Coalition of the Willing Or Coalition of the Coerced?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phyllis Bennis

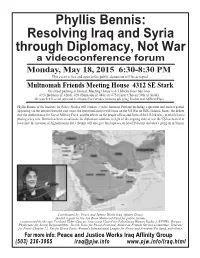

Phyllis Bennis: Resolving Iraq and Syria through Diplomacy, Not War a videoconference forum Monday, May 18, 2015 6:30-8:30 PM This event is free and open to the public; donations will be accepted. Multnomah Friends Meeting House 4312 SE Stark On-street parking is limited; Meeting House is 4-5 blocks from bus lines #15 (Belmont @ 42nd), #20 (Burnside @ 44th) or #75 (Cesar Chavez/39th @ Stark). Or watch it live on ustream.tv/channel/occucakes (remove ads using Firefox and AdBlockPlus) Phyllis Bennis of the Institute for Policy Studies will conduct a video forum in Portland including a question and answer period Appearing via the internet from the east coast, the renowned analyst will focus on the US War on ISIS (/Islamic State), the debate over the Authorization for Use of Military Force, and the effects on the people of Iraq and Syria of the US-led war-- in which Iran is playing a key role. Bennis has been an advocate for diplomatic solutions in light of the ongoing state of war the US has been in at least since the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. Bennis will also give brief updates on Israel/Palestine and what's going on in Yemen. Coordinated by: Peace and Justice Works Iraq Affinity Group, funded in part by the Jan Bone Memorial Fund for public forums. cosponsored by Occupy Portland Elder Caucus, Americans United for Palestinian Human Rights (AUPHR), Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility, Jewish Voice for Peace-Portland, American Friends Service Committee, Veterans for Peace Chapter 72, Pacific Green Party, Women's International League for Peace and Freedom-Portland, and others. -

U. S. Foreign Policy1 by Charles Hess

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE U. S. Foreign Policy1 by Charles Hess They hate our freedoms--our freedom of religion, our freedom of speech, our freedom to vote and assemble and disagree with each other (George W. Bush, Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People, September 20, 2001). These values of freedom are right and true for every person, in every society—and the duty of protecting these values against their enemies is the common calling of freedom-loving people across the globe and across the ages (National Security Strategy, September 2002 http://www. whitehouse. gov/nsc/nss. html). The historical connection between U.S. foreign policy and human rights has been strong on occasion. The War on Terror has not diminished but rather intensified that relationship if public statements from President Bush and his administration are to be believed. Some argue that just as in the Cold War, the American way of life as a free and liberal people is at stake. They argue that the enemy now is not communism but the disgruntled few who would seek to impose fundamentalist values on societies the world over and destroy those who do not conform. Proposed approaches to neutralizing the problem of terrorism vary. While most would agree that protecting human rights in the face of terror is of elevated importance, concern for human rights holds a peculiar place in this debate. It is ostensibly what the U.S. is trying to protect, yet it is arguably one of the first ideals compromised in the fight. -

International Law and the 2003 Invasion of Iraq Revisited

International Law and the 2003 Invasion of Iraq Revisited Donald K. Anton Associate Professor of Law The Australian National University College of Law Paper delivered April 30, 2013 Australian National University Asia-Pacific College of Diplomacy The Invasion of Iraq: Canadian and Australian Perspectives Seminar1 INTRODUCTION Good morning. Thank you to the organizers for inviting me to participate today in this retrospective on the 2003 invasion of Iraq. My role this morning, as I understand it, is to parse the international legal arguments surrounding the invasion and to reconsider them in the fullness of time that has elapsed. It is a role I agreed to take on with hesitation because it is difficult to add much that is new. I suppose I can take comfort in saying what I’ve already said, and saying it again today, because of how I view my obligations as an international lawyer. I believe we lawyers have a duty to stand up and insist that our leaders adhere to the rule of law in international relations and to help ensure that they are held accountable for the failure to do so. As I am sure you are all aware, much remains to be done in terms of accountability, especially in the United States, and it is disappointing that the Obama Administration has so far refused to prosecute what seem to be clear violations of the Torture Convention, including all the way up the chain of command if necessary. Today, however, my talk is confined to the legal arguments about the use of force in Iraq and an analysis of their persuasiveness. -

And Pale Odia Palestinian Woman in Jabaliya Camp, Gaza Strip

and Pale odia Palestinian woman in Jabaliya Camp, Gaza Strip. Her home was demolished by Israeli military, (p.16) (Photo: Neal Cassidy) nunTHE JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE FOR PROGRESSIVE WOMEN VOL. XV SUMMER 1990 PUBLISHER/EDITOR IN CHIEF Merle Hoffman MANAGING EDITOR Beverly Lowy ASSOCIATE EDITOR Eleanor J. Bader ASSISTANT EDITOR Karen Aisenberg EDITOR AT LARGE Phyllis Chester CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Charlotte Bunch Vinie Burrows Naomi Feigelson Chase Irene Davall FEATURES Above: Goats on a porch at Toi Derricotte Mandala. All animals are treated with Roberta Kalechofsky BREAKING BARRIERS: affection and respect, even the skunks. Flo Kennedy WOMEN AND MINORITIES IN (p.10) (Photo: Helen M. Stummer) Fred Pelka THE SCIENCES Cover: A single mother and her Helen M. Stummer ON THE ISSUES interviews children find permanency in a H.O.M.E.- ART DIRECTORS Paul E. Gray, President of MIT, and built home. (Photo: Helen M. Stummer) Michael Dowdy Dean of Student Affairs, Shirley M. Julia Gran McBay, on sexism and racism in A SONG SO BRAVE — ADVERTISING AND SALES academia 7 PHOTO ESSAY DIRECTOR Text By Phyllis Chesler Carolyn Handel H.O.M.E. Photos By Joan Roth ONE WOMAN'S APPROACH Phyllis Chesler and an international ON THE ISSUES: A feminist, humanist TO SOCIETY'S PROBLEMS group of feminists present a Torah to publication dedicated to promoting By Helen M. Stummer political action through awareness and the women of Jerusalem 19 education; working toward a global Visual sociologist Helen M. Stummer political consciousness; fostering a spirit profiles a unique program to combat TO PEE OR NOT TO PEE of collective responsibility for positive homelessness, poverty and By Irene Davall social change; eradicating racism, disenfranchisement 10 A humorous recollection of the "pee- sexism, ageism, speciesism; and support- in" that forced Harvard to examine its ing the struggle of historically disenfran- FROM STONES TO sexism 20 chised groups to protect and defend STATEHOOD themselves. -

Medical Discrimination in the Time of COVID-19: Unequal Access to Medical Care in West Bank and Gaza Hana Cooper Seattle University ‘21, B.A

Medical Discrimination in the Time of COVID-19: Unequal Access to Medical Care in West Bank and Gaza Hana Cooper Seattle University ‘21, B.A. History w/ Departmental Honors ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE A SYSTEM OF DISCRIMINATION COVID-19 IMPACT Given that PalestiniansSTRACT are suffering from As is evident from headlines over the last year, Palestinians are faring much worse While many see the founding of Israel in 1948 as the beginning of discrimination against COVID-19 has amplified all of the existing issues of apartheid, which had put Palestinians the COVID-19 pandemic not only to a under the COVID-19 pandemic than Israelis. Many news sources focus mainly on the Palestinians, it actually extends back to early Zionist colonization in the 1920s. Today, in a place of being less able to fight a pandemic (or any major, global crisis) effectively. greater extent than Israelis, but explicitly present, discussing vaccine apartheid and the current conditions of West Bank, Gaza, discrimination against Palestinians continues at varying levels throughout West Bank, because of discriminatory systems put into and Palestinian communities inside Israel. However, few mainstream news sources Gaza, and Israel itself. Here I will provide some examples: Gaza Because of the electricity crisis and daily power outages in Gaza, medical place by Israel before the pandemic began, have examined how these conditions arose in the first place. My project shows how equipment, including respirators, cannot run effectively throughout the day, and the it is clear that Israel is responsible for taking the COVID-19 crisis in Palestine was exacerbated by existing structures of Pre-1948 When the infrastructure of what would eventually become Israel was first built, constant disruptions in power cause the machines to wear out much faster than they action to ameliorate the crisis. -

The Bush Revolution: the Remaking of America's Foreign Policy

The Bush Revolution: The Remaking of America’s Foreign Policy Ivo H. Daalder and James M. Lindsay The Brookings Institution April 2003 George W. Bush campaigned for the presidency on the promise of a “humble” foreign policy that would avoid his predecessor’s mistake in “overcommitting our military around the world.”1 During his first seven months as president he focused his attention primarily on domestic affairs. That all changed over the succeeding twenty months. The United States waged wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. U.S. troops went to Georgia, the Philippines, and Yemen to help those governments defeat terrorist groups operating on their soil. Rather than cheering American humility, people and governments around the world denounced American arrogance. Critics complained that the motto of the United States had become oderint dum metuant—Let them hate as long as they fear. September 11 explains why foreign policy became the consuming passion of Bush’s presidency. Once commercial jetliners plowed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, it is unimaginable that foreign policy wouldn’t have become the overriding priority of any American president. Still, the terrorist attacks by themselves don’t explain why Bush chose to respond as he did. Few Americans and even fewer foreigners thought in the fall of 2001 that attacks organized by Islamic extremists seeking to restore the caliphate would culminate in a war to overthrow the secular tyrant Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Yet the path from the smoking ruins in New York City and Northern Virginia to the battle of Baghdad was not the case of a White House cynically manipulating a historic catastrophe to carry out a pre-planned agenda. -

Press Release United Nations Department of Public Information • News and Media Services Division • New York PAL/1887 PI/1354 13 June 2001

Press Release United Nations Department of Public Information • News and Media Services Division • New York PAL/1887 PI/1354 13 June 2001 DPI TO HOST INTKRNATIONAI, MEDIA ENCOUNTER ON QUESTION OF PALESTINE IN PARIS, 18 - 19 JUNE Search for Peace in Middle East, Role of United Nations To Be Discussed Prominent journalists and Middle East experts, including senior officials and lawmakers from Israel and the Palestinian Authority, will meet at the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) headquarters in Paris, on 18 and 19 June, at an international media encounter on the question of Palestine organized by the Department of Public Information (DPI). The overall theme of the encounter is "The search for peace in the Middle East". It is designed as a forum where media representatives and international experts will have an opportunity to discuss the status of the peace process, ways and means to break the deadlock, and the cycle of violence and reporting about the developments in the Middle East. They will also discuss the role of the United Nations in the question of Palestine and in the overall search for peace in the Middle East. The Secretary-General of the United Nations is expected to issue a message welcoming the participants, which will be delivered by Shashi Tharoor, Interim Head, DPI. The Secretary-General of the French Foreign Ministry, Loic Hennekinne, and the Director-General of UNESCO, Koichiro Matsuura, will also welcome the participants. Terje Roed-Larsen, United Nations Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process and Personal Representative of the Secretary-General to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Palestinian Authority, will present the keynote address of the encounter, focusing on the peace process in the Middle East. -

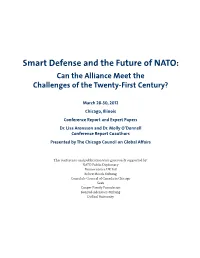

Smart Defense and the Future of NATO: Can the Alliance Meet the Challenges of the Twenty-First Century?

Smart Defense and the Future of NATO: Can the Alliance Meet the Challenges of the Twenty-First Century? March 28-30, 2012 Chicago, Illinois Conference Report and Expert Papers Dr. Lisa Aronsson and Dr. Molly O’Donnell Conference Report Coauthors Presented by The Chicago Council on Global Affairs This conference and publication were generously supported by: NATO Public Diplomacy Finmeccanica UK Ltd Robert Bosch Stiftung Consulate General of Canada in Chicago Saab Cooper Family Foundation Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung DePaul University NATO’s Inward Outlook: Global Burden Shifting Josef Braml Editor-in-Chief, DGAP Yearbook, German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) Abstract: While European NATO partners have their difficulties coping with economic problems, the dire eco- nomic and budgetary situation in the United States matters more for the alliance. We have become familiar with the challenges European members face in fulfilling their obligations. But we should understand that NATO’s lead nation, shouldering three-quarters of the alliance’s operating budget, is in deep economic, bud- getary, and political trouble. Hence the United States will seek ways to share the burden with partners inside and outside NATO. With the instrument of a “global NATO,” the United States continues to assert its values and interests worldwide. In addition to the transatlantic allies, democracies in Asia will be invited to contribute their financial and military share to establish a liberal world order. Domestic pressure: The power of the from Congress to check spending, would make it necessary for the commander in chief to find a way empty purse to cost-effectively balance the competing demands for resources in his new security strategy. -

Iceland and “The Coalition of the Willing”

UNIVERSITY OF AKUREYRI DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES FACULTY OF LAW, 2011 Iceland and “The Coalition Of The Willing” Was Iceland’s Declaration of Support Legal According to Icelandic Law? By, Hjalti Ómar Ágústsson 13 May 2011 Department of Humanities and Social Sciences BA Thesis UNIVERSITY OF AKUREYRI DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES FACULTY OF LAW, 2011 Iceland and “The Coalition Of The Willing” Was Iceland’s Declaration of Support Legal According to Icelandic Law? By, Hjalti Ómar Ágústsson 13/5/2011 Instructor: Rachael Lorna Johnstone Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Final Thesis Towards a BA Degree in Law (180 ECTS Credits) Declarations: I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis and that it is the product of my own research. ____________________________ Hjalti Ómar Ágústsson It is hereby certified that in my judgment, this thesis fulfils the requirements for a B.A. degree at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences. ________________________________ Dr. Rachael Lorna Johnstone i Abstract In a press briefing in the United States Department of State on 18 March 2003, Iceland‟s name appeared on a list of nations who were willing to support in one way or another an invasion into Iraq without explicit Security Council support or authorization. These states are commonly known as “The Coalition of the Willing”. Consequently Iraq was invaded on 20 March 2003 by four member states of the Coalition. The invasion was justified based on a combination of Security Council resolution 1441 and prior resolutions which together were interpreted as giving implied authorization, and on anticipatory self-defense based on Article 51 of the UN Charter. -

Japan's ''Coalition of the Willing'

Japan’s ‘‘Coalition of the Willing’’ on Security Policies by Robert Pekkanen and Ellis S. Krauss Robert Pekkanen ([email protected]) is assistant professor of international studies at the University of Washington. Ellis S. Krauss ([email protected]) is professor of interna- tional relations and Pacific studies at the University of California, San Diego. This paper is based on a paper presented at fpri’s January 27, 2005, conference, ‘‘Party Politics and Foreign Policy in East Asia,’’ held in Philadelphia. The authors thank Michael Strausz for his research assistance. n 1991, Japan was vilified by many for its ‘‘failure’’ to contribute boots on the ground to the U.S.-led Gulf War. Prime Minister Toshiki Kaifu (1989– I 91) found it difficult to gain support for any cooperation with the U.S.-led coalition in that conflict. Today, Japan’s Self-Defense Forces are stationed in a compound in Samuur, Iraq, part of President Bush’s ‘‘coalition of the willing,’’ and four of its destroyers are positioned in the Indian Ocean to aid the counterterrorism effort in Afghanistan. While many of the United States’ nato allies have been reluctant to aid current American security efforts, especially in Iraq, Japan has been among the staunchest supporters of American military ventures in the Middle East and of its stance toward North Korean nuclear development. As a result, Washington has moved from ‘‘bashing Japan’’ in the 1980s over trade policy and ‘‘passing Japan’’—ignoring it in favor of the rest of Asia—to lauding it for surpassing most of American’s other defense partners. -

An Analysis of Kiribati, Nauru, Palau, Tonga, Tuvalu and Mauritius Thomas M

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2004 Small-State Foreign Policy: An Analysis of Kiribati, Nauru, Palau, Tonga, Tuvalu and Mauritius Thomas M. Ethridge Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Political Science at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Ethridge, Thomas M., "Small-State Foreign Policy: An Analysis of Kiribati, Nauru, Palau, Tonga, Tuvalu and Mauritius" (2004). Masters Theses. 1325. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1325 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS/FIELD EXPERIENCE PAPER REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is receiving a number of request from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow these to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that · dings. ~Ju } oy Oat~ 1 I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University NOT allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author's Signature Date lhesis4.form SMALL-STATE FOREIGN POLICY: AN ANALYSIS OF KIRIBATI, NAURU, PALAU, TONGA, TUVALU AND MAURITIUS (TITLE) BY Thomas M. -

Reexamining the US-Turkish Alliance

Joshua W. Walker Reexamining the U.S.-Turkish Alliance The July 22, 2007, Turkish national elections instigated a series of political debates in Turkey about the role of the 60-year-old U.S. alliance and the future orientation of Turkish foreign policy. Does Turkey still need its U.S. alliance in a post–Cold War environment? Particularly after U.S. pres- sure on Turkey in 2003 to open a northern front in the war in Iraq, which the Turkish parliament rejected, and given how unpopular the United States has become in the Middle East and in Europe, is the alliance still valuable to An- kara today? Coupled with the deteriorating situation in Iraq and the constant threat of the Turkish use of force in northern Iraq, these debates have forced U.S.-Turkish relations onto the international scene. The severity of the es- trangement in relations has been consistently downplayed on both sides of the Atlantic, even while external factors such as Turkey’s floundering EU mem- bership process and regional differences over how to deal with Iraq have only exacerbated the problems in the alliance. The fallout from the Iraq war has now gone beyond a simple misunderstanding between the United States and Turkey and casts a dark shadow over future relations and the wider regional security structure of the Middle East. The emergence of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) as a political force in Turkish politics has coincided with this unprecedented estrangement in U.S.-Turkish relations. Although the 2002 elections allowed the AKP to form a single-party government, their legitimacy was disputed.