'When Everybody There Together … Then I Call That One': Song Order In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

3D Volumetric Modeling with Introspective Neural Networks

The Thirty-Third AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-19) 3D Volumetric Modeling with Introspective Neural Networks Wenlong Huang,*1 Brian Lai,*2 Weijian Xu,3 Zhuowen Tu3 1University of California, Berkeley 2University of California, Los Angeles 3University of California, San Diego Abstract Classification Decision Boundary In this paper, we study the 3D volumetric modeling problem by adopting the Wasserstein introspective neural networks method (WINN) that was previously applied to 2D static im- ages. We name our algorithm 3DWINN which enjoys the same properties as WINN in the 2D case: being simultane- Classification ously generative and discriminative. Compared to the existing Wasserstein 3D volumetric modeling approaches, 3DWINN demonstrates Distance competitive results on several benchmarks in both the genera- tion and the classification tasks. In addition to the standard in- ception score, the Frechet´ Inception Distance (FID) metric is also adopted to measure the quality of 3D volumetric genera- tions. In addition, we study adversarial attacks for volumetric Training Examples CNN Architecture Learned Distribution data and demonstrate the robustness of 3DWINN against ad- Synthesis versarial examples while achieving appealing results in both classification and generation within a single model. 3DWINN is a general framework and it can be applied to the emerging tasks for 3D object and scene modeling.1 Pseudo-negative Distribution Introduction The rich representation power of the deep convolutional neu- Figure 1: Diagram of the Wasserstein introspective neural ral networks (CNN) (LeCun et al. 1989), as a discrimina- networks (adapted from Figure 1 of (Lee et al. 2018)); the tive classifier, has led to a great leap forward for the im- upper figures indicate the gradual refinement over the clas- age classification and regression tasks (Krizhevsky 2009; sification decision boundary between training examples (cir- Szegedy et al. -

Aquaris X2 X2 Pro Complete User Manual

Aquaris X2 (X2 / X2 Pro) Complete User Manual Aquaris X2 / X2 Pro The BQ team would like to thank you for purchasing your new Aquaris X2 / X2 Pro. We hope you enjoy using it. Enjoy the fastest mobile network speeds with this unlocked smartphone thanks to 4G coverage. Its dual-SIM functionality (nano-SIM) means you can use two SIM cards at the same time, even if they are from different operators. You can browse the internet rapidly, check your email, enjoy games and apps (which can be acquired directly from the device), read e-books, transfer files via Bluetooth, record audio, watch films, take photos and record videos, listen to music, chat with your friends and family and enjoy your favourite social networks. It also comes with a fingerprint scanner, enabling you to add a digital fingerprint to unlock your smartphone, authorise purchases or sign in to an application. About this manual · To make sure that you use your smartphone correctly, please read this manual carefully before you start using it. · Some of the images and screenshots shown in this manual may differ slightly from those of the final product. Likewise, due to firmware updates, it is possible that some of the information in this manual does not correspond exactly to the operation of your device. · BQ shall not be held liable for any issues relating to performance or incompatibility resulting from modification of the registry settings by the user. Nor shall it be held liable for any incompatibility issues with third-party applications available through the app stores. -

Script Identification in Printed Bilingual Documents

Script Identification in Printed Bilingual Documents D. Dhanya and A.G. Ramakrishnan Department of Electrical Engineering, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560 012, India [email protected] Abstract. Identification of script in multi-lingual documents is essen- tial for many language dependent applications suchas machinetransla- tion and optical character recognition. Techniques for script identification generally require large areas for operation so that sufficient information is available. Suchassumption is nullified in Indian context, as thereis an interspersion of words of two different scripts in most documents. In this paper, techniques to identify the script of a word are discussed. Two different approaches have been proposed and tested. The first method structures words into 3 distinct spatial zones and utilizes the informa- tion on the spatial spread of a word in upper and lower zones, together with the character density, in order to identify the script. The second technique analyzes the directional energy distribution of a word using Gabor filters withsuitable frequencies and orientations. Words withvar- ious font styles and sizes have been used for the testing of the proposed algorithms and the results obtained are quite encouraging. 1 Introduction Multi-script documents are inevitable in countries housing a national language different from English. This effect is no less felt in India, where as many as 18 regional languages coexist. Many official documents, magazines and reports are bilingual in nature containing both regional language and English. Knowledge of the script is essential in many language dependent processes such as machine translation and OCR. The complexity of the problem of script identification depends on the disposition of the input documents. -

Uncut (Album Review + Mini-Feature, UK, Print, 2013)

NewAlbums THE PENNY DUANE PITRE PURE X BLACK REMEDY Bridges Crawlino Uo lnhale... Exhale... IMPORTANT The Staiis ' A OK, NowYou MEROK/ACEPHALE Can Panic! Just Intonating, brother SOUNDINISTAS - beautiful modern Austinpsychwaffir minimalism getlostinmusic t London-based festival Duane Pitre's career Atatimewhere 6fiO favourites hit cross- 8tlo traiectoryis fair\ 7fiO psychedelic rock is tniry AI cultural sweet spot unique - from professional madeoverinrugged On the followup to TPBR's zoog debut, No Oneb skateboarder through to minimalist composer fashionbyTySegall, Thee OhSees, etel.PM -tr Fault But Your Own, Keith MThomson's is abigleap in somerespects, thoughboth X seem content with being out of time ard m* deadpan compositions often recall the wry do share a love of, to paraphrase minimalist ofphase. Their second album, CrawlingUp Dia worldview of Loudon Wainwright. Emboldened guru La Monte Young, 'drawing a straight IheSfairs, takes a spacier, more ambied byhearty live shows, the dynamicallyprimed line and following it'. OnBridges, Pitre approach, a lava-lamp swirl of effects-selad eh arrangements blendmusic hall, folk and works the mathematical precision of the guitar and bubbling electronics through Balkan influences in a swishlycalibrated Just Intonation tuning systeminto two which frontman Nate Grace's falsetto fl@ fashion. The archness in some of Thomson's side Jong, gorgeously free-fl odting untethered. It is a wispy thing, not alwaprry' topical observations is offset by the sprightly compositions, full of arcing, swooping to gdp. But its more soulful moments canb tempos and welcome brushes of colour. stdngs that accumulate and disperse like quietly transcendent: the languidiazz-ktfr. Melliflous Croatian singer Mariiana tides of fog. -

Ts 136 423 V11.2.0 (2012-10)

ETSI TS 136 423 V11.2.0 (2012-10) Technical Specification LTE; Access Network (E-UTRAN); X2 Application Protocol (X2AP) (3GPP TS 36.423 version 11.2.0 Release 11) 3GPP TS 36.423 version 11.2.0 Release 11 1 ETSI TS 136 423 V11.2.0 (2012-10) Reference RTS/TSGR-0336423vb20 Keywords LTE ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice Individual copies of the present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org The present document may be made available in more than one electronic version or in print. In any case of existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions, the reference version is the Portable Document Format (PDF). In case of dispute, the reference shall be the printing on ETSI printers of the PDF version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at http://portal.etsi.org/tb/status/status.asp If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: http://portal.etsi.org/chaircor/ETSI_support.asp Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced except as authorized by written permission. -

About the Cover

ABOUT THE COVER We are pleased to be continuing our new tradition of having pictures on four pages of the Spirit! In addition to the front and back covers, the alternate sides of these pages capture even more of what was special in 2012. The top picture on the front cover displays the four High Senior Captains of the White Chaos and the Blue Juveniles (left to right): Mitchell Lesser, Matt Shaffer, Danny Brack, and Jacob Stetson holding this year’s Color War plaque. The bottom picture shows many of our fine 2012 staff members getting ready for our always popular Wrestlemania. The inside of the front cover shows an all-star group of 13 year old happy campers (left to right): Aaron Stone, David Rubin, Anthony Shea, Sam Shapiro, Jackson Quist, Jordan Jones, Brett Middleton, Alex Romantz, Ben Burns, Brendan Delaney, Zach Miller, Ari Natansohn, Zach Zysk, and Justin Smith. This is followed below by the camp celebrating after our “House Game” victory over Robin Hood! The inside of the back cover depicts two scenes from West End’s World Cup. On top there is an action shot of the regatta event. This matchup is between South Africa and Brazil. On the bottom, there is a picture of this year’s World Cup Champion Greece, whose flag is now hanging in the dining hall for the entire year. Team members are from left to right front row Brian Barrera, Houston Barenholtz, Kaleb Decker, Noah Leslie, Jacob Denning, Kevin Wu, and Diego Rivera, and back row Farid Mawanda, Coach Mason Williams, and Jacob Stetson. -

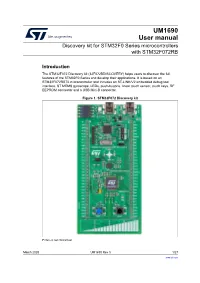

Discovery Kit for STM32F0 Series Microcontrollers with STM32F072RB

UM1690 User manual Discovery kit for STM32F0 Series microcontrollers with STM32F072RB Introduction The STM32F072 Discovery kit (32F072BDISCOVERY) helps users to discover the full features of the STM32F0 Series and develop their applications. It is based on an STM32F072RBT6 microcontroller and includes an ST-LINK/V2 embedded debug tool interface, ST MEMS gyroscope, LEDs, push-buttons, linear touch sensor, touch keys, RF EEPROM connector and a USB Mini-B connector. Figure 1. STM32F072 Discovery kit Picture is not contractual. March 2020 UM1690 Rev 3 1/27 www.st.com Contents UM1690 Contents 1 Features . 6 2 Ordering information . 7 2.1 Product marking . 7 2.2 Codification . 7 3 Development environment . 8 3.1 System requirements . 8 3.2 Development toolchains . 8 3.3 Demonstration software . 8 4 Conventions . 8 5 Hardware layout . 9 5.1 Embedded ST-LINK/V2 . 12 5.1.1 Using ST-LINK/V2 to program/debug the STM32F072 on board . 12 5.1.2 Using ST-LINK/V2 to program/debug an external STM32 application . 13 5.2 Power supply and power selection . 14 5.3 LEDs . 14 5.4 Pushbuttons . 14 5.5 Linear touch sensor / touch keys . 15 5.6 USB device support . 15 5.7 BOOT0 configuration . 15 5.8 Embedded USB Bootloader . 15 5.9 Gyroscope MEMS (ST MEMS I3G4250D) . 16 5.10 JP2 (Idd) . 16 5.11 Extension and RF EEPROM connector . 16 5.12 OSC clock . 18 5.12.1 OSC clock supply . 18 5.12.2 OSC 32 KHz clock supply . 18 5.13 Solder bridges . 19 5.14 Extension connectors . -

(B) Efficient Provision of Public Goods

Public Goods : (b) Efficient Provision of Public Goods Efficiency and Private Goods Suppose that there are only two goods consumed in an economy, and that they are both pure private goods. Suppose as well that there are only two people in the economy. So this is the economy analyzed in intermediate microeconomics (AP/ECON 2300 and 2350), often using the Edgeworth box diagram if the supply of the two goods is fixed.1 However, here the supply of the two goods is not fixed. Instead, there is some production technology in the economy, and some endowment of inputs to production (such as labour and machinery), which determines which combinations of the two goods can be produced. To rep- resent the production possibilities, the production possibility frontier, sometimes called the \production possibility curve" is used, again as in intermediate microeconomics. 1 If X and Y are the total quantities produced of the two goods, the production possibility curve shows the (X; Y ) combinations which are feasible in the economy. This curve could be represented by some equation X = F (Y ) showing the maximum quantity X of food which could be produced, given that we are producing Y units of clothing in the economy. The production possibility frontier slopes down : the more cloth- ing that is produced, the less food which can be produced from the economy's limited resources. So F 0(Y ) < 0 −F 0(Y ) also represents the opportunity cost of clothing, in terms of foregone food. Increasing the economy's clothing production by ∆ units would require the economy to produce −F 0(Y )∆ fewer units of food. -

Dell EMC Xtremio X2: Delivering High Performance and Advanced

Enterprise Strategy Group | Getting to the bigger truth.™ ESG Lab Review Dell EMC XtremIO X2: Delivering High Performance and Advanced Functionality for Virtualized Environments Date: July 2018 Author: Kerry Dolan, Senior IT Validation Analyst Abstract This ESG Lab Review documents testing of the Dell EMC XtremIO X2 array with a focus on high performance and advanced features for today’s modern, virtualized environments. The Challenges There are more technology options than ever before, promising levels of functionality that will truly transform business. But while the vision is exciting, actually delivering is not so easy. The consumerization of IT has led to newly empowered users (as well as senior management) driving functionality requests, believing that anything is possible. This often leaves IT struggling to deliver in reality what the vision promises. It is not surprising, then, that in ESG research, more than two-thirds (68%) of senior IT decision makers believe their organizations’ IT environments are more complex today than two years ago.1 For today’s organizations that focus on virtual servers and desktops, private cloud, and hybrid clouds, this complexity can confound even the best intentions for high performance, simple management, and high availability. Figure 1. IT Complexity In general, how complex is your organization’s IT environment relative to two years ago? (Percent of respondents, N=651) Significantly less complex than two years ago, 1% Significantly more Less complex than two complex than two years years ago, 4% ago, 21% Equally complex as two years ago, 27% More complex than two years ago, 47% Source: Enterprise Strategy Group Virtualized environments are designed to consolidate workloads for infrastructure and management efficiency, but if IT can only deliver efficiency by reducing performance, the tradeoff may not be worth it. -

SONGS to SING!!! 72 1 out of This World! NOTES Song Book

Turn the page for SONGS TO SING!!! 72 1 Out of this World! NOTES Song Book THE AARDVARK SONG………………………………………..………4 APPLES AND BANANAS………………………………………….…5 ARUSTASHA………………………………………………….…....…….5 BABY JAWS………………………………………………………….… 5 BAZOOKA BUBBLE GUM…………………………………………....6 BANANAS, COCONUTS, AND GRAPES…..………………...………7 BANANA SONG…………………………………………….………..….7 BLACK SOCKS………………………………………………………....7 BEAVER CALL………………………………………………………....8 THE BOA CONSTRICTOR…………………………………………..…9 BOOM-CHICKA-BOOM…………………………………………….…10 BROWN EYED GIRL…………………………………………………..11 BUMBLEBEE SONG………………………………………………….12 BUNGALOW……………………………………………………………13 CABIN IN THE WOODS……………………………………………….14 CAN YOU FEEL THE LOVE TONIGHT.……………………………14 CHUGGY CHUGGY….………………………………………………15 CLEAN IT UP BABY……………………………………………………15 CLEAN IT UP BABY (ROCK VERSION)……………………………16 DAY-O……………………………………………………………………17 DESPERADO………..…………………………………………………18 DOWN BY THE BAY…..………………………………………….……19 GOODNIGHT SONG….……………………………………….………20 GOOD RIDDANCE (TIME OF YOUR LIFE)………………………...21 HANDS ON MY SHELL……………………………………………….21 HERE COMES THE SUN……………………………………………...22 HERMIE THE WORM…………………………………………………23 HI, MY NAME IS JOE…………………………………………………25 HUMPTY DUMP……………………………………………………..…26 I DON’T WANT TO LIVE ON THE MOON…………………………27 I’M COMING OUT OF MY SHELL………………………………….28 JET PLANE………………………………………………………………30 2 71 NOTES LEAN ON ME……….……………………………………………….…31 THE LION SLEEPS TONIGHT….….………………………………..32 THE LITTLEST WORM……………………………………………..…33 MOMMA DON’T WEAR NO SOCKS………………………………34 HIGH HEELS…………………………………………………………35 HAVE FUN, BE YOURSELF……………………........................... -

2018 Edition

2018 Edition JCC Ranch Camp, 21441 North Elbert Road, Elbert, CO 80106 Summer Office: 303-648-3800 [email protected] www.ranchcamp.org Rav todot, many thanks, to Carly Coons for recognizing that it was time for an update to our Ranch Camp songbook. With popular hits of its time becoming less familiar, and newer favorites missing, a new compilation was in order. Our songbook nonetheless provided an excellent foundation upon which to build. We would be remiss not to credit Matt Cohen, Polly Hall, and Dan Yolles for their work, which remains the single largest contribution to the current edition. Deepest thanks to those that contributed their time and feedback to this collection. Brynn Tully, Amy Stein Miller, Amalia Ritter, Dan Yolles, and Debra Winter put thought and spirit into the production of this book, including meticulous chord notation. It must be said that this songbook is “Tam v’lo nishlam,” finished, but not yet complete. Brynn and Carly will be tasked with implementing this collection over the course of Summer 2018 with the goal of producing a final edition after integrating feedback from our Ranch Camp Kehila. L’Shalom, Noah Gallagher Ranch Camp Director JCC Ranch Camp Songbook 3 ADAMAH V’SHAMAYIM – Segev Chorus (X2) Em Bm G Heya Heya Heya Heya Heya Heya Heya Ho (X2) Love is all you need G D C D Em G Heya Heya Heya Heya Heya Heya Heya Ho! Love is all you need (repeat till end) Em Bm Adamah… V’shamayim… AM I AWAKE? – Noah Aronson Em Bm Capo 2-3 Chom Ha’eish… Tzlil Hamayim… G D Ya la lai lai lai… Ani Margish Zot B’gufi