Teaching the Ethical Values Governing Mediator Impartiality Using Short Lectures, Buzz Group Discussions, Video Clips, a Defini

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Trap Pilates POPUP

TRAP PILATES …Everything is Love "The Carters" June 2018 POP UP… Shhh I Do Trap Pilates DeJa- Vu INTR0 Beyonce & JayZ SUMMER Roll Ups….( Pelvic Curl | HipLifts) (Shoulder Bridge | Leg Lifts) The Carters APESHIT On Back..arms above head...lift up lifting right leg up lower slowly then lift left leg..alternating SLOWLY The Carters Into (ROWING) Fingers laced together going Side to Side then arms to ceiling REPEAT BOSS Scissors into Circles The Carters 713 Starting w/ Plank on hands…knee taps then lift booty & then Inhale all the way forward to your tippy toes The Carters exhale booty toward the ceiling….then keep booty up…TWERK shake booty Drunk in Love Lit & Wasted Beyonce & Jayz Crazy in Love Hands behind head...Lift Shoulders extend legs out and back into crunches then to the ceiling into Beyonce & JayZ crunches BLACK EFFECT Double Leg lifts The Carters FRIENDS Plank dips The Carters Top Off U Dance Jay Z, Beyonce, Future, DJ Khalid Upgrade You Squats....($$$MOVES) Beyonce & Jay-Z Legs apart feet plie out back straight squat down and up then pulses then lift and hold then lower lift heel one at a time then into frogy jumps keeping legs wide and touch floor with hands and jump back to top NICE DJ Bow into Legs Plie out Heel Raises The Carters 03'Bonnie & Clyde On all 4 toes (Push Up Prep Position) into Shoulder U Dance Beyonce & JayZ Repeat HEARD ABOUT US On Back then bend knees feet into mat...Hip lifts keeping booty off the mat..into doubles The Cartersl then walk feet ..out out in in.. -

Part Ii : Methodological Developments

THESE DE DOCTORAT Spécialité écologie marine Ecole doctorale des sciences de l’environnement d’Île de France Présentée par Karine Heerah Pour obtenir le grade de Docteur de l’Université Pierre et Marie Curie et de l’Université de Tasmanie ECOLOGIE EN MER DES PHOQUES DE WEDDELL DE L’ANTARCTIQUE DE L’EST EN RELATION AVEC LES PARAMETRES PHYSIQUES DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT AT SEA ECOLOGY OF WEDDELL SEALS IN EAST ANTARCTICA IN RELATION WITH ENVIRONMENTAL PHYSICAL PARAMETERS Thèse soutenue le 9 octobre 2014 Devant le jury composé : Philippe Koubbi Prof. UPMC Président du jury Jennifer Burns Prof. UAA Rapporteur Rory Wilson Prof. Swansea University Rapporteur Marie-Noëlle Houssais DR CNRS Examinatrice Charles-André Bost DR CNRS Examinateur Jean-Benoît Charrassin Prof. MNHN Directeur de thèse Mark Hindell Prof. UTAS Directeur de thèse Christophe Guinet DR CNRS Co-directeur de thèse 1 A mes merveilleux parents, Mon frère et mes sœurs ainsi qu’Henri, Janet, Et Michèle, 3 « Pendant que je regarde vers le large, le soleil se couche insensiblement, les teintes bleues si variées et si douces des icebergs sont devenues plus crues, bientôt le bleu foncé des crevasses et des fentes persiste seul, puis graduellement succède avec une douceur exquise une teinte maintenant rose et c’est tellement beau, qu’en me demandant si je rêve, je voudrais rêver toujours… …On dirait les ruines d’une énorme et magnifique ville tout entière du marbre le plus pur, dominée par un nombre infini d’amphithéâtres et de temples édifiés par de puissants et divins architectes. Le ciel devient une coquille de nacre où s’irisent, en se confondant sans se heurter, toutes les couleurs de la nature… Sans que je m’en aperçoive, la nuit est venue et lorsque Pléneau, en me touchant l’épaule, me réveille en sursaut de cette contemplation, j’essuie pertinemment une larme, non de chagrin, mais de belle et puissante émotion. -

Listen up LISTEN up Album of the Week, Notables 6D

USA TODAY 8D LIFE TUESDAY, MARCH 18, 2014 More Listen Up LISTEN UP Album of the week, notables 6D SONG OF THE WEEK THE PLAYLIST USA TODAY music critic Brian Mansfield highlights 10 intriguing tracks discovered during the week’s listening. ‘Fallinlove2nite,’ Lanterns Australia’s biggest hit of Catch When this Katy Perry- Prince, Deschanel Birds of Tokyo 2013 is starting to shine Allie X endorsed L.A.-Toronto pop through here, with a songstress sings, “Wait Prince performed this chiming keyboard hook until I catch my breath,” song with Zooey Descha- and an anthem’s chorus. she may take yours. nel on New Girl after Gimme Thrash metal collides with Say You’ll Just call her Icy Spice. the Super Bowl, and Chocolate!! J-pop super-cuteness, Be There Danish singer MØ reworks Babymetal resulting in this girl trio’s MØ the Spice Girls’ follow-up the full version is even mind-blowingly catchy to Wannabe with a chilly better. With its dynamite musical hybrid. electro-pop groove. horn chart, synthesizer Mystery Man A burst of feedback Kiss Me Dashboard Confessional’s solo and Prince’s flirtiest The Strypes heralds a frenetic, Darling Chris Carrabba brings falsetto all over a house- Yardbirds-style rave-up Twin Forks a brighter acoustic tone disco beat, this should from this Irish teen quar- to this band but still wears tet’s Snapshot, out today. his heart on his sleeve. make fans of His Purple Highness’ commercial I Wanna With chopped-up keys, The Secret Nail’s stoically sung love Get Better pop-up vocal choirs and David Nail triangle ends with one of heyday fall hard. -

Eddie B's Wedding Songs

ƒƒƒƒƒƒ ƒƒƒƒƒƒ Eddie B. & Company Presents Music For… Bridal Party Introductions Cake Cutting 1. Beautiful Day . U2 1. 1,2,3,4 (I Love You) . Plain White T’s 2. Best Day Of My Life . American Authors 2. Accidentally In Love . Counting Crows 3. Bring Em’Out . T.I. 3. Ain’t That A Kick In The Head . Dean Martin 4. Calabria . Enur & Natasja 4. All You Need Is Love . Beatles 5. Celebration . Kool & The Gang 5. Beautiful Day . U2 6. Chelsea Dagger . Fratellis 6. Better Together . Jack Johnson 7. Crazy In Love . Beyonce & Jay Z 7. Build Me Up Buttercup . Foundations 8. Don’t Stop The Party . Pitbull 8. Candyman . Christina Aguilera 9. Enter Sandman . Metalica 9. Chapel of Love . Dixie Cups 10. ESPN Jock Jams . Various Artists 10. Cut The Cake . Average White Bank 11. Everlasting Love . Carl Carlton 11. Everlasting Love . Carl Carlton & Gloria Estefan 12. Eye Of The Tiger . Survivor 12. Everything . Michael Buble 13. Feel So Close . Calvin Harris 13. Grow Old With You . Adam Sandler 14. Feel This Moment . Pitt Bull & Christina Aguilera 14. Happy Together . Turtles 15. Finally . Ce Ce Peniston 15. Hit Me With Your Best Shot . Pat Benatar 16. Forever . Chris Brown 16. Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You) . James Taylor 17. Get Ready For This . 2 Unlimited 17. I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch) Four Tops 18. Get The Party Started . Pink 18. I Got You Babe . Sonny & Cher 19. Give Me Everything Tonight . Pitbull & Ne-Yo 19. Ice Cream . Sarah McLachlan 20. Gonna Fly Now . -

Part II (Searchable PDF) (1.885Mb)

Quarantine Diaries: Day 10, Kathmandu March 29, 2020 I am losing it now. I need people in my life. And Love. Somebody sing Chori Chori Chupke Se for me like Salman Khan does in the movie Lucky. Watched that music video for the 1863th time and still there’s something in it that makes me smile. I hate my attention span. And a lot of things. But take a deep breath. And let go. You need to be there for yourself right now. Before anybody else. Day 11, Kathmandu March 30,2020 Today’s for good conversations. But like I said every day has its own universe. I am still not sure if it’s people not noticing things or not thinking it’s important enough to be shared. But whatever the case is I still believe that the fun is in the details. I still feel every emotion in its highest intensity including boredom. So when I ask you how your day was I mean tell me how much milk you added in your coffee. Tell me what song you played while cooking. And what consistency of daal you like. I care about every freaking thing that happens in a day. Everything you do is an art. And danced in my orange crop top in front of the living room’s TV. I need to create my own happiness, it's not gonna work otherwise. Now I am pushing myself to do THINGS other than just waiting for days to pass. Especially if classes start from tomorrow. And Dr B. -

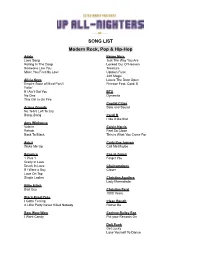

Band Song-List

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

Part II: ETA Grant Programs Financial Management

Part II Updated July 2011 One – Stop Comprehensive Financial Management Technical Assistance Guide Part II U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR Employment and Training Administration U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration Office of Grants Management Division of Policy, Review and Resolution July 2011 Update Washington, D.C. One-Stop Comprehensive Financial Management Technical Assistance Guide – Part II Contents Part II: ETA Grant Programs Financial Management .......................................................... II-Intro-1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... II-Intro-1 Intended Audience .......................................................................................................................... II-Intro-2 How Part II is Organized.................................................................................................... II-Intro-2 Cautions ......................................................................................................................... II-Intro-4 Chapter II-1: Fund Distribution ............................................................................................... II-1-1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... II-1-1 Federal Budget Process ................................................................................................................... -

New Mexico's Independent Ethics Commission and the Long Fight To

Volume 51 Issue 1 Winter Winter 2021 New Mexico’s Independent Ethics Commission and the Long Fight to Constrain Public Corruption Lane Towery University of New Mexico - School of Law Recommended Citation Lane Towery, New Mexico’s Independent Ethics Commission and the Long Fight to Constrain Public Corruption, 51 N.M. L. Rev. 275 (2021). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmlr/vol51/iss1/10 This Student Note is brought to you for free and open access by The University of New Mexico School of Law. For more information, please visit the New Mexico Law Review website: www.lawschool.unm.edu/nmlr NEW MEXICO’S INDEPENDENT ETHICS COMMISSION AND THE LONG FIGHT TO CONSTRAIN PUBLIC CORRUPTION Lane Towery ABSTRACT After a string of high-profile corruption scandals1 in state government, and a decade-long legislative fight to find a solution, in 2018 New Mexico voters passed a popular constitutional amendment creating an independent ethics commission.2 Enabling legislation cleared the legislature during the 2019 session3, and the commission began operating on January 1, 2020. The ethics commission hears complaints made against candidates, lobbyists, and public officials in the executive and legislative branches. In addition, it publishes opinions on questions of ethics in state government. The commission, however, risks failing at its mission to reduce unethical behavior because of a lack of power and gaps in underlying anti-corruption law. Part I of this comment explores the cyclical history of corruption and attempts to pass anti-corruption law in New Mexico. It then explains the legislative history behind the new ethics commission, including the constitutional amendment and enabling legislation. -

Jay-Z, Part II (On the Run) Feat. Beyonce

Jay-Z, Part II (On The Run) Feat. Beyonce [Beyoncé:] Who wants that perfect love story any way, anyway Cliché, Cliché Cliché, Cliché Who wants that hero love that saves the day, anyway Cliché, Cliché Cliché, Cliché What about the bad guy goes good, yeah And the missing missing love that's misunderstood, yeah Black hour glass, our glass Toast to clichés in a dark past Toast to clichés in a dark past [Jay-Z:] Boy meets girl, girl perfect women Girl get the bustin' before the cops come running Chunking deuces, chugging D'USSE Fuck what you say, boys in blue say [Beyoncé:] I don't care if you on the run Baby as long as I'm next to you And if loving you is a crime Tell me why do I bring out The best in you I hear sirens while we make love Loud as hell but they don't know They're nowhere near us I will hold your heart and your gun I don't care if they come, noooo I know it's crazy but They can take me Now that I found the places that you take me Without you I got nothing lose [Jay-Z:] I'm an outlaw, got an outlaw chick Bumping 2Pac, on my outlaw shit Matching tatts, this Ink don't come off Even if rings come off If things ring off My nails get dirty My past ain't pretty, my lady is, my Mercedes is My baby momma harder then a lot of you niggas Keep it 100, hit the lottery niggas You ain't about that life ain't gotta lie to me, nigga You know its till the death, I hope it (..) to niggas Cross the line, speak about mine I'mma wave this tech, I'mma geek about mine Touch a nigga where his rib at, I click clat Push your ma'fucka wig back, I did that I been wilding since a juvi She was a good girl till she knew me Now she is in the drop bussin' U'e Screaming.. -

Uniform Crime Reporting Handbook

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reporting Handbook Revised 2004 EDITORIAL NOTE: The Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program staff of the FBI worked for over three years on the revision of the UCR handbook. Individuals from the various units that make up the national UCR Program read, reviewed, and made suggestions during this long endeavor. Our goal was to make the handbook user friendly as well as educationally sound. From a pedagogical standpoint, we tried to present one concept at a time and not overwhelm the user with too much information at once. Consequently, classifying and scoring are presented in two separate chapters. The user can learn first how to classify the Part I offenses and then how to score them. For easy reference, we consolidated explanations of important UCR concepts, such as jurisdiction, hierarchy, and separation of time and place, in one chapter. We retained many of the examples with which users are already familiar, and we also updated many of the examples so they better reflect the American society of the twenty-first century. Further, where possible, we tried to align summary and National Incident- Based Reporting System (NIBRS) ideas and definitions to help emphasize that summary and NIBRS are part of the same UCR Program. Listening to suggestions from users of this manual, we added an Index as a quick-reference aid and a Glossary; however, we were cautious to retain standard UCR definitions. The national UCR Program thanks the many substance review- ers from various state UCR Programs for their time and for their constructive comments. -

Guido Culture: the Destabilization of Italian-American Identity on Jersey Shore

eScholarship California Italian Studies Title “Guido” Culture: The Destabilization of Italian-American Identity on Jersey Shore Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1m95s09q Journal California Italian Studies, 4(2) Author Troyani, Sara Publication Date 2013 DOI 10.5070/C342015780 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “Guido” Culture: The Destabilization of Italian-American Identity on Jersey Shore Sara Troyani Italian-American leaders oppose MTV’s Jersey Shore (2009-2012) on the basis that the reality television series, which chronicles the lives of eight young Italian-American men and women housemates who self-identify as “Guidos” and “Guidettes,” promotes ethnic stereotyping. While the term “Guido” has long been considered an ethnic slur against urban working-class Italian Americans in the Northeastern United States, the generationally pejorative word has been embraced by many younger Americans of Italian heritage. Like the cast of Jersey Shore, they use it to recognize practitioners of Guido style who skillfully craft their identities in response to mass-media representations of Italian-American culture. 1 Nonetheless, numerous prominent Italian Americans worry that Jersey Shore might encourage viewers to conflate Italian Americans with the Guidos they see on television. Robert Allegrini, public relations director for the National Italian American Foundation (NIAF), which promotes Italian-American culture and heritage through educational youth programs, expressed concern that viewers might “make a direct connection between ‘[G]uido culture’ and Italian-American identity.” 2 In a letter to Philippe P. Dauman, the president and CEO of MTV Networks’ parent company Viacom, written on behalf of both the Italian American Legislative Caucus and the New Jersey Italian and Italian American Heritage Commission, New Jersey State Senator Joseph F.