Alsf Aggregate Extraction and the Geoarchaeological Heritage of the Kirkham Moraine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

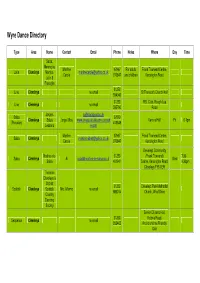

Wyre Dance Directory

Wyre Dance Directory Type Area Name Contact Email Phone Notes Where Day Time Salsa, Merengue, Martine 07967 For adults Frank Townend Centre, Latin Cleveleys Mambo, [email protected] Carole 970847 and children Kensington Road Latin & Freestyle 01253 Line Cleveleys no email St Theresa's Church Hall 594043 01253 RBL Club, Rough Lea Line Cleveleys no email 595790 Road Jorge’s [email protected] Salsa 07879 Cleveleys Salsa Jorge Ulloa www.jorgessalsalessons.yolasit Verona Hall Fri 6-7pm (Peruvian) 413649 Lessons e.com Martine 07967 Frank Townend Centre, Salsa Cleveleys [email protected] Carole 970847 Kensington Road Cleveleys Community Noches-de- 01253 (Frank Townend) 7.30- Salsa Cleveleys Al [email protected] Wed Salsa 401941 Centre, Kensington Road, 9.30pm Cleveleys FY5 1ER Thornton Cleveleys & District 01253 Cleveleys Park Methodist Scottish Cleveleys Scottish Mrs. Marmo no email 886014 Church, West Drive Country Dancing Society Senior Citizens Hall, 01253 Victoria Road, Sequence Cleveleys no email 852462 Anchorsholme Friendly Club Phil Kelsall 01253 Ballroom Fleetwood [email protected] Organists Marine Hall Chris Hopkins 771141 Christine 01253 Ballroom Fleetwood [email protected] Victoria Street Cheeseman 779746 07874 Farmer Parrs, Fleetwood Ballroom / Latin Fleetwood Alison Slinger [email protected] Improvers Fri 7-8pm 922223 Road 07874 Practise Farmer Parrs, Fleetwood Ballroom / Latin Fleetwood Alison Slinger [email protected] Fri 8-9.30 922223 session Road 07874 Social Farmer -

NOTICE of ELECTION AGENTS' NAMES and OFFICES Lancashire

NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS' NAMES AND OFFICES Lancashire County Council Election of a County Councillor for Preston Central East Division on Thursday 4 May 2017 I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them may be sent, have respectively been declared in writing to me as follows: Name of Correspondence Name of Election Agent Address Candidate BORROW 117 Garstang Road, Fulwood, DE MOLFETTA David Preston, PR2 3EB Francesco (Commonly Known As: Frank De Molfetta) VOGES 7 Haighton Drive, Fulwood, TURNER Jurgen Preston, PR2 9LU Michael Clifton (Commonly Known As: Mike Turner) BENNETT 11 Daub Lane, Hoghton, Preston, WHITTAM Warren PR5 0JT Susan Marie (Commonly Known As: Sue Whittam) Dated Tuesday 4 April 2017 Lorraine Norris Deputy Returning Officer Printed and published by the Deputy Returning Officer, Town Hall, Lancaster Road, Preston, Lancashire, PR1 2RL NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS' NAMES AND OFFICES Lancashire County Council Election of a County Councillor for Preston Central West Division on Thursday 4 May 2017 I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them may be sent, have respectively been declared in writing to me as follows: -

Central Lancashire Open Space Assessment Report

CENTRAL LANCASHIRE OPEN SPACE ASSESSMENT REPORT FEBRUARY 2019 Knight, Kavanagh & Page Ltd Company No: 9145032 (England) MANAGEMENT CONSULTANTS Registered Office: 1 -2 Frecheville Court, off Knowsley Street, Bury BL9 0UF T: 0161 764 7040 E: [email protected] www.kkp.co.uk Quality assurance Name Date Report origination AL / CD July 2018 Quality control CMF July 2018 Client comments Various Sept/Oct/Nov/Dec 2018 Revised version KKP February 2019 Agreed sign off April 2019 Contents PART 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Report structure ...................................................................................................... 2 1.2 National context ...................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Local context ........................................................................................................... 3 PART 2: METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 4 2.1 Analysis area and population .................................................................................. 4 2.2 Auditing local provision (supply) .............................................................................. 6 2.3 Quality and value .................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Quality and value thresholds .................................................................................. -

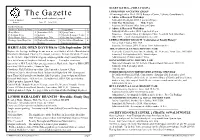

Newsletter 39

77 ` DIARY DATES – (WHAT’S ON) LFHHS IRISH ANCESTRY GROUP The Gazette All meetings held at The LFHHS Resource Centre, 2 Straits, Oswaldtwistle. § www.lfhhs-pendleandburnley.org.uk Advice & Research Workshop Pendle & Burnley Saturday 14th August 2010, 1 pm to 4.30 pm Branch Issue 39 - July 2010 § Irish War Memorials Mike Coyle Saturday 9th October 2010, 1pm to 4.30pm Inside this Issue Archive Closures & News 14 LancashireBMD 3 Programme 3 § Advice & Research Workshop Diary Dates 2 Lancashire R.O. 15 Query Corner 18 Saturday 4th December 2010, 1 pm to 4.30 pm Federation News 15 Library 3 Society Resource Centre 2 Enquiries – Shaun O'Hara, 8 Liddington Close, Newfield Park, Blackburn, Heirs House, Colne 14 News from TNA 13 Society Special offer 3 BB2 3WP. e-mail: [email protected] Heritage Open Days List 18 Probate Records in 15 Sutcliffes of Pendleton 4 LFHHS CHORLEY BRANCH "Celebration of Family History" Nelson and areas around Astley Hall, Chorley PR7 1NP Saturday 7th August 2010 11am to 5 pm Admission Free HERITAGE OPEN DAYS 9th to 12th September 2010 THE NATIONAL FAMILY HISTORY FAIR Explore the heritage buildings in our area or even further afield – Barnoldswick, Newcastle Central Premier Inn, Newbridge St., Newcastle Upon Tyne, NE1 8BS Blackburn, Blackpool, Chorley, Fleetwood, Lancaster, Nelson, Ormskirk, Preston. Saturday 11th September 2010, 10am to 4pm See the website http://www.heritageopendays.org.uk/directory/county/Lancashire Admission £3, Children under 15 free for a list of many of the places that will be open. Examples in our area DONCASTER LOCAL HISTORY FAIR Queen Street Mill Textile Museum, Queen Street, Harle Syke, Burnley BB10 2HX Doncaster Museum and Art Gallery, Chequer Road, Doncaster, DN1 2AE open Sun 12th September, 12noon to 5pm Saturday, 18th September 2010, Gawthorpe Hall, Padiham open Sun 12th September, 1pm to 4.30pm 10am to 4pm St Mary's Church, Manchester Road, Nelson and Higherford Mill, Barrowford NORTH MEOLS (SOUTHPORT) FHS ANNUAL OPEN DAY open Thurs 9th September to Sunday 12th September 11am to 4 pm on all days. -

Agenda DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE

Agenda DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Date: Wednesday, 7 October 2015 at 1:00pm Venue: Town Hall, St Annes, FY8 1LW Committee members: Councillor Trevor Fiddler (Chairman) Councillor Richard Redcliffe (Vice-Chairman) Councillors Christine Akeroyd, Peter Collins, Michael Cornah, Tony Ford JP, Neil Harvey, Kiran Mulholland, Barbara Nash, Linda Nulty, Liz Oades, Albert Pounder. Public Speaking at the Development Management Committee Members of the public may register to speak on individual planning applications, listed on the schedule at item 4: see Public Speaking at Council Meetings. PROCEDURAL ITEMS: PAGE Declarations of Interest: Declarations of interest, and the responsibility for 1 1 declaring the same, are matters for elected members. Members are able to obtain advice, in writing, in advance of meetings. This should only be sought via the Council’s Monitoring Officer. However, it should be noted that no advice on interests sought less than one working day prior to any meeting will be provided. Confirmation of Minutes: To confirm the minutes, as previously circulated, of 2 1 the meetings held on 9 September and 16 September 2015 as correct records. Substitute Members: Details of any substitute members notified in accordance 3 1 with council procedure rule 25. DECISION ITEMS: 4 Development Management Matters 3 - 139 5 List of Appeals Decided 140 6 Infrastructure Delivery Plan (The IDP) 141 - 216 The Lancashire Advanced Engineering and Manufacturing Enterprise Zone 7 217 - 269 (Warton) Local Development Order No 1 (2015) Page 1 of 269 Contact: Lyndsey Lacey - Telephone: (01253) 658504 – Email: [email protected] The code of conduct for members can be found in the council’s constitution at http://fylde.cmis.uk.com/fylde/DocumentsandInformation/PublicDocumentsandInformation.aspx © Fylde Borough Council copyright 2015 You may re-use this document/publication (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium. -

Minutes – 7 October 2015

Development Management Committee Minutes – 7 October 2015 Minutes Development Management Committee Date: Wednesday, 7 October 2015 Venue: Town Hall, St Annes Committee members: Councillor Trevor Fiddler (Chairman) Councillor Richard Redcliffe (Vice-Chairman) Councillors Christine Akeroyd, Peter Collins, Michael Cornah, Tony Ford JP, Neil Harvey, Kiran Mulholland, Barbara Nash, Linda Nulty, Liz Oades Other Council members: Councillors Maxine Chew, Paul Hayhurst, Sandra Pitman Officers: Ian Curtis, Mark Evans, Andrew Stell, Kieran Birch, Michael Eastham, Lyndsey Lacey, Stephen Smith, Matthew Taylor Members of the public: Approximately 22 members of the public were in attendance during the course of the day. Procedural Items Public Speaking at the Development Management Committee In accordance with the public speaking arrangements for the Development Management Committee, 9 members of the public addressed the committee on various applications detailed on the agenda. 1. Declarations of interest Members were reminded that any disclosable pecuniary interests should be declared as required by the Localism Act 2011 and any personal or prejudicial interests should be declared as required by the Council’s Code of Conduct for Members. Councillor Linda Nulty declared a personal and prejudicial interest in planning application no: 15/0309 relating to Mill Farm Ventures, Fleetwood Road, Medlar with Wesham and withdrew from the meeting during the consideration and voting of this item. 2. Confirmation of Minutes RESOLVED: To approve the minutes of the Development Management Committee held on 9 and 16 September 2015 as a correct record for signature by the Chairman. Development Management Committee Minutes – 7 October 2015 3. Substitute members There were no substitute members in attendance at the meeting. -

Wyre Local Plan (2011- 2031) February 2019

Title Wyre Council Wyre Local Plan (2011- 2031) February 2019 Wyre Local Plan (2011 – 2031) Blank Page 1 Wyre Local Plan (2011 – 2031) Disclaimer Contents Foreword .............................................................................................................................. 6 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Introduction 8 1.2 Preparation of the Plan 8 1.3 How the Local Plan Should be Used 10 1.4 The ‘Duty to Co-operate’ 11 1.5 Further information 11 2 Spatial Portrait and Key Issues .................................................................................. 13 2.1 Introduction 13 2.2 Spatial Characteristics 13 2.3 Population and Society 14 2.4 Housing 16 2.5 Economy 17 2.6 Environment 19 2.7 Heritage and the Built Environment 22 2.8 Infrastructure 22 2.9 Key Issues and Challenges 24 3 Vision and Objectives ................................................................................................. 28 3.1 Vision and Objectives 28 3.2 Wyre 2031 - A Vision Statement 28 3.3 Aim 29 3.4 Objectives 30 4 Local Plan Strategy ..................................................................................................... 32 Figure 4.1: Key Diagram 36 5 Strategic Policies (SP) ................................................................................................ 38 5.1 Introduction 38 5.2 Development Strategy (SP1) 38 5.3 Sustainable Development (SP2) 40 5.4 Green Belt (SP3) 41 5.5 Countryside Areas -

Spring/Summer Term 2016 Saint Aidan's Student Magazine

LWSaint Aidan’s Student Magazine Issue 3: Spring/Summer Term 2016 The Head’s Welcome Welcome to the latest edition of Live Wyre. This or Head Girl. They know that their chances would magazine has been produced completely by our depend on the letters they wrote and the views of students and once again I am really proud of what their peers and teachers, but most of all on the inter- they have done. view. At this time of year one thing is uppermost in the They faced an interview panel which might have minds of our Year 11 students: their GCSE exams. daunted many adults: Mr Smith, Headteacher, Mr They know that the results of these may have a Elwell, their Head of Year, current Head Girl and huge effect on the choices and opportunities which Head Boy Georgia Dixon and Michael Head, and are open to them in the autumn and later on in their Governors Mrs Vicky Bullen and Father Andy Shaw. lives, and I have noticed that quite rightly students They each had a short group interview with other take them more seriously each year, with hard work students and then an individual interview. Every through Year 11 supplemented by attendance at single one of them managed to overcome their revision lessons, with some even taking place in the nerves and make a good case for making them an school holidays. I am very grateful to my colleagues Officer, but in the end the panel had to choose 12 who are working so hard to help our students to Officers and 4 Senior Proctors. -

Poulton Clarkson Roadblock by James Michael Fleming © 2020

Poulton Clarkson Roadblock by James Michael Fleming © 2020 Introduction This is a summary of my research into the Poulton and Clarkson families of Lancashire. I started this project as a search for the origins of John Poulton and his wife Elizabeth Clarkson, who arrived in Sydney NSW aboard the SS Fitzjames in 1860. Having succeeded in that aim, I then extended the research to earlier generations of their families. Family historians often find information about a person’s origins from their death certificate (which usually details their parents’ names). In the case of John Poulton, his Death Certificate is no help because the informant (who was just an orderly in the hospital where he died) did not know his parent’s names. Worse still, I have not even been able to find a death certificate for his wife Elizabeth Clarkson (who left the family many years before her husband died). This situation is known by family historians as “a roadblock”, where the normal research techniques have not provided the information required to go back into earlier history. Nevertheless, there are research approaches that can sometimes find a way around a roadblock like this. In this case, I succeeded by focusing on a fellow-traveler. Jim Fleming is a retired Customs Manager and lives on Sydney’s lower north shore. He began researching his family history in 1983 and has been a member of the Society of Australian Genealogists since then. Aside from genealogy he was enjoying travelling and singing baritone in two choirs - before COVID19 interrupted those activities. Researching: Bowen, Flowerdew, Gardner, Gordon, Grady, Hanrahan, Jolliffe, Kemp, Kessey, Murphy, Poulton, Press and so many more! Website: http://jimfleming.id.au/up/index.htm I am regularly updating my website, so Like my Facebook page to keep up to date. -

Histokic Society Lancashire and Cheshire

HISTOKIC SOCIETY oj LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE. SESSION III. FEBRUARY 6th, 1851. N o . 4. The Fourth ordinary Meeting of the Session, was held at the Collegiate Institution, DAVID LAMB, Esq., in the Chair. The Minutes of the last Meeting were read and confirmed. The following Gentlemen were elected Members of the Society: John James Osborne, Mayor of Macclesfield. William Gray, Wheatfield, Bolton, Mayor of Bolton. Richard Darlington, Mayor of Wigan. The following were also elected Honorary Members : J. Yonge Akennan, Esq., Secretary of the Society of Antiquaries, London. W. B. D. D. Turnbull, Esq., Secretary of the Society of Antiquaries,- Scotland. Sir William Betham, F.S.A., M.R.I.A., of the Royal Irish Academy. C. Roach Smith, F.S.A., of the Archaeological Association. Sir John P. Boileau, Bart., V. P. of the Archfeological Institute. Philip P. Duncan, M.A., Ashmolean Society, Oxford. Rev. Professor Willis, F.R.S., Cambridge Antiquarian Society. Rev. J. Williams, M.A., Cambrian Archaeological Association. W. H. Blauuw, Esq., Sussex Arehfeological Society. Dawson Turner, F.R.S., Norfolk and Norwich Antiquarian Society. Edward Charlton, M.D., Newcastle Antiquarian Society. The following Presents to the Society were announced : From Edward Higgin, Esq., An Essay on the construction of Locks and Keys, by John Chubb, Assoc. Inst., C.E., 1851. T 52 From the Society, Journal of the Chester Architectural, Areh- ffiological, and Historic Society. Part I. to July, 1850. From John Mather, Esq. Gore's Liverpool Directory, for the years 1766, 77, 1805, 1807, 10, 13, 16, 21, (two copies), 23, 25, 27, 28 (a supplemen tary tract), 35, 37, 39, 41, 43, 45, 47, 49. -

Site Allocations Background Paper

Wyre Council Site Allocations Background Paper September 2017 Abbreviation Definition ALC Agricultural Land Classification: Grade 1 - excellent quality agricultural land Grade 2 - very good quality agricultural land Grade 3 - good to moderate quality agricultural land Subgrade 3a - good quality agricultural land Subgrade 3b - moderate quality agricultural land Grade 4 - poor quality agricultural land Grade 5 - very poor quality agricultural land AONB Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty BHS Biological Heritage Site – local wildlife sites in Lancashire. See http://www.lancashire.gov.uk/lern/site-designations/local- sites/biological-heritage-sites.aspx CfS Wyre council Call for Sites ELCLS Employment Land and Commercial Leisure Study ELS Employment Land Study EZ Enterprise Zone FP Footpath FZ Flood Zone identified by the Environment Agency. FZ1 – low probability; FZ2 – medium probability; FZ3 – high probability or functional flood plain. HRA Habitat Regulation Assessment HSE Health and Safety Executive MSA Mineral Safeguarding Areas - See the Minerals and Waste Local Plan for Lancashire MTA Minded to Approve NPPF National Planning Policy Framework OAN Objectively Assessed Need O/L Outline Planning Permission PP Planning Permission PPG Planning Practice Guidance PROW Public Right of Way Ramsar The Convention on Wetlands, called the Ramsar Convention R/M Reserved Matters Planning Permission SA Sustainability Appraisal SAC Special Areas of Conservation SFRA Strategic Flood Risk Assessment SHLAA Strategic Housing Land Availability Appraisal SHMA -

A Cultural Investment Strategy for Lancashire May 2020

Remade: A Cultural Investment Strategy for Lancashire May 2020 Remade: A Cultural Investment Strategy For Lancashire 1 Remade: A Cultural Investment Strategy For Lancashire Contents Foreword 3 Executive Summary 5 1 2030 Vision & Outcomes 7 2 Culture & Growth 9 3 Culture & Creativity in 19 Lancashire - 3.1 Cultural strengths - 3.2 Cultural weaknesses - 3.3 Cultural threats - 3.4 Cultural opportunities 4. Lancashire Cultural Investment 41 Plan - 4.1 Fit for purpose infrastructure - 4.2 Scaling-up events and festivals - 4.3 Supporting convergence - 4.4 Building capacity 5. Partnership & Delivery 49 6 Lancashire Culture Remade 52 Glossary 55 Appendices 57 References 91 2 Remade: A Cultural Investment Strategy For Lancashire FOREWORD Lancashire’s culture – a tremendous conflation of people, history, language, traditions, art and cultural assets - is central to what defines our county as a place of creativity and making, ideas and innovation. A county of stunning coastline, rich countryside and canals that cut through historic cities and industrial towns, Lancashire is a place of unique contrasts and credibility. It is home to the UK’s first mass leisure resort as well as its oldest continual festival. It originated the Spinning Jenny in the nineteenth century and the jet engine in the twentieth century, and, where once the industrial spirit and passion of its people brought cotton and textiles to the world, they now attract international renown for their research into new and emerging technologies and Michelin stars and awards for their world class food and drink. We are incredibly proud of Lancashire’s culture. As a sector, culture and the arts attract over £7 million investment from ACE, augmenting the £34 million County Council and Local Authority combined total spend on culture.