The Political Obligation of a Citizen, 52 Case W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Hiki) Space: Sharing a Computer in a First-Grade Classroom

I HIKI) SPACE: SHARING A COMPUTER IN A FIRST-GRADE CLASSROOM BY XIAO-HUI CHRISTINE WANG B.Ed., Beijing Normal University, 1992 M.Ed., Beijing Normal University. 1995 THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2003 llrbana. Illinois 3 id yQjiko l NIVERSII V OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN GRADUATE COLLEGE May, 2003 date WE HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS BY Xiao-Hui Christine Wang . ^ ™ Third Space: Sharing a Computer in a First-Grade Classroom E N T I T L E D __________________________________________ BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF P °ctor Philosophy______________________________________ A- ---------- Director of Thesis Research Head of Department tRequired for doctor’s decree hut not for master s. 0-5 1 7 Copyright by Xiao-Hui Christine Wang, 2003 ABSTRACT Drawing primarily upon sociocultural perspectives and space theory, I propose a transactional model of Third Space construction to investigate young children’s spontaneous group game-plaving at a classroom computer, which is often misjudged as chaos, a waste ot time or a system design problem. A school year-long ethnographic stud\ was conducted in a first-grade classroom at a public school located in a Midwest town. 1 he data sources included videos, field notes, interviews and artifacts. The interaction analysis approach and grounded theory approach were applied to the research design, field work and data analysis. I he results indicate that when children spontaneously form groups around a classroom computer, highly complex and sophisticated patterns of social behavior emerge. -

ENDER's GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third

ENDER'S GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third "I've watched through his eyes, I've listened through his ears, and tell you he's the one. Or at least as close as we're going to get." "That's what you said about the brother." "The brother tested out impossible. For other reasons. Nothing to do with his ability." "Same with the sister. And there are doubts about him. He's too malleable. Too willing to submerge himself in someone else's will." "Not if the other person is his enemy." "So what do we do? Surround him with enemies all the time?" "If we have to." "I thought you said you liked this kid." "If the buggers get him, they'll make me look like his favorite uncle." "All right. We're saving the world, after all. Take him." *** The monitor lady smiled very nicely and tousled his hair and said, "Andrew, I suppose by now you're just absolutely sick of having that horrid monitor. Well, I have good news for you. That monitor is going to come out today. We're going to just take it right out, and it won't hurt a bit." Ender nodded. It was a lie, of course, that it wouldn't hurt a bit. But since adults always said it when it was going to hurt, he could count on that statement as an accurate prediction of the future. Sometimes lies were more dependable than the truth. "So if you'll just come over here, Andrew, just sit right up here on the examining table. -

Winter 2020 Film Calendar

National Gallery of Art Film Winter 20 Special Events 11 Abbas Kiarostami: Early Films 19 Checkerboard Films on the American Arts: Recent Releases 27 Displaced: Immigration Stories 31 African Legacy: Francophone Films 1955 to 2019 35 An Armenian Odyssey 43 Hyenas p39 Winter 2020 opens with the rarely seen early work of Abbas Kiarostami, shown as part of a com- plete retrospective of the Iranian master’s legacy screening in three locations in the Washington, DC, area — the AFI Silver Theatre, the Freer Gallery of Art, and the National Gallery of Art. A tribute to Check- erboard Film Foundation’s ongoing documentation of American artists features ten of the foundation’s most recent films. Displaced: Immigration Stories is organized in association with Richard Mosse: Incom- ing and comprises five events that allow audiences to view the migrant crisis in Europe and the United States through artists’ eyes. African Legacy: Franco- phone Films 1955 to 2019 celebrates the rich tradition of filmmaking in Cameroon, Mauritania, Ivory Coast, Senegal, and Niger, including filmmakers such as Med Hondo, Timité Bassori, Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, Ousmane Sembène, Djibril Diop Mambéty, and Moustapha Alassane as well as new work by contemporary Cameroonian artist Rosine Mbakam. An Armenian Odyssey, organized jointly with Post- Classical Ensemble, the Embassy of Armenia, the National Cinema Center of Armenia, and the Freer Gallery, combines new films and recent restorations, including works by Sergei Parajanov, Kevork Mourad, Hamo Bek-Nazaryan, and Rouben Mamoulian, as well as musical events at Washington National Cathedral. The season also includes a number of special events and lectures; filmmaker presentations with Rima Yamazaki and William Noland; and recent documentaries such as Cunningham; Leaving Home, Coming Home: A Portrait of Robert Frank; Museum Town; The Hottest August; Architecture of Infinity; and It Will Be Chaos. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

British Film Institute Report & Financial Statements 2006

British Film Institute Report & Financial Statements 2006 BECAUSE FILMS INSPIRE... WONDER There’s more to discover about film and television British Film Institute through the BFI. Our world-renowned archive, cinemas, festivals, films, publications and learning Report & Financial resources are here to inspire you. Statements 2006 Contents The mission about the BFI 3 Great expectations Governors’ report 5 Out of the past Archive strategy 7 Walkabout Cultural programme 9 Modern times Director’s report 17 The commitments key aims for 2005/06 19 Performance Financial report 23 Guys and dolls how the BFI is governed 29 Last orders Auditors’ report 37 The full monty appendices 57 The mission ABOUT THE BFI The BFI (British Film Institute) was established in 1933 to promote greater understanding, appreciation and access to fi lm and television culture in Britain. In 1983 The Institute was incorporated by Royal Charter, a copy of which is available on request. Our mission is ‘to champion moving image culture in all its richness and diversity, across the UK, for the benefi t of as wide an audience as possible, to create and encourage debate.’ SUMMARY OF ROYAL CHARTER OBJECTIVES: > To establish, care for and develop collections refl ecting the moving image history and heritage of the United Kingdom; > To encourage the development of the art of fi lm, television and the moving image throughout the United Kingdom; > To promote the use of fi lm and television culture as a record of contemporary life and manners; > To promote access to and appreciation of the widest possible range of British and world cinema; and > To promote education about fi lm, television and the moving image generally, and their impact on society. -

The Political Obligation of a Citizen

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 52 Issue 3 Article 3 2002 Ethics in the Shadow of the Law: The Political Obligation of a Citizen Robert P. Lawry Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert P. Lawry, Ethics in the Shadow of the Law: The Political Obligation of a Citizen, 52 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 655 (2002) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol52/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. ARTICLE ETHICS IN THE SHADOW OF THE LAW: THE POLITICAL OBLIGATION OF A CITIZEN Robert P. Lawr9 INTRODUCTION This article is a series of meditations on texts. The focus is on the moral quandry a citizen faces when confronted with what he or she perceives to be an unjust or immoral law or policy, emanating from the State in which that citizen has membership. As such, it is a con- tribution to the rich literature of political obligation. It joins the long debate in jurisprudence and political and legal theory over the citi- zen's "obligation to obey the law," or "fidelity to law."1 It joins that debate obliquely, however, not by trying to argue philosophically for one particular theory of political obligation, but by reflecting on inter- esting and historically important texts in that literature. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 0120660 A study of strategy use by two emergent readers in a one-to-one tutorial setting Frasier, Dianne Farrell, Ph.D. -

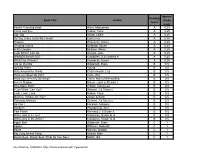

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx. -

Janus Films Presents

JANUS FILMS PRESENTS NEW 35MM PRINT! http://www.janusfilms.com/closeup Director: Abbas Kiarostami JANUS FILMS Country: Iran Brian Belovarac Year: 1990 Ph: 212-756-8761 Run time: 97 minutes [email protected] Color / 1.37 / Mono CLOSE-UP SYNOPSIS Internationally revered Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami has created some of the most inventive and transcendent cinema of the last thirty years, and Close- Up is his most radical, brilliant work. This fiction-documentary hybrid uses a real- life sensational event—a young man arrested on charges that he fraudulently impersonated well-known filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf—as the basis for a stunning, multi-layered investigation into movies, identity, artistic creation, and life itself. With its universal themes and fascinating narrative knots, Close-Up continues to resonate with viewers around the world. CLOSE-UP ABBAS KIAROSTAMI on CLOSE-UP (2009) Interviewed by Tarik Benbrahim for the Criterion Collection Close-Up was a film that I could say I didn't really make. It wasn't my doing. Because if the definition of director is someone who controls everything, fortunately or unfortunately, I didn't have any control over this film from the start. The elements were not within my control, behind the scenes or in front of the camera. The story is that I wanted to make a movie for children, about children, about pocket money - money they usually get from their parents. Everything was ready for us to go to a school and start filming on a Saturday morning. I remember that I'd read an article in the newspaper that Thursday, an interview with someone who had impersonated a filmmaker. -

Presskit.Pdf

ten a film by Abbas Kiarostami Celebrated Iranian writer-director Abbas Kiarostami (Taste of Cherry, Through the Olive Trees) once again casts his masterful cinematic gaze upon the modern sociopolitical landscape of his homeland—this time as seen through the eyes of one woman as she drives through the streets of Tehran over a period of several days. Her journey is comprised of ten conversations with various female passengers—including her sister, a hitchhiking prostitute and a jilted bride—as well as her imperious young son. As Kiarostami’s “dashboard cam” eavesdrops on these lively, yet heart-wrenching road trips, a complex portrait of contemporary Iran comes sharply into focus. Kiarostami on TEN Sometimes, I tell myself that TEN is a film that I could never make again. You cannot decide to make such a film... It’s a little like CLOSE-UP. It's possible to continue along the same path but it requires a great deal of patience. Indeed, this is not something that can be reapeated easily. It must occur of its own accord, like an incident or a happening... At the same time, it requires a great deal of preparation. Originally, this was the story of a psychoanyalyst her patients and her car, but that was two years ago... I was invited to Beirut in Lebanon last week, for a film workshop with students. One of them told me, “You’re the only one who can make such a film because of your reputation. If one of us had made it, no one would have accepted it.” I replied that, as his teacher, I owed him the truth: making something simple requires a great deal of experience. -

Abbas Kiarostami a Retrospective

PRESENTS ABBAS KIAROSTAMI A RETROSPECTIVE “Film begins with D. W. Griffith and ends with Abbas Kiarostami.” —Jean-Luc Godard Janus Films is proud to present a touring retrospective spanning Abbas Kiarostami’s nearly five-decade career. The series will include new restorations of The Koker Trilogy, Taste of Cherry, The Wind Will Carry Us, and rarely screened shorts and documentaries. RESTORATION INFORMATION The 2K digital restoration of The Koker Trilogy was undertaken The remaining 2K and 4K restorations were undertaken by MK2 in by the Criterion Collection from 4K scans of the 35 mm original collaboration with L’Immagine Ritrovata from 2K or 4K scans of the camera negatives. best available elements. Booking Inquiries: Janus Films Press Contact: Courtney Ott [email protected] • 212-756-8761 [email protected] • 646-230-6847 Text by Godfrey Cheshire BIOGRAPHY The most acclaimed and influential international renown. Where Is the period, The Wind Will Carry Us (1999), of Iran’s major filmmakers, Abbas Friend’s House? (1987), about a rural which concerns a camera crew on an Kiarostami was born in Tehran on boy’s effort to return a pal’s notebook, enigmatic assignment in Kurdistan, June 22, 1940. Raised in a middle- won the Bronze Leopard at the Locarno won the Silver Lion at the Venice class household, he was interested in Film Festival. Close-up (1990), about the Film Festival. art and literature from an early age. trial of a man accused of impersonating During and after university, where a famous filmmaker, was the director’s In the new century, Kiarostami he majored in painting and graphic first film to focus on cinema itself, and broadened his creative focus, devoting design, he illustrated children’s to blur the lines between documentary more time to forms including books, designed credit sequences for and fiction; it has been voted the best photography, installation art, poetry, films, and made numerous television Iranian film ever made by Iranian and and teaching. -

IT's TIME to DIE by Krzysztof Zanussi

IT’S TIME TO DIE by Krzysztof Zanussi translated by Anna Piwowarska // Stephen Davies 1 INTRODUCTION The grim title of this book originates from an anecdote and I ask you to treat it as a joke. I don’t intend to die soon or persuade anyone to relocate to the afterworld. But a certain era is dying before our very eyes and if someone is very attached to it, they should take my words to heart. This is what this book is to be about. But first, about that anecdote. It comes from a great actor, Jerzy Leszczynski. For me, a fifty-something-year-old, this surname is still very much alive. I saw Jerzy in a few roles in the ‘Polish Theatre’ just after the war; I also saw him in many pre-war films (after the war I think he only acted in ‘Street Boundary’). He was an actor from those pre-war years: handsome, endowed with a wonderful appearance and a beautiful voice. He played kings, military commanders, warlords and this is how the audiences loved him. After the war, he acted in radio plays – he had beautiful pre-war diction and of course he pronounced the letter ‘ł’ and he didn't swallow his vowels. Apart from this, he was known for his excellent manners, which befitted an actor who played kings and military commanders. When the time of the People’s Republic came, the nature of the main character that was played out on stage changed. The recruitment of actors also changed: plebeian types were sought after - 'bricklaying teams' and 'girls on tractors who conquered the spring'.