Green and Brown? Globalization and the Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

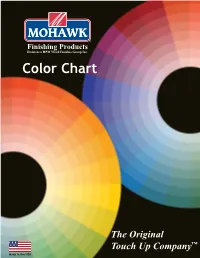

Color Chart.Pdf

® Finishing Products Division of RPM Wood Finishes Group Inc. Color Chart The Original Touch Up Company™ Made in the USA Color Chart ® Finishing Products Division of RPM Wood Finishes Group, Inc. Index Aerosols 1-5 Ultra® Classic Toner & Tone Finish Toner 1-3 Colored Lacquer Enamel 3-5 Shadow Toner 5 Touch-Up Markers/Pencils 5-15 Ultra® Mark Markers 5-9 3 in 1 Repair Stick 9 Pro-Mark® Markers 9-10 Quik-Tip™ Markers 10-11 Background Marker Touch-Up & Background Marker Glaze Hang-Up 11-13 Artisan Glaze Markers 13 Vinyl Marker Glaze Hang-Up 14 Brush Tip Graining Markers 14 Accent Pencils 15 Blend-Its 15 Fillers 15-29 Quick Fill® Burn-In Sticks 15-16 Edging/Low Heat Sticks 16 E-Z Flow™ Burn-In Sticks 16-17 PlaneStick® Burn-In Sticks 17-18 Fil-Stik® Putty Sticks 18-25 Hard Fill & Hard Fill Plus 25-27 PermaFill™ 27 Epoxy Putty Sticks 27-28 Patchal® Puttys 28-29 Knot Filler 29 Fil-O-Wood™ Wood Putty Tubes 29 Color Replacement 30-31 Blendal® Sticks 30 Sand Thru Sticks 30-31 Blendal® Powder Stains 31 Bronzing Powders 31 Dye Stains 32 Ultra® Penetrating & Architectural Ultra® Penetrating Stain 32 Dye Concentrate 32 Pigmented Stains 32-34 Wiping Wood™, Architectural Wiping Stain & Wiping Wood™ Stain Aerosols 32-33 Designer Series Stain, Designer Series Radiant Stain 33-34 Glazes 34 Finisher’s Glaze™ Glazing Stain & Aerosols 34 Break-A-Way™ Glaze & Aerosols 34 Leather Repair 35-37 E-Z Flow™ Leather Markers 35 Leather/Vinyl Markers 35 Leather/Vinyl Fil Sticks 35-36 Leather Repair Basecoat Aerosols 36 Leather Repair Toner Aerosols 36 Leather Repair Color Adjuster Aerosols 37 Touch Up Pigment 37 Leather Refinishing 37 Base Coat 37 NOTE: COLORS ARE APPROXIMATE REPRESENTATIONS OF ACTUAL COLORS USING MODERN PROCESS TECHNIQUES. -

Liquicolor Permanente Shades 07-10-12.Pdf

LIQUICOLOR PERMANENTE INTENSE INTENSE INTENSE INTENSE GOLD RED NEUTRAL (RN) INTENSE RED (RR) RED VIOLET (RV) RED VIOLET (RRV) BASE INTENSE NEUTRAL (NN) NEUTRAL (N) ASH (A) ASH (A) ASH (AA) ASH (AA) NEUTRAL(GN) GOLD (G) REDPELIRROJO NEUTRAL (RN) RED (R) INTENSEPELIRROJO RED (RR) REDPELIRROJO VIOLET (RV) REDPELIRROJO VIOLET (RRV) NEUTRAL INTENSO NEUTRAL CENIZO CENIZO CENIZO INTENSO CENIZO INTENSO DORADO NEUTRAL GOLDDORADO (G) PELIRROJONEUTRAL PELIRROJORED (R) PELIRROJOINTENSO PELIRROJOVIOLETA VIOLETAPELIRROJO INTENSO LEVEL/NIVEL DORADO NEUTRAL PELIRROJO INTENSO VIOLETA VIOLETA INTENSO 12 HIGH-LIFT BLONDE 12N/HL-N 12A/HL-V 12AA-B/HL-B 12AA-BV 12G / HL-G HIGH LIFT HIGH LIFT HIGH LIFT ULTRA HIGH LIFT ULTRA HIGH LIFT GOLDEN BLONDE NEUTRAL BLONDE COOL BLONDE COOL BLONDE BLUE COOL BLONDE BLUE VIOLET 10 LIGHTEST BLONDE RUBIO CLARÍSIMO 10N/12B1 10GN/12G2 OUR FIRST NN 10G / 12G LIGHTEST NEUTRAL BLONDE LIGHTEST GOLD LIQUID COLOR LIGHTEST GOLDEN BLONDE blondest beige NEUTRAL BLONDE blondest blonde blondest gold 9 VERY LIGHT BLONDE RUBIO MUY CLARO 9NN 9N/89N 9A/26D 9A-N/40D 9AA/20D 9AA-BV/30D VERY LIGHT RICH VERY LIGHT VERY LIGHT VERY LIGHT COOL VERY LIGHT ULTRA VERY LIGHT ULTRA COOL NEUTRAL BLONDE NEUTRAL BLONDE COOL BLONDE NEUTRAL BLONDE COOL BLONDE BLONDE BLUE VIOLET lightest neutral blonde winter wheat topaz arctic blonde flaxen blonde 8 LIGHT BLONDE RUBIO CLARO 8NN 8N/88N 8A / 28D 8GN/27G 8RN / 71RG 8R / 29R LIGHT RICH LIGHT LIGHT COOL BLONDE LIGHT GOLD NEUTRAL LIGHT RED NEUTRAL LIGHT RED BLONDE NEUTRAL BLONDE NEUTRAL BLONDE autumn mist BLONDE -

Color Communication Badges

Color Communication Badges GREEN YELLOW RED Color Communication Badges are a system which were first developed in Autistic spaces and conferences. They help people tell everyone who can see their badge about their communication preferences. A color communication badge is a name tag holder that can pin or clip onto clothing. In the name tag holder there are three cards: one green card that says “GREEN”, one yellow card that says “YELLOW”, and one red card that says “RED.” The card that is currently visible is the active card; the other two are hidden behind the first one, accessible to the person if they should need them. Showing a green badge means that the person is actively seeking communication; they have trouble initiating conversations, but want to be approached by people who are interested in talking. Showing a yellow badge means that the person only wants to talk to people they recognize, not by strangers or people they only know from the Internet. The badge-wearer might approach strangers to talk, and that is okay; the approached people are welcome to talk back to them in that case. But unless you have already met the person face-to-face, you should not approach them to talk. Showing a red badge means that the person probably does not want to talk to anyone, or only wants to talk to a few people. The person might approach others to talk, and that is okay; the approached people are welcome to talk back to them in that case. But unless you have been told already by the badge-wearer that you are on their “red list”, you should not approach them to talk. -

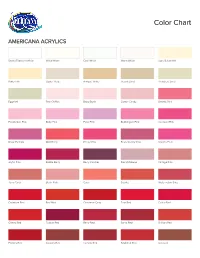

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

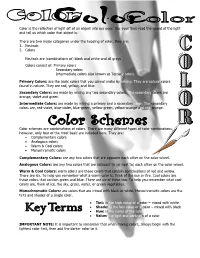

Color Schemes Are Combinations of Colors

Color is the reflection of light off of an object into our eyes. Our eyes then read the speed of the light and tell us which color that object is. There are two major categories under the heading of color, they are: 1. Neutrals 2. Colors Neutrals are (combinations of) black and white and all grays Colors consist of: Primary colors Secondary colors Intermediate colors also known as Tertiary colors Primary Colors: are the basic colors that you cannot make by mixing. They are natural colors found in nature. They are red, yellow, and blue. Secondary Colors: are made by mixing any two secondary colors. The secondary colors are orange, violet and green. Intermediate Colors: are made by mixing a primary and a secondary color. The secondary colors are, red-violet, blue-violet, blue-green, yellow-green, yellow-orange and red-orange. Color schemes are combinations of colors. There are many different types of color combinations, however, only four of the most basic are included here. They are: • Complementary colors • Analogous colors • Warm & Cool colors • Monochromatic colors Complementary Colors: are any two colors that are opposite each other on the color wheel. Analogous Colors: are any two colors that are adjacent to (or next to) each other on the color wheel. Warm & Cool Colors: warm colors are those colors that contain combinations of red and yellow. There are six. To help you remember what a warm color is, think of the sun or fire. Cool colors are those colors that contain green and blue. There are six of these too. -

Brown to Green Report

BROWN TO GREEN The G20 transition to a low-carbon economy | 2017 BROWN TO GREEN | 2017 AUTHORS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by Swati Agarwal (The Energy and Resources Institute), Bridget Boulle (Climate Bonds Initiative), Yann Briand (Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations), Jan Burck (Germanwatch), Ipek Gençsü (Overseas Development Institute), Sofia Gonzales-Zuñiga (NewClimate Institute), Markus Hagemann (NewClimate Institute), Niklas Höhne (NewClimate Institute), Jiang Kejun (Energy Research Institute China), Gerd Leipold (HUMBOLDT-VIADRINA Governance Platform), Karan Mangotra (The Energy and Resources Institute), Enrique Maurtua Konstantinidis (Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales), Andrew Marquard (Energy Research Center, University of Cape Town), Franziska Marten (Germanwatch), Mia Moisio (NewClimate Institute), Keno Riechers (NewClimate Institute), Hannah Schindler (HUMBOLDT- VIADRINA Governance Platform), Thomas Spencer (Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations), Fabby Tumiwa (Institute for Essential Service Reform), Thea Uhlich (Germanwatch), Jorge Villarreal (Iniciativa Climática de México), Charlene Watson (Overseas Development Institute), Shelagh Whitley (Overseas Development Institute), William Wills (CentroClima, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro). Responsibility for the report lies with the authors and does not necessarily represent the opinions of their organizations. We express our gratitude to the following contributors for their invaluable input -

Paint Pigments— Yellow

» TECHNICAL INFORMATION ON BUILDING MATERIALS TIBM - 32 FOR UfSE IN THE DESIGN OF LOW-COST HOUSING ***** THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE WASHINGTON, D. C. August 29, 1936 PAINT PIGMENTS— YELLOW, . BROWN, BLUE, GREEN, AND BRONZE This is urimarily^a digest of the sections of Bureau of Standards Circular No, o9> "Paint and Varnish", (November 17, 1917),'*' and Tech- nologic Paper No. 274, "Use of United States Government Suecif ication Paints and Faint Materials", (December 15, 1924), ^ Ly p, H. Walker and E. F. Hickson, dealing with general composition , characteristics, and uses of yellow, brown, blue, green, and bronze pigments. The following papers contain additional information relative to paint pigments, oil paints, and water paints: TIBM - 30 "Paint Pigments—White" TIBM - 31 "Paint Pigments—Black, Red, and Lakes" TIBM - 33 "Federal Specification . Paint Pigments and Mixing Formulas" TIM - 3U "Federal Specification Ready-Mixed Paints, Semi- paste Paints and Mixing Formulas’"' TIBM - 35 "Preparation of Paints from Paste and Dry Pigments" TIBM - 36 "Preparation of Paints from Semipaste Paints, Thinning Ready-Mixed Paints, and Preparation of Water Paints" TIBM - 43 "Aluminum Paints" Pigments are "the fine solid warticles used in the preparation of paint, and substantially insoluble in the vehicle, "3 In general, it may be ^Out of print. May be consulted in Government depositor}*- libraries. p Available from Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C. .(Price 10 cents). ^Qpioted from "Standard Definitions of Terms Relating to Paint 'Specifications", American Society for Testing Materials ( 1 93 3 ) ’ • • -• •• PP. 735-73 9 . 031736-C - 1 - assumed that pigments composed of very fine particles, having high re- fractive indices, provide the greatest covering power and opacity. -

Which Regions of the Electromagnetic Spectrum Do Plants Use to Drive Photosynthesis?

Which regions of the electromagnetic spectrum do plants use to drive photosynthesis? Green Light: The Forgotten Region of the Spectrum. In the past, plant physiologists used green light as a safe light during experiments that required darkness. It was assumed that plants reflected most of the green light and that it did not induce photosynthesis. Yes, plants do reflect green light but human vision sensitivity peaks in the green region at about 560 nm, which allows us to preferentially see green. Plants do not reflect all of the green light that falls on them but they reflect enough for us to detect it. Read on to find out what the role of green light is in photosynthesis. The electromagnetic spectrum: Light Visible light ranges from low blue to far-red light and is described as the wavelengths between 380 nm and 750 nm, although this varies between individuals. The region between 400 nm and 700 nm is what plants use to drive photosynthesis and is typically referred to as Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR). There is an inverse relationship between wavelength and quantum energy, the higher the wavelength the lower quantum energy and vice versa. Plants use wavelengths outside of PAR for the phenomenon known as photomorphogenesis, which is light regulated changes in development, morphology, biochemistry and cell structure and function. The effects of different wavelengths on plant function and form are complex and are proving to be an interesting area of study for many plant scientists. The use of specific and adjustable LEDs allows us to tease apart the roles of specific areas of the spectrum in photosynthesis. -

R-E-D, Red, R-E-D, Red, I Can Spell Red, I Can Spell Red

RED Tune: “Are You Sleeping?” R-e-d, red, R-e-d, red, I can spell red, I can spell red. are red, are red, too. R-e-d, r-e-d. YELLOW Tune: “If You’re Happy and You Know It” Y-e-l-l-o-w spells yellow. Y-e-l-l-o-w spells yellow. Like the early morning , When the day has just begun. Y-e-l-l-o-w spells yellow. and baby are yellow. and scrambled are yellow. I like the that’s yellow, He is such a happy fellow! Y-e-l-l-o-w spells yellow. BLUE Tune: “The Farmer in the Dell” B-l-u-e spells blue. B-l-u-e spells blue. Hi-ho did you know B-l-u-e spells blue? The big is blue. The is, too. Hi-ho did you know B-l-u-e spells blue? GREEN Tune: “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” G-r-e-e-n, G-r-e-e-n. I know how to spell green, G-r-e-e-n. are green And , too. I know how to spell green, G-r-e-e-n. ORANGE Tune: “The Wheels on the Bus” O-r-a-n-g-e, O-r-a-n-g-e, O-r-a-n-g-e, Orange is what that spells. are always orange. are always orange. are always orange. O-r-a-n-g---------e! BROWN Tune: “Bingo” There is a color we all know, Can you guess what it is? B-r-o-w-n, b-r-o-w-n, b-r-o-w-n, That’s how you spell brown. -

R Color Cheatsheet

R Color Palettes R color cheatsheet This is for all of you who don’t know anything Finding a good color scheme for presenting data about color theory, and don’t care but want can be challenging. This color cheatsheet will help! some nice colors on your map or figure….NOW! R uses hexadecimal to represent colors TIP: When it comes to selecting a color palette, Hexadecimal is a base-16 number system used to describe DO NOT try to handpick individual colors! You will color. Red, green, and blue are each represented by two characters (#rrggbb). Each character has 16 possible waste a lot of time and the result will probably not symbols: 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,A,B,C,D,E,F: be all that great. R has some good packages for color palettes. Here are some of the options “00” can be interpreted as 0.0 and “FF” as 1.0 Packages: grDevices and i.e., red= #FF0000 , black=#000000, white = #FFFFFF grDevices colorRamps palettes Two additional characters (with the same scale) can be grDevices comes with the base cm.colors added to the end to describe transparency (#rrggbbaa) installation and colorRamps topo.colors terrain.colors R has 657 built in color names Example: must be installed. Each palette’s heat.colors To see a list of names: function has an argument for rainbow colors() peachpuff4 the number of colors and see P. 4 for These colors are displayed on P. 3. transparency (alpha): options R translates various color models to hex, e.g.: heat.colors(4, alpha=1) • RGB (red, green, blue): The default intensity scale in R > #FF0000FF" "#FF8000FF" "#FFFF00FF" "#FFFF80FF“ ranges from 0-1; but another commonly used scale is 0- 255. -

Watercolor Substitution Cheat Sheet * = Lindsay Recommended Color

Watercolor Substitution Cheat Sheet * = Lindsay Recommended color *Phthalo Blue (Strong cool-green leaning-blue) Prussian Blue (also look for that pigment) AKA Pthalo blue GS Cyan Blue or green shade. Cerulean Blue (if it looks dark: Mission Gold) Helio Cerulean **This colors is great for mixing green when Winsor Blue (Winsor & Newton) paired with a cool yellow. Intense Blue (Winsor & Newton/Cotman) Azure (Yarka/White Nights) Turquoise Indigo (deep cool blue grey) Indanthrone Blue Payne's Grey+Prussian Blue *Ultramarine Blue (warm, purple bias red) Colbalt Blue Pthalo blue Red Shade (not my fave substitute) **This color is good for mixing violet with a cool Poland Blue red or gray with burnt sienna. ***This color granulates for textured washes. Cerulean Blue (Less intense cool blue) Manganese Blue Phthalo blue + white Cinerous Blue (Sennelier) *Quinacridone Rose (Cool red with violet Alizarian Crimson undertones) Carmine **This color makes lovely purples and mauve Crimson lake with blues. Rose Madder (weaker than AZ) *Cadmium Red or Cadmium red light Vermilion (Warm red with orange undertones) Scarlet Napthol Red **This color makes beautiful oranges when mixed Bright Red/ Brilliant Red with warm yellows. Pyrrole Red Permanent Rose Magenta *Cadmium Yellow (warm yellow) Gamboge Cadmium yellow medium/Cadmium yellow deep Indian Yellow Permanent yellow deep **This color makes beautiful oranges when mixed with warm reds or peach with cool reds *Hansa Yellow Light (cool yellow) Lemon Yellow (cool yellow) Cadmium yellow light, pale or Cadmium