A Feminist Review of John Dramani Mahama's My First Coup D'etat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rawlings' Factor in Ghana's Politics

al Science tic & li P Brenya et al., J Pol Sci Pub Aff 2015, S1 o u P b f l i o c DOI: 10.4172/2332-0761.S1-004 l Journal of Political Sciences & A a f n f r a u i r o s J ISSN: 2332-0761 Public Affairs Research Article Open Access The Rawlings’ Factor in Ghana’s Politics: An Appraisal of Some Secondary and Primary Data Brenya E, Adu-Gyamfi S*, Afful I, Darkwa B, Richmond MB, Korkor SO, Boakye ES and Turkson GK Department of History and Political Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana Abstract Global concern for good leadership and democracy necessitates an examination of how good governance impacts the growth and development of a country. Since independence, Ghana has made giant strides towards good governance and democracy. Jerry John Rawlings has ruled the country for significant period of the three decades. Rawlings emerged on the political scene in 1979 through coup d’état as a junior officer who led the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) and eventually consolidated his rule as a legitimate democratically elected President of Ghana under the fourth republican constitution in 1992. Therefore, Ghana’s political history cannot be complete without a thorough examination of the role of the Rawlings in the developmental/democratic process of Ghana. However, there are different contentions about the impact of Rawlings on the developmental and democratic process of Ghana. This study examines the impacts of Rawlings’ administration on the politics of Ghana using both qualitative and quantitative analytical tools. -

“The World Bank Did It

CDDRL Number 82 WORKING PAPERS May 2008 “The World Bank Made Me Do It?” International Factors and Ghana’s Transition to Democracy Antoinette Handley University of Toronto Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Additional working papers appear on CDDRL’s website: http://cddrl.stanford.edu. Paper prepared for CDDRL Workshop on External Influences on Democratic Transitions. Stanford University, October 25-26, 2007. REVISED for CDDRL’s Authors Workshop “Evaluating International Influences on Democratic Development” on March 5-6, 2009. Center on Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Stanford University Encina Hall Stanford, CA 94305 Phone: 650-724-7197 Fax: 650-724-2996 http://cddrl.stanford.edu/ About the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL) CDDRL was founded by a generous grant from the Bill and Flora Hewlett Foundation in October in 2002 as part of the Stanford Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. The Center supports analytic studies, policy relevant research, training and outreach activities to assist developing countries in the design and implementation of policies to foster growth, democracy, and the rule of law. “The World Bank made me do it”? Domestic and International factors in Ghana’s transition to democracy∗ Antoinette Handley Department of Political Science University of Toronto [email protected] Paper prepared for CDDRL, Stanford University, CA March 5-6, 2009 DRAFT: Comments and critiques welcome. Please do not cite without permission of the author. ∗ This paper is based on a report commissioned by CDDRL at Stanford University for a comparative project on the international factors shaping transitions to democracy worldwide. -

Imaging a President: Rawlings in the Ghanaian Chronicle

IMAGING A PRESIDENT: RAWLINGS IN THE GHANAIAN CHRONICLE Kweku Osam* Abstract The post-independence political hist01y of Ghana is replete with failed civilian and military governments. At the close of the 1970s and the beginning of the I 980s, a young Air Force Officer, Flt. Lt. Jerry John Rawlings, burst onto the political scene through a coup. After a return to civilian rule in I 99 2, with him as Head of State, he was to finally step down in 2000. For a greater part of his rule, press freedom was curtailed. But with the advent ofcivilian rule backed by a Constitution that guarantees press freedom, the country experienced a phenomenal increase in privately-owned media. One of these is The Ghanaian Chronicle, the most popular private newspaper in the last years of Rawlings' time in office. This study, under the influence of Critical Discourse Analysis,· examines "Letters to the Editor" published in The Ghanaian Chronicle that focused on Rawlings. Through manipulating various discourse structures, writers of these letters project an anti Rwalings ideology as a means of resisting what they see as political dominance reflected in Rawlings rule. 1. Introduction Critical studies of media discourse have revealed that media texts are not free from ideological biases. Throughout the world, it has been observed that various discourse types in the media, for example, editorials, opinion, and letters provide conduits for the expression of ideologies. In Ghana, many of the studies carried out on the contents of the media have tended to be done through the traditional approach of content analysis. -

Commemorating an African Queen Ghanaian Nationalism, the African Diaspora, and the Public Memory of Nana Yaa Asantewaa, 1952–2009

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Faculty Publications Department of History 2014 Commemorating an African Queen Ghanaian Nationalism, the African Diaspora, and the Public Memory of Nana Yaa Asantewaa, 1952–2009 Harcourt Fuller Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_facpub Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Fuller, H. “Commemorating an African Queen: Ghanaian Nationalism, the African Diaspora, and the Public Memory of Nana Yaa Asantewaa, 1952 – 2009.” African Arts 47.4 (Winter 2014): 58-71. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commemorating an African Queen Ghanaian Nationalism, the African Diaspora, and the Public Memory of Nana Yaa Asantewaa, 1952–2009 Harcourt Fuller All photos by the author except where otherwise noted he years 2000–2001 marked the centennial of deeds of Yaa Asantewaa. The minister encouraged the nation to the Anglo-Asante War (otherwise known as the commemorate Yaa Asantewaa’s heroism, demonstrated through War of the Golden Stool) of 1900–1901. This bat- her self-sacrifice in defending the Golden Stool in 1900–1901. tle was led by Nana Yaa Asantewaa (ca. 1832– He also recommended that a history book be published on her 1923), the Queen Mother from the Asona royal life, personality, and the War of Resistance specifically. His sug- family of the Asante paramount state of Ejisu, gestions resulted in the 2002 publication of Yaa Asantewaa: An who took up arms to prevent the British from capturing the African Queen Who Led an Army to Fight the British by Asirifi Tsacred Golden Stool.1 This milestone produced several publica- Danquah, a veteran Ghanaian journalist. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah's Independence Speech

New Media and Mass Communication www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3267 (Paper) ISSN 2224-3275 (Online) Vol.43, 2015 A Rhetorical Analysis of Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah’s Independence Speech Abena Abokoma Asemanyi Anita Brenda Alofah Department of Communication and Media Studies, University of Education, Winneba, P.O. Box 25, Winneba, Central Region, Ghana Abstract The study examines the role of rhetoric in the famous Independence Speech given by the first president of the Republic of Ghana, Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah at Old Polo Grounds, Accra, Ghana on 6 th March, 1957 when Ghana won independence from the British rule. Through a rhetorical analysis and specifically using the cannons of rhetoric and the means of persuasion, the study finds that; first, the speech adopts the elements of rhetoric to inform, encourage and persuade its audiences.; second, the speech is endowed with the richness that the five canons of rhetoric afford. The study reveals that the powerful diction and expressions embedded in the speech follow a rather careful arrangement meant to achieve the objective of rhetoric; third, the speaker adopted the three means of persuasion, namely: ethos, pathos and logos, to drive home the objective of his argument. The findings agree with Ghanaian Agenda’s assertion of the speech as one of the greatest ever written and delivered in Ghanaian geo-politics and rhetorical history. The study concludes that the 1957 Independence Speech by Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah owes its world-wide garnered attention to the power of rhetoric, owing to the fact that it affords the speech the craft of carefully laid out rhetorical constructions and principles and hence making the speech a powerful work of rhetoric. -

History of Ghana Advisory Board

THE HISTORY OF GHANA ADVISORY BOARD John T. Alexander Professor of History and Russian and European Studies, University of Kansas Robert A. Divine George W. Littlefield Professor in American History Emeritus, University of Texas at Austin John V. Lombardi Professor of History, University of Florida THE HISTORY OF GHANA Roger S. Gocking The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations Frank W. Thackeray and John E. Findiing, Series Editors Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cocking, Roger. The history of Ghana / Roger S. Gocking. p. cm. — (The Greenwood histories of the modern nations, ISSN 1096-2905) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-313-31894-8 (alk. paper) 1. Ghana—History. I. Title. II. Series. DT510.5.G63 2005 966.7—dc22 2004028236 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2005 by Roger S. Gocking All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2004028236 ISBN: 0-313-31894-8 ISSN: 1096-2905 First published in 2005 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48-1984). 10 987654321 Contents Series Foreword vii Frank W. Thackeray and John -

ECFG-Ghana-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Ghana Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Ghana, focusing on unique cultural features of Ghanaian society and is designed to complement other pre- deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

Primary 4 History of Ghana Facilitator's Guide

HISTORY OF GHANA for Basic Schools FACILITATOR’S GUIDE 4 • Bruno Osafo • Peter Boakye Published by WINMAT PUBLISHERS LTD No. 27 Ashiokai Street P.O. Box 8077 Accra North Ghana Tel.:+233 552 570 422 / +233 302 978 784 www.winmatpublishers.com [email protected] ISBN: 978-9988-0-4842-6 Text © Bruno Osafo, Peter Boakye 2020 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. Typeset by: Daniel Akrong Cover design by: Daniel Akrong Edited by: Akosua Dzifa Eghan and Eyra Doe The publishers have made every effort to trace all copyright holders but if they have inadvertently overlooked any, they will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity. TABLE OF CONTENTS STRAND 1: History as a Subject 1 Sub-Strand 1: Why and How we Study History 1 STRAND 2: My Country Ghana 9 Sub-Strand 1: The People of Ghana 9 Sub-Strand 4: Major Historical Locations 15 Sub-Strand 5: Some Selected Individuals 21 STRAND 3: Europeans In Ghana 29 Sub-Strand 3: Missionary Activities 29 STRAND 4: Colonisation and Developments under Coloinal rule in Ghana 40 Sub-Strand 1: Establishing British Rule in Ghana 40 STRAND 6: Independent Ghana 49 Sub-Strand 1: The Republics 49 Introduction This Facilitator’s Guide has been carefully written to help Facilitator’s meet the expectations of the History of Ghana Curriculum developed by the Ministry of Education. -

Religion, Education and Development in Ghana

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.3, No.12, pp.6-18, December 2015 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) RELIGION, EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT IN GHANA: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE John Kwaku Opoku, Eric Manu and Frimpong Wiafe Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Faculty of Social Sciences, Department of Religious Studies Kumasi-Ghana ABSTRACT: ‘Religion’ and ‘Education’ are inseparable aspects in every human society where they are found. Education has most often been considered as the backbone of development. Similarly, many development theorists have expounded the contributions of religion toward development. The responsibility that religions share in human societies are realised in different aspects of national life. Of particular concern is religions’ role in education toward national development. This work is discussed from the dimensions of the contributions of Christianity and Islam in education in Ghana. Generally, education is understood to mean to train or mould. In this study, it implies the art of learning, literacy and the process of acquiring knowledge. In the quest to advance the livelihood of members of society through education, it has become important to expatiate the task of religion in the development of education. This is to help stamp out the reluctance to consider the influence of religion in sustainable and authentic human and national development. This paper is primarily purposed to outline the contributions of religion and education to national development in Ghana. The quest for an all-inclusive development model of Ghana and other developing nations, therefore, calls for an insight into the role and responsibilities of religion toward education. -

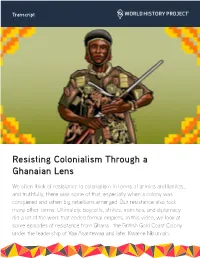

Resisting Colonialism Through a Ghanaian Lens

Transcript Resisting Colonialism Through a Ghanaian Lens We often think of resistance to colonialism in terms of armies and battles… and truthfully, there was some of that, especially when a colony was conquered and when big rebellions emerged. But resistance also took many other forms. Ultimately, boycotts, strikes, marches, and diplomacy did a lot of the work that ended formal empires. In this video, we look at some episodes of resistance from Ghana—the British Gold Coast Colony— under the leadership of Yaa Asantewaa and later Kwame Nkrumah. Transcript Resisting Colonialism Through a Ghanaian Lens Timing and description Text 00:01 My name is Trevor Getz and I’m a professor of African history at San Francisco State University. And I’m here in Ghana, in West Africa, a place that, like most Trevor Getz, PhD, San of the rest of the continent, was made up of independent states and small, self- Francisco State University ruling communities until the 1870s. And then, in that decade, Europeans began to carve out colonies and create vast empires across the continent. By 1916, almost Animated map of the all of the continent had been conquered other than Ethiopia and tiny Liberia. But African continent shows from the very beginning, Africans resisted, and by the 1960s, colonialism was in the location of Ghana; retreat across the continent. This was nowhere more true than in Ghana, where we see the continent independence was won in 1957—the first sub-Saharan African state to become transform from a continent independent. of independent states to an almost entirely colonized continent 00:58 How did this happen? Well, the great Ghanaian historian Adu Boahen says, “Independence was not given on a silver platter, but won by blood.” In other words, African resistance led to African independence. -

Kwame Nkrumah & Julius Nyerere

Sam Swoyer Honors Capstone Professor Steven Taylor Kwame Nkrumah & Julius Nyerere: Independence, Leadership, & Legacy I. Introduction One of the more compelling movements of the second half of the twentieth century was the rise of the African independence movements. The first fifty years after 1880 had seen a great scramble by the European colonial powers for territory in Africa, followed by readjustments in colonial possessions in the aftermath of both World War I and World War II. Through this period of colonialism and subjugation, only the countries of Liberia, founded with the support of the United States, and Ethiopia, which 1 overcame a short period of subjugation by Mussolini’s Italy during the Second World War, remained independent. The entirety of the rest of the continent was subjected to colonization efforts by the likes of Great Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, and Belgium. After the First World War, many of Germany’s colonial possessions were entrusted to Allied countries as League of Nations mandates in accordance with the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I. After World War II, the mandates became United Nations trusteeships. One of, if not the, most influential colonial power during this time was Great Britain. During its peak, the country could claim that the “sun never set on the British Empire,” and the Empire’s colonial holdings in Africa were a large part of its possessions. At one point or another, the British Empire exerted control over the colonies of Gambia, Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast, Nigeria, Southern Cameroon, Libya, Egypt, the Sudan, Eritrea, Somalia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, Northern Rhodesia, Rhodesia, Nyasaland, Swaziland, and South Africa. -

Military Coups in Ghana, 1969-1985; a By-Product of Global Economic Injustices?

MILITARY COUPS IN GHANA, 1969-1985; A BY-PRODUCT OF GLOBAL ECONOMIC INJUSTICES? AUTHOR KWAKU GYENING OWUSU MSc INTERNATIONAL AND EUROPEAN RELATIONS SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT AND ECONOMICS LINKÖPINGS UNIVERSITET-SWEDEN DATE 03 JUNE 2008 LIU-IEI-FIL-A--08/00332--SE SUPERVISED BY ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR DR PER JANSSON 1 AKNOWLEDGEMENT I thank God Almighty for guiding and protecting me through out my whole study and stay in Sweden and also giving me the strength to complete my master’s education. I also thank my supervisor Associate Professor Dr. Per Jansson who has been of so much help in writing of my thesis and also helping me to understand the proper use of theories. His guidance and efforts have brought me this far to complete this thesis and I wonder how I would have achieved this without his enormous co-operation. I also thank all the staff of the department, the lecturers who lectured me and Kerstin Karlsson for her never ending support in her administrative work during my study at the department. Last of all I thank my parents, my fiancée, my brothers and my newly born baby Adriel who were always supporting me morally, spiritually and financially to bring me this far. God Bless you all……… 2 Table of Contents 3 Abstract 4 Abbreviations 4 Chapter 1: Introduction 6 1:1 Background and Brief History 6 1:2 Aims and Research Questions 8 1:3 Methodology 9 1:3:1 Research Strategy 9 1:3:2 Research Design 10 1:3:3 Collections of Information and Data 11 1:4 Theoretical and Empirical Literatures 11 1:4:1 Theoretical Literature 11 1:4:2 Empirical Literatures