Prestel Munich Berlin London New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murdoch's Global Plan For

CNYB 05-07-07 A 1 5/4/2007 7:00 PM Page 1 TOP STORIES Portrait of NYC’s boom time Wall Street upstart —Greg David cashes in on boom on the red hot economy in options trading Page 13 PAGE 2 ® New Yorkers are stepping to the beat of Dancing With the Stars VOL. XXIII, NO. 19 WWW.NEWYORKBUSINESS.COM MAY 7-13, 2007 PRICE: $3.00 PAGE 3 Times Sq. details its growth, worries Murdoch’s about the future PAGE 3 global plan Under pressure, law firms offer corporate clients for WSJ contingency fees PAGE 9 421-a property tax Times, CNBC and fight heads to others could lose Albany; unpacking out to combined mayor’s 2030 plan Fox, Dow Jones THE INSIDER, PAGE 14 BY MATTHEW FLAMM BUSINESS LIVES last week, Rupert Murdoch, in a ap images familiar role as insurrectionist, up- RUPERT MURDOCH might bring in a JOINING THE PARTY set the already turbulent media compatible editor for The Wall Street Journal. landscape with his $5 billion offer for Dow Jones & Co. But associ- NEIL RUBLER of Vantage Properties ates and observers of the News media platform—including the has acquired several Corp. chairman say that last week planned Fox Business cable chan- thousand affordable was nothing compared with what’s nel—and take market share away housing units in the in store if he acquires the property. from rivals like CNBC, Reuters past 16 months. Campaign staffers They foresee a reinvigorated and the Financial Times. trade normal lives for a Dow Jones brand that will combine Furthermore, The Wall Street with News Corp.’s global assets to Journal would vie with The New chance at the White NEW POWER BROKERS House PAGE 39 create the foremost financial news York Times to shape the national and information provider. -

Museum of American Finance

By Katie Petito Alexander Hamilton would be proud. Founded in 1794 by Hamilton, the first treasury secretary of the U.S., the Bank of New York, opened its first building at the Walton House in Lower Manhattan on June 9, 1784, only a few months after the departure of British troops from American soil. In 1797, the Bank laid the cornerstone for its first building at 48 Wall Street – a two-story Georgian building that served as the bank’s headquarters through the beginning of the 19th century. Although the original building no longer stands, its cornerstone can be seen at the current 48 Wall Street building. The 48 Wall Street building, located one block east of the New York Stock Exchange, will be the new home to the Museum of American Finance. The 30,000-square foot space occupies three of the landmark building’s 36 floors, increasing the Museum’s exhibit space by ten-fold. The Museum, now housed in the Standard Oil Building at 26 Broadway, will open in its new location in early spring 2007, but will honor its financial roots sooner with a symposium on January 11, 2007, to celebrate Alexander Hamilton’s 250th birthday. The symposium will also offer guests a sneak peek at the Museum’s Alexander Hamilton exhibit. A grand opening for the general public will be announced at a later date. “Perhaps there is no more fitting home for the Museum of American Finance than the former headquarters of New York’s first bank, which was founded by Alexander Hamilton, creator of our nation’s financial system,” said John Herzog, founder and chair of the Museum. -

General Info.Indd

General Information • Landmarks Beyond the obvious crowd-pleasers, New York City landmarks Guggenheim (Map 17) is one of New York’s most unique are super-subjective. One person’s favorite cobblestoned and distinctive buildings (apparently there’s some art alley is some developer’s idea of prime real estate. Bits of old inside, too). The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (Map New York disappear to differing amounts of fanfare and 18) has a very medieval vibe and is the world’s largest make room for whatever it is we’ll be romanticizing in the unfinished cathedral—a much cooler destination than the future. Ain’t that the circle of life? The landmarks discussed eternally crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Map 12). are highly idiosyncratic choices, and this list is by no means complete or even logical, but we’ve included an array of places, from world famous to little known, all worth visiting. Great Public Buildings Once upon a time, the city felt that public buildings should inspire civic pride through great architecture. Coolest Skyscrapers Head downtown to view City Hall (Map 3) (1812), Most visitors to New York go to the top of the Empire State Tweed Courthouse (Map 3) (1881), Jefferson Market Building (Map 9), but it’s far more familiar to New Yorkers Courthouse (Map 5) (1877—now a library), the Municipal from afar—as a directional guide, or as a tip-off to obscure Building (Map 3) (1914), and a host of other court- holidays (orange & white means it’s time to celebrate houses built in the early 20th century. -

New York CITY

New York CITY the 123rd Annual Meeting American Historical Association NONPROFIT ORG. 400 A Street, S.E. U.S. Postage Washington, D.C. 20003-3889 PAID WALDORF, MD PERMIT No. 56 ASHGATENew History Titles from Ashgate Publishing… The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir The Long Morning of Medieval Europe for the Crusading Period New Directions in Early Medieval Studies Edited by Jennifer R. Davis, California Institute from al-Kamil fi’l-Ta’rikh. Part 3 of Technology and Michael McCormick, The Years 589–629/1193–1231: The Ayyubids Harvard University after Saladin and the Mongol Menace Includes 25 b&w illustrations Translated by D.S. Richards, University of Oxford, UK June 2008. 366 pages. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6254-9 Crusade Texts in Translation: 17 June 2008. 344 pages. Hbk. 978-0-7546-4079-0 The Art, Science, and Technology of Medieval Travel The Portfolio of Villard de Honnecourt Edited by Robert Bork, University of Iowa (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale and Andrea Kann AVISTA Studies in the History de France, MS Fr 19093) of Medieval Technology, Science and Art: 6 A New Critical Edition and Color Facsimile Includes 23 b&w illustrations with a glossary by Stacey L. Hahn October 2008. 240 pages. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6307-2 Carl F. Barnes, Jr., Oakland University Includes 72 color and 48 b&w illustrations November 2008. 350 pages. Hbk. 978-0-7546-5102-4 The Medieval Account Books of the Mercers of London Patents, Pictures and Patronage An Edition and Translation John Day and the Tudor Book Trade Lisa Jefferson Elizabeth Evenden, Newnham College, November 2008. -

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 22, 2016, Designation List 490 LP-2579

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 22, 2016, Designation List 490 LP-2579 YALE CLUB OF NEW YORK CITY 50 Vanderbilt Avenue (aka 49-55 East 44th Street), Manhattan Built 1913-15; architect, James Gamble Rogers Landmark site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1279, Lot 28 On September 13, 2016, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of the Yale Club of New York City and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site. The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Six people spoke in support of designation, including representatives of the Yale Club of New York City, Manhattan Borough President Gale A. Brewer, Historic Districts Council, New York Landmarks Conservancy, and the Municipal Art Society of New York. The Real Estate Board of New York submitted written testimony in opposition to designation. State Senator Brad Hoylman submitted written testimony in support of designation. Summary The Yale Club of New York City is a Renaissance Revival-style skyscraper at the northwest corner of Vanderbilt Avenue and East 44th Street. For more than a century it has played an important role in East Midtown, serving the Yale community and providing a handsome and complementary backdrop to Grand Central Terminal. Constructed on property that was once owned by the New York Central Railroad, it stands directly above two levels of train tracks and platforms. This was the ideal location to build the Yale Club, opposite the new terminal, which serves New Haven, where Yale University is located, and at the east end of “clubhouse row.” The architect was James Gamble Rogers, who graduated from Yale College in 1889 and attended the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris during the 1890s. -

CENTURY APARTMENTS, 25 Central Park West, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission July 9, 1985, Designation List 181 LP-1517 CENTURY APARTMENTS, 25 Central Park West, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1931; architect Irwin S. Chanin. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1115, Lot 29. On September 11, 1984, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Century Apartments and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 11). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Thirteen witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Century Apartments, extending along the entire blockfront of Central Park West between West 62nd Street to West 63rd Street, anchors the southern end of one of New York City's finest residential boulevards. With twin towers rising 300 feet from the street, this building is one of a small group of related structures that help give Central Park West its distinctive silhouette. Designed in 1930 by Irwin S. Chanin of the Chanin Construction Company, the Century Apartments is among the most sophisticated residential Art Deco buildings in New York and is a major work by one of America's pioneering Art Deco designers. Built in 1931, the Century was among the last buildings erected as part of the early 20th-century redevelopment of Central Park West. Central Park West, a continuation of Eighth Avenue, runs along the western edge of Central Park. Development along this prime avenue occurred very slowly , lagging sub stantially behind the general development of the Upper West Side. -

June 2014 Scope of Feasibility Study Evaluates Technical, Legal and Financial Feasibility of the Multi-Purpose Levee (MPL) Concept

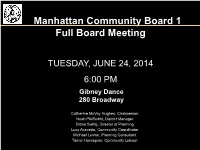

Manhattan Community Board 1 Full Board Meeting TUESDAY, JUNE 24, 2014 6:00 PM Gibney Dance 280 Broadway Catherine McVay Hughes, Chairperson Noah Pfefferblit, District Manager Diana Switaj, Director of Planning Lucy Acevedo, Community Coordinator Michael Levine, Planning Consultant Tamar Hovsepian, Community Liaison Manhattan Community Board 1 Public Session Comments by members of the public (6 PM to 7 PM) (Please limit to 1-2 minutes per speaker, to allow everyone to voice their opinions) Welcome: Gina Gibney, Chief Executive Officer & Artistic Director of Gibney Dance Guest Speaker: Frank McCarton, Deputy Commissioner of Operations, NYC Office of Emergency Management Making SPACE FOR CULTURE MANHATTAN COMMUNITY DISTRICT 1 PUBLIC SCHOOLS (DRAFT) Elementary School Middle School High School Charter School Symbol sizes determined by student enrollment number Sources: NYC DOE & NYC DOE School Portal Websites CHA CODE SCHOOL NAME RTE SCHOOL GRADES ENROLLM ADDRESS R TYPE ENT M089 P.S. 89 Elementary PK,0K,01,02,03,04,05,SE 464 201 WARREN STREET Middle M289 I.S. 289 School 06,07,08,SE 290 201 WARREN STREET M150 P.S. 150 Elementary PK,0K,01,02,03,04,05 181 334 GREENWICH STREET P.S. 234 INDEPENDENCE M234 SCHOOL Elementary 0K,01,02,03,04,05,SE 779 292 GREENWICH STREET M418 MILLENNIUM HIGH SCHOOL High school 09,10,11,12,SE 617 75 BROAD STREET LEADERSHIP AND PUBLIC M425 SERVICE HIGH SCHOOL High school 09,10,11,12,SE 673 90 TRINITY PLACE HIGH SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS M489 AND FINANCE High school 09,10,11,12,SE 737 100 TRINITY PLACE M475 STUYVESANT HIGH SCHOOL High school 09,10,11,12 3280 345 CHAMBERS STREET JOHN V. -

Carnegie Hall a Rn Eg Ie an D H Is W Ife Lo 12 Then and Now Uise, 19

A n d r e w C Carnegie Hall a rn eg ie an d h is w ife Lo 12 Then and Now uise, 19 Introduction The story of Carnegie Hall begins in the middle of the Atlantic. itself with the history of our country.” Indeed, some of the most In the spring of 1887, on board a ship traveling from New York prominent political figures, authors, and intellectuals have to London, newlyweds Andrew Carnegie (the ridiculously rich appeared at Carnegie Hall, from Woodrow Wilson and Theodore industrialist) and Louise Whitfield (daughter of a well-to-do New Roosevelt to Mark Twain and Booker T. Washington. In addition to York merchant) were on their way to the groom’s native Scotland standing as the pinnacle of musical achievement, Carnegie Hall has for their honeymoon. Also on board was the 25-year-old Walter been an integral player in the development of American history. Damrosch, who had just finished his second season as conductor and musical director of the Symphony Society of New York and ••• the Oratorio Society of New York, and was traveling to Europe for a summer of study with Hans von Bülow. Over the course of After he returned to the US from his honeymoon, Carnegie set in the voyage, the couple developed a friendship with Damrosch, motion his plan, which he started formulating during his time with inviting him to visit them in Scotland. It was there, at an estate Damrosch in Scotland, for a new concert hall. He established The called Kilgraston, that Damrosch discussed his vision for a new Music Hall Company of New York, Ltd., acquired parcels of land concert hall in New York City. -

Spitzer's Aides Find It Difficult to Start Anew

CNYB 07-07-08 A 1 7/3/2008 7:17 PM Page 1 SPECIAL SECTION NBA BETS 2008 ON OLYMPICS; ALL-STAR GAME HITS HOME RUN IN NEW YORK ® PAGE 3 AN EASY-TO-USE GUIDE TO THE VOL. XXIV, NO. 27 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM JULY 7-13, 2008 PRICE: $3.00 STATISTICS Egos keep THAT MATTER THIS Spitzer’s aides YEAR IN NEW YORK newspaper PAGES 9-43 find it difficult presses INCLUDING: ECONOMY rolling FINANCIAL to start anew HEALTH CARE Taking time off to decompress Local moguls spend REAL ESTATE millions even as TOURISM life. Paul Francis, whose last day business turns south & MORE BY ERIK ENGQUIST as director of operations will be July 11, plans to take his time three months after Eliot before embarking on his next BY MATTHEW FLAMM Spitzer’s stunning demise left endeavor, which he expects will them rudderless,many members be in the private sector. Senior ap images across the country,the newspa- of the ex-governor’s inner circle adviser Lloyd Constantine,who per industry is going through ar- have yet to restart their careers. followed Mr. Spitzer to Albany TEAM SPITZER: guably the darkest period in its A few from the brain trust that and bought a house there, has THEN AND NOW history, with publishers slashing once seemed destined to reshape yet to return to his Manhattan newsroom staff and giants like Tri- the state have moved on to oth- law firm, Constantine Cannon. RICH BAUM bune Co.standing on shaky ground. AT DEADLINE er jobs, but others are taking Working for the hard-driv- WAS The governor’s Things are different in New time off to decompress from the ing Mr.Spitzer,“you really don’t secretary York. -

Chevron Plaza up to 12,272 Sf for Lease

Chevron Plaza Up to 12,272 sf for lease VIEW THE VIRTUAL TOUR John Engbloom Damon Harmon, CPA, CGA Josh Manerikar 403.617.3029 403.875.3133 403.988.9546 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Chevron Plaza Up to 12,272 sf available Space Profile immediately Landlord: Chevron Canada Resources Ltd. Premises: 10th Floor: 12,272 sf Availability: Immediately Term Expiry: 2 - 5 years Rental Rate: $21.50 per sf gross rates Features & Amenities T.I.A.: As is Parking: 1 stall per 3,000 sf Recently renovated well improved premises with demountable wall system Fully furnished with new furniture including electronic height adjustable desk for tenant use and all meeting/boardroom furniture in place Building Information Efficient office intensive layout with approximately 45 offices Address: 500 Fifth Avenue SW Recently renovated elevators and lobbies Year of Completion: 1981 New conference centre located on the 4th floor available for tenant use Number of Floors: 23 Plus 15 connections to 520 – 5 Avenue SW & Rentable Area: 267,000 sf 444 – 5 Avenue SW Average Floor plate: 12,272 sf Security: Card key access HVAC: 7 days per week 24 hours per day Chevron Plaza 10th Floor 12,272 sf 31 perimeter offices Chevron Business and Real Estate Services 14 interior offices Calgary, Alberta, Canada 2 meeting rooms CHEVRON CANADA RESOURCES CHEVRON PLAZA - TENTH FLOOR Boardroom Kitchen 1054 1060 1062 1048 1050 1052 1056 1058 PEN 01 Copy station COR 03 1046 1057 1009 1002 1059 1045 1055 1001 1061 1044 1011 1004 1003 1013 1042 1006 ELEC 01 1039D TEL 01 ELEV 1 MENS 1015 1005 1008 1040 1039C ELEV 5 ELEV 2 UNIVER PEN 03 STAIR A-B 1038 1017 1007 1010 ELEV 3 ELEV 6 1039B WOMENS 1019 1012 TEL 02 1036 ELEV 4 ELEV 7 1039A JAN 01 COR 01 LOBBY 1034 1016 1014 1031 1029 1027 1025 1023 1032 1018 COR 02 PEN 02 1030 1028 1026 1024 1022 1020 BL1000405-10-ARC-FLP-CVX-002-1 - October 4, 2019 FLOOR PLAN NOT TO SCALE. -

Manhattan Year BA-NY H&R Original Purchaser Sold Address(Es)

Manhattan Year BA-NY H&R Original Purchaser Sold Address(es) Location Remains UN Plaza Hotel (Park Hyatt) 1981 1 UN Plaza Manhattan N Reader's Digest 1981 28 West 23rd Street Manhattan Y NYC Dept of General Services 1981 NYC West Manhattan * Summit Hotel 1981 51 & LEX Manhattan N Schieffelin and Company 1981 2 Park Avenue Manhattan Y Ernst and Company 1981 1 Battery Park Plaza Manhattan Y Reeves Brothers, Inc. 1981 104 W 40th Street Manhattan Y Alpine Hotel 1981 NYC West Manhattan * Care 1982 660 1st Ave. Manhattan Y Brooks Brothers 1982 1120 Ave of Amer. Manhattan Y Care 1982 660 1st Ave. Manhattan Y Sanwa Bank 1982 220 Park Avenue Manhattan Y City Miday Club 1982 140 Broadway Manhattan Y Royal Business Machines 1982 Manhattan Manhattan * Billboard Publications 1982 1515 Broadway Manhattan Y U.N. Development Program 1982 1 United Nations Plaza Manhattan N Population Council 1982 1 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza Manhattan Y Park Lane Hotel 1983 36 Central Park South Manhattan Y U.S. Trust Company 1983 770 Broadway Manhattan Y Ford Foundation 1983 320 43rd Street Manhattan Y The Shoreham 1983 33 W 52nd Street Manhattan Y MacMillen & Co 1983 Manhattan Manhattan * Solomon R Gugenheim 1983 1071 5th Avenue Manhattan * Museum American Bell (ATTIS) 1983 1 Penn Plaza, 2nd Floor Manhattan Y NYC Office of Prosecution 1983 80 Center Street, 6th Floor Manhattan Y Mc Hugh, Leonard & O'Connor 1983 Manhattan Manhattan * Keene Corporation 1983 757 3rd Avenue Manhattan Y Melhado, Flynn & Assocs. 1983 530 5th Avenue Manhattan Y Argentine Consulate 1983 12 W 56th Street Manhattan Y Carol Management 1983 122 E42nd St Manhattan Y Chemical Bank 1983 277 Park Avenue, 2nd Floor Manhattan Y Merrill Lynch 1983 55 Water Street, Floors 36 & 37 Manhattan Y WNET Channel 13 1983 356 W 58th Street Manhattan Y Hotel President (Best Western) 1983 234 W 48th Street Manhattan Y First Boston Corp 1983 5 World Trade Center Manhattan Y Ruffa & Hanover, P.C. -

The BG News January 31, 1986

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 1-31-1986 The BG News January 31, 1986 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News January 31, 1986" (1986). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4479. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4479 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Lone senior anchors gymnastics team, p.8 THE BG NEWS Vol. 68 Issue 73 Bowling Green, Ohio Friday, January 31,1986 Residents complain about noise, litter by Zora Johnson because of peace and litter prob- determine if there is a prob- band and wife signatures on the citations for selling to minors, Marsden, a Popular Culture pro- staff reporter lems. lem." Cetition and some were illegi- then the city could object." fessor, declined comment on the The notice of complaint was Under Ohio law. all liquor Ic," Blair said. "The biggest But Jim Davidson, Ward 1 petition. If some city residents get their filed because Patrick Crowley, licenses expire on October 1, at complaint was noise made by councilman, said he thinks the Pape said he was stunned to way, dinner at Mark's Pizza Pub city attorney, said he did not which time they may either be patrons leaving the establish- petition could cause the city to hear about the complaints.