Geometry of Crystal Lattice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conway Space-Filling

Symmetry: Art and Science Buenos Aires Congress, 2007 THE CONWAY SPACE-FILLING MICHAEL LONGUET-HIGGINS Name: Michael S. Longuet-Higgins, Mathematician and Oceanographer, (b. Lenham, England, 1925). Address: Institute for Nonlinear Science, University of California San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92037-0402, U.S.A. Email: [email protected] Fields of interest: Fluid dynamics, ocean waves and currents, geophysics, underwater sound, projective geometry, polyhedra, mathematical toys. Awards: Rayleigh Prize for Mathematics, Cambridge University, 1950; Hon.D. Tech., Technical University of Denmark, 1979; Hon. LL.D., University of Glasgow, Scotland, 1979; Fellow of the American Geophysical Union, 1981; Sverdrup Gold Medal of the American Meteorological Society, 1983; International Coastal Engineering Award of the American Society of Civil Engineers, 1984; Oceanography Award of the Society for Underwater Technology, 1990; Honorary Fellow of the Acoustical Society of America, 2002. Publications: “Uniform polyhedra” (with H.S.M. Coxeter and J.C.P. Miller (1954). Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 246, 401-450. “Some Mathematical Toys” (film), (1963). British Association Meeting, Aberdeen, Scotland; “Clifford’s chain and its analogues, in relation to the higher polytopes,” (1972). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 330, 443-466. “Inversive properties of the plane n-line, and a symmetric figure of 2x5 points on a quadric,” (1976). J. Lond. Math. Soc. 12, 206-212; Part II (with C.F. Parry) (1979) J. Lond. Math. Soc. 19, 541-560; “Nested triacontahedral shells, or How to grow a quasi-crystal,” (2003) Math. Intelligencer 25, 25-43. Abstract: A remarkable new space-filling, with an unusual symmetry, was recently discovered by John H. -

Crystal Structure of a Material Is Way in Which Atoms, Ions, Molecules Are Spatially Arranged in 3-D Space

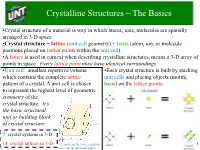

Crystalline Structures – The Basics •Crystal structure of a material is way in which atoms, ions, molecules are spatially arranged in 3-D space. •Crystal structure = lattice (unit cell geometry) + basis (atom, ion, or molecule positions placed on lattice points within the unit cell). •A lattice is used in context when describing crystalline structures, means a 3-D array of points in space. Every lattice point must have identical surroundings. •Unit cell: smallest repetitive volume •Each crystal structure is built by stacking which contains the complete lattice unit cells and placing objects (motifs, pattern of a crystal. A unit cell is chosen basis) on the lattice points: to represent the highest level of geometric symmetry of the crystal structure. It’s the basic structural unit or building block of crystal structure. 7 crystal systems in 3-D 14 crystal lattices in 3-D a, b, and c are the lattice constants 1 a, b, g are the interaxial angles Metallic Crystal Structures (the simplest) •Recall, that a) coulombic attraction between delocalized valence electrons and positively charged cores is isotropic (non-directional), b) typically, only one element is present, so all atomic radii are the same, c) nearest neighbor distances tend to be small, and d) electron cloud shields cores from each other. •For these reasons, metallic bonding leads to close packed, dense crystal structures that maximize space filling and coordination number (number of nearest neighbors). •Most elemental metals crystallize in the FCC (face-centered cubic), BCC (body-centered cubic, or HCP (hexagonal close packed) structures: Room temperature crystal structure Crystal structure just before it melts 2 Recall: Simple Cubic (SC) Structure • Rare due to low packing density (only a-Po has this structure) • Close-packed directions are cube edges. -

Types of Lattices

Types of Lattices Types of Lattices Lattices are either: 1. Primitive (or Simple): one lattice point per unit cell. 2. Non-primitive, (or Multiple) e.g. double, triple, etc.: more than one lattice point per unit cell. Double r2 cell r1 r2 Triple r1 cell r2 r1 Primitive cell N + e 4 Ne = number of lattice points on cell edges (shared by 4 cells) •When repeated by successive translations e =edge reproduce periodic pattern. •Multiple cells are usually selected to make obvious the higher symmetry (usually rotational symmetry) that is possessed by the 1 lattice, which may not be immediately evident from primitive cell. Lattice Points- Review 2 Arrangement of Lattice Points 3 Arrangement of Lattice Points (continued) •These are known as the basis vectors, which we will come back to. •These are not translation vectors (R) since they have non- integer values. The complexity of the system depends upon the symmetry requirements (is it lost or maintained?) by applying the symmetry operations (rotation, reflection, inversion and translation). 4 The Five 2-D Bravais Lattices •From the previous definitions of the four 2-D and seven 3-D crystal systems, we know that there are four and seven primitive unit cells (with 1 lattice point/unit cell), respectively. •We can then ask: can we add additional lattice points to the primitive lattices (or nets), in such a way that we still have a lattice (net) belonging to the same crystal system (with symmetry requirements)? •First illustrate this for 2-D nets, where we know that the surroundings of each lattice point must be identical. -

The Metrical Matrix in Teaching Mineralogy G. V

THE METRICAL MATRIX IN TEACHING MINERALOGY G. V. GIBBS Department of Geological Sciences & Department of Materials Science and Engineering Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Blacksburg, VA 24061 [email protected] INTRODUCTION The calculation of the d-spacings, the angles between planes and zones, the bond lengths and angles and other important geometric relationships for a mineral can be a tedious task both for the student and the instructor, particularly when completed with the large as- sortment of trigonometric identities and algebraic formulae that are available (d. Crystal Geometry (1959), Donnay and Donnay, International Tables for Crystallography, Vol. II, Section 3, The Kynoch Press, 101-158). However, such calculations are straightforward and relatively easy to do when completed with the metrical matrix and the interactive software MATOP. Several applications of the matrix are presented below, each of which is worked out in detail and which is designed to teach you its use in the study of crystal geometry. SOME PRELIMINARY COMMENTS We begin our discussion of the matrix with a brief examination of the properties of the geometric three dimensional space, S, in which we live and in which minerals and rocks occur. For our purposes, it will be convenient to view S as the set of all vectors that radiate from a common origin to each point in space. In constructing a model for S, we chose three noncoplanar, coordinate axes denoted X, Y and Z, each radiating from the origin, O. Next, we place three nonzero vectors denoted a, band c along X, Y and Z, respectively, likewise radiating from O. -

Primitive Cell Wigner-Seitz Cell (WS) Primitive Cell

Lecture 4 Jan 16 2013 Primitive cell Primitive cell Wigner-Seitz cell (WS) First Brillouin zone The Wigner-Seitz primitive cell of the reciprocal lattice is known as the first Brillouin zone. (Wigner-Seitz is real space concept while Brillouin zone is a reciprocal space idea). Powder cell Polymorphic Forms of Carbon Graphite – a soft, black, flaky solid, with a layered structure – parallel hexagonal arrays of carbon atoms – weak van der Waal’s forces between layers – planes slide easily over one another Miller indices Simple cubic Miller Indices Rules for determining Miller Indices: 1. Determine the intercepts of the face along the crystallographic axes, in terms of un it ce ll dimens ions. 2. Take the reciprocals 3. Clear fractions 4. Reduce to lowest terms Simple cubic d100=? Where does a protein crystallographer see the Miller indices? CtlCommon crystal faces are parallel to lattice planes • Eac h diffrac tion spo t can be regarded as a X-ray beam reflected from a lattice plane , and therefore has a unique Miller index. Miller indices A Miller index is a series of coprime integers that are inversely ppproportional to the intercepts of the cry stal face or crystallographic planes with the edges of the unit cell. It describes the orientation of a plane in the 3-D lattice with respect to the axes. The general form of the Miller index is (h, k, l) where h, k, and l are integers related to the unit cell along the a, b, c crystal axes. Irreducible brillouin zone II II II II Reciprocal lattice ghakblc The Bravais lattice after Fourier transform real space reciprocal lattice normaltthlls to the planes (vect ors ) poitints spacing between planes 1/distance between points ((y,p)actually, 2p/distance) l (distance, wavelength) 2p/l=k (momentum, wave number) BillBravais cell Wigner-SiSeitz ce ll Brillouin zone . -

Chapter 4, Bravais Lattice Primitive Vectors

Chapter 4, Bravais Lattice A Bravais lattice is the collection of all (and only those) points in space reachable from the origin with position vectors: n , n , n integer (+, -, or 0) r r r r 1 2 3 R = n1a1 + n2 a2 + n3a3 a1, a2, and a3 not all in same plane The three primitive vectors, a1, a2, and a3, uniquely define a Bravais lattice. However, for one Bravais lattice, there are many choices for the primitive vectors. A Bravais lattice is infinite. It is identical (in every aspect) when viewed from any of its lattice points. This is not a Bravais lattice. Honeycomb: P and Q are equivalent. R is not. A Bravais lattice can be defined as either the collection of lattice points, or the primitive translation vectors which construct the lattice. POINT Q OBJECT: Remember that a Bravais lattice has only points. Points, being dimensionless and isotropic, have full spatial symmetry (invariant under any point symmetry operation). Primitive Vectors There are many choices for the primitive vectors of a Bravais lattice. One sure way to find a set of primitive vectors (as described in Problem 4 .8) is the following: (1) a1 is the vector to a nearest neighbor lattice point. (2) a2 is the vector to a lattice points closest to, but not on, the a1 axis. (3) a3 is the vector to a lattice point nearest, but not on, the a18a2 plane. How does one prove that this is a set of primitive vectors? Hint: there should be no lattice points inside, or on the faces (lll)fhlhd(lllid)fd(parallolegrams) of, the polyhedron (parallelepiped) formed by these three vectors. -

Lecture Notes

Solid State Physics PHYS 40352 by Mike Godfrey Spring 2012 Last changed on May 22, 2017 ii Contents Preface v 1 Crystal structure 1 1.1 Lattice and basis . .1 1.1.1 Unit cells . .2 1.1.2 Crystal symmetry . .3 1.1.3 Two-dimensional lattices . .4 1.1.4 Three-dimensional lattices . .7 1.1.5 Some cubic crystal structures ................................ 10 1.2 X-ray crystallography . 11 1.2.1 Diffraction by a crystal . 11 1.2.2 The reciprocal lattice . 12 1.2.3 Reciprocal lattice vectors and lattice planes . 13 1.2.4 The Bragg construction . 14 1.2.5 Structure factor . 15 1.2.6 Further geometry of diffraction . 17 2 Electrons in crystals 19 2.1 Summary of free-electron theory, etc. 19 2.2 Electrons in a periodic potential . 19 2.2.1 Bloch’s theorem . 19 2.2.2 Brillouin zones . 21 2.2.3 Schrodinger’s¨ equation in k-space . 22 2.2.4 Weak periodic potential: Nearly-free electrons . 23 2.2.5 Metals and insulators . 25 2.2.6 Band overlap in a nearly-free-electron divalent metal . 26 2.2.7 Tight-binding method . 29 2.3 Semiclassical dynamics of Bloch electrons . 32 2.3.1 Electron velocities . 33 2.3.2 Motion in an applied field . 33 2.3.3 Effective mass of an electron . 34 2.4 Free-electron bands and crystal structure . 35 2.4.1 Construction of the reciprocal lattice for FCC . 35 2.4.2 Group IV elements: Jones theory . 36 2.4.3 Binding energy of metals . -

Introduction to the Physical Properties of Graphene

Introduction to the Physical Properties of Graphene Jean-No¨el FUCHS Mark Oliver GOERBIG Lecture Notes 2008 ii Contents 1 Introduction to Carbon Materials 1 1.1 TheCarbonAtomanditsHybridisations . 3 1.1.1 sp1 hybridisation ..................... 4 1.1.2 sp2 hybridisation – graphitic allotopes . 6 1.1.3 sp3 hybridisation – diamonds . 9 1.2 Crystal StructureofGrapheneand Graphite . 10 1.2.1 Graphene’s honeycomb lattice . 10 1.2.2 Graphene stacking – the different forms of graphite . 13 1.3 FabricationofGraphene . 16 1.3.1 Exfoliatedgraphene. 16 1.3.2 Epitaxialgraphene . 18 2 Electronic Band Structure of Graphene 21 2.1 Tight-Binding Model for Electrons on the Honeycomb Lattice 22 2.1.1 Bloch’stheorem. 23 2.1.2 Lattice with several atoms per unit cell . 24 2.1.3 Solution for graphene with nearest-neighbour and next- nearest-neighour hopping . 27 2.2 ContinuumLimit ......................... 33 2.3 Experimental Characterisation of the Electronic Band Structure 41 3 The Dirac Equation for Relativistic Fermions 45 3.1 RelativisticWaveEquations . 46 3.1.1 Relativistic Schr¨odinger/Klein-Gordon equation . ... 47 3.1.2 Diracequation ...................... 49 3.2 The2DDiracEquation. 53 3.2.1 Eigenstates of the 2D Dirac Hamiltonian . 54 3.2.2 Symmetries and Lorentz transformations . 55 iii iv 3.3 Physical Consequences of the Dirac Equation . 61 3.3.1 Minimal length for the localisation of a relativistic par- ticle ............................ 61 3.3.2 Velocity operator and “Zitterbewegung” . 61 3.3.3 Klein tunneling and the absence of backscattering . 61 Chapter 1 Introduction to Carbon Materials The experimental and theoretical study of graphene, two-dimensional (2D) graphite, is an extremely rapidly growing field of today’s condensed matter research. -

Phys 446: Solid State Physics / Optical Properties

Phys 446: Solid State Physics / Optical Properties Fall 2015 Lecture 2 Andrei Sirenko, NJIT 1 Solid State Physics Lecture 2 (Ch. 2.1-2.3, 2.6-2.7) Last week: • Crystals, • Crystal Lattice, • Reciprocal Lattice Today: • Types of bonds in crystals Diffraction from crystals • Importance of the reciprocal lattice concept Lecture 2 Andrei Sirenko, NJIT 2 1 (3) The Hexagonal Closed-packed (HCP) structure Be, Sc, Te, Co, Zn, Y, Zr, Tc, Ru, Gd,Tb, Py, Ho, Er, Tm, Lu, Hf, Re, Os, Tl • The HCP structure is made up of stacking spheres in a ABABAB… configuration • The HCP structure has the primitive cell of the hexagonal lattice, with a basis of two identical atoms • Atom positions: 000, 2/3 1/3 ½ (remember, the unit axes are not all perpendicular) • The number of nearest-neighbours is 12 • The ideal ratio of c/a for Rotated this packing is (8/3)1/2 = 1.633 three times . Lecture 2 Andrei Sirenko, NJITConventional HCP unit 3 cell Crystal Lattice http://www.matter.org.uk/diffraction/geometry/reciprocal_lattice_exercises.htm Lecture 2 Andrei Sirenko, NJIT 4 2 Reciprocal Lattice Lecture 2 Andrei Sirenko, NJIT 5 Some examples of reciprocal lattices 1. Reciprocal lattice to simple cubic lattice 3 a1 = ax, a2 = ay, a3 = az V = a1·(a2a3) = a b1 = (2/a)x, b2 = (2/a)y, b3 = (2/a)z reciprocal lattice is also cubic with lattice constant 2/a 2. Reciprocal lattice to bcc lattice 1 1 a a x y z a2 ax y z 1 2 2 1 1 a ax y z V a a a a3 3 2 1 2 3 2 2 2 2 b y z b x z b x y 1 a 2 a 3 a Lecture 2 Andrei Sirenko, NJIT 6 3 2 got b y z 1 a 2 b x z 2 a 2 b x y 3 a but these are primitive vectors of fcc lattice So, the reciprocal lattice to bcc is fcc. -

Part 1: Supplementary Material Lectures 1-5

Crystal Structure and Dynamics Paolo G. Radaelli, Michaelmas Term 2014 Part 1: Supplementary Material Lectures 1-5 Web Site: http://www2.physics.ox.ac.uk/students/course-materials/c3-condensed-matter-major-option Contents 1 Frieze patterns and frieze groups 3 2 Symbols for frieze groups 4 2.1 A few new concepts from frieze groups . .5 2.2 Frieze groups in the ITC . .7 3 Wallpaper groups 8 3.1 A few new concepts for Wallpaper Groups . .8 3.2 Lattices and the “translation set” . .9 3.3 Bravais lattices in 2D . .9 3.3.1 Oblique system . 10 3.3.2 Rectangular system . 10 3.3.3 Square system . 10 3.3.4 Hexagonal system . 11 3.4 Primitive, asymmetric and conventional Unit cells in 2D . 11 3.5 The 17 wallpaper groups . 12 3.6 Analyzing wallpaper and other 2D art using wallpaper groups . 12 1 4 Fourier transform of lattice functions 13 5 Point groups in 3D 14 5.1 The new generalized (proper & improper) rotations in 3D . 14 5.2 The 3D point groups with a 2D projection . 15 5.3 The other 3D point groups: the 5 cubic groups . 15 6 The 14 Bravais lattices in 3D 19 7 Notation for 3D point groups 21 7.0.1 Notation for ”projective” 3D point groups . 21 8 Glide planes in 3D 22 9 “Real” crystal structures 23 9.1 Cohesive forces in crystals — atomic radii . 23 9.2 Close-packed structures . 24 9.3 Packing spheres of different radii . 25 9.4 Framework structures . 26 9.5 Layered structures . -

Valleytronics: Opportunities, Challenges, and Paths Forward

REVIEW Valleytronics www.small-journal.com Valleytronics: Opportunities, Challenges, and Paths Forward Steven A. Vitale,* Daniel Nezich, Joseph O. Varghese, Philip Kim, Nuh Gedik, Pablo Jarillo-Herrero, Di Xiao, and Mordechai Rothschild The workshop gathered the leading A lack of inversion symmetry coupled with the presence of time-reversal researchers in the field to present their symmetry endows 2D transition metal dichalcogenides with individually latest work and to participate in honest and addressable valleys in momentum space at the K and K′ points in the first open discussion about the opportunities Brillouin zone. This valley addressability opens up the possibility of using the and challenges of developing applications of valleytronic technology. Three interactive momentum state of electrons, holes, or excitons as a completely new para- working sessions were held, which tackled digm in information processing. The opportunities and challenges associated difficult topics ranging from potential with manipulation of the valley degree of freedom for practical quantum and applications in information processing and classical information processing applications were analyzed during the 2017 optoelectronic devices to identifying the Workshop on Valleytronic Materials, Architectures, and Devices; this Review most important unresolved physics ques- presents the major findings of the workshop. tions. The primary product of the work- shop is this article that aims to inform the reader on potential benefits of valleytronic 1. Background devices, on the state-of-the-art in valleytronics research, and on the challenges to be overcome. We are hopeful this document The Valleytronics Materials, Architectures, and Devices Work- will also serve to focus future government-sponsored research shop, sponsored by the MIT Lincoln Laboratory Technology programs in fruitful directions. -

Electronic Structure Theory for Periodic Systems: the Concepts

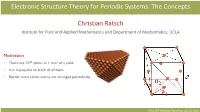

Electronic Structure Theory for Periodic Systems: The Concepts Christian Ratsch Institute for Pure and Applied Mathematics and Department of Mathematics, UCLA Motivation • There are 1020 atoms in 1 mm3 of a solid. • It is impossible to track all of them. • But for most solids, atoms are arranged periodically Christian Ratsch, UCLA IPAM, DFT Hands-On Workshop, July 22, 2014 Outline Part 1 Part 2 • Periodicity in real space • The supercell approach • Primitive cell and Wigner Seitz cell • Application: Adatom on a surface (to calculate for example a diffusion barrier) • 14 Bravais lattices • Surfaces and Surface Energies • Periodicity in reciprocal space • Surface energies for systems with multiple • Brillouin zone, and irreducible Brillouin zone species, and variations of stoichiometry • Bandstructures • Ab-Initio thermodynamics • Bloch theorem • K-points Christian Ratsch, UCLA IPAM, DFT Hands-On Workshop, July 22, 2014 Primitive Cell and Wigner Seitz Cell a2 a1 a2 a1 primitive cell Non-primitive cell Wigner-Seitz cell = + 푹 푁1풂1 푁2풂2 Christian Ratsch, UCLA IPAM, DFT Hands-On Workshop, July 22, 2014 Primitive Cell and Wigner Seitz Cell Face-center cubic (fcc) in 3D: Primitive cell Wigner-Seitz cell = + + 1 1 2 2 3 3 Christian푹 Ratsch, UCLA푁 풂 푁 풂 푁 풂 IPAM, DFT Hands-On Workshop, July 22, 2014 How Do Atoms arrange in Solid Atoms with no valence electrons: Atoms with s valence electrons: Atoms with s and p valence electrons: (noble elements) (alkalis) (group IV elements) • all electronic shells are filled • s orbitals are spherically • Linear combination between s and p • weak interactions symmetric orbitals form directional orbitals, • arrangement is closest packing • no particular preference for which lead to directional, covalent of hard shells, i.e., fcc or hcp orientation bonds.