An Analysis of Arthropod Interceptions by APHIS-PPQ and Customs and Border Protection in Puerto Rico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quadrastichus Erythrinae Kim

Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim Unusual growths caused on leaves and young shoots of coral trees (Erythrina spp.) alerts to the presence of Erythrina gall wasp (Quadrastichus erythrinae) a gall-forming eulophid wasp, that measures a mere 1.5mm and may be spread easily via infected leaves from infected Erythrina specimens. A newly described species Q. erythrinae is believed to be native to Africa. It is now a serious pest of Erythrina trees in the tropics Erythrina variegata, it is now reported in Miami and Hawaii, also knownand sub-tropics; from Singapore, it was firstMauritius collected and in Reunion. Florida onTaiwan, coral Hongtrees Kong, China, India, Thailand, Philippines, American Samoa, Guam and in the Amami Islands and Okinawa in Japan Erythrina spp. have a variety of functions in different locations. activities. As indicated by its Latin name “erythros” meaning red, In Taiwan they are highly associated with farming and fishing its obvious red flowers have been used as a sign of the arrival of spring and as a working calendar by tribal peoples. Specifically, peoplethe blooming (the Puyama of its showy people) red to flowers plant sweetsignal potatoesto the coastal (Yang people et al. 2004).to begin their ceremonies for catching flying fish, and for another Photo credit: Kim & Forest Starr The Erythrina gall wasp infests E. variegata, E. crista-galli and the Short-term control options are limited. The application of a systemic native E. sandwicensis in Hawaii (Heu et al. 2006). E. sandwicensi, insecticide appears to have been partly effective in protecting known as the wiliwili tree, is endemic to Hawaii and a keystone highly valued individual trees in Hawaii. -

Erythrina Gall Wasp, Quadrastichus Erythrinae Kim, in Florida

FDACS-P-01700 Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry Charles H. Bronson, Commissioner of Agriculture Erythrina Gall Wasp, Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim, in Florida James Wiley, [email protected], Taxonomic Entomologist, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Divsion of Plant Industry Paul Skelley, [email protected], Taxonomic Entomologist, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry INTRODUCTION: Galls of the eulophid erythrina gall wasp, Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim 2004, were first collected in Florida by Edward Putland and Olga Garcia (Florida Department of Agriculture, Division of Plant Industry) on Erythrina variegata L. in Miami-Dade County at the Miami Metro Zoo on October 15, 2006. Erythrina variegata, also known as coral tree, tiger’s claw, Japanese coral tree, Indian coral tree, and wiliwili-haole, is noted for its seasonal showy red flowers and variegated leaves. It is an ornamental landscape tree widely planted in the southern part of the state. Erythrina is a large genus with approximately 110 different species worldwide. In addition to Erythrina variegata, the erythrina gall wasp has been collected on E. crista-galli L., E. sandwicensis Deg., and E. stricta Roxb. It is uncertain at this time how many species of Erythrina the erythrina gall wasp may attack in Florida. DISTRIBUTION: The erythrina gall wasp is believed to have originated in Africa, but this remains uncertain. It was described (Kim et al 2004) from specimens from Singapore, Mauritius, and Reunion. In the past two years, it has spread to China, India, Taiwan, Philippines, and Hawaii (Heu et al 2006; Schmaedick et al 2006; ISSG 2006). -

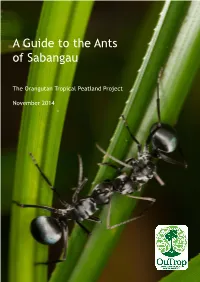

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project November 2014 A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau All original text, layout and illustrations are by Stijn Schreven (e-mail: [email protected]), supple- mented by quotations (with permission) from taxonomic revisions or monographs by Donat Agosti, Barry Bolton, Wolfgang Dorow, Katsuyuki Eguchi, Shingo Hosoishi, John LaPolla, Bernhard Seifert and Philip Ward. The guide was edited by Mark Harrison and Nicholas Marchant. All microscopic photography is from Antbase.net and AntWeb.org, with additional images from Andrew Walmsley Photography, Erik Frank, Stijn Schreven and Thea Powell. The project was devised by Mark Harrison and Eric Perlett, developed by Eric Perlett, and coordinated in the field by Nicholas Marchant. Sample identification, taxonomic research and fieldwork was by Stijn Schreven, Eric Perlett, Benjamin Jarrett, Fransiskus Agus Harsanto, Ari Purwanto and Abdul Azis. Front cover photo: Workers of Polyrhachis (Myrma) sp., photographer: Erik Frank/ OuTrop. Back cover photo: Sabangau forest, photographer: Stijn Schreven/ OuTrop. © 2014, The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project. All rights reserved. Email [email protected] Website www.outrop.com Citation: Schreven SJJ, Perlett E, Jarrett BJM, Harsanto FA, Purwanto A, Azis A, Marchant NC, Harrison ME (2014). A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project, Palangka Raya, Indonesia. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of OuTrop’s partners or sponsors. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project is registered in the UK as a non-profit organisation (Company No. 06761511) and is supported by the Orangutan Tropical Peatland Trust (UK Registered Charity No. -

Wiliwili Gall Wasp Invasion Length: One Class Period with Optional Homework Assignment

Activity #6 Invasive Species Unit 3 Activity #6 Wiliwili Gall Wasp Invasion Length: One class period with optional homework assignment Prerequisite Activity: None Objectives: • Trace the path of the 2005 wiliwili gall wasp invasion on Maui using real-life data. • Identify vectors ad pathways that facilitate the spread of invasive species. • Devise strategies for stopping an invasive pest. • Predict the efficacy of control strategies, based on existing and plausible environmental factors. Vocabulary: biological control (or biocontrol) Erythrina gall wasp (EGW) deciduous vector dormancy ••• Class Period One: Exploring the Gall Wasp Invasion on Google Earth In Advance This exercise requires access to Google Earth (free software available for download at www.earth. google.com) and the Wiliwili Gall Wasp Hoike.kmz file (included with this curriculum and available for download at www.hoikecurriculum.org). It’s best to pre-load computers with the program and file, rather than use class time to do so. Ideally students will work in small groups at their own computers as you lead them through the lesson, using a projector and screen. If that’s not possible, a single computer and projector will suffice. Prior to teaching the lesson, open Google Earth. If you’re using the software for the first time, take a few moments to learn how zoom, pan, search, etc. using the “Navigating Google Earth” tutorial avail- able at www.earth.google.com. It is best, though not necessary, to use Google Earth while connected to the Internet. Explore the Wiliwili Gall -

A New Species of Quadrastichus (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae): a Gall-Inducing Pest on Erythrina (Fabaceae)

J. HYM. RES. Vol. 13(2), 2004, pp. 243–249 A New Species of Quadrastichus (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae): A Gall-inducing Pest on Erythrina (Fabaceae) IL-KWON KIM, GERARD DELVARE, AND JOHN LA SALLE (IKK, JLS) CSIRO Entomology, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia; email: [email protected] (GD) CIRAD TA 40L, Campus International de Baillarguet-Csiro, 34398 Montpellier Cedex 5, France; email: [email protected] Abstract.—Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim sp.n. is described from Singapore, Mauritius and Re´- union. This species forms galls on the leaves, stems, petioles and young shoots of Erythrina var- iegata and E. fusca in Singapore, on the leaves of E. indica in Mauritius, and on Erythrina sp. in Re´union. It can cause extensive damage to the trees. Key words.—Hymenoptera, Eulophidae, Quadrastichus, phytophagous, gall inducer, Singapore, Mauritius, Erythrina, Fabaceae Species of Eulophidae are mainly para- 1988; Redak and Bethke 1995; Headrick et sitoids, but secondary phytophagy in the al. 1995); Epichrysocharis burwelli Schauff form of gall induction has arisen on many (Schauff and Garrison 2000); and Leptocybe occasions (Boucˇek 1988; La Salle 1994; invasa Fisher & La Salle (Mendel et al. Headrick et al. 1995; Mendel et al. 2004; 2004). Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim sp.n. La Salle 2004). Gall-inducing Eulophidae has recently achieved pest status in Sin- generally belong to two groups: Opheli- gapore, Mauritius and Re´union. Erythrina mini is an Australian lineage which con- trees have been grown in these areas for sists mainly of gall inducers on eucalypts, decades, and this species has never been but perhaps also on some other myrta- recorded from them. -

Risks from Unknown Quarantine Organisms Posed by The

Recommendation of a Pathway Approach for Regulation of Plants for Planting A Concept Paper from the IUFRO Unit on Alien Invasive Species and International Trade* Issue: A Pathway Approach Is Needed Many forest pests have been introduced into new locations on plants for planting. Mounting scientific evidence suggests that the current pest-by-pest regulatory approach and reliance on inspection to detect pests is untenable in today’s global marketplace. Much recent experience demonstrates the need to curtail the introduction of plant pests that are present in an exporting territory but not yet known to science. Therefore, the forest entomology and pathology science community recommends a pathway approach to regulating nursery stock, similar to that adopted for wood packaging material (WPM). Best management practices effective at preventing known pests will significantly reduce the risk of introducing unknown pests as well. Introduction and Scope There are three problems with the current phytosanitary regulatory approach: 1) It relies on inspection, but the volume of world trade has expanded far beyond inspection capacity. 2) It focuses on addressing the risks associated with known quarantine organisms, but most pests introduced on plants for planting are previously unknown or unpredictably aggressive pests. 3) Article VI.2 of the IPPC prohibits requiring phytosanitary measures against unregulated pests. The limitations of current measures were accepted long ago to prevent the misuse of phytosanitary concerns as artificial barriers to trade. In the ensuing years, however, it has become evident that WPM and plants for planting routinely provide pathways for unanticipated pests. With the adoption of ISPM-15 (FAO, 2002), the exchange of known and unknown pests via WPM has been significantly reduced. -

Worldwide Spread of the Difficult White-Footed Ant, Technomyrmex Difficilis (Hymeno- Ptera: Formicidae)

Myrmecological News 18 93-97 Vienna, March 2013 Worldwide spread of the difficult white-footed ant, Technomyrmex difficilis (Hymeno- ptera: Formicidae) James K. WETTERER Abstract Technomyrmex difficilis FOREL, 1892 is apparently native to Madagascar, but began spreading through Southeast Asia and Oceania more than 60 years ago. In 1986, T. difficilis was first found in the New World, but until 2007 it was mis- identified as Technomyrmex albipes (SMITH, 1861). Here, I examine the worldwide spread of T. difficilis. I compiled Technomyrmex difficilis specimen records from > 200 sites, documenting the earliest known T. difficilis records for 33 geographic areas (countries, island groups, major islands, and US states), including several for which I found no previously published records: the Bahamas, Honduras, Jamaica, the Mascarene Islands, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Africa, and Washington DC. Almost all outdoor records of Technomyrmex difficilis are from tropical areas, extending into the subtropics only in Madagascar, South Africa, the southeastern US, and the Bahamas. In addition, there are several indoor records of T. dif- ficilis from greenhouses at zoos and botanical gardens in temperate parts of the US. Over the past few years, T. difficilis has become a dominant arboreal ant at numerous sites in Florida and the West Indies. Unfortunately, T. difficilis ap- pears to be able to invade intact forest habitats, where it can more readily impact native species. It is likely that in the coming years, T. difficilis will become increasingly more important as a pest in Florida and the West Indies. Key words: Biogeography, biological invasion, exotic species, invasive species. Myrmecol. News 18: 93-97 (online 19 February 2013) ISSN 1994-4136 (print), ISSN 1997-3500 (online) Received 28 November 2012; revision received 7 January 2013; accepted 9 January 2013 Subject Editor: Florian M. -

Technomyrmex Difficilis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the West Indies

428 Florida Entomologist 91(3) September 2008 TECHNOMYRMEX DIFFICILIS (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) IN THE WEST INDIES JAMES K. WETTERER Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University, 5353 Parkside Drive, Jupiter, FL 33458 ABSTRACT Technomyrmex difficilis Forel is an Old World ant often misidentified as the white-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes (Smith). The earliest New World records of T. difficilis are from Miami-Dade County, Florida, collected beginning in 1986. Since then, it has been found in at least 22 Florida counties. Here, I report T. difficilis from 5 West Indian islands: Antigua, Nevis, Puerto Rico, St. Croix, and St. Thomas. Colonies were widespread only on St. Croix. It is probable that over the next few years T. difficilis will become increasingly important as a pest in Florida and the West Indies. Key Words: exotic species, Technomyrmex difficilis, pest ants, West Indies RESUMEN El Technomyrmex difficilis Forel es una hormiga del Mundo Antiguo que a menudo es mal identificada como la hormiga de patas blancas, Technomyrmex albipes (Smith). Los registros mas viejos de T. difficilis son del condado de Miami-Dade, Florida, recolectadas en el princi- pio de 1986. Desde entonces, la hormiga ha sido encontrada en por lo menos 22 condados de la Florida. Aquí, informo de la presencia de T. difficilis en 5 islas del Caribe: Antigua, Nevis, Puerto Rico, St. Croix y St. Thomas. Las colonias solamente fueron muy exparcidas en St. Croix. Es probable que la importancia de T. difficilis como plaga va a aumentar durante los proximos años en la Florida y el Caribe. The white-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes MATERIALS AND METHODS (Smith), has long been considered a pest in many parts of the world. -

Ants - White-Footed Ant (360)

Pacific Pests and Pathogens - Fact Sheets https://apps.lucidcentral.org/ppp/ Ants - white-footed ant (360) Photo 1. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex species, Photo 2. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex species, tending an infestation of Icerya seychellarum on tending an infestation of mealybugs on noni (Morinda avocado for their honeydew. citrifolia) for their honeydew. Photo 3. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes, side Photo 4. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes, view. from above. Photo 5. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes; view of head. Common Name White-footed ant; white-footed house ant. Scientific Name Technomyrmex albipes. Identification of the ant requires expert examination as there are several other species that are similar. Many specimens previously identified as Technomyrmex albipes have subsequently been reidentified as Technomyrmex difficilis (difficult white-footed ant) or as Technomyrmex vitiensis (Fijian white-footed ant), which also occurs worldwide. Distribution Worldwide. Asia, Africa, North and South America (restricted), Caribbean, Europe (restricted), Oceania. It is recorded from Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Guam, Marshall Islands, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Pitcairn, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Wallis and Futuna. Hosts Tent-like nests made of debris occur on the ground within leaf litter, under stones or wood, among leaves of low vegetation, in holes, crevices and crotches of stems and trunks, in the canopies of trees, and on fruit. The ants also make nests in wall cavities of houses, foraging in kitchens and bathrooms. Symptoms & Life Cycle Damage to plants is not done directly by Technomyrmex albipes, but indirectly. The ants feed on honeydew of aphids, mealybugs, scale insects and whiteflies, and prevent the natural enemies of these pests from attacking them. -

Ergatomorph Wingless Males in Technomyrmex Vitiensis Mann, 1921 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

JHR 53: 25–34 (2016) Ergatomorph wingless males in Technomyrmex vitiensis ... 25 doi: 10.3897/jhr.53.8904 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://jhr.pensoft.net Ergatomorph wingless males in Technomyrmex vitiensis Mann, 1921 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Pavel Pech1, Aleš Bezděk2 1 Faculty of Science, University of Hradec Králové, Rokitanského 62, 500 03 Hradec Králové, Czech Republic 2 Biology Centre CAS, Institute of Entomology, Branišovská 31, 370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic Corresponding author: Pavel Pech ([email protected]) Academic editor: M. Ohl | Received 19 April 2016 | Accepted 1 August 2016 | Published 19 December 2016 http://zoobank.org/2EFE69ED-83D7-4577-B3EF-DCC6AAA4457D Citation: Pech P, Bezděk A (2016) Ergatomorph wingless males in Technomyrmex vitiensis Mann, 1921 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of Hymenoptera Research 53: 25–34. https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.53.8904 Abstract Ergatomorph wingless males are known in several species of the genus Technomyrmex Mayr, 1872. The first record of these males is given inT. vitiensis Mann, 1921. In comparison with winged males, wingless males have a smaller thorax and genitalia, but both forms have ocelli and the same size of eyes. Wingless males seem to form a substantial portion (more than 10%) of all adults in examined colony fragments. Wingless males are present in colonies during the whole year, whereas the presence of winged males seems to be limited by season. Wingless males do not participate in the taking care of the brood and active forag- ing outside the nest. Males of both types possess metapleural gland openings. Beside males with normal straight scapes, strange hockey stick-like scapes have been observed in several males. -

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Quadrastichus Erythrinae Global Invasive Species Database (GISD) 2021. Species Profile Quadrastichus Erythrina

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Quadrastichus erythrinae Quadrastichus erythrinae System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Arthropoda Insecta Hymenoptera Eulophidae Common name erythrina gall wasp (EGW) (English), erythrina gall wasp (English) Synonym Similar species Summary Unusual growths, caused by the Erythrina gall wasp (Quadrastichus erythrinae), on leaves and young shoots of coral trees (Erythrina spp). alerts to the presence of this emerging invasive species. Q. erythrinae measures a mere 1.5mm and may be spread easily via infected leaves from infected Erythrina specimens. view this species on IUCN Red List Species Description Female: Length 1.45–1.6 mm. Dark brown with yellow markings. Head yellow, except gena posteriorly brown. Antenna pale brown except scape posteriorly pale. Pronotum dark brown. The mid lobe of mesoscutum with a ‘‘V’’ shaped or inverted triangular dark brown area from anterior margin, the remainder yellow. Scapula yellow. Scutellum, axilla and dorsellum brown to light brown. Propodeum dark brown. Gaster brown. Fore and hind coxae brown. Mid coxa almost pale. Femora mostly brown to light brown. Specimens from Mauritius are generally darker than those from Singapore. Oviposter sheath not protruding, short in dorsal view (Kim Delvare and La Salle 2004). Male. Length 1.0–1.15 mm. Pale coloration white to pale yellow as opposed to yellow in female. Head and antenna pale. Pronotum dark brown (but in lateral view, only upper half dark brown; lower half yellow to white). Scutellum and dorsellum pale brown. Axilla pale. Propodeum dark brown. Gaster in anterior half pale; remainder dark brown. Legs all pale. Antenna with 4 funicular segments; without the whorl of setae; F1 distinctly shorter than the other segments and slightly transverse; about 1.4 wider than long. -

Surveying for Terrestrial Arthropods (Insects and Relatives) Occurring Within the Kahului Airport Environs, Maui, Hawai‘I: Synthesis Report

Surveying for Terrestrial Arthropods (Insects and Relatives) Occurring within the Kahului Airport Environs, Maui, Hawai‘i: Synthesis Report Prepared by Francis G. Howarth, David J. Preston, and Richard Pyle Honolulu, Hawaii January 2012 Surveying for Terrestrial Arthropods (Insects and Relatives) Occurring within the Kahului Airport Environs, Maui, Hawai‘i: Synthesis Report Francis G. Howarth, David J. Preston, and Richard Pyle Hawaii Biological Survey Bishop Museum Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817 USA Prepared for EKNA Services Inc. 615 Pi‘ikoi Street, Suite 300 Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96814 and State of Hawaii, Department of Transportation, Airports Division Bishop Museum Technical Report 58 Honolulu, Hawaii January 2012 Bishop Museum Press 1525 Bernice Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i Copyright 2012 Bishop Museum All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America ISSN 1085-455X Contribution No. 2012 001 to the Hawaii Biological Survey COVER Adult male Hawaiian long-horned wood-borer, Plagithmysus kahului, on its host plant Chenopodium oahuense. This species is endemic to lowland Maui and was discovered during the arthropod surveys. Photograph by Forest and Kim Starr, Makawao, Maui. Used with permission. Hawaii Biological Report on Monitoring Arthropods within Kahului Airport Environs, Synthesis TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents …………….......................................................……………...........……………..…..….i. Executive Summary …….....................................................…………………...........……………..…..….1 Introduction ..................................................................………………………...........……………..…..….4