Don't Put My Article Online: Extending Copyright's New-Use Doctrine to the Electronic Publishing Media and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jennifer Mankoff

185 Stevens Way Jennifer Manko ff Seattle, WA, USA H +1 (412) 567 7720 B Richard E. Ladner Professor jmanko [email protected] Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering Í make4all.org University of Washington jcmanko ff My research focuses on accessibility, health and inclusion. My work combines critical thinking and technological innovation. I strive to bring both structural and personal perspectives to my work. Integrating computational approaches with human-centered analytics, I develop tools that can influence energy saving behavior, provide support for individuals with chronic illnesses and design 3D-printed assistive technologies for people with disabilities. Education 2001 PhD, Georgia Institute of Technology, College of Computing , Atlanta, GA, Thesis Advisors Gregory Abowd and Scott Hudson. Thesis: “An architecture and interaction techniques for handling ambiguity in recognition based input” 1995 B.A., Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH, High Honors. Thesis Advisor: Rhys Price-Jones. Thesis: ”IIC: Information in context” Experience University of Washington 2017–present Richard E. Ladner Professor, Allen School, University of Washington 2020–present Aÿliate Faculty Member, Disability Studies, University of Washington 2020-present Adjunct Faculty Member, iSchool, University of Washington 2019–present Adjunct Faculty Member, HCDE, University of Washington Carnegie Mellon 2016–2017 Professor, HCI Institute, Carnegie Mellon, Pittsburgh, PA. 2015–2017 Aÿliate Faculty Member, ECE , Carnegie Mellon, Pittsburgh, PA. 2008-2016 Associate Professor, HCI Institute, Carnegie Mellon, Pittsburgh, PA. 2004–2008 Assistant Professor, HCI Institute, Carnegie Mellon, Pittsburgh, PA. Consulting and Sabbaticals 2014–2017 Consultant, Disney, Pittsburgh, PA. 2014–2017 Consultant, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center , Cincinnati, OH. 2014–2017 Visiting Professor, ETH, Zrich, CH. -

A Clash of Interests Over the Electronic Encryption Standard

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 1995 A Puzzle Even the Codebreakers Have Trouble Solving: A Clash of Interests over the Electronic Encryption Standard Sean Flynn Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Communications Law Commons, Computer Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons A PUZZLE EVEN THE CODEBREAKERS HAVE TROUBLE SOLVING: A CLASH OF INTERESTS OVER THE ELECTRONIC ENCRYPTION STANDARD SEAN M. FLYNN* I. INTRODUCTION On February 9, 1994, when the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) announced the federal Escrowed Encryption Stan- dard (EES),' the simmering debate over encryption policy in the United States boiled over. Public interest groups argued that the standard would jeopardize an individual's right to privacy. U.S. multinationals voiced concerns that the government would undercut private encryption technology and limit their choice of encryption products for sensitive transmissions. Computer software groups claimed that EES lacked commercial appeal and would adversely affect their ability to compete. Pitted against these concerns were those of the law enforcement and national security communities, which countered that the interests of national security required the adoption of EES. A quick study2 of EES reveals little that would explain this uproar. The NIST issued EES as an encryption methodology for use in its government information processing 3 pursuant to the Computer Secu- rity Act of 1987. 4 The EES is intended to supersede the existing government standard, Data Encryption Standard (DES), which has been in use since 1977 and is very popular. -

The E-Government Act: Promoting E-Quality Or Exaggerating the Digital Divide?

THE E-GOVERNMENT ACT: PROMOTING E-QUALITY OR EXAGGERATING THE DIGITAL DIVIDE? In passing the E-Government Act of 2002, Congress has promised to improve the technological savvy of federal agencies and make more public forms and records available online. However, the question is whether doing so will alienate those Americans who do not have Internet access. Will the Act exaggerate the gap between the Internet haves and have-nots that is known as the digital divide? This iBrief identifies the e- quality issues arising from the E-Government Act and argues that implementation of the Act, however well intentioned, may exaggerate the digital divide. Introduction E-commerce has expanded dramatically in recent years. For example, in the third quarter of 2002 Internet purchases topped $11 billion, an increase of thirty-four percent from the same quarter in 2001.1 The explosion of online information and transactional capabilities is attributable to the benefits the Internet offers to both consumers and businesses. American consumers have become more comfortable with the virtual marketplace as they have learned that they can lower their search costs by using the Internet as a concentrated location for researching products, comparing prices, and making purchases. Likewise, businesses have found that the Internet can be a strong marketing tool, allowing them to save money by decreasing transaction costs and facilitating quick and easy dissemination of product information. Additionally, because websites can be accessed any time of the day, any day of the week, the traditional limitation of business hours no longer applies. The federal government has been slower than private industry in capitalizing on the benefits of e-commerce. -

CA - FACTIVA - SP Content

CA - FACTIVA - SP Content Company & Financial Congressional Transcripts (GROUP FILE Food and Drug Administration Espicom Company Reports (SELECTED ONLY) Veterinarian Newsletter MATERIAL) (GROUP FILE ONLY) Election Weekly (GROUP FILE ONLY) Health and Human Services Department Legal FDCH Transcripts of Political Events Military Review American Bar Association Publications (GROUP FILE ONLY) National Endowment for the Humanities ABA All Journals (GROUP FILE ONLY) General Accounting Office Reports "Humanities" Magazine ABA Antitrust Law Journal (GROUP FILE (GROUP FILE ONLY) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and ONLY) Government Publications (GROUP FILE Alcoholism's Alcohol Research & ABA Banking Journal (GROUP FILE ONLY): Health ONLY) Agriculture Department's Economic National Institute on Drug Abuse NIDA ABA Business Lawyer (GROUP FILE Research Service Agricultural Outlook Notes ONLY) Air and Space Power Journal National Institutes of Health ABA Journal (GROUP FILE ONLY) Centers for Disease Control and Naval War College Review ABA Legal Economics from 1/82 & Law Prevention Public Health and the Environment Practice from 1/90 (GROUP FILE ONLY) CIA World Factbook SEC News Digest ABA Quarterly Tax Lawyer (GROUP FILE Customs and Border Protection Today State Department ONLY) Department of Energy Documents The Third Branch ABA The International Lawyer (GROUP Department of Energy's Alternative Fuel U.S. Department of Agricultural FILE ONLY) News Research ABA Tort and Insurance Law Journal Department of Homeland Security U.S. Department of Justice's -

United States Patent (10) Patent N0.: US 6,173,311 B1 Hassett Et Al

US006173311B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent N0.: US 6,173,311 B1 Hassett et al. (45) Date of Patent: *Jan. 9, 2001 (54) APPARATUS, METHOD AND ARTICLE OF FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS MANUFACTURE FOR SERVICING CLIENT 0113022 11/1984 (EP) REQUESTS ON A NETWORK 0206565 12/1986 (EP) 2034995 6/1980 (GB) (75) Inventors: Gregory P. Hassett, Cupertino, CA 2141907 1/1985 (GB) (US); Harry Collins, South Orange, NJ 2185670 7/1987 (GB) (US); Vibha Dayal, Saratoga, CA (US) 2207314 1/1989 (GB) 2256549 12/1992 (GB) (73) Assignee: PointCast, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA (US) 2281434 3/1995 (GB) 88/04507 6/1988 (WO) ( * ) Notice: This patent issued on a continued pros 90/07844 7/1990 (WO) ecution application ?led under 37 CFR 92/12488 7/1992 (WO) 93/09631 5/1993 (WO) 1.53(d), and is subject to the tWenty year 93/19427 9/1993 (WO) patent term provisions of 35 U.S.C. 95/31069 11/1995 (WO) 154(a)(2). 96/30864 10/1996 (WO) 96/34466 10/1996 (WO) Under 35 U.S.C. 154(b), the term of this patent shall be extended for 0 days. OTHER PUBLICATIONS Appl. No.: 08/800,153 Article, “There’s more to one—Way addressability than meets (21) the eye”. (22) Filed: Feb. 13, 1997 Article, “VCR Technology”, No. 4 in a series of reports from Mitsubishi R&D, Video RevieW, Jan. 1989. (51) Int. Cl.7 .................................................... .. G06F 15/16 Article, “DIP II”, The Ultimate Program Guide Unit from the ultimate listings company. (52) US. Cl. ......................... .. 709/202; 709/217; 709/105 K. -

Juveniles and Computers: Should We Be Concerned?

Juveniles and Computers: Should We Be Concerned? BY ARTHUR L. BOWKER, M.A. Computer Crime Information Coordinator, Northern District of Ohio UVENILE DELINQUENCY and its rehabilitation have There are also signs that computer delinquents are hav- been studied extensively over the years. Much of the ing an impact on state juvenile justice systems. Consider the Jinterest in this topic has centered around the possible following cases: escalation of delinquent acts into adult criminal behavior • A 16-year-old in Chesterland County, Virginia pleaded and the impact of delinquent acts on society, particularly guilty to computer trespassing for hacking into a violent and drug offenses. Federal corrections have not Massachusetts Internet provider’s system, causing been as focused on juvenile delinquency as in years past, $20,000 in damages (Richmond Times-Dispatch, June due in large part to the small number of federal juvenile 25, 1999). offenders. The advent of the computer delinquent* may change many of the concepts of juvenile offenses and reha- • Two youths, ages 14 and 17, pleaded guilty to charges bilitation, including the lack of federal interest. Consider for that they scanned real money and printed counterfeit a moment the following comments of U.S. Attorney for the money in Bedford County, Virginia (Roanoke Times & District of Massachusetts Donald Stern: World News, May 28, 1999). Computer and telephone networks are at the heart of vital services • A 13-year-old boy from Pomona, California admitted to provided by the government and private industry, and our critical infra- making threats against a 13-year-old girl with a computer. -

Pu ROM Raw Asser ADAPTER

USOO5987140A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,987,140 Rowney et al. (45) Date of Patent: Nov. 16, 1999 54 SYSTEM, METHOD AND ARTICLE OF 5,420,405 5/1995 Chasek .................................... 235/379 MANUFACTURE FOR SECURE NETWORK Li inued ELECTRONIC PAYMENT AND CREDIT (List continued on next page.) COLLECTION FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS 75 Inventors: Kevin Thomas Bartholomew Rowney, O 172 670 A2 2/1986 European Pat. Off.. San Francisco; Deepak S. Nadig, San O 256 768 A2 2/1988 European Pat. Off.. Jose, both of Calif. O 256 768 A3 2/1988 European Pat. Off.. s O 326 699 8/1989 European Pat. Off.. 73 Assignee: VeriFone, Inc., Santa Clara, Calif. O 363 122 A3A2 4/1990 European Pat. Off.. O 416 482 3/1991 European Pat. Off.. 21 Appl. No.: 08/639,909 O 527 639 2/1993 European Pat. Off.. 1-1. O 256 768 B1 3/1994 European Pat. Off.. 22 Filed: Apr. 26, 1996 O 363 122 B1 12/1994 European Pat. Off.. 51 Int. Cl. 6 ................................. HO4L 990, Host 90 O 666658 681862 8/19956/1995 European Pat. Off.. 52 U.S. Cl. ................................... 380/49; 380/9; 380/23; O 668 579 8/1995 European Pat. Off.. 380/24; 380/25; 380/28; 380/30; 395/156; 2 251 098 6/1992 United Kingdom 395/18701; 705/26; 705/35; 705/39 WO 91/16691. 10/1991 WIPO. 58 Field of Search .................................... 380/9, 23, 24, WO 93/08545 4/1993 WIPO. 380/25, 48, 49, 50, 59, 28, 30; 705/26, 27, 35, 39, 40, 44; 395/186, 187.01 OTHER PUBLICATIONS Marvin Sirbu et al., “NetBill: An Internet Commerce System 56) References Cited Optimized for Network Delivered Services”; IEEE Comp U.S. -

China's Intellectual Property Protection: Prospects for Achieving International Standards

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 19, Issue 1 1995 Article 8 China’s Intellectual Property Protection: Prospects for Achieving International Standards Derek Dessler∗ ∗ Copyright c 1995 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj China’s Intellectual Property Protection: Prospects for Achieving International Standards Derek Dessler Abstract This Comment presents the intellectual property protection laws of China and examines whether these laws, when combined with the 1995 Accord, will lead to improved intellectual property pro- tection in China. Part I discusses the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs), and the established standards for intellectual property rights protection. Part I also examines China’s intellectual property laws and regulations. Part II analyzes the impediments to effective intellectual property rights enforcement in China. Part III argues that China’s intellectual property rights laws fail to meet the international intellectual property rights standard embodied in TRIPs, and that the 1995 Accord ignores many of the impediments that currently inhibit effective intellectual property protection in China. COMMENTS CHINA'S INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY PROTECTION: PROSPECTS FOR ACHIEVING INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS Derek Dessler* INTRODUCTION Despite China's ancient use of intellectual property and his- tory of technological discoveries and innovations, ' until 1982, it failed to provide any intellectual property protection compara- ble to that found in the United States and other WesternM 2 na- tions.' Since 1982, China has passed new laws,' joined various intellectual property conventions,5 and in February, 1995, signed * J.D. -

Attachment B

Attachment B Cox Enterprises, Inc. Atlanta, GA Broadcast TV: 15 Broadcast Radio: 81 Cable Channels: 7+ Cable Systems: 243 Newspapers: 9 Internet: 26+ Other: 3 Broadcast TV (15 ) Property Location WSB Atlanta, GA WSOC Charlotte, NC WHIO Dayton, OH WFTV Orlando, TV KIRO Seattle, WA KTVU San Francisco/Oakland, CA KICU San Jose/San Francisco, CA WRDQ Orlando, FL WPXI Pittsburgh, PA WAXN Charlotte, NC WJAC-TV Johnstown, PA KFOX-TV El Paso, TX KRXI Reno, NV KAME Reno, NV WTOV Steubenville, OH 1 Broadcast Radio (Cox Radio, Inc.) (81) Property Location WSB-AM Atlanta, GA WSB-FM Atlanta, GA WALR-FM Atlanta, GA WBTS-FM Atlanta, GA WFOX-FM Atlanta, GA WBHJ-FM Birmingham, AL WBHK-FM Birmingham, AL WAGG-AM Birmingham, AL WRJS-AM Birmingham, AL WZZK-FM Birmingham, AL WODL-FM Birmingham, AL WBPT-FM Birmingham, AL WEZN-FM Bridgeport, CT WHKO-FM Dayton, OH WHIO-AM Dayton, OH WDPT-FM Dayton, OH WDTP-FM Dayton, OH WJMZ-FM Greenville, NC WHZT-FM Greenville, NC KRTR-FM Honolulu, HI KXME-FM Honolulu, HI 2 KGMZ-FM Honolulu, HI KCCN-FM Honolulu, HI KINE-FM Honolulu, HI KCCN-AM Honolulu, HI KHPT-FM Houston, TX KLDE-FM Houston, TX KTHT-FM Houston, TX KKBQ-FM Houston, TX WAPE-FM Jacksonville, FL WFYV-FM Jacksonville, FL WKQL-FM Jacksonville, FL WMXQ-FM Jacksonville, FL WOKV-AM Jacksonville, FL WBWL-AM Jacksonville, FL WBLI-FM Long Island, NY WBAB-FM Long Island, NY WHFM-FM Long Island, NY WVEZ-FM Louisville, KY WRKA-FM Louisville, KY WSFR-FM Louisville, KY WPTI-FM Louisville, KY WEDR-FM Miami, FL WHQT-FM Miami, FL 3 WFLC-FM Miami, FL WPYM-FM Miami, FL WPLR-FM New -

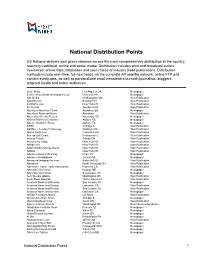

National Distribution Points

National Distribution Points US National delivers your press releases across the most comprehensive distribution in the country, reaching traditional, online and social media. Distribution includes print and broadcast outlets, newswires, online sites, databases and your choice of industry trade publications. Distribution methods include real−time, full−text feeds via the complete AP satellite network, online FTP and content syndicates, as well as personalized email newsletters to reach journalists, bloggers, targeted media and online audiences. 20 de'Mayo Los Angeles CA Newspaper 21st Century Media Newspapers LLC New York NY Newspaper 3BL Media Northampton MA Web Publication 3pointD.com Brooklyn NY Web Publication 401KWire.com New York NY Web Publication 4G Trends Westboro MA Web Publication Aberdeen American News Aberdeen SD Newspaper Aberdeen Business News Aberdeen Web Publication Abernathy Weekly Review Abernathy TX Newspaper Abilene Reflector Chronicle Abilene KS Newspaper Abilene Reporter−News Abilene TX Newspaper ABRN Chicago IL Web Publication ABSNet − Lewtan Technology Waltham MA Web Publication Absolutearts.com Columbus OH Web Publication Access Gulf Coast Pensacola FL Web Publication Access Toledo Toledo OH Web Publication Accounting Today New York NY Web Publication AdAge.com New York NY Web Publication Adam Smith's Money Game New York NY Web Publication Adotas New York NY Web Publication Advance News Publishing Pharr TX Newspaper Advance Newspapers Jenison MI Newspaper Advanced Imaging Pro.com Beltsville MD Web Publication -

Federal Communications Commission FCC 00-202 Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission FCC 00-202 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Applications for Consent to the ) Transfer of Control of Licenses and ) CS Docket No.99-251 Section 214 Authorizations from ) ) MediaOne Group, Inc., ) Transferor, ) ) To ) ) AT&T Corp. ) Transferee ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Adopted: June 5, 2000 Released: June 6, 2000 By the Commission: Chairman Kennard issuing a statement; Commissioner Furchtgott-Roth concurring in part, dissenting in part and issuing a statement; Commissioner Powell concurring and issuing a statement; and Commissioner Tristani concurring and issuing a statement. Table of Contents Paragraph I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………………1 II. PUBLIC INTEREST FRAMEWORK.........................................................................................8 III. BACKGROUND.......................................................................................................................14 A. The Applicants ..............................................................................................................14 B. The Merger Transaction and the Application to Transfer Licenses..................................30 IV. ANALYSIS OF POTENTIAL PUBLIC INTEREST HARMS...................................................35 A. Video Programming.......................................................................................................36 1. Diversity and Competition in Video Program Purchasing ...................................39 -

Computer Crime Review -- 2000

Computer Crime Review -- 2000 Computer Crime: Year 2000 in Review ASIS Cybercrime Summit 2001 M. E. Kabay, PhD, CISSP / Security Leader [email protected] AtomicTangerine, Inc. Wednesday 28 Feb 2001 M. E. Kabay, PhD, CISSP Security Leader [email protected] Marc Goodman Chief Cybercriminologist [email protected] AtomicTangerine, Inc. http://www.atomictangerine.com Copyright © 2001 M. E. Kabay. 1 All rights reserved. Computer Crime Review -- 2000 Computer Crime Update The IYIR project Categories used in IYIR database Today’s presentation – Computer crime cases (Mich Kabay) – Computer forensics issues (Marc Goodman) 2 It may interest the participants that the original version of this extract from the full two-day INFOSEC UPDATE course had 255 slides after the instructor collected them from individual modules dealing with the topics above. See the INFOSEC Year in Review publications for all the cases that were considered. These files will also be available with many other articles and courses by M. E. Kabay in the new K-Files section on SecurityPortal (http://www.securityportal.com). Kabay, M. E. (1997). The INFOSEC Year in Review 1996. http://www.icsa.net/html/library/whitepapers/infosec/InfoSec_Year_in_Review_1996.pdf Kabay, M. E. (1998). The INFOSEC Year in Review 1997. http://www.icsa.net/html/library/whitepapers/infosec/InfoSec_Year_in_Review_1997.pdf Kabay, M. E. (1999). The INFOSEC Year in Review 1998. http://www.icsa.net/html/library/whitepapers/infosec/InfoSec_Year_in_Review_1998.pdf Kabay, M. E. (2000).