Bus Planning Literature Review - Research and Report by JRC Ltd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobility on Demand (MOD) Sandbox: Vermont Agency of Transportation (Vtrans) Flexible Trip Planner, Final Report

Mobility on Demand (MOD) Sandbox: Vermont Agency of Transportation (VTrans) Flexible Trip Planner Final Report JANUARY 2020 FTA Report No. 0150 Federal Transit Administration PREPARED BY Ross MacDonald Program Manager, Go! Vermont Public Transit Coordinator Vermont Agency of Transportation COVER PHOTO Image courtesy of Edwin Adilson Rodriguez, Federal Transit Administration DISCLAIMER This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products of manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Mobility on Demand (MOD) Sandbox: Vermont Agency of Transportation (VTrans) Flexible Trip Planner Final Report JANUARY 2020 FTA Report No. 0150 PREPARED BY Ross MacDonald Public Transit Coordinator Vermont Agency of Transportation Public Transit Section 219 North Main Street Barre, VT 05641 SPONSORED BY Federal Transit Administration Office of Research, Demonstration and Innovation U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590 AVAILABLE ONLINE https://www.transit.dot.gov/about/research-innovation FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION i Metric Conversion Table SYMBOL WHEN YOU KNOW MULTIPLY BY TO FIND SYMBOL LENGTH in inches 25.4 millimeters mm ft feet 0.305 meters m yd yards 0.914 meters m mi miles 1.61 kilometers km VOLUME fl oz fluid ounces 29.57 milliliters mL gal gallons 3.785 liters L 3 3 ft cubic feet 0.028 cubic meters m 3 3 yd cubic yards 0.765 cubic meters m NOTE: volumes greater than 1000 L shall be shown in m3 MASS oz ounces 28.35 grams g lb pounds 0.454 kilograms kg megagrams T short tons (2000 lb) 0.907 Mg (or "t") (or "metric ton") TEMPERATURE (exact degrees) o 5 (F-32)/9 o F Fahrenheit Celsius C or (F-32)/1.8 FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION iv REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. -

Covid-19 Recovery Renewing the Transport System

Covid-19 Recovery Renewing the transport system July 2020 Covid-19 Recovery • Renewing the transport system 1 Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Impact of the crisis 7 Opportunity for renewal 15 Facilitating the shift to a rapid renewal 34 References 36 Acknowledgements This paper was developed by Campaign for Better Transport and is solely its view. Organisations were engaged directly and through four virtual roundtable discussions in May 2020, with senior representatives of train and bus operators, government representatives, local authorities, passenger bodies, technology companies and other stakeholders. Thanks go to the following organisations that were engaged or participated in discussions to inform the contents of this report, including: Abellio Group, Angel Trains, Arriva Group, Avis Budget Group, Bird, Bombardier, Bus Users UK, BVRLA, Cambridge and Peterborough Combined Authority, Client Earth, Community Rail, Community Transport Association, CoMoUK, Confederation of Passenger Transport, Essex County Council, Eversholt Rail, First Group, Five AI, Go-Ahead Group, Grand Central Railway, GTR, HCT Group, Liverpool City Region, Living Streets, Local Government Association, Network Rail, North East Combined Authority, Rail Delivery Group, Rail Freight Group, Rail Industry Association, RSSB, Ryse Hygrogen, South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Executive, Stagecoach Group, Sustrans, The AA, Trainline, Transdev, Transport & Environment, Transport Focus, Transport for Greater Manchester, Transport for London, Transport for the North, Transport for West Midlands, Uber, Urban Transport Group, ViaVan, Wrightbus, Zeelo. The paper has also been peer reviewed by the Campaign for Better Transport Policy Associates Network. Thank you to Isabel Dedring, Jim Steer, Keith Buchan, Kris Beuret, Leon Daniels, Lilli Matson, Lynda Addison, Matt Lovering, Phil Jones, Prof. -

Part 1: Downtown Transit Center and Circulator Shuttle

Howard Research and Development Corporation Downtown Columbia Downtown Transit Center and Circulator Shuttle Feasibility Study: Part 1 - Downtown Transit Center & Downtown Circulator Shuttle (Part of CEPPA #5) DRAFTDecember 2011 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. iv Chapter 1. Downtown Columbia Transit Center ....................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2. Downtown Columbia Circulator Shuttle ............................................................................................... 12 Appendix A. Regional Transit System Evaluation .............................................................................................. 21 Appendix B. Regional Transit Market Analysis .................................................................................................. 46 Appendix C. Transit Circulator Design ................................................................................................................ 64 Appendix D. Transit Center Site Evaluation ...................................................................................................... 764 Appendix E. Transit Development Plan ............................................................................................................... 79 DRAFT Page i• Nelson\Nygaard Consulting Associates Inc. Table of Figures Figure 1 Existing -

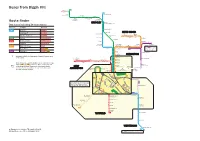

Buses from Biggin Hill

Buses from Biggin Hill 320 Catford and Catford Bridge 246 Catford Bromley North Lewisham Town Hall Downham Old Bromley Road Bromley Hill Catford Southend Village Bus Garage The Pond Bromley Route finder for Bellingham Market Square BROMLEY Bromley Day buses including 24-hour routes The Glades Shopping Centre Bus route Towards Bus stops Bromley South 246 Bromley ,s ,t ,w Masons Hill PETTS WOOD Chartwell 0 ,n ,p ,r Cameron Road Amherst Bromley Common Petts Wood Drive Westerham Green ,n ,p ,r Crown R2 Petts Wood Hail & Ride Pickhurst Lane Road section Catford ,a ,b ,c ,v ,w Kent Road 320 Oakley Road New Addington ,b ,c ,h ,v ,w Hayes Orpington 464 Walnuts Centre (High Street) Tats eld ,d ,e ,f ,n Coney Hall Locksbottom Orpington Orpington Addington Road Princess Royal War Memorial Walnuts Centre (Homeeld Rise) Biggin Hill Valley ,a ,n University Hospital Orpington R2 Route R8 does not serve Keston Crofton Road Orpington Walnuts Centre Petts Wood ,v ,w H&R2 Fox Keston Mark R8 during early mornings on Mondays to Fridays Orpington ,s ,t ,w H&R1 Keston R8 Church Orpington Hospital Leaves Green King's Arms ORPINGTON 0 Sundays and Public Holidays when Chartwell House is open Biggin Hill Airport to the public. Green Street Green New Addington Addington Parkway High School Salt Box Hill Main Road Hanbury Drive 464 Homestead Jewels Hill Hail & Ride section Way Main Road Route R8 operates as Hail and Ride on the sections of roads Salt Box Hill H&R1 H&R2 Downe marked and on the map. Buses stop at any safe St. -

Vermont Public Transit Policy Plan

TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................. ES-1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ ES-1 Vermont’s Existing Transit System ................................................................................................................. ES-1 Critical Themes and Challenges ....................................................................................................................... ES-1 Needs Assessment ............................................................................................................................................. ES-2 Policy Plan Recommendations ......................................................................................................................... ES-3 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 1 Role of the PTPP ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 Current State Policy .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Role of the Human Service Transportation Coordination Plan -

Impact Report 2007/08 Published 2009 Welcome

Impact Report 2007/08 Published 2009 Welcome Contents Meet HCT Group 04 Changing lives and communities 16 Commercial success 08 Employment, learning and skills 0 Engaging stakeholders 14 The road ahead 24 HCT Group is an excellent example of how social enterprise Welcome can benefit local communities and the economy. In times of economic hardship, such HCT Group is in the transport business. We run a commercially businesses are to be applauded successful operation, generating a healthy income from safely for providing much needed delivering more than 27,500 passenger trips every day. services to users with mobility difficulties, and for boosting But this only tells part of our story. HCT is first and foremost a local community investment social enterprise, which is why we have published this Impact and employment. Report. The following pages are designed to provide an insight into our commercial and social impact over the last few years. Chris Huhne HCT is a fantastic organisation. Liberal Democrat shadow The passion with which they Most of the facts and figures in this report relate to an 18-month Home Secretary combine their commercial work period between April 2007 and September 2008. However, some with their social mission is to be financial statements, including those relating to growth and admired. Social enterprise will profitability, cover the financial years of 2006/07 and 2007/08. Social enterprises can help us play an increasing role in our deliver better public services and economy in the coming years. As this report demonstrates, the core of our business is create local jobs at the same time. -

The Art of the Possible in Public Procurement Frank Villeneuve-Smith and Julian Blake 3

The art of the possible in public procurement Frank Villeneuve-Smith and Julian Blake 3 About the authors Acknowledgements Frank Villeneuve-Smith is the Director Bates Wells Braithwaite, HCT Group of Communications at HCT Group – and E3M would like to thank Geetha a transport social enterprise. In addition to Rabindrakumar and her colleagues over 20 years’ senior marketing experience, at Big Society Capital, Adam Kybird at he specialises in bringing complex topics Bridges Ventures and Adam Swersky to life for a wide range of audiences. at Social Finance for their ideas and He is the author or co-author of a score introductions for case studies – as well of publications on subjects ranging from as all the colleagues at commissioning transport procurement to employability authorities and providers who gave Introduction skills, from CPD strategy in Further so generously of their time, providing Education colleges to the biennial State of feedback on content, telling their stories An end to pushing on Social Enterprise survey for SEUK. and contributing cases. The authors would also like to thank David Hunter, Dai Powell a piece of string Julian Blake is co-head of Social Enterprise and Jonathan Bland for their advice and and Charity at Bates Wells Braithwaite support during the project. public benefit lawyers. He has engaged with public service commissioning for 25 years, through: the ‘contract culture’; ‘fair contract’ and ‘full cost recovery’ campaigns; and the development of Social Enterprise, Social Finance and spin-out mutuals. He promotes the European Commission Social Business Initiative perspective on Public Procurement and State Aid, challenging misconceptions. -

Mod Innovative Practices

Mobility on Demand Strategic Plan Humboldt County MoD Innovative Practices TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM DRAFT – For Discussion Prepared for HCAOG by IBI Group October 2019 IBI GROUP MOD INNOVATIVE PRACTICES Prepared for HCAOG Table of Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Document Organization ........................................................................................... 4 1.3 Sources .................................................................................................................... 5 2 Mobility Landscape in North America .............................................................................. 7 2.1 Factors Driving Change ........................................................................................... 7 2.2 Mobility Solutions and Suppliers .............................................................................. 9 3 Emerging Role of Transit Agencies ................................................................................ 11 3.1 Business Models .................................................................................................... 11 3.1.1 Mobility on Demand .................................................................................. 11 3.1.2 Family of Services .................................................................................... -

Badgerline Merger Undertakings Review

5HYLHZRI)LUVW*URXS EXVXQGHUWDNLQJVLQ %ULVWRO )LQDOGHFLVLRQ -XO\ © Crown copyright 2017 You may reuse this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Website: www.gov.uk/cma Members of the Competition and Markets Authority who are conducting this review Simon Polito (Chair of the Group) Anne Lambert Sarah Chambers Chief Executive of the Competition and Markets Authority Andrea Coscelli (acting Chief Executive) The Competition and Markets Authority has excluded from this published version of the provisional decision report information which the CMA considers should be excluded having regard to the three considerations set out in section 244 of the Enterprise Act 2002 (specified information: considerations relevant to disclosure). The omissions are indicated by []. Contents Page Summary .................................................................................................................... 2 Final decision ........................................................................................................ 4 Final decision ............................................................................................................. 6 1. Introduction and background ............................................................................... -

From the Chair

From the Chair OFFICE OF THE ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON BUSINESS APPOINTMENTS G/7 Ground Floor, 1 Horse Guards Road SW1A 2HQ Telephone: 020 7271 0839 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.Gov.uk/aCoba July 2016 You asked for the Committee’s advice about accepting a part-time, unpaid role as non- executive Chair of HCT Group, a social enterprise bus operator. HCT Group operates across London, Yorkshire, Humberside, the Southwest and the Channel Islands, and has a fleet of 500 vehicles. It provides a range of transport-related services including London red buses, social services transport, school transport, Park and Ride, and education and training. The Committee sought the opinion of your former department, BIS, which did not have any concerns regarding the propriety of this appointment, as they are not aware of any relationship with HCT. The Committee noted BIS’s view that any contact between HCT and Government is likely to be between the organisation and the Department for Transport, and would refer you to the terms of the lobbying restriction set out below. Taking into account the specific facts in this case, the Committee sees no reason why you should not take up the appointment, subject to the following conditions: ● That you should not draw on (disclose or use for the benefit of yourself or the organisation to which this advice refers) any privileged information available to you as a Minister; and ● For two years from your last day in ministerial office, you should not become personally involved in lobbying the UK Government on behalf of HCT Group. -

Access to Transport for Disabled People

House of Commons Transport Committee Access to transport for disabled people Fifth Report of Session 2013–14 Volume I Volume I: Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Additional written evidence is contained in Volume II, available on the Committee website at www.parliament.uk/transcom Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 9 September 2013 HC 116 [Incorporating HC 1002, Session 2012-13] Published on 17 September 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £22.00 The Transport Committee The Transport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Transport and its Associate Public Bodies. Current membership Mrs Louise Ellman (Labour/Co-operative, Liverpool Riverside) (Chair) Sarah Champion (Labour, Rotherham) Jim Dobbin (Labour/Co-operative, Heywood and Middleton) Karen Lumley (Conservative, Redditch) Jason McCartney (Conservative, Colne Valley) Karl McCartney (Conservative, Lincoln) Lucy Powell (Labour/Co-operative, Manchester Central) Mr Adrian Sanders (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Iain Stewart (Conservative, Milton Keynes South) Graham Stringer (Labour, Blackley and Broughton) Martin Vickers (Conservative, Cleethorpes) The following were also members of the committee during the Parliament. Steve Baker (Conservative, Wycombe), Angie Bray (Conservative, Ealing Central and Acton), Lilian Greenwood (Labour, Nottingham South), Mr Tom Harris (Labour, Glasgow South), Julie Hilling (Labour, Bolton West), Kelvin Hopkins (Labour, Luton North), Kwasi Kwarteng (Conservative, Spelthorne), Mr John Leech (Liberal Democrat, Manchester Withington) Paul Maynard, (Conservative, Blackpool North and Cleveleys), Gavin Shuker (Labour/Co-operative, Luton South), Angela Smith (Labour, Penistone and Stocksbridge), Julian Sturdy (Conservative, York Outer) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

WAVE SHORT RANGE TRANSIT PLAN Final Report

Cape Fear Public Transportation Authority WAVE SHORT RANGE TRANSIT PLAN Final Report June 2012 SHORT RANGE TRANSIT PLAN | FINAL REPORT CAPE FEAR PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY Table of Contents Page 1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 5 2 Overview and Study Approach .......................................................................................... 7 3 Existing Service ................................................................................................................... 9 Passenger Facilities ................................................................................................................................. 14 Fares ........................................................................................................................................................... 15 Existing Plans and Studies ...................................................................................................................... 15 Agency Goals and Objectives .............................................................................................................. 16 4 Stakeholder and Public Input ............................................................................................ 19 Rider and Non-Rider Survey ................................................................................................................. 19 Stakeholder Interviews ..........................................................................................................................