Dialogue and Democracy Part 3 Final.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

PG Diploma in Police Administration (Private)

Sardar Patel University of Police, Security and Criminal Justice, Jodhpur Provisional Short Listed Candidates of Post Graduate Diploma in Police Administration (Private) S. No. Email Address Applicant's Name Father's Name 1 arvi***[email protected] ARVIND SINGH RATHORE JAGMAL SINGH RATHORE 2 rsba***[email protected] RUPENDRA SINGH PURAWAT DEVI SINGH 3 clee***[email protected] Leela Choudhary HANUMAN CHOUDHARY 4 ramj***[email protected] Ram Ji Lal jagdish 5 hafe***[email protected] HAFEEZ SAMSUDEEN 6 NEHA***[email protected] NEHA BOHRA SHYAMLAL BOHRA 7 sant***[email protected] SANTOSH KUMAWAT JAGDISH PRASAD KUMAWAT 8 abhi***[email protected] A H ABHIJITH ANIRUDHAN K 9 aabi***[email protected] AABID HUSAIN SAHABDEEN 10 aach***[email protected] aachu swami bhagwan das swami 11 aada***[email protected] AADARSH KISHOR MALA RAM 12 aaka***[email protected] Aakansha sharma Surendra kumar sharma 13 aaka***[email protected] Aakash Dourata Dharmpal Dourata 14 aara***[email protected] AARAM JAT JATAN LAL JAT 15 LUCK***[email protected] AARTI RAWAT SHAITAN SINGH RAWAT 16 aash***[email protected] Aashish sharma Radheyshyam sharma 17 kuma***[email protected] AAZAD KALOYA PURUSOTAM KUMAWAT 18 akma***[email protected] abdul ajij gafur khan 19 abha***[email protected] ABHAY SINGH HEM SINGH 20 abha***[email protected] abhay singh poonam chand 21 abha***[email protected] Abhay singh Bajrang lal 22 sahu***[email protected] Abhijeet sahu Babu lal sahu 23 abhi***[email protected] Abhimanyu Singh Amar Singh 24 sing***[email protected] ABHIMANYU -

C,2\ 04 2411 3 Telegram: Match the Following Mahajanapadas with Their Modem Names

*- \'' ' 2017 I Code : W08 BOOKLET No. - c,2\ 04 2411 3 www.mpscmaterial.com www.fb.com/mpscmaterial Telegram: www.t.me/mpscbooks Match the following Mahajanapadas with their modem names : a. Anga I. South Bihar b. Magadha 11. East Bihar c. Vajji 111. North Bihar d. Malla IV. Gorakhpur district mmnrrdt GWll I SPACE FOR ROUGH WORK P.T.O. www.mpscmaterial.com www.fb.com/mpscmaterial Telegram: www.t.me/mpscbooks a. fScm I. 7lWr3m w % Th6k-d 11. i.mer w *. * 111. Wlm rn 3. Fibla IV. +¶am 3T 3 =ti 3 (I) 111 I IV I1 (2) I1 I11 I IV (3) Iv I1 111 I (4) I IV I1 111 Match the following explorers of Sindhu civilization with cities discovered by them : a. Harappa I. Rakhaldas Bane rji b. Mohenjodaro 11. Ranganath Rao c. Chanhudaro 111. Dayaram Sahni d. Lothal IV. Gopal Majumdar Which of the following soft stones was used to make the seals in Sindhu civilization ? (1) Haematite (2) Magnetite (3) Limonite (4) Steatite I SPACE FOR ROUGH WORK www.mpscmaterial.com www.fb.com/mpscmaterial Telegram: www.t.me/mpscbooks Match the Mahajanapadas and their kings : a. Kosal I. Bimbisar b. Magadha 11. Pradyot c. Vatsa 111. Prasenjit d. Avanti Iv. Udyan a b c d (1) I I11 I1 Iv (2) I11 I Iv I1 (3) Iv I 111 I1 (4) I1 111 I Iv 5. m**rjPmhm*-? (1) m (2) mimhlq? (3) (4) -*m Which of the following Buddhist texts refer to the sixteen Mahajanapadas ? (1) Anguttar Nikaya (2) Pradnyaparmitasutra (3) Nitishastra (4) Dirgha Nikaya WWfi'&m I SPACE FOR ROUGH WORK P.T.0. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

National Law University, Delhi Sector-14, Dwarka New Delhi-110078

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI SECTOR-14, DWARKA NEW DELHI-110078 ALL INDIA LAW ENTRANCE TEST-2016 (AILET-2016), B.A. LL.B.(HONS.) RESULT Marks Wise S.No. Roll No Name of the Candidate Name of Father/Mother/ Guardian DoB Gender Marks 1 52788 KARAN DHALLA DEEPESH DHALLA 03/02/1998 M 119 2 55979 SHUBHAM JAIN BHUPENDRA JAIN 20/11/1997 M 116 3 56876 VANSH AGGARWAL PAWAN SINGHAL 25/03/1998 M 116 4 63245 ARTH NAGPAL RAJESH NAGPAL 28/08/1997 M 114 5 64122 RIJU SHRIVASTAVA YUGENDRA ARYA 27/04/1998 F 114 6 69185 ROHIL BIPIN DESHPANDE BIPIN GAJANAN DESHPANDE 10/05/1998 M 114 7 70191 ARVIND KUMAR TIWARI AKHILESH CHANDRA TIWARI 03/10/1997 M 114 8 75260 ANUBHUTI GARG ARUN GARG 13/06/1997 F 114 9 63398 EKANSH ARORA RAJESH ARORA 08/01/1997 M 113 10 66089 KARISHMA KARTHIK KARTHIK SUBRAMANIAN 06/04/1998 F 113 11 75266 ANUNA TIWARI SANJAY TIWARI 14/08/1997 F 113 12 77055 ANMOL DHAWAN SANJEEV DHAWAN 29/12/1998 M 113 13 77061 ANUKRITI KUDESHIA ANURODH KUDESHIA 27/09/1997 F 113 14 64048 PRANSHU SHUKLA SANJAY SHUKLA 24/02/1998 M 112 15 71044 NIKHIL SHARMA PRAMOD KUMAR SHARMA 21/01/1997 M 112 16 75365 AVANI AGARWAL SURENDRA KUMAR AGARWAL 28/06/1998 F 112 17 63385 DIVYA KUMAR GARG NITIN GARG 05/04/1998 M 111 18 64071 PRIYANKA CHATURVEDI D. P. CHATURVEDI 20/02/1997 F 111 19 72316 PRITHVI JOSHI ARUN JOSHI 28/10/1998 M 111 20 74213 SHIVAM SINGHANIA SUNIL SINGHANIA 27/02/1998 M 111 21 74227 SHREYA JAIPURIA BIRENDRA JAIPURIA 22/12/1997 F 111 22 77417 SREEDEVI GOPALAKRISHNAN NAIR GOPALAKRISHNAN NAIR 01/07/1997 F 111 23 50911 ANKUR SINGHAL ANIL KUMAR SINGHAL 26/12/1997 -

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 1

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 1 | 2007 Migration and Constructions of the Other Aminah Mohammad-Arif and Christine Moliner (dir.) Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/195 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.195 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Aminah Mohammad-Arif and Christine Moliner (dir.), South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 1 | 2007, « Migration and Constructions of the Other » [Online], Online since 16 October 2007, connection on 06 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/195 ; DOI:10.4000/ samaj.195 This text was automatically generated on 6 May 2019. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction. Migration and Constructions of the Other: Inter-Communal Relationships amongst South Asian Diasporas Aminah Mohammad-Arif and Christine Moliner The Volatility of the ‘Other’: Identity Formation and Social Interaction in Diasporic Environments Laurent Gayer Redefining Boundaries? The Case of South Asian Muslims in Paris’ quartier indien Miniya Chatterji Frères ennemis? Relations between Panjabi Sikhs and Muslims in the Diaspora Christine Moliner The Paradox of Religion: The (re)Construction of Hindu and Muslim Identities amongst South Asian Diasporas in the United States Aminah Mohammad-Arif Working for India or against Islam? Islamophobia in Indian American Lobbies Ingrid Therwath South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, -

News Update from Nepal, June 9, 2005

News update from Nepal, June 9, 2005 News Update from Nepal June 9, 2005 The Establishment The establishment in Nepal is trying to consolidate the authority of the state in society through various measures, such as beefing up security measures, extending the control of the administration, dismantling the base of the Maoists and calling the political parties for reconciliation. On May 27 King Gyanendra in his address called on the leaders of the agitating seven-party alliance “to shoulder the responsibility of making all democratic in- stitutions effective through free and fair elections.” He said, “We have consistently held discussions with everyone in the interest of the nation, people and democracy and will continue to do so in the future. We wish to see political parties becoming popular and effective, engaging in the exercise of a mature multiparty democracy, dedicated to the welfare of the nation and people and to peace and good governance, in accordance with people’s aspirations.” Defending the existing Constitution of Nepal 1990 the King argued, “At a time when the nation is grappling with terrorism, the shared commitment and involvement of all political parties sharing faith in democracy is essential to give permanency to the gradually im- proving peace and security situation in the country.” He added, “Necessary preparations have already been initiated to hold these elections, and activate in stages all elected bodies which have suffered a setback during the past three years.” However, King Gy- anendra reiterated that the February I decision was taken to safeguard democracy from terrorism and to ensure that the democratic form of governance, stalled due to growing disturbances, was made effective and meaningful. -

Conflict Between India and Pakistan an Encyclopedia by Lyon Peter

Conflict between India and Pakistan Roots of Modern Conflict Conflict between India and Pakistan Peter Lyon Conflict in Afghanistan Ludwig W. Adamec and Frank A. Clements Conflict in the Former Yugoslavia John B. Allcock, Marko Milivojevic, and John J. Horton, editors Conflict in Korea James E. Hoare and Susan Pares Conflict in Northern Ireland Sydney Elliott and W. D. Flackes Conflict between India and Pakistan An Encyclopedia Peter Lyon Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright 2008 by ABC-CLIO, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lyon, Peter, 1934– Conflict between India and Pakistan : an encyclopedia / Peter Lyon. p. cm. — (Roots of modern conflict) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-57607-712-2 (hard copy : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-57607-713-9 (ebook) 1. India—Foreign relations—Pakistan—Encyclopedias. 2. Pakistan-Foreign relations— India—Encyclopedias. 3. India—Politics and government—Encyclopedias. 4. Pakistan— Politics and government—Encyclopedias. I. Title. DS450.P18L86 2008 954.04-dc22 2008022193 12 11 10 9 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Production Editor: Anna A. Moore Production Manager: Don Schmidt Media Editor: Jason Kniser Media Resources Manager: Caroline Price File Management Coordinator: Paula Gerard This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. -

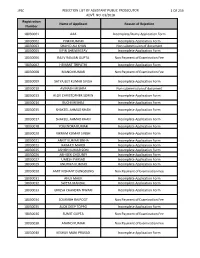

Jpsc Rejection List of Assistant Public Prosecutor 1 of 259 Advt

JPSC REJECTION LIST OF ASSISTANT PUBLIC PROSECUTOR 1 OF 259 ADVT. NO. 03/2018 Registration Name of Applicant Reason of Rejection Number 18030001 AAA Incomplete/Dumy Application Form 18030002 PINKI KUMARI Incomplete Application Form 18030003 SHAHID ALI KHAN Non submmission of document 18030005 VIPIN SHRIWASTAV Incomplete Application Form 18030006 RAJIV RANJAN GUPTA Non Payment of Examination Fee 18030007 HEMANT TRIPATHI Incomplete Application Form 18030008 MANOJ KUMAR Non Payment of Examination Fee 18030009 SATYAJEET KUMAR SINGH Incomplete Application Form 18030010 AVINASH MISHRA Non submmission of document 18030013 ALOK CHRISTOPHER SOREN Incomplete Application Form 18030014 RUCHI MISHRA Incomplete Application Form 18030015 SHAKEEL AHMAD KHAN Incomplete Application Form 18030017 SHAKEEL AHMAD KHAN Incomplete Application Form 18030018 YOGENDRA KUMAR Incomplete Application Form 18030020 VIKRAM KUMAR SINGH Incomplete Application Form 18030021 ANKIT KUMAR SINHA Incomplete Application Form 18030022 RAIMATI MARDI Incomplete Application Form 18030025 ASHISH KUMAR SONI Incomplete Application Form 18030026 ABHISEK CHOUBEY Incomplete Application Form 18030027 UMESH PARSAD Incomplete Application Form 18030029 ANUPMA KUMARI Incomplete Application Form 18030030 AMIT NISHANT DUNGDUNG Non Payment of Examination Fee 18030031 ANUJ MALIK Incomplete Application Form 18030032 SWETA MANDAL Incomplete Application Form 18030033 UMESH CHANDRA TIWARI Incomplete Application Form 18030034 SOURABH RAJPOOT Non Payment of Examination Fee 18030035 ALOK DEEP TOPPO Incomplete -

New Additions to Parliament Library

NEW ADDITIONS TO PARLIAMENT LIBRARY English Books 020 LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCES 1. Chandran, P.V., ed. Mathrubhumi yearbook plus 2016 : knowledge and beyond / edited by P.V. Chandran...[et al]. - Kozhikode: Mathrubhumi , 2016. 1025p.: plates: tables: maps; 19cm. ISBN : 978-81-8266-558-3. R 030 CHA-m B212570 Price : RS. ***250.00 080 GENERAL COLLECTIONS 2. Palat, Madhavan K., ed. Selected works of Jawaharlal Nehru / edited by Madhavan K. Palat. - New Delhi: Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund , 2015. v.; 25cm. (Second series). Contents : v.63 (1 September - 31 October 1960); v.64 (1 - 30 November 1960); Library has previous volumes. ISBN : 0-19-946590-8. 080 NEH-p B212723;v.63,B212724;v.64 100 PHILOSOPHY AND PSYCHOLOGY 3. Mukhopadhyay, Aparajita, ed. Essays on Sri Aurobindo / edited by Aparajita Mukhopadhyay. - New Delhi: Suryodaya Books , 2015. vi, 287p.; 23cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN : 978-81-925702-8-0. 181.4 Q5 B212565 Price : RS. ***990.00 200 RELIGION 4. Aczel, Amir D. Why science does not disprove God / Amir D.Aczel. - New York: William Morrow , 2014. viii, 294p.: figs.: plates; 22cm. Bibliography: p.269-281. ISBN : 978-0-06-223059-1. 215 Q4 B212718 Price : $ ***27.99 2 5. Patnaik, Devdutt My Gita / Devdutt Pattanaik. - New Delhi: Rupa Publications , 2016. 246p.: illus.; 20cm. Illustrations by the author. Reprint of 2015 ed. ISBN : 978-81-291-3770-8. 294.544 Q5 B212314 Price : RS. ***295.00 300 SOCIAL SCIENCES, SOCIOLOGY & ANTHROPOLOGY 6. Poonam Communalism in India : problems and challenges / Poonam. - New Delhi: Nisha Publications , 2016. vii, 328p.: tables; 22cm. Bibliography: p.325-326. -

List of Common Service Centres Established in Uttar Pradesh

LIST OF COMMON SERVICE CENTRES ESTABLISHED IN UTTAR PRADESH S.No. VLE Name Contact Number Village Block District SCA 1 Aram singh 9458468112 Fathehabad Fathehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 2 Shiv Shankar Sharma 9528570704 Pentikhera Fathehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 3 Rajesh Singh 9058541589 Bhikanpur (Sarangpur) Fatehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 4 Ravindra Kumar Sharma 9758227711 Jarari (Rasoolpur) Fatehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 5 Satendra 9759965038 Bijoli Bah Agra Vayam Tech. 6 Mahesh Kumar 9412414296 Bara Khurd Akrabad Aligarh Vayam Tech. 7 Mohit Kumar Sharma 9410692572 Pali Mukimpur Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 8 Rakesh Kumur 9917177296 Pilkhunu Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 9 Vijay Pal Singh 9410256553 Quarsi Lodha Aligarh Vayam Tech. 10 Prasann Kumar 9759979754 Jirauli Dhoomsingh Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 11 Rajkumar 9758978036 Kaliyanpur Rani Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 12 Ravisankar 8006529997 Nagar Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 13 Ajitendra Vijay 9917273495 Mahamudpur Jamalpur Dhanipur Aligarh Vayam Tech. 14 Divya Sharma 7830346821 Bankner Khair Aligarh Vayam Tech. 15 Ajay Pal Singh 9012148987 Kandli Iglas Aligarh Vayam Tech. 16 Puneet Agrawal 8410104219 Chota Jawan Jawan Aligarh Vayam Tech. 17 Upendra Singh 9568154697 Nagla Lochan Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 18 VIKAS 9719632620 CHAK VEERUMPUR JEWAR G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 19 MUSARRAT ALI 9015072930 JARCHA DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 20 SATYA BHAN SINGH 9818498799 KHATANA DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 21 SATYVIR SINGH 8979997811 NAGLA NAINSUKH DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 22 VIKRAM SINGH 9015758386 AKILPUR JAGER DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 23 Pushpendra Kumar 9412845804 Mohmadpur Jadon Dankaur G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 24 Sandeep Tyagi 9810206799 Chhaprola Bisrakh G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. -

Abbas KA:Khwaja Ahmed Abbas Was a Well Known Indian Journalist, Writer and Film Director. He Wrote More Than Seventy Books

INDIA Abbas K.A: Khwaja Ahmed Abbas was a well known Ahalya Bai, Rani: She was the widowed Indian journalist, writer and film director. He wrote daughter-in-law of Malhar Rao Holkar. On the latter’s more than seventy books of which Tomorrow is death, Ahalya Bai became the ruler for thirty years Ours, Invitation to Immorality, Outside India, In- till her death in 1795. dian Look at America, Defeat for Death, I am Not Ahluwalia, Montek Singh: Montek Singh Ahluwalia an Island and The Walls of Glass are very famous. is the Deputy Chairman of Planning Commission. Abdul Gaffar Khan : He was a staunch Congress- He played keyrole in financial reforms in the 1990’s. man and a soldier of the Indian freedom struggle. Previously he was Finance Secretary and member He was also called Frontier Gandhi, because he of Planning Commission. organised the people of the North West Frontier Akilandam, P.V. : P.V. Akilandam, known as Akhilan, Province (NWFP) of undivided India (now merged was a famous Tamil poet. He won Jnanapith Award with Pakistan) on Gandhian principles. He was the for his Chithira Pavai. Nengin Alaikal, first foreigner to be awarded the Bharat Ratna, Vazhvininpam and Pavai Velaku are his famous India’s highest civilian award, in 1987. He was the works. founder of the movement known as Khudai Ali, Aruna Asaf: Indian freedom fighter, Mayor of Khidmatgars (Servants of God) in 1929. Delhi, 1958. A devoted socialist, radical in her views, Bharat Ratna’97. Abdul Khadar Maulavi, Vakkom: He was a social reformer who started the daily Swadeshabhimani Ali, Salim: Indian ornithologist known as ‘the Bird- with the editorship of K.