Pythagoras' Theorem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Squaring the Circle a Case Study in the History of Mathematics the Problem

Squaring the Circle A Case Study in the History of Mathematics The Problem Using only a compass and straightedge, construct for any given circle, a square with the same area as the circle. The general problem of constructing a square with the same area as a given figure is known as the Quadrature of that figure. So, we seek a quadrature of the circle. The Answer It has been known since 1822 that the quadrature of a circle with straightedge and compass is impossible. Notes: First of all we are not saying that a square of equal area does not exist. If the circle has area A, then a square with side √A clearly has the same area. Secondly, we are not saying that a quadrature of a circle is impossible, since it is possible, but not under the restriction of using only a straightedge and compass. Precursors It has been written, in many places, that the quadrature problem appears in one of the earliest extant mathematical sources, the Rhind Papyrus (~ 1650 B.C.). This is not really an accurate statement. If one means by the “quadrature of the circle” simply a quadrature by any means, then one is just asking for the determination of the area of a circle. This problem does appear in the Rhind Papyrus, but I consider it as just a precursor to the construction problem we are examining. The Rhind Papyrus The papyrus was found in Thebes (Luxor) in the ruins of a small building near the Ramesseum.1 It was purchased in 1858 in Egypt by the Scottish Egyptologist A. -

Circumference and Area of Circles 353

Circumference and 7-1 Area of Circles MAIN IDEA Find the circumference Measure and record the distance d across the circular and area of circles. part of an object, such as a battery or a can, through its center. New Vocabulary circle Place the object on a piece of paper. Mark the point center where the object touches the paper on both the object radius and on the paper. chord diameter Carefully roll the object so that it makes one complete circumference rotation. Then mark the paper again. pi Finally, measure the distance C between the marks. Math Online glencoe.com • Extra Examples • Personal Tutor • Self-Check Quiz in. 1234 56 1. What distance does C represent? C 2. Find the ratio _ for this object. d 3. Repeat the steps above for at least two other circular objects and compare the ratios of C to d. What do you observe? 4. Graph the data you collected as ordered pairs, (d, C). Then describe the graph. A circle is a set of points in a plane center radius circumference that are the same distance from a (r) (C) given point in the plane, called the center. The segment from the center diameter to any point on the circle is called (d) the radius. A chord is any segment with both endpoints on the circle. The diameter of a circle is twice its radius or d 2r. A diameter is a chord that passes = through the center. It is the longest chord. The distance around the circle is called the circumference. -

Thermodynamics of Spacetime: the Einstein Equation of State

gr-qc/9504004 UMDGR-95-114 Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State Ted Jacobson Department of Physics, University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-4111, USA [email protected] Abstract The Einstein equation is derived from the proportionality of entropy and horizon area together with the fundamental relation δQ = T dS connecting heat, entropy, and temperature. The key idea is to demand that this relation hold for all the local Rindler causal horizons through each spacetime point, with δQ and T interpreted as the energy flux and Unruh temperature seen by an accelerated observer just inside the horizon. This requires that gravitational lensing by matter energy distorts the causal structure of spacetime in just such a way that the Einstein equation holds. Viewed in this way, the Einstein equation is an equation of state. This perspective suggests that it may be no more appropriate to canonically quantize the Einstein equation than it would be to quantize the wave equation for sound in air. arXiv:gr-qc/9504004v2 6 Jun 1995 The four laws of black hole mechanics, which are analogous to those of thermodynamics, were originally derived from the classical Einstein equation[1]. With the discovery of the quantum Hawking radiation[2], it became clear that the analogy is in fact an identity. How did classical General Relativity know that horizon area would turn out to be a form of entropy, and that surface gravity is a temperature? In this letter I will answer that question by turning the logic around and deriving the Einstein equation from the propor- tionality of entropy and horizon area together with the fundamental relation δQ = T dS connecting heat Q, entropy S, and temperature T . -

Descriptive Geometry Section 10.1 Basic Descriptive Geometry and Board Drafting Section 10.2 Solving Descriptive Geometry Problems with CAD

10 Descriptive Geometry Section 10.1 Basic Descriptive Geometry and Board Drafting Section 10.2 Solving Descriptive Geometry Problems with CAD Chapter Objectives • Locate points in three-dimensional (3D) space. • Identify and describe the three basic types of lines. • Identify and describe the three basic types of planes. • Solve descriptive geometry problems using board-drafting techniques. • Create points, lines, planes, and solids in 3D space using CAD. • Solve descriptive geometry problems using CAD. Plane Spoken Rutan’s unconventional 202 Boomerang aircraft has an asymmetrical design, with one engine on the fuselage and another mounted on a pod. What special allowances would need to be made for such a design? 328 Drafting Career Burt Rutan, Aeronautical Engineer Effi cient travel through space has become an ambi- tion of aeronautical engineer, Burt Rutan. “I want to go high,” he says, “because that’s where the view is.” His unconventional designs have included every- thing from crafts that can enter space twice within a two week period, to planes than can circle the Earth without stopping to refuel. Designed by Rutan and built at his company, Scaled Composites LLC, the 202 Boomerang aircraft is named for its forward-swept asymmetrical wing. The design allows the Boomerang to fl y faster and farther than conventional twin-engine aircraft, hav- ing corrected aerodynamic mistakes made previously in twin-engine design. It is hailed as one of the most beautiful aircraft ever built. Academic Skills and Abilities • Algebra, geometry, calculus • Biology, chemistry, physics • English • Social studies • Humanities • Computer use Career Pathways Engineers should be creative, inquisitive, ana- lytical, detail oriented, and able to work as part of a team and to communicate well. -

1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Lines, and Planes

Understanding Points, 1-11-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Lines, and Planes Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Objectives Identify, name, and draw points, lines, segments, rays, and planes. Apply basic facts about points, lines, and planes. Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Vocabulary undefined term point line plane collinear coplanar segment endpoint ray opposite rays postulate Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes The most basic figures in geometry are undefined terms, which cannot be defined by using other figures. The undefined terms point, line, and plane are the building blocks of geometry. Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Points that lie on the same line are collinear. K, L, and M are collinear. K, L, and N are noncollinear. Points that lie on the same plane are coplanar. Otherwise they are noncoplanar. K L M N Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Example 1: Naming Points, Lines, and Planes A. Name four coplanar points. A, B, C, D B. Name three lines. Possible answer: AE, BE, CE Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Example 2: Drawing Segments and Rays Draw and label each of the following. A. a segment with endpoints M and N. N M B. opposite rays with a common endpoint T. T Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Check It Out! Example 2 Draw and label a ray with endpoint M that contains N. -

Machine Drawing

2.4 LINES Lines of different types and thicknesses are used for graphical representation of objects. The types of lines and their applications are shown in Table 2.4. Typical applications of different types of lines are shown in Figs. 2.5 and 2.6. Table 2.4 Types of lines and their applications Line Description General Applications A Continuous thick A1 Visible outlines B Continuous thin B1 Imaginary lines of intersection (straight or curved) B2 Dimension lines B3 Projection lines B4 Leader lines B5 Hatching lines B6 Outlines of revolved sections in place B7 Short centre lines C Continuous thin, free-hand C1 Limits of partial or interrupted views and sections, if the limit is not a chain thin D Continuous thin (straight) D1 Line (see Fig. 2.5) with zigzags E Dashed thick E1 Hidden outlines G Chain thin G1 Centre lines G2 Lines of symmetry G3 Trajectories H Chain thin, thick at ends H1 Cutting planes and changes of direction J Chain thick J1 Indication of lines or surfaces to which a special requirement applies K Chain thin, double-dashed K1 Outlines of adjacent parts K2 Alternative and extreme positions of movable parts K3 Centroidal lines 2.4.2 Order of Priority of Coinciding Lines When two or more lines of different types coincide, the following order of priority should be observed: (i) Visible outlines and edges (Continuous thick lines, type A), (ii) Hidden outlines and edges (Dashed line, type E or F), (iii) Cutting planes (Chain thin, thick at ends and changes of cutting planes, type H), (iv) Centre lines and lines of symmetry (Chain thin line, type G), (v) Centroidal lines (Chain thin double dashed line, type K), (vi) Projection lines (Continuous thin line, type B). -

A Historical Introduction to Elementary Geometry

i MATH 119 – Fall 2012: A HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION TO ELEMENTARY GEOMETRY Geometry is an word derived from ancient Greek meaning “earth measure” ( ge = earth or land ) + ( metria = measure ) . Euclid wrote the Elements of geometry between 330 and 320 B.C. It was a compilation of the major theorems on plane and solid geometry presented in an axiomatic style. Near the beginning of the first of the thirteen books of the Elements, Euclid enumerated five fundamental assumptions called postulates or axioms which he used to prove many related propositions or theorems on the geometry of two and three dimensions. POSTULATE 1. Any two points can be joined by a straight line. POSTULATE 2. Any straight line segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line. POSTULATE 3. Given any straight line segment, a circle can be drawn having the segment as radius and one endpoint as center. POSTULATE 4. All right angles are congruent. POSTULATE 5. (Parallel postulate) If two lines intersect a third in such a way that the sum of the inner angles on one side is less than two right angles, then the two lines inevitably must intersect each other on that side if extended far enough. The circle described in postulate 3 is tacitly unique. Postulates 3 and 5 hold only for plane geometry; in three dimensions, postulate 3 defines a sphere. Postulate 5 leads to the same geometry as the following statement, known as Playfair's axiom, which also holds only in the plane: Through a point not on a given straight line, one and only one line can be drawn that never meets the given line. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

Geometry Course Outline

GEOMETRY COURSE OUTLINE Content Area Formative Assessment # of Lessons Days G0 INTRO AND CONSTRUCTION 12 G-CO Congruence 12, 13 G1 BASIC DEFINITIONS AND RIGID MOTION Representing and 20 G-CO Congruence 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Combining Transformations Analyzing Congruency Proofs G2 GEOMETRIC RELATIONSHIPS AND PROPERTIES Evaluating Statements 15 G-CO Congruence 9, 10, 11 About Length and Area G-C Circles 3 Inscribing and Circumscribing Right Triangles G3 SIMILARITY Geometry Problems: 20 G-SRT Similarity, Right Triangles, and Trigonometry 1, 2, 3, Circles and Triangles 4, 5 Proofs of the Pythagorean Theorem M1 GEOMETRIC MODELING 1 Solving Geometry 7 G-MG Modeling with Geometry 1, 2, 3 Problems: Floodlights G4 COORDINATE GEOMETRY Finding Equations of 15 G-GPE Expressing Geometric Properties with Equations 4, 5, Parallel and 6, 7 Perpendicular Lines G5 CIRCLES AND CONICS Equations of Circles 1 15 G-C Circles 1, 2, 5 Equations of Circles 2 G-GPE Expressing Geometric Properties with Equations 1, 2 Sectors of Circles G6 GEOMETRIC MEASUREMENTS AND DIMENSIONS Evaluating Statements 15 G-GMD 1, 3, 4 About Enlargements (2D & 3D) 2D Representations of 3D Objects G7 TRIONOMETRIC RATIOS Calculating Volumes of 15 G-SRT Similarity, Right Triangles, and Trigonometry 6, 7, 8 Compound Objects M2 GEOMETRIC MODELING 2 Modeling: Rolling Cups 10 G-MG Modeling with Geometry 1, 2, 3 TOTAL: 144 HIGH SCHOOL OVERVIEW Algebra 1 Geometry Algebra 2 A0 Introduction G0 Introduction and A0 Introduction Construction A1 Modeling With Functions G1 Basic Definitions and Rigid -

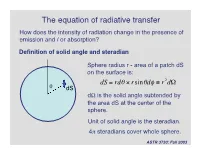

The Equation of Radiative Transfer How Does the Intensity of Radiation Change in the Presence of Emission and / Or Absorption?

The equation of radiative transfer How does the intensity of radiation change in the presence of emission and / or absorption? Definition of solid angle and steradian Sphere radius r - area of a patch dS on the surface is: dS = rdq ¥ rsinqdf ≡ r2dW q dS dW is the solid angle subtended by the area dS at the center of the † sphere. Unit of solid angle is the steradian. 4p steradians cover whole sphere. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Definition of the specific intensity Construct an area dA normal to a light ray, and consider all the rays that pass through dA whose directions lie within a small solid angle dW. Solid angle dW dA The amount of energy passing through dA and into dW in time dt in frequency range dn is: dE = In dAdtdndW Specific intensity of the radiation. † ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Compare with definition of the flux: specific intensity is very similar except it depends upon direction and frequency as well as location. Units of specific intensity are: erg s-1 cm-2 Hz-1 steradian-1 Same as Fn Another, more intuitive name for the specific intensity is brightness. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Simple relation between the flux and the specific intensity: Consider a small area dA, with light rays passing through it at all angles to the normal to the surface n: n o In If q = 90 , then light rays in that direction contribute zero net flux through area dA. q For rays at angle q, foreshortening reduces the effective area by a factor of cos(q). -

Epicurus and the Epicureans on Socrates and the Socratics

chapter 8 Epicurus and the Epicureans on Socrates and the Socratics F. Javier Campos-Daroca 1 Socrates vs. Epicurus: Ancients and Moderns According to an ancient genre of philosophical historiography, Epicurus and Socrates belonged to distinct traditions or “successions” (diadochai) of philosophers. Diogenes Laertius schematizes this arrangement in the following way: Socrates is placed in the middle of the Ionian tradition, which starts with Thales and Anaximander and subsequently branches out into different schools of thought. The “Italian succession” initiated by Pherecydes and Pythagoras comes to an end with Epicurus.1 Modern views, on the other hand, stress the contrast between Socrates and Epicurus as one between two opposing “ideal types” of philosopher, especially in their ways of teaching and claims about the good life.2 Both ancients and moderns appear to agree on the convenience of keeping Socrates and Epicurus apart, this difference being considered a fundamental lineament of ancient philosophy. As for the ancients, however, we know that other arrangements of philosophical traditions, ones that allowed certain connections between Epicureanism and Socratism, circulated in Hellenistic times.3 Modern outlooks on the issue are also becoming more nuanced. 1 DL 1.13 (Dorandi 2013). An overview of ancient genres of philosophical history can be seen in Mansfeld 1999, 16–25. On Diogenes’ scheme of successions and other late antique versions of it, see Kienle 1961, 3–39. 2 According to Riley 1980, 56, “there was a fundamental difference of opinion concerning the role of the philosopher and his behavior towards his students.” In Riley’s view, “Epicurean criticism was concerned mainly with philosophical style,” not with doctrines (which would explain why Plato was not as heavily attacked as Socrates). -

Area of Polygons and Complex Figures

Geometry AREA OF POLYGONS AND COMPLEX FIGURES Area is the number of non-overlapping square units needed to cover the interior region of a two- dimensional figure or the surface area of a three-dimensional figure. For example, area is the region that is covered by floor tile (two-dimensional) or paint on a box or a ball (three- dimensional). For additional information about specific shapes, see the boxes below. For additional general information, see the Math Notes box in Lesson 1.1.2 of the Core Connections, Course 2 text. For additional examples and practice, see the Core Connections, Course 2 Checkpoint 1 materials or the Core Connections, Course 3 Checkpoint 4 materials. AREA OF A RECTANGLE To find the area of a rectangle, follow the steps below. 1. Identify the base. 2. Identify the height. 3. Multiply the base times the height to find the area in square units: A = bh. A square is a rectangle in which the base and height are of equal length. Find the area of a square by multiplying the base times itself: A = b2. Example base = 8 units 4 32 square units height = 4 units 8 A = 8 · 4 = 32 square units Parent Guide with Extra Practice 135 Problems Find the areas of the rectangles (figures 1-8) and squares (figures 9-12) below. 1. 2. 3. 4. 2 mi 5 cm 8 m 4 mi 7 in. 6 cm 3 in. 2 m 5. 6. 7. 8. 3 units 6.8 cm 5.5 miles 2 miles 8.7 units 7.25 miles 3.5 cm 2.2 miles 9.