Island Language Policy and Regional Identity East of Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 22 - Comoros

Marubeni Research Institute 2016/09/02 Sub -Saharan Report Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the focal regions of Global Challenge 2015. These reports are by Mr. Kenshi Tsunemine, an expatriate employee working in Johannesburg with a view across the region. Vol. 22 - Comoros June 10, 2016 It was well known that Marilyn Monroe wore Chanel No. 5 perfume when she went to bed. Did you know that Chanel No. 5’s essence (essential oils) comes from the flower called ylang-ylang, which is found in the African country of Comoros? Comoros is also where the so-called “living fossils”, a rare pre-historic species of fish called coelacanths, discovered in 1938 in South Africa after having thought to be extinct, are mostly found. So this time I would like to introduce the country of Comoros, fascinating like Marilyn Monroe and a little mysterious like the coelacanths. Table 1: Comoros Country Information The Union of the Comoros is an archipelago island nation located off the coast of East Africa east of Mozambique and northwest from Madagascar. 4 main islands make up the Comoros archipelago, Grande Comore, Moheli, Anjouan and Mayotte, with Grande Comore, Moheli, and Anjouan forming the Union of Comoros and Mayotte falling under French jurisdiction as an ‘overseas department” or region. The population of the 3 islands making up the Union of the Comoros is about 800,000, while their total land area comes to 2,236 square kilometers, about the same land size as Tokyo, which makes it quite a small country. Nominal GDP is roughly $600 million, which is second from the bottom among the 45 sub-Saharan African countries, just above Sao Tome and Principe, and its population is the 5th lowest (note 1). -

The Outermost Regions European Lands in the World Mayotte

Açores Madeira Saint-Martin Canarias Guadeloupe THE OUTERMOST REGIONS Martinique Guyane Mayotte EUROPEAN LANDS IN THE WORLD La Réunion 235 000 inhabitants 374 km2 ● Situated in the northern Mozambique Channel in the Indian Ocean, 295 km from Madagascar, Mayotte is made of two main islands and islets, with 235 000 inhabitants ● The island has great natural and cultural assets which are an excellent base for developing tourism. Agricultu- Mamoudzou re, fisheries and aquaculture are traditional sectors, still MAYOTTE poorly structured. ● The region faces many challenges: a GDP reaching less than one third of the EU average; a high unemployment rate affecting in particular young people; a very young and mostly non-qualified population; a strong pres- sure of Illegal immigration. In addition, water resources are limited and basic infrastructures are still insufficient. WHAT WILL THE NEW STRATEGY BRING TO MAYOTTE? By encouraging the outermost regions to capitalise on their unique assets, the strategy will help them create new opportunities for their people, boost innovation in sectors like agriculture, fisheries or tourism, while deepening the cooperation with neighbour countries. For the Mayotte, the strategy could help support in particular: ✓ A solid blue economy sector, by encouraging the development of marine renewable energy, aquaculture and blue biotechnologies and local fisheries ✓ A more competitive agri-food sector with modernised production processes ✓ Enhanced mobility, employability and new skills for young people by financially -

Insular Autonomy: a Framework for Conflict Settlement? a Comparative Study of Corsica and the Åland Islands

INSULAR AUTONOMY: A FRAMEWORK FOR CONFLICT SETTLEMENT? A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF CORSICA AND THE ÅLAND ISLANDS Farimah DAFTARY ECMI Working Paper # 9 October 2000 EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR MINORITY ISSUES (ECMI) Schiffbruecke 12 (Kompagnietor Building) D-24939 Flensburg . Germany % +49-(0)461-14 14 9-0 fax +49-(0)461-14 14 9-19 e-mail: [email protected] internet: http://www.ecmi.de ECMI Working Paper # 9 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) Director: Marc Weller Issue Editors: Farimah Daftary and William McKinney © European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) 2000. ISSN 1435-9812 i The European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) is a non-partisan institution founded in 1996 by the Governments of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Federal Republic of Germany, and the German State of Schleswig-Holstein. ECMI was established in Flensburg, at the heart of the Danish-German border region, in order to draw from the encouraging example of peaceful coexistence between minorities and majorities achieved here. ECMI’s aim is to promote interdisciplinary research on issues related to minorities and majorities in a European perspective and to contribute to the improvement of inter-ethnic relations in those parts of Western and Eastern Europe where ethno- political tension and conflict prevail. ECMI Working Papers are written either by the staff of ECMI or by outside authors commissioned by the Centre. As ECMI does not propagate opinions of its own, the views expressed in any of its publications are the sole responsibility of the author concerned. ECMI Working Paper # 9 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) © ECMI 2000 CONTENTS I. -

The EU and Its Overseas Entities Joining Forces on Biodiversity and Climate Change

BEST The EU and its overseas entities Joining forces on biodiversity and climate change Photo 1 4.2” x 10.31” Position x: 8.74”, y: .18” Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Azores Madeira French Guadeloupe Canary Guiana Martinique islands Reunion Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Anguilla British Virgin Is. Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores Aruba Wallis Bonaire French & Futuna Caraçao Ascension Polynesia Mayotte BIOT (British Indian Ocean Ter.) St Helena Scattered New Islands Caledonia Pitcairn Tristan da Cunha Amsterdam St-Paul South Georgia Crozet Islands TAAF (Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises) Iles Sandwich Falklands Kerguelen (Islas Malvinas) BAT (British Antarctic Territory) Adélie Land Overseas Countries and Territories (OCTs) Anguilla The EU overseas dimension British Virgin Is. Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique Aruba French Guiana Wallis Bonaire French & Futuna Caraçao Ascension Polynesia Mayotte BIOT (British Indian Ocean Ter.) St Helena Reunion Scattered New Islands Caledonia Pitcairn Tristan da Cunha Amsterdam St-Paul South Georgia Crozet Islands TAAF (Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises) Iles Sandwich Falklands Kerguelen (Islas Malvinas) BAT (British Antarctic Territory) Adélie Land ORs OCTs Anguilla The EU overseas dimension British Virgin Is. A major potential for cooperation on climate change and biodiversity Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. -

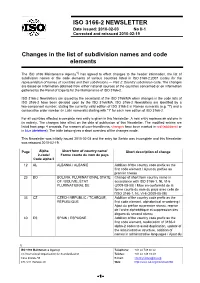

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

The Outermost Regions European Lands in the World

THE OUTERMOST REGIONS EUROPEAN LANDS IN THE WORLD Açores Madeira Saint-Martin Canarias Guadeloupe Martinique Guyane Mayotte La Réunion Regional and Urban Policy Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Communication Agnès Monfret Avenue de Beaulieu 1 – 1160 Bruxelles Email: [email protected] Internet: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/index_en.htm This publication is printed in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese and is available at: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/activity/outermost/index_en.cfm © Copyrights: Cover: iStockphoto – Shutterstock; page 6: iStockphoto; page 8: EC; page 9: EC; page 11: iStockphoto; EC; page 13: EC; page 14: EC; page 15: EC; page 17: iStockphoto; page 18: EC; page 19: EC; page 21: iStockphoto; page 22: EC; page 23: EC; page 27: iStockphoto; page 28: EC; page 29: EC; page 30: EC; page 32: iStockphoto; page 33: iStockphoto; page 34: iStockphoto; page 35: EC; page 37: iStockphoto; page 38: EC; page 39: EC; page 41: iStockphoto; page 42: EC; page 43: EC; page 45: iStockphoto; page 46: EC; page 47: EC. Source of statistics: Eurostat 2014 The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the European Commission. More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. -

Recommendation 3 ISO Country Code for Representation of Names of Countries

Recommendation 3 ISO COUNTRY CODE for Representation of Names of Countries At its first session, held in January 1972, the Group of The Working Party on Facilitation of International Trade Experts on Automatic Data Processing and Coding de- Procedures, cided to include in its programme of work the following Being aware of the need of an internationally agreed code task: system to represent names of countries, “To define requirements for country codes for use in Considering the International Standard ISO 3166 “Codes international trade, to be forwarded to ISO and to be for the representation of names of countries” as a suitable pursued in co-operation with it”. basis for application in international trade, It was entrusted to the secretariat to pursue this task. Recommends that the two-letter alphabetic code referred to in the International Standard ISO 3166 as “ISO AL- At a Meeting of the relevant ISO body, Working Group 2 PHA-2 Country Code”, should be used for representing of Technical Committee 46 “Documentation” in April the names of countries for purposes of International Trade 1972, it was agreed to set up a Co-ordination Committee whenever there is a need for a coded alphabetical desig- with the task to prepare proposals regarding a list of nation; entities, candidate numerical and alphabetical codes and maintenance arrangements. This Committee was com- Invites the secretariat to inform the appropriate ISO body posed of one representative each from ISO and ITU and responsible for the maintenance of ISO 3166 of any of the UNCTAD Trade Facilitation Adviser. amendments which the Working Party may suggest. -

ESA-Listed Species in Manda Bay Lamu Archipelago Kenya

ESA-Listed Species in Manda Bay, Lamu Archipelago, Kenya Bibliography Hope Shinn, Librarian, NOAA Central Library Lisa Clarke, Librarian, NOAA Central Library NCRL subject guide 2020-17 https://doi.org/10.25923/5mxx-s153 December 2020 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research NOAA Central Library – Silver Spring, Maryland Table of Contents Background & Scope ............................................................................................................................ 3 Sources Reviewed ................................................................................................................................ 3 Section I: Corals ................................................................................................................................... 4 Section II: Fish ................................................................................................................................... 11 Section IV: Marine Mammals ............................................................................................................. 21 Section V: General ............................................................................................................................. 23 2 Background & Scope Manda Bay is located in the Lamu Archipelago, on the northern coast of Kenya. It is part of the Indian Ocean, home to diverse marine species. This bibliography focuses on literature regarding the presence of Endangered Species Act (ESA) -

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Forest Health & Biosecurity Working Papers Case Studies on the Status of Invasive Woody Plant Species in the Western Indian Ocean 2. The Comoros Archipelago (Union of the Comoros and Mayotte) By P. Vos Forestry Section, Ministry of Environment & Natural Resources, Seychelles May 2004 Forest Resources Development Service Working Paper FBS/4-2E Forest Resources Division FAO, Rome, Italy Disclaimer The FAO Forestry Department Working Papers report on issues and activities related to the conservation, sustainable use and management of forest resources. The purpose of these papers is to provide early information on on-going activities and programmes, and to stimulate discussion. This paper is one of a series of FAO documents on forestry-related health and biosecurity issues. The study was carried out from November 2002 to May 2003, and was financially supported by a special contribution of the FAO-Netherlands Partnership Programme on Agro-Biodiversity. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Quantitative information regarding the status of forest resources has been compiled according to sources, methodologies and protocols identified and selected by the author, for assessing the diversity and status of forest resources. For standardized methodologies and assessments on forest resources, please refer to FAO, 2003. State of the World’s Forests 2003; and to FAO, 2001. -

Cadre D'orientations Stratégiques 2018-2028

CADRE COS D’ORIENTATIONS STRATÉGIQUES 2018-2028 LA RÉUNION ET MAYOTTE SOMMAIRE I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 3 1. Un projet de santé deuxième génération ........................................................................................... 4 2. Un projet de santé pour deux territoires : La Réunion et Mayotte ...................................................... 5 3. Un projet de santé s’inscrivant dans le cadre de la stratégie de santé pour les Outre-Mer............... 5 4. Une politique co-construite avec les acteurs de santé de La Réunion et de Mayotte ....................... 6 II. DIAGNOSTIC DE LA SITUATION SANITAIRE A LA REUNION ET A MAYOTTE .................................................................................................................. 7 1. Diagnostic de la situation sanitaire à Mayotte .................................................................................... 7 2. Diagnostic de la situation sanitaire à La Réunion ............................................................................ 10 III. LE CADRE D’ORIENTATION STRATEGIQUE : 8 ENJEUX DE SANTE......... 12 1. L’amélioration de la santé de la femme, du couple et de l’enfant .................................................... 12 2. La préservation de la santé des jeunes ............................................................................................ 15 3. L’amélioration de la santé nutritionnelle .......................................................................................... -

Cash Transfers and Migration: Theory And

Working Paper Series Cash Transfers and Migration: Theory and Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial Jules Gazeaud Nova School of Business and Economics and NOVAFRICA Eric Mvukiyehe The World Bank Olivier Sterck University of Oxford ISSN 2183-0843 Working Paper No 2004 June 2020 NOVAFRICA Working Paper Series Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of NOVAFRICA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the center itself takes no institutional policy positions. NOVAFRICA is a knowledge center created by the Nova School of Business and Economics of the Nova University of Lisbon. Its mission is to produce distinctive expertise on business and economic development in Africa. A particular focus is on Portuguese-speaking Africa, i.e., Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and Sao Tome and Principe. The Center aims to produce knowledge and disseminate it through research projects, publications, policy advice, seminars, conferences and other events. NOVAFRICA Working Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. NOVAFRICA | Nova School of Business and Economics - Faculdade de Economia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa Campus de Carcavelos | Rua da Holanda, Nº 1, 2775-405 Carcavelos – Portugal | T: (+351) 213 801 673 | www.novafrica.org Cash Transfers and Migration: Theory and Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial* Jules Gazeaud † Eric Mvukiyehe ‡ Olivier Sterck § June 2020 Abstract Will the fast expansion of cash-based programming in developing countries increase international migration? Theoretically, cash transfers may foster interna- tional migration by relaxing liquidity, credit, and risk constraints. -

Gadmtools - ISO 3166-1 Alpha-3 [email protected] 2021-08-04

GADMTools - ISO 3166-1 alpha-3 [email protected] 2021-08-04 1 ID LEVEL_0 LEVEL_1 LEVEL_2 LEVEL_3 LEVEL_4 LEVEL_5 ABW Aruba AFG Afghanistan Province District AGO Angola Province Municpality|City Council Commune AIA Anguilla ALA Åland Municipality ALB Albania County District Bashkia AND Andorra Parish ANT ARE United Arab Emirates Emirate Municipal Region Municipality ARG Argentina Province Part ARM Armenia Province ASM American Samoa District County Village ATA Antarctica ATF French Southern Territories District ATG Antigua and Barbuda Dependency AUS Australia Territory Territory AUT Austria State Statutory City Municipality AZE Azerbaijan Region District BDI Burundi Province Commune Colline Sous Colline BEL Belgium Region Capital Region Arrondissement Commune BEN Benin Department Commune BFA Burkina Faso Region Province Department BGD Bangladesh Division Distict Upazilla Union BGR Bulgaria Province Municipality BHR Bahrain Governorate BHS Bahamas District 2 BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina District -?- Commune BLM Saint-Barthélemy BLR Belarus Region District BLZ Belize District BMU Bermuda Parish BOL Bolivia Department Province Municipality BRA Brazil State Municipality District BRB Barbados Parish BRN Brunei District Mukim BTN Bhutan District Village block BVT Bouvet Island BWA Botswana District Sub-district CAF Central African Republic Prefecture Sub-prefecture CAN Canada Province Census Division Town CCK Cocos Islands CHE Switzerland Canton District Municipality CHL Chile Region Province Municipality CHN China Province Prefecture