water supply sources 15 / Water treatment 20 / Country drinking water supply system sources and treatment 22 / Metropolitan Adelaide water treatment plant sources 23 / Metropolitan Adelaide water quality systems and treatment 24 / Drinking water supply systems and towns/suburbs supplied 27 / Managing our water supplies 29 / Water Quality 2013–14 29 / Catchments, land management and source water 33 / Water treatment and distribution 34 / Water quality monitoring and testing 35 / Drinking water quality and performance 37 / Customer satisfaction 38 / Incident management 40 / Research and Innovation 42 / Employee Awareness and Training 44 / Glossary of Water Quality Terminology 48 / 2013–14 Water Quality Data This report covers the period of 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014. Total water usage (raw water for treatment) 2013-14 213 926 ML Population served Highlights 1 173 000 in metropolitan Adelaide through 9 190 km of water mains Raw water sources Number of routine 432 000 in country areas through % of total water supplied water quality tests 17 582 km of water mains. carried out River Murray: 36% 295 519 (total) Drinking water quality and performance Surface water: 30% 49 529 (metropolitan Adelaide) Seawater: 28% 43 862 of the routine 245 990 samples collected from our drinking Groundwater: 6% (country) water supplies throughout South Australia were used to determine health-related compliance. -

SA Water's Long Term Plan for Kangaroo Island

SSAA Water’sWater’s LongLong TermTerm PlanPlan forfor KKangarooangaroo IslandIsland (Including the Middle River and Penneshaw Water Supply Systems) December 2009 Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 1 Background 16 1.1 Long Term Plan Overview 16 1.2 Existing Water Supply Systems 18 2 Community Consultation 21 2.1 Community Engagement and Communication 21 2.2 Strategy Implementation and Outcomes 22 3 Demand 25 3.1 Historical SA Water Demand Information 25 3.2 Census Information 28 3.3 Regional Land Use Framework 29 3.4 Future Demand 29 4 Existing Sources 32 4.1 Middle River 32 4.2 Seawater 33 4.3 Non Reticulated Supplies 33 4.4 Overview of Supply Situation 34 5 Augmentation Options for the Middle River WSS 37 5.1 Assumptions 37 5.2 Construct a Larger Dam at Middle River 38 5.3 Construct a Raw Water Storage near Middle River Reservoir 39 5.4 Construct an In‐system Treated Water Storage 40 5.5 Construct a Small Seawater Desalination Plant 41 5.6 Construct a Large Seawater Desalination Plant 44 5.7 Estimate cost range of options 45 6 Other Considerations 47 6.1 Penneshaw WSS 47 6.2 Supply to townships not currently supplied by SA Water 47 6.3 Water Quality in the Middle River WSS 47 7 Options Assessment – Middle River WSS 49 7.1 Criteria 49 7.2 Weightings 50 2 7.3 Assessment of Options 51 8 Summary and Recommendations 54 8.1 Ongoing Review of the Long Term Plan 54 8.2 Recommendations 55 9 References 56 Appendix A Acronyms The Plan SA Water’s Long Term Plan for Kangaroo Island WSS Water Supply System KINRMB Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics LGA Local Government Areas KIC Kangaroo Island Council PWCM Permanent Water Conservation Measures 3 Executive Summary SA Water’s long term planning The South Australian Government is committed to sustainable water resources for the State’s regions and undertakes long term planning to ensure water supplies can meet demand for the future. -

Biosecurity Requirements

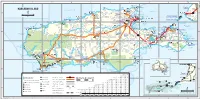

This mapping data is copyright South Australian Tourism Commission (SATC )and Carto Graphics and must not be used without the express permission of the copyright parties. White Boxing Point Bay North Cape Cape Cape Point Marsden Fleurieu Cassini Peninsula D'Estaing Mt Marsden Delamere KANGAROO ISLAND Smith Emu Bay Southern Spencer Gulf Marine Park CASSINI Bay RD 6 1 7 Rockpool Café RD Emu 5 RD Encounter Marine Park RD Discovery Lagoon Bay Cape Rouge Mt McDonnell 7 Caravan & Camping Lavender CAPEBay of RD B23 Cape Stokes Bay 3 Old 9 Shoals Cape Jervis 0 10 Dutton 3 COAST Wisanger 2 Busby Islet NORTH School 3 NORTH Bay of Conservation Park BELL MANOR NORTH COAST Shoals COAST 9 RD 3 Wisanger Busby Islet Kangaroo Island SeaLink km King George 4 6 3 Rettie Wines 8 Lathami 3 SPRINGS 7 ROSE RD 2 Sports Club Conservation Park Passenger & Vehicle Ferry Beach RD Bluff 4 Western 1 Con. Park COTTAGE 3 (Cape Jervis - Penneshaw) Snelling RD 3 RD SPRINGS River Shep’s Studio2 3 1 Beach RD 5 2 NORTH 6 4 3 Kingscote Cove 2 RD PRATTS Kangaroo Island Brewery KI Connect Passenger Ferry 2 GAP RD Island Beehive 7 5 RD 3 2 (Cape Jervis - Penneshaw) Amen Corner Spring Road Cellar Door 5 2 3 Snug WESTERN 7 RD HWY Brownlow RANGE 4 The Islander Estate 3 COCKATOO Cape RD Constitution Stokes Bay Hall BARK 2 CREEK RD Kingscote Cove RIVER 8 2 6 Cellar Door K.I. Spirits 2 Western River BOXER Forbin Hill HUT 5 2 Golf Course 7 RD GUM CREEK RD 1 Wilderness 7 2 McBRIDE 3 4 Racecourse Backstairs 4 4 Nepean Penneshaw Cape Middle RD 2 RD BARK Cygnet Cygnet Estuary Torrens RD Protection 8 3 2 River 2 River BAY HUT Duck Lagoon Conservation Park Bay SNUG MILLERS ARRAMORE 2 1 7 PIONEER RD 5 2 4 COVE RD Dam BEND 2 5 3 Kangaroo Scott Cape Torrens Area JOHNCOCK RD Western Cove Passage 9 RD MAYS 9 5 RD Point Head KI Seafront Holiday Park Cove Harveys Return Wild. -

Water Monitoring Review for the Kangaroo Island Natural Resource Management Region

DWLBC REPORT Water Monitoring Review for the Kangaroo Island Natural Resource Management Region 2006/16 Water Monitoring Review for the Kangaroo Island Natural Resource Management Region Li Wen Knowledge and Information Division Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation July 2007 Report DWLBC 2006/16 Knowledge and Information Division Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation 25 Grenfell Street, Adelaide GPO Box 2834, Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone National (08) 8463 6946 International +61 8 8463 6946 Fax National (08) 8463 6999 International +61 8 8463 6999 Website www.dwlbc.sa.gov.au Disclaimer The Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation and its employees expressly disclaims all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. Information contained in this document is correct at the time of writing. © Government of South Australia, through the Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation 2007 This work is Copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cwlth), no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission obtained from the Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Chief Executive, Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation, GPO Box 2834, Adelaide SA 5001. ISBN 978-1-921218-16-3 Preferred way to cite this publication Wen, L 2005. -

Draft Water Security Statement

Water Security Statement 2021 Water for Sustainable Growth Contents Executive summary ........................................................................................................ i Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 What is water security? .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Why we need to consider water security ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 Who is responsible for water security? ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Why a water security statement? .............................................................................................................................................................................. 5 South Australia’s water resources ............................................................................... 7 Where do we get our water from? ................................................................................................................................................................................ 8 Groundwater ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

State of the Region 2009

Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Plan 2009 Volume 1 State of the Region 2009 Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Plan 2009 © Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board Introduction to the Plan Volume 1 – State of the Region 2009 Volume 2 – Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Strategic Plan 2009–2019 Volume 3 – Implementation A: Regulatory and Operational Policy Volume 4 – Implementation B: Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board Business Plan 2009–2012 Volume 5 – Monitoring, Evaluating, Reporting, Learning and Improving NRM ISBN 978-1-921595-00-4 (paperback) ISBN: 978-1-921595-01-1 (CD-ROM) ISBN: 978-1-921595-02-8 (online) iv KI Natural Resources Management State of the Region 2009 Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................................ 1 Indigenous people................................................................................................................................. 2 Indigenous cultural assets................................................................................................................... 2 Threats to cultural heritage ................................................................................................................. 3 Socioeconomic profile of Kangaroo Island ........................................................................................ 4 Community capacity for natural resources management................................................................ -

View the Kangaroo Island

This mapping data is copyright South Australian Tourism Commission (SATC )and Carto Graphics and must not be used without the express permission of the copyright parties. White Boxing Point Bay North Cape Cape Cape Point Marsden Fleurieu Cassini Peninsula D'Estaing Mt Marsden Delamere KANGAROO ISLAND Smith Emu Bay Southern Spencer Gulf Marine Park CASSINI Bay RD 1 7 Rockpool Café 6 Emu 5 RD Encounter Marine Park RD RD Bay Cape Rouge Mt McDonnell 7 Lavender CAPEBay of RD B23 Cape Stokes Bay 3 Old Cape Jervis 9 NORTH KI Ciders Shoals Busby Islet 0 10 Dutton Table 88 3 COAST Wisanger COAST 2 NORTH School 3 NORTH Bay of Conservation Park BELL MANOR Shoals COAST 9 RD 3 Wisanger Busby Islet Kangaroo Island SeaLink km King George 4 6 3 Rettie Wines 8 Lathami 3 SPRINGS 7 ROSE RD 2 Sports Club Conservation Park Passenger & Vehicle Ferry Beach RD Bluff 4 Western Con. Park RD 3 Snelling 1 3 COTTAGE RD SPRINGS (Cape Jervis - Penneshaw) River Stokes Bay Shep’s Studio2 3 1 Beach RD KI Fishing 5 2 NORTH Bush Garden 6 4 3 RD Kingscote Cove 2 RD PRATTS Kangaroo Island Brewery KI Connect Passenger Ferry Adventures 2 GAP Island Beehive 7 5 RD 3 2 2 (Cape Jervis - Penneshaw) Amen Corner Spring Road Cellar Door 5 3 Snug WESTERN 7 RD HWY Brownlow RANGE 4 The Islander Estate 3 COCKATOO Cape Cove RD Constitution Stokes Bay Hall BARK 2 CREEK RD 2 Kingscote Western River Billygoat FallsRIVER 8 2 6 Cellar Door K.I. Spirits Forbin Hill HUT BOXER 2 Golf Course 7 RD McBRIDE RD 1 5 Waterfall Wilderness 7 2 3 GUM CREEK 4 Racecourse Backstairs 4 4 Nepean Cape Creek Hike Middle RD 2 RD BARK Cygnet Cygnet Estuary Torrens RD Protection 8 3 2 River 2 River BAY HUT Duck Lagoon Conservation Park Bay SNUG MILLERS ARRAMORE 2 1 7 PIONEER RD 5 2 4 COVE RD Dam BEND 2 5 3 Kangaroo Scott Cape Torrens Area JOHNCOCK RD Western Cove Passage 9 RD MAYS 9 5 RD Point Head Penneshaw Cove Harveys Return Wild.