Rootlessness” in a Suburban Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

These Locations Are Available for Use Now | Estas Ubicaciones Ya Están Desponibles These Locations Will Be Available for Use By

Montgomery County - Ballot Drop Off Locations for the 2020 Presidential General Election | Condado de Montgomery – Ubicaciones de entrega de papeletas para las elecciones generals presidenciales de 2020 These locations are available for use now | Estas ubicaciones ya están desponibles Montgomery County Board of Elections 18753 North Frederick Avenue Gaithersburg, MD 20879 (Drive-up Box) City of Rockville 111 Maryland Avenue Rockville, MD 20850 (City Hall Parking Lot | Estacionamiento de la Municipalidad) (Drive-up Box) Executive Office Building 101 Monroe Street Rockville, MD 20850 These locations will be available for use by September 28th - 30th | Estas ubicaciones estarán disponibles para su uso entre el 28 al 30 de septiembre Activity Center at Bohrer Park 506 South Frederick Avenue Gaithersburg, MD 20877 Clarksburg High School 22500 Wims Road Clarksburg, MD 20871 Col. Zadok Magruder High School 5939 Muncaster Mill Road Rockville, MD 20855 Damascus Community Recreation Center 25520 Oak Drive Damascus, MD 20872 Germantown Community Recreation Center 18905 Kingsview Road Germantown, MD 20874 Jane E. Lawton Community Recreation Center 4301 Willow Lane Chevy Chase, MD 20815 Marilyn J. Praisner Community Recreation Center 14906 Old Columbia Pike Burtonsville, MD 20866 Mid-County Community Recreation Center 2004 Queensguard Road Silver Spring, MD 20906 Montgomery Blair High School 51 University Boulevard East Silver Spring, MD 20901 Montgomery Co. Conference Center Marriott Bethesda North 5967 Executive Boulevard North Bethesda, MD 20852 -

Paint Branch High School Academy of Science and Media

Paint Branch High School Academy of Science and Media 14121 Old Columbia Pike, Burtonsville, MD 20866-1799 301-388-9920 FAX: 301-989-6095 www.montgomeryschoolsmd.org/schools/paintbranchhs THE SCHOOL Paint Branch High School, a Montgomery County, MD public school, is located 30 miles from Washington, DC, in a community that has a blend of both urban and small town features. Originally opened in the fall of 1969, a completely modernized Paint Branch opened on August 27, 2012. Paint Branch is a part of the Northeast Consortium of Schools in which students may choose to attend the school. Paint Branch maintains a comprehensive four-year curriculum including Advanced Placement courses (AP), the Honors Program (H), and Special Education programs. Additionally, we offer an innovative whole-school Signature Program which enhances and extends the high school curriculum. Paint Branch serves a socio-economically and ethnically diverse community with students from 80 different countries. The school is accredited by the Maryland State Department of Education. The Signature Program is comprised of several themes : Science - provides a wide range of science and health occupation courses, programs and activities. Paint Branch offers advanced courses in many subjects including Medical Careers, Molecular Biology, Engineering Science, Environmental Science, Biotechnology, Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences as well as a Food Science Program, specializing in Professional Restaurant Management. Media - provides a wide range of media electives and required courses and activities that infuse media skills and concepts. In 2003, Paint Branch became one of four county schools to attain recognition as a member of the Academy of Finance by offering an academically rigorous college-preparatory program from the National Academy Foundation that encourages high school students to take courses in financial studies and related disciplines. -

Scholarship Award Winners

ACTION Office of the Superintendent of Schools MONTGOMERY COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS Rockville, Maryland May 8, 2018 MEMORANDUM To: Members of the Board of Education From: Jack R. Smith, Superintendent of Schools Subject: Recognition of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Scholarship Award Winners WHEREAS, The Montgomery County Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People awarded, at its annual Freedom Fund Dinner, seventeen $1,000 scholarships and one $1,200 scholarship to Montgomery County Public Schools students; and WHEREAS, The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People selected Steadfast & Immovable as the theme of its forty-third Freedom Fund Dinner, held on Sunday, May 6, 2018, to recognize Black or African American students for their positive contributions to our schools and community; and WHEREAS, Montgomery County recognizes and celebrates its students’ community service achievements that make a difference to our county, our state, and our country; and WHEREAS, The Montgomery County Board of Education takes great pride that Montgomery County Public Schools honors the many contributions of Black or African American students; now therefore be it Resolved, That on behalf of the superintendent of schools, staff members, students, and parents/guardians of Montgomery County Public Schools, the members of the Montgomery County Board of Education congratulate this year’s National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Scholarship Awards winners: Fatim B. Bagayoko, Paint Branch High School Phylicia R. Cooper, James Hubert Blake High School Meghan M. Curtis, Damascus High School Mariam T. Deme, Paint Branch High School Laurie C. C. France, Paint Branch High School Amber L. -

Fy 2016 Annual Report

A N N U A L REPORT FY 2016 D e a r F r i e n d s , BOARD OF DIRECTORS What a busy and productive Fiscal Year 2016 it has been for Manna, both with respect to service and strategy! Chair: Carla Krivak Administrative Patent Judge Manna Food Center launched a three year planning process, analyzing the Patent Trial and Appeal Board feedback of stakeholders and trends in our community. Throughout that process, Chair Elect: Davis Bradley Tyner we continued delivering high quality services and nutritious food to 32,756 Senior Strategic Advisor Public Company Accounting individuals through a network of two dozen distribution sites. Thanks to 55 Oversight Board community partners at 60 MCPS elementary schools, Manna’s Smart Sacks Past Chair: Nancy Williams program supported the academic achievement of more than 2,490 students Vice President through good nutrition and “Smart Sacks Food Facts.” Around the County we DecisionPath Consulting conducted 94 classes to share skills for shopping and cooking on a budget. Treasurer: Nina MojiriAzad Assistant General Counsel Public Company Accounting However, statistics only tell a partial story. Manna, with the help of our Oversight Board partners, has increased the Maryland Food Supplement Program (SNAP) for Julie Heatherly seniors, created a new outreach office in Silver Spring, and has had great IT Consultant success with the innovative Community Food Rescue network. Yuchi Huang A huge thank you to our supporters and our many volunteers, who helped make Community Volunteer these accomplishments possible. Please continue the fight hunger with us. We Jeffrey Lewis District Director cannot do this work without your support! As we look to the future, we recognize Giant Food/Ahold our community faces many food security challenges, especially regarding seniors, people with disabilities, and the working poor. -

Election Day Vote Centers Each Vote Center Will Be Open November 3, 2020 from 7 Am to 8 Pm

2020 General Election Election Day Vote Centers Each vote center will be open November 3, 2020 from 7 am to 8 pm. Voters in line at 8 pm will be able to vote. County Location Address City State Zip Allegany Allegany County Office Complex, Room 100 701 Kelly Road Cumberland MD 21502 Allegany Allegany High School 900 Seton Drive Cumberland MD 21502 Allegany Flintstone Volunteer Fire Dept 21701 Flintstone Drive NE Flintstone MD 21530 Allegany Fort Hill High School 500 Greenway Avenue Cumberland MD 21502 Allegany Mountain Ridge High School 100 Dr. Nancy S Grasmick Lane Frostburg MD 21532 Allegany Westmar Middle School 16915 Lower Georges Creek Road SW Lonaconing MD 21539 Anne Arundel Annapolis High School 2700 Riva Road Annapolis MD 21401 Anne Arundel Arnold Elementary School 95 E Joyce Lane Arnold MD 21012 Anne Arundel Arundel High School 1001 Annapolis Road Gambrills MD 21054 Anne Arundel Bates Middle School 701 Chase Street Annapolis MD 21401 Anne Arundel Broadneck High School 1265 Green Holly Drive Annapolis MD 21409 Anne Arundel Brock Bridge Elementary School 405 Brock Bridge Road Laurel MD 20724 Anne Arundel Brooklyn Park Middle School 200 Hammonds Lane Baltimore MD 21225 Anne Arundel Chesapeake High School 4798 Mountain Road Pasadena MD 21122 Anne Arundel Chesapeake Science Point Charter School 7321 Parkway Drive South Hanover MD 21076 Anne Arundel Corkran Middle School 7600 Quarterfield Road Glen Burnie MD 21061 Anne Arundel Crofton Elementary School 1405 Duke of Kent Drive Crofton MD 21114 Anne Arundel Crofton Middle School 2301 -

Division 4 Championships - 2/2/2019 Results

Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 7.0 - 11:51 PM 2/2/2019 Page 1 Division 4 Championships - 2/2/2019 Results Event 1 Boys 200 Yard Medley Relay MCPS: 1:33.99 # 2018 Quince Orchard 1:52.99 MET Metros Team Relay Finals Time Points 1 Springbrook High School A 1:47.80 MET 40 1) Iscoa, Nicolas 2) Dietrich, Joseph 3) Gruner, Ryan 4) Taylor, Luke 2 Seneca Valley-MD A 1:50.04 MET 34 1) Vilbig, Umi 15 2) McCabe, Isaac 3) Cunningham, Walter 4) Crowe, Parker 16 3 Northwood-MD A 1:51.20 MET 32 1) Colson, Sean 14 2) Hofmann, Jakob 14 3) Gondi, max 15 4) Werber, Jason 4 Wheaton High School A 1:56.00 30 1) Bearman, Josh 2) Mueller, Matthew 3) Cerron, Cody 4) Smith, Fletcher 5 Paint Branch High School A 1:57.46 28 1) Liewehr, Adam 2) Garavaglia, Daniel 3) Sletten, Alexander 4) Tran, Chris 6 John F. Kennedy-MD A 2:07.56 26 1) Virga, Ian 15 2) Hahn, David 17 3) Martinez, Eduardo 15 4) Liborio, Cristopher 15 7 Watkins Mill High School-MD A 2:10.28 1) Ariel Cruz, Selvin 2) Crews, Christopher 3) Guilds, Brennan 4) Jayalal, Vimukthi Event 2 Girls 200 Yard Medley Relay MCPS: 1:45.21 # 2013 Wootton 2:05.99 MET Metros Team Relay Finals Time Points 1 Wheaton High School A 1:54.49 MET 40 1) Daniel, Amaya 2) Johnson, Gabby 3) Bowrin, Nia 4) Kabeya, Marie-Elizabeth 2 Springbrook High School A 1:59.75 MET 34 1) Bauer, Mollie 2) Lakey, Alexis 3) Davis, Ayana 4) Sanidad, Brianna 14 3 Seneca Valley-MD A 2:04.16 MET 32 1) McCabe, Illy R 16 2) Badger, Lauren 3) Currier, Emma 4) Allison, Abbie 16 4 Northwood-MD A 2:11.06 30 1) Laduca, Alexandra 14 2) Stumphauzer, Lorelei 15 3) ng, Hope 15 4) Brennan, Madeleine 15 5 John F. -

I See ME in ALL 3! WHERE ARE RECENT CONSORTIUM GRADUATES NOW?*

3 Great Schools! 3 Great Choices! School Years 2017–2019 MONTGOMERY COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS NORTHEAST CONSORTIUM HIGH SCHOOLS Information about the Northeast Consortium (NEC) Choice Process and Signature Programs • BLAKE • PAINT BRANCH • SPRINGBROOK I see ME in ALL 3! WHERE ARE RECENT CONSORTIUM GRADUATES NOW?* Adelphi University Duke University Lynchburg College Ringling College of Art and Design University of Maine Albright College Dunwoody College of Technology Lynn University Rochester Institute of Technology University of Maryland, Baltimore County Allegany College of Maryland Duquesne University Macalester College Rutgers University, New Brunswick University of Maryland, College Park Allegheny College Earlham College Make Up Forever Academy, New York Saint Anselm College University of Maryland, Eastern Shore AMDA—The American Musical and East Carolina University Manhattanville College Saint Joseph’s University University of Maryland University College Dramatic Academy Eastern University Marshall University Salisbury University University of Massachusetts, Amherst American Academy of Dramatic Arts Eckerd College Mary Baldwin College San Diego State University University of Miami American University Elizabeth City State University Maryland Institute College of Art Santa Barbara City College University of Michigan Anne Arundel Community College Elizabethtown College Marymount University Sarah Lawrence College University of Minnesota, Twin Cities Antioch College Elon University Massachusetts Institute of Technology Savannah College of -

ACTION Office of the Superintendent of Schools MONTGOMERY

ACTION Office of the Superintendent of Schools MONTGOMERY COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS Rockville, Maryland July 15, 2021 MEMORANDUM To: Members of the Board of Education From: Monifa B. McKnight, Interim Superintendent of Schools Subject: Retirement of Montgomery County Public Schools Personnel WHEREAS, The persons on the attached list are retiring or have retired from Montgomery County Public Schools; and WHEREAS, Each person, through outstanding performance of duties and dedication to the education of our youth, has made a significant contribution to the school system, which is worthy of special commendation; now therefore be it Resolved, That the members of the Board of Education express their sincere appreciation to each person for faithful service to the school system and to the children of the county, and also extend to each one best wishes for the future; and be it further Resolved, That a copy of this resolution is published on the Employee and Retiree Service Center web page and available to each retiree. MBM:DKM:KT:sy Attachment Name and Latest Assignment Montgomery County Years of Service Mrs. Linda M. Abadia Bus Route Supervisor Department of Transportation, effective, 6/1/2021 15.2 Ms. Joy A. Abiodun Teacher Newport Mill Middle School, effective, 7/1/2021 17.7 Mrs. Laura D. Acuna Paraeducator, Special Education Damascus High School, effective, 2/1/2021 30.0 Mr. Joseph Addo Building Service Assistant Manager IV Shift 2 Paint Branch High School, effective, 2/1/2021 27.4 Mr. Ohannes A. Aghguiguian Bus Operator I Department of Transportation, effective, 7/1/2021 15.8 Mr. Luis G. -

Maryland Players Selected in Major League Baseball Free-Agent Drafts

Maryland Players selected in Major League Baseball Free-Agent Drafts Compiled by the Maryland State Association of Baseball Coaches Updated 16 February 2021 Table of Contents History .............................................................................. 2 MLB Draft Selections by Year ......................................... 3 Maryland First Round MLB Draft Selections ................. 27 Maryland Draft Selections Making the Majors ............... 28 MLB Draft Selections by Maryland Player .................... 31 MLB Draft Selections by Maryland High School ........... 53 MLB Draft Selections by Maryland College .................. 77 1 History Major League Baseball’s annual First-Year Player Draft began in June, 1965. The purpose of the draft is to assign amateur baseball players to major league teams. The draft order is determined based on the previous season's standings, with the team possessing the worst record receiving the first pick. Eligible amateur players include graduated high school players who have not attended college, any junior or community college players, and players at four-year colleges and universities three years after first enrolling or after their 21st birthdays (whichever occurs first). From 1966-1986, a January draft was held in addition to the June draft targeting high school players who graduated in the winter, junior college players, and players who had dropped out of four-year colleges and universities. To date, there have been 1,170 Maryland players selected in the First-Year Player Drafts either from a Maryland High School (337), Maryland College (458), Non-Maryland College (357), or a Maryland amateur baseball club (18). The most Maryland selections in a year was in 1970 (38) followed by 1984 (37) and 1983 (36). The first Maryland selection was Jim Spencer from Andover High School with the 11th overall selection in the inaugural 1965 June draft. -

THE MONTGOMERY COUNTY SENTINEL FEBRUARY 8, 2018 EFLECTIONS the Montgomery County Sentinel, Published Weekly by Berlyn Inc

2015, 2016 MDDC News Organization of the Year! Celebrating 162 years of service! Vol. 163, No. 33 • 50¢ SINCE 1855 February 8 - February 14, 2018 TODAY’S GAS PRICE “Disappointed” $2.65 per gallon Federation confronts school system over sex abuse cases Last Week “I am extremely disappointed According to Johnson, Smith’s members demanding he comment $2.65 per gallon By Suzanne Pollak @suzannepollak that Dr. Smith was treated disre- attendance at the Jan. 8 meeting – on a resolution the Federation A month ago spectfully by audience participants, which had an announced topic of passed late last year relating to child $2.57 per gallon Montgomery County Public who were misguided about the ap- “What’s in the MCPS Fiscal Year abuse and neglect and concerns of Schools officials are up in arms fol- proved agenda for the meeting,” 2019 Operating Budget?” – was se- how much money the District was A year ago lowing a contentious meeting of the MCPS Chief of Staff Henry Johnson cured in August of last year after spending on legal settlements. $2.34 per gallon Montgomery County Civic Federa- wrote in a letter to MCCF president Smith was invited to discuss the “We were aware of the resolu- tion last month, during which audi- AVERAGE PRICE PER GALLON OF Jim Zepp. “In fairness to the super- MCPS budget around the time it tion,” but not that it would be a top- UNLEADED REGULAR GAS IN ence members angrily confronted intendent, the MCCF leadership would be considered by the County ic of discussion for the Superinten- MARYLAND/D.C. -

Board of Education Meeting: May 27, 1986

APPROVED Rockville, Maryland 25-1986 May 27, 1986 The Board of Education of Montgomery County met in regular session at the Carver Educational Services Center, Rockville, Maryland, on Tuesday, May 27, 1986, at 8:15 p.m. ROLL CALL Present: Dr. James E. Cronin, President in the Chair Mrs. Sharon DiFonzo Mr. Blair G. Ewing Mr. John D. Foubert Mrs. Marilyn J. Praisner Dr. Robert E. Shoenberg Mrs. Mary Margaret Slye Absent: Dr. Jeremiah Floyd Others Present: Dr. Wilmer S. Cody, Superintendent of Schools Dr. Harry Pitt, Deputy Superintendent Dr. Robert S. Shaffner, Executive Assistant Mr. Thomas S. Fess, Parliamentarian Mr. Eric Steinberg, Board Member-elect Re: ANNOUNCEMENT Dr. Cronin announced that Dr. Floyd was out of town and sent his regrets. RESOLUTION NO. 292-86 Re: BOARD AGENDA - MAY 27, 1986 On recommendation of the superintendent and on motion of Mrs. Praisner seconded by Mr. Foubert, the following resolution was adopted unanimously: RESOLVED, That the Board of Education approve its agenda for May 27, 1986, with the deletion of the item on Reorganization of the Department of Management Information and Computer Services. RESOLUTION NO. 293-86 Re: PROCUREMENT CONTRACTS OVER $25,000 On recommendation of the superintendent and on motion of Mrs. Praisner seconded by Mr. Foubert, the following resolution was adopted unanimously: WHEREAS, Funds have been budgeted for the purchase of equipment, supplies, and contractual services; now therefore be it RESOLVED, That having been duly advertised, the contracts be awarded to the low bidders meeting specifications as shown for the bids as follows: NAME OF VENDOR(S) DOLLAR VALUE OF CONTRACTS 85-13 Software for Automated Payroll Systems Integral Systems, Inc. -

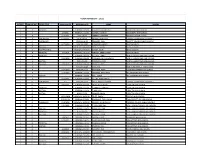

2020-21 Membership List for Website 3-1-21

MSADA MEMBERSHIP - 3/1/21 DISTRICT SUB DISTRICT OTHER TITLE NIAAA as of YR MSADA as of YR NAME SCHOOL 1 A PRINCIPAL RENEWAL 1/21/21 KUHANECK, DR MICHAEL BOONSBORO HIGH SCHOOL 1 A 2/8/2021 RENEWAL 1/21/21 LOWERY, SUSAN M BOONSBORO HIGH SCHOOL 1 A 2/10/2021 NEW 1/8/21 JARRETT, JONATHAN BRUNSWICK HIGH SCHOOL 1 A SUPERVISOR 1/19/2021 NEW 1/8/21 BROWN, JOHN (RAA) CARROLL COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS 1 A SUPERVISOR RENEWAL 4/20 EDWARDS, PAUL GARRETT COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS 1 A 9/17/2020 NEW 9/2/2020 BURGENER, SHAWN GRACE ACDEMY 1 A ASST AD RENEWAL 9/2/2020 HUNT, STEPHEN GRACE ACDEMY 1 A ASST PRINCIPAL RENEWAL 9/2/2020 SMOOT, KEVIN GRACE ACDEMY 1 A PRINCIPAL 9/2/2020 RENEWAL 9/2/2020 WHITLEY, GREG (CMAA) GRACE ACDEMY 1 A PRINCIPAL RENEWAL 10/6/20 ALESHIRE, JAMES NORTH HAGERSTOWN HIGH SCHOOL 1 A 10/6/2020 RENEWAL 10/6/20 CUNNINGHAM, DAN (CMAA) NORTH HAGERSTOWN HIGH SCHOOL 1 A ASST AD NEW 10/6/20 ROBINSON, ADAM NORTH HAGERSTOWN HIGH SCHOOL 1 A ASST AD 3/1/2020 RENEWAL 10/6/20 WEAVER, RALPH NORTH HAGERSTOWN HIGH SCHOOL 1 A RENEWAL 4/20 CARR, PHIL NORTHERN GARRETT HIGH SCHOOL 1 A 2/27/2020 RENEWAL 2/20 REDINGER, MATT SOUTHERN GARRETT HIGH SCHOOL 1 A 12/3/2020 RENEWAL 12/3/20 CRABTREE, EMILY (RAA) WILLIAMSPORT HIGH SCHOOL 1 A ASST AD RENEWAL 12/3/20 NOLL, SCOTT WILLIAMSPORT HIGH SCHOOL 1 A 2/22/2021 RENEWAL 2/22/21 ULLERY, TODD (CMAA) 1 B SUPERVISOR LIFE RENEWAL 3/20 DUFFY, MICHAEL (CMAA) CARROLL COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS 1 B 2/22/2021 RENEWAL 2/22/21 BRUCK, KEITH (CAA) CATOCTIN HIGH SCHOOL 1 B PRINCIPAL RENEWAL 2/22/21 CLEMENTS, JENNIFER CATOCTIN HIGH SCHOOL