First Record of the Blow Fly Calliphora Grahami from Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Diptera: Calliphoridae) from India

International Journal of Entomology Research International Journal of Entomology Research ISSN: 2455-4758 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.24 www.entomologyjournals.com Volume 3; Issue 1; January 2018; Page No. 43-48 Taxonomic studies on the genus Calliphora robineau-desvoidy (Diptera: Calliphoridae) from India 1 Inderpal Singh Sidhu, *2 Rashmi Gupta, 3 Devinder Singh 1, 2 Department of Zoology, SGGS College, Sector 26, Chandigarh, Punjab, India 3 Department of Zoology and Environment Sciences, Punjabi University, Patiala, Punjab, India Abstract Four Indian species belonging to the genus Calliphora Robineau-Desvoidy have been studied and detailed descriptions have been written for each of them that include synonymy, morphological attributes, colouration, chaetotaxy, wing venation, illustrations of male and female genitalia, material examined, distribution, holotype depository and remarks. A key to the Indian species has also been provided. Keywords: India, Calliphora, calliphorinae, calliphoridae, diptera Introduction . Calliphora rufifacies Macquart, 1851. Dipt. Exot. Suppl., The genus Calliphora Robineau-Desvoidy is represented by 4: 216. four species in India (Bharti, 2011) [2]. They are medium to . Musca aucta Walker, 1853. Insect. Saund. Dipt., 1: 334. large sized flies commonly called the blue bottles. The . Calliphora insidiosa Robineau-Desvoidy, 1863 Insect. diagnostic characters of the genus include: eyes holoptic or Saund. Dipt., 1: 334. subholoptic in male, dichoptic in female; jowls about half eye . Calliphora insidiosa Robineau-Desvoidy, 1863. Posth. 2: height; facial carina absent; length of 3rd antennal segment less 695. than 4X that of 2nd; arista long plumose; propleuron and . Calliphora turanica Rohdeau-Desvoidy, 1863. Posth., 2: prosternum hairy; postalar declivity hairy; acrostichals 1-3+3; 695. -

Terry Whitworth 3707 96Th ST E, Tacoma, WA 98446

Terry Whitworth 3707 96th ST E, Tacoma, WA 98446 Washington State University E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Published in Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington Vol. 108 (3), 2006, pp 689–725 Websites blowflies.net and birdblowfly.com KEYS TO THE GENERA AND SPECIES OF BLOW FLIES (DIPTERA: CALLIPHORIDAE) OF AMERICA, NORTH OF MEXICO UPDATES AND EDITS AS OF SPRING 2017 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 Materials and Methods ................................................................................................... 5 Separating families ....................................................................................................... 10 Key to subfamilies and genera of Calliphoridae ........................................................... 13 See Table 1 for page number for each species Table 1. Species in order they are discussed and comparison of names used in the current paper with names used by Hall (1948). Whitworth (2006) Hall (1948) Page Number Calliphorinae (18 species) .......................................................................................... 16 Bellardia bayeri Onesia townsendi ................................................... 18 Bellardia vulgaris Onesia bisetosa ..................................................... -

Dating Pupae of the Blow Fly Calliphora Vicina Robineau

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Dating Pupae of the Blow Fly Calliphora vicina Robineau–Desvoidy 1830 (Diptera: Calliphoridae) for Post Mortem Interval—Estimation: Validation of Molecular Age Markers Barbara K. Zajac *, Jens Amendt, Marcel A. Verhoff and Richard Zehner Institute of Legal Medicine, Goethe University, 60596 Frankfurt, Germany; [email protected] (J.A.); [email protected] (M.A.V.); [email protected] (R.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-163-865-3366 Received: 31 December 2017; Accepted: 5 March 2018; Published: 9 March 2018 Abstract: Determining the age of juvenile blow flies is one of the key tasks of forensic entomology when providing evidence for the minimum post mortem interval. While the age determination of blow fly larvae is well established using morphological parameters, the current study focuses on molecular methods for estimating the age of blow flies during the metamorphosis in the pupal stage, which lasts about half the total juvenile development. It has already been demonstrated in several studies that the intraspecific variance in expression of so far used genes in blow flies is often too high to assign a certain expression level to a distinct age, leading to an inaccurate prediction. To overcome this problem, we previously identified new markers, which show a very sharp age dependent expression course during pupal development of the forensically-important blow fly Calliphora vicina Robineau–Desvoidy 1830 (Diptera: Calliphoridae) by analyzing massive parallel sequencing (MPS) generated transcriptome data. We initially designed and validated two quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assays for each of 15 defined pupal ages representing a daily progress during the total pupal development if grown at 17 ◦C. -

Evaluating the Effects of Temperature on Larval Calliphora Vomitoria (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Consumption

Evaluating the effects of temperature on larval Calliphora vomitoria (Diptera: Calliphoridae) consumption Kadeja Evans and Kaleigh Aaron Edited by Steven J. Richardson Abstract: Calliphora vomitoria (Diptera: Calliphoridae) are responsible for more cases of myiasis than any other arthropods. Several species of blowfly, including Cochliomyia hominivorax and Cocholiomya macellaria, parasitize living organisms by feeding on healthy tissues. Medical professionals have taken advantage of myiatic flies, Lucillia sericata, through debridement or maggot therapy in patients with necrotic tissue. This experiment analyzes how temperature influences blue bottle fly, Calliphora vomitoria. consumption of beef liver. After rearing an egg mass into first larval instars, ten maggots were placed into four containers making a total of forty maggots. One container was exposed to a range of temperatures between 18°C and 25°C at varying intervals. The remaining three containers were placed into homemade incubators at constant temperatures of 21°C, 27°C and 33°C respectively. Beef liver was placed into each container and weighed after each group pupation. The mass of liver consumed and the time until pupation was recorded. Three trials revealed that as temperature increased, the average rate of consumption per larva also increased. The larval group maintained at 33°C had the highest consumption with the shortest feeding duration, while the group at 21°C had lower liver consumption in the longest feeding period. Research in this experiment was conducted to understand the optimal temperature at which larval consumption is maximized whether in clinical instances for debridement or in myiasis cases. Keywords: Calliphora vomitoria, Calliphoridae, myiasis, consumption, debridement As an organism begins to decompose, target open wounds or necrotic tissue. -

Diptera: Calliphoridae)1

Pacific Insects 13 (1) : 141-204 15 June 1971 THE TRIBE CALLIPHORINI FROM AUSTRALIAN AND ORIENTAL REGIONS II. CALLIPHORA-GROUP (Diptera: Calliphoridae)1 By Hiromu Kurahashi Abstract: The Australian and Oriental Calliphora-group consists of the following 5 genera: Xenocalliphora Malloch (6 spp.), Aldrichina Townsend (1 sp.), T Heer atopy ga Rohdendorf (1 sp.), Eucalliphora Townsend (1 sp.) and Calliphora Rob.-Desvoidy (37 spp.). The genus Calliphora Rob.-Desvoidy has a number of members with a greater diversity of form and coloration than do those known from any other faunal region, and it is subdivided into the 5 subgenera: Neocalliphora Brauer & Bergenstamm, Cal liphora s. str., Paracalliphora Townsend, Papuocalliphora n. subgen, and Australocalli- phora n. subgen, in the present paper. The following forms are described as new: Calliphora pseudovomitoria, Paracalliphora papuensis, P. kermadeca, P. norfolka, P. augur neocaledonensis, P. espiritusanta, P. porphyrina, P. gressitti, P. rufipes kermadecensis, P. rufipes tasmanensis, P. rufipes tahitiensis, Australocalliphora onesioidea and A. tasmaniae, This second study in the series on Australian and Oriental Calliphorini presents a revision of the Calliphora-group based on a much greater amount of material than the early authors had. Most of the specimens examined were available in the Department of Entomology, Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu. I have raised the number of species to 46 which belong to 5 genera: Xenocalliphora Malloch, Aldrichina Townsend, Triceratopyga Rohdendorf, Eucalliphora Townsend and Calliphora Rob.-Desvoidy. The former 4 are either monobasic or with few species in contrast with the 38 species of the last genus. They have several plesiomorphous characters, i.e., dichoptic condition of eyes in <^, in spite of a more or less high degree of specialization with respect to some features such as hypopygium. -

Post-Feeding Larval Behaviour in the Blowfly

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Forensic Science International 177 (2008) 162–167 www.elsevier.com/locate/forsciint Post-feeding larval behaviour in the blowfly, Calliphora vicina: Effects on post-mortem interval estimates Sophie Arnott, Bryan Turner * Department of Forensic Science and Drug Monitoring, King’s College London, Franklin-Wilkins Building, 150 Stamford Street, London SE1 9NH, United Kingdom Received 9 July 2007; received in revised form 26 September 2007; accepted 5 December 2007 Available online 19 February 2008 Abstract Using the rate of development of blowflies colonising a corpse, accumulated degree hours (ADH), or days (ADD), is an established method used by forensic entomologists to estimate the post-mortem interval (PMI). Derived from laboratory experiments, their application to field situations needs care. This study examines the effect of the post-feeding larval dispersal time on the ADH and therefore the PMI estimate. Post-feeding dispersal in blowfly larvae is typically very short in the laboratory but may extend for hours or days in the field, whilst the larvae try to find a suitable pupariation site. Increases in total ADH (to adult eclosion), due to time spent dispersing, are not simply equal to the dispersal time. The pupal period is increased by approximately 2 times the length of the dispersal period. In practice, this can introduce over-estimation errors in the PMI estimate of between 1 and 2 days if the total ADH calculations do not consider the possibility of an extended larval dispersal period. # 2007 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Dispersal; Accumulated degree hours; ADH; Accumulated degree days; ADD; Forensic entomology; PMI; Blowflies; Calliphora 1. -

Test Key to British Blowflies (Calliphoridae) And

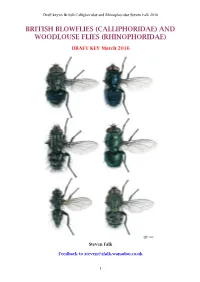

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016 BRITISH BLOWFLIES (CALLIPHORIDAE) AND WOODLOUSE FLIES (RHINOPHORIDAE) DRAFT KEY March 2016 Steven Falk Feedback to [email protected] 1 Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016 PREFACE This informal publication attempts to update the resources currently available for identifying the families Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae. Prior to this, British dipterists have struggled because unless you have a copy of the Fauna Ent. Scand. volume for blowflies (Rognes, 1991), you will have been largely reliant on Van Emden's 1954 RES Handbook, which does not include all the British species (notably the common Pollenia pediculata), has very outdated nomenclature, and very outdated classification - with several calliphorids and tachinids placed within the Rhinophoridae and Eurychaeta palpalis placed in the Sarcophagidae. As well as updating keys, I have also taken the opportunity to produce new species accounts which summarise what I know of each species and act as an invitation and challenge to others to update, correct or clarify what I have written. As a result of my recent experience of producing an attractive and fairly user-friendly new guide to British bees, I have tried to replicate that approach here, incorporating lots of photos and clear, conveniently positioned diagrams. Presentation of identification literature can have a big impact on the popularity of an insect group and the accuracy of the records that result. Calliphorids and rhinophorids are fascinating flies, sometimes of considerable economic and medicinal value and deserve to be well recorded. What is more, many gaps still remain in our knowledge. -

Key for Identification of European and Mediterranean Blowflies (Diptera, Calliphoridae) of Forensic Importance Adult Flies

Key for identification of European and Mediterranean blowflies (Diptera, Calliphoridae) of forensic importance Adult flies Krzysztof Szpila Nicolaus Copernicus University Institute of Ecology and Environmental Protection Department of Animal Ecology Key for identification of E&M blowflies, adults The list of European and Mediterranean blowflies of forensic importance Calliphora loewi Enderlein, 1903 Calliphora subalpina (Ringdahl, 1931) Calliphora vicina Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830 Calliphora vomitoria (Linnaeus, 1758) Cynomya mortuorum (Linnaeus, 1761) Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann, 1819) Chrysomya marginalis (Wiedemann, 1830) Chrysomya megacephala (Fabricius, 1794) Phormia regina (Meigen, 1826) Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830) Lucilia ampullacea Villeneuve, 1922 Lucilia caesar (Linnaeus, 1758) Lucilia illustris (Meigen, 1826) Lucilia sericata (Meigen, 1826) Lucilia silvarum (Meigen, 1826) 2 Key for identification of E&M blowflies, adults Key 1. – stem-vein (Fig. 4) bare above . 2 – stem-vein haired above (Fig. 4) . 3 (Chrysomyinae) 2. – thorax non-metallic, dark (Figs 90-94); lower calypter with hairs above (Figs 7, 15) . 7 (Calliphorinae) – thorax bright green metallic (Figs 100-104); lower calypter bare above (Figs 8, 13, 14) . .11 (Luciliinae) 3. – genal dilation (Fig. 2) whitish or yellowish (Figs 10-11). 4 (Chrysomya spp.) – genal dilation (Fig. 2) dark (Fig. 12) . 6 4. – anterior wing margin darkened (Fig. 9), male genitalia on figs 52-55 . Chrysomya marginalis – anterior wing margin transparent (Fig. 1) . 5 5. – anterior thoracic spiracle yellow (Fig. 10), male genitalia on figs 48-51 . Chrysomya albiceps – anterior thoracic spiracle brown (Fig. 11), male genitalia on figs 56-59 . Chrysomya megacephala 6. – upper and lower calypters bright (Fig. 13), basicosta yellow (Fig. 21) . Phormia regina – upper and lower calypters dark brown (Fig. -

The Breadth of Forensic Entomology

1 The breadth of forensic entomology Forensic entomology is the branch of forensic science in which information about insects is used to draw conclusions when investigating legal cases relating to both humans and wildlife, although on occasion the term may be expanded to include other arthropods. Insects can be used in the investigation of a crime scene both on land and in water (Anderson, 1995; Erzinçlioglu,˘ 2000; Keiper and Casamatta, 2001; Hobischak and Anderson, 2002; Oliveira-Costa and de Mello-Patiu, 2004). The majority of cases where entomological evidence has been used are concerned with illegal activities which take place on land and are discov- ered within a short time of being committed. Gaudry et al. (2004) commented that in France 70 % of cadavers were found outdoors and of these 60 % were less than 1 month old. The insects that can assist in forensic entomological investigations include blowflies, flesh flies, cheese skippers, hide and skin beetles, rove beetles and clown beetles. In some of these families only the juvenile stages are carrion feeders and consume a dead body. In others both the juvenile stages and the adults will eat the body (are necrophages). Yet other families of insects are attracted to the body solely because they feed on the necrophagous insects that are present. 1.1 History of forensic entomology Insects are known to have been used in the detection of crimes for a long time and a number of researchers have written about the history of forensic entomology (Benecke, 2001;COPYRIGHTED Greenberg and Kunich, 2002). MATERIAL The Chinese used the presence of flies and other insects as part of their investigative armoury for crime scene investigation and instances of their use are recorded as early as the mid-tenth century (Cheng, 1890; cited in Greenberg and Kunich, 2002). -

SPATIAL and TEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION of the FORENSICALLY SIGNIFICANT BLOW FLIES of LOS ANGELES COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, UNITED STATES (DIPTERA: CALLIPHORIDAE) Royce T

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations & Theses in Natural Resources Natural Resources, School of Spring 4-19-2019 SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE FORENSICALLY SIGNIFICANT BLOW FLIES OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, UNITED STATES (DIPTERA: CALLIPHORIDAE) Royce T. Cumming University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresdiss Part of the Entomology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Cumming, Royce T., "SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE FORENSICALLY SIGNIFICANT BLOW FLIES OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, UNITED STATES (DIPTERA: CALLIPHORIDAE)" (2019). Dissertations & Theses in Natural Resources. 284. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresdiss/284 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses in Natural Resources by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE FORENSICALLY SIGNIFICANT BLOW FLIES OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, UNITED STATES (DIPTERA: CALLIPHORIDAE) By Royce T. Cumming A THESIS Presented to the Graduate Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Natural Resource Sciences Under the Supervision of Professor Leon Higley Lincoln, Nebraska April 2018 SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE FORENSICALLY SIGNIFICANT BLOW FLIES OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, UNITED STATES (DIPTERA: CALLIPHORIDAE) Royce T. Cumming M.S. University of Nebraska, 2019 Advisor: Leon Higley Forensic entomology although not a commonly used discipline in the forensic sciences, does have its niche and when used by investigators is respected in crinimolegal investigations (Greenberg and Kunich, 2005). -

Calliphora Vicina Calliphora Vomitoria Lucilia Sericata Lucilia Richardsi

Calliphoridae and Rhiniidae Recording Scheme The Calliphoridae are a small family with only 37 species that have been recorded in Britain, and Rhiniidae – with only one: Stomorhina lunata. Many species are under-recorded and in need of further research. Blowflies are an important group, a number of species helping crime investigations – their larvae feed on carcasses and can be used to establish the post mortem interval. Some cause myiasis – a condition in which eggs are laid and larvae feed on live hosts such as people, sheep (‘sheep-strike’), birds, etc. Other Calliphoridae parasitize earth worms, slugs or snails. The adult flies pollinate plants while feeding on their flowers. There are however many things we still do not know, for example how widespread are some species and what is their biology? The Calliphoridae and Rhiniidae Recording Scheme is an initiative with the aim of recording the spatial and temporal distribution of British blowflies. The records are being gathered from iRecord, social media, from entomologists – professional and amateur, and from museum collections. Many of these are photographic records, but for a number of species keeping specimens is necessary. Some of the characters that need to be examined are too small/difficult to see on a photograph (for example coxopleural streak, some bristles) or require further preparation of the specimen (genitalia extraction). To maintain high quality of data collected majority of submitted records are being meticulously checked. Hence the importance of keeping photographs and/or specimens. Below you can see few species that can be readily identified from good quality photographs – for others taking specimens is advised. -

The Forensically Important Calliphoridae (Insecta: Diptera) of Pig Carrion in Rural North-Central Florida

THE FORENSICALLY IMPORTANT CALLIPHORIDAE (INSECTA: DIPTERA) OF PIG CARRION IN RURAL NORTH-CENTRAL FLORIDA By SUSAN V. GRUNER A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2004 Copyright 2004 by Susan V. Gruner For Jack, Rosamond, and Michael ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The successful completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the support, encouragement, understanding, guidance, and physical help of many colleagues, friends, and family. My mother, Rosamond, edited my thesis despite her obvious distaste for anything related to maggots. My husband, Michael, cheerfully allowed more than most spouses could bear. And when it got really cold outside, he only complained two or three times when I kept multiple containers of stinking liver and writhing maggots on the kitchen counter. He also took almost all of the fantastic photos presented in this thesis and for my presentation. Finally, Michael had the horrible job of inserting an arrow with twelve temperature probes into pig “E.” I am also indebted to Dan and Jenny Slone, Jon Allen, Debbie Hall, Jane and Buthene Haskell, Dan and Zane Greathouse, owners of Greathouse Butterfly Farm, Aubrey Bailey, and the National Institute of Justice. My professional colleagues, John Capinera, Marjorie Hoy, and Neal Haskell, guided and encouraged me through my research and writing every step of the way. Although I doubt that John Capinera was greatly interested in maggots, his support and enthusiasm in response to my enthusiasm are very much appreciated. Marjorie Hoy’s beneficial advice was always appreciated and on occasion, she offered a shoulder on which to cry.