Weekofjune15sophomoreusi.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heroes of the Colored Race by Terry Ann Wildman Grade Level

Lesson Plan #2 for the Genius of Freedom: Heroes of the Colored Race by Terry Ann Wildman Grade Level: Upper elementary or middle school Topics: African American leaders Pennsylvania History Standards: 8.1.6 B, 8.2.9 A, 8.3.9 A Pennsylvania Core Standards: 8.5.6-8 A African American History, Prentice Hall textbook: N/A Overview: What is a hero? What defines a hero in one’s culture may be different throughout time and place. Getting our students to think about what constitutes a hero yesterday and today is the focus of this lesson. In the lithograph Heroes of the Colored Race there are three main figures and eight smaller ones. Students will explore who these figures are, why they were placed on the picture in this way, and the background images of life in America in the 1800s. Students will brainstorm and choose heroes of the African American people today and design a similar poster. Materials: Heroes of the Colored Race, Philadelphia, 1881. Biography cards of the 11 figures in the image (attached, to be printed out double-sided) Smartboard, whiteboard, or blackboard Computer access for students Poster board Chart Paper Markers Colored pencils Procedure: 1. Introduce the lesson with images of modern superheroes. Ask students to discuss why these figures are heroes. Decide on a working definition of a hero. Note these qualities on chart paper and display throughout the lesson. 2. Present the image Heroes of the Colored Race on the board. Ask what historic figures students recognize and begin to list those on the board. -

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “THAT OUR GOVERNMENT MAY STAND”: AFRICAN AMERICAN POLITICS IN THE POSTBELLUM SOUTH, 1865-1901 By LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Mia Bay and Ann Fabian and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “That Our Government May Stand”: African American Politics in the Postbellum South, 1865-1913 by LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO Dissertation Director: Mia Bay and Ann Fabian This dissertation provides a fresh examination of black politics in the post-Civil War South by focusing on the careers of six black congressmen after the Civil War: John Mercer Langston of Virginia, James Thomas Rapier of Alabama, Robert Smalls of South Carolina, John Roy Lynch of Mississippi, Josiah Thomas Walls of Florida, and George Henry White of North Carolina. It examines the career trajectories, rhetoric, and policy agendas of these congressmen in order to determine how effectively they represented the wants and needs of the black electorate. The dissertation argues that black congressmen effectively represented and articulated the interests of their constituents. They did so by embracing a policy agenda favoring strong civil rights protections and encompassing a broad vision of economic modernization and expanded access for education. Furthermore, black congressmen embraced their role as national leaders and as spokesmen not only for their congressional districts and states, but for all African Americans throughout the South. -

Nominees and Bios

Nominees for the Virginia Emancipation Memorial Pre‐Emancipation Period 1. Emanuel Driggus, fl. 1645–1685 Northampton Co. Enslaved man who secured his freedom and that of his family members Derived from DVB entry: http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Driggus_Emanuel Emanuel Driggus (fl. 1645–1685), an enslaved man who secured freedom for himself and several members of his family exemplified the possibilities and the limitations that free blacks encountered in seventeenth‐century Virginia. His name appears in the records of Northampton County between 1645 and 1685. He might have been the Emanuel mentioned in 1640 as a runaway. The date and place of his birth are not known, nor are the date and circumstances of his arrival in Virginia. His name, possibly a corruption of a Portuguese surname occasionally spelled Rodriggus or Roddriggues, suggests that he was either from Africa (perhaps Angola) or from one of the Caribbean islands served by Portuguese slave traders. His first name was also sometimes spelled Manuell. Driggus's Iberian name and the aptitude that he displayed maneuvering within the Virginia legal system suggest that he grew up in the ebb and flow of people, goods, and cultures around the Atlantic littoral and that he learned to navigate to his own advantage. 2. James Lafayette, ca. 1748–1830 New Kent County Revolutionary War spy emancipated by the House of Delegates Derived from DVB/ EV entry: http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Lafayette_James_ca_1748‐1830 James Lafayette was a spy during the American Revolution (1775–1783). Born a slave about 1748, he was a body servant for his owner, William Armistead, of New Kent County, in the spring of 1781. -

The Voting Rights Act and Mississippi: 1965–2006

THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT AND MISSISSIPPI: 1965–2006 ROBERT MCDUFF* INTRODUCTION Mississippi is the poorest state in the union. Its population is 36% black, the highest of any of the fifty states.1 Resistance to the civil rights movement was as bitter and violent there as anywhere. State and local of- ficials frequently erected obstacles to prevent black people from voting, and those obstacles were a centerpiece of the evidence presented to Con- gress to support passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.2 After the Act was passed, Mississippi’s government worked hard to undermine it. In its 1966 session, the state legislature changed a number of the voting laws to limit the influence of the newly enfranchised black voters, and Mississippi officials refused to submit those changes for preclearance as required by Section 5 of the Act.3 Black citizens filed a court challenge to several of those provisions, leading to the U.S. Supreme Court’s watershed 1969 de- cision in Allen v. State Board of Elections, which held that the state could not implement the provisions, unless they were approved under Section 5.4 Dramatic changes have occurred since then. Mississippi has the high- est number of black elected officials in the country. One of its four mem- bers in the U.S. House of Representatives is black. Twenty-seven percent of the members of the state legislature are black. Many of the local gov- ernmental bodies are integrated, and 31% of the members of the county governing boards, known as boards of supervisors, are black.5 * Civil rights and voting rights lawyer in Mississippi. -

Civil War and Reconstruction Exhibit to Have Permanent Home at National Constitution Center, Beginning May 9, 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Annie Stone, 215-409-6687 Merissa Blum, 215-409-6645 [email protected] [email protected] CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION EXHIBIT TO HAVE PERMANENT HOME AT NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER, BEGINNING MAY 9, 2019 Civil War and Reconstruction: The Battle for Freedom and Equality will explore constitutional debates at the heart of the Second Founding, as well as the formation, passage, and impact of the Reconstruction Amendments Philadelphia, PA (January 31, 2019) – On May 9, 2019, the National Constitution Center’s new permanent exhibit—the first in America devoted to exploring the constitutional debates from the Civil War and Reconstruction—will open to the public. The exhibit will feature key figures central to the era— from Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass to John Bingham and Harriet Tubman—and will allow visitors of all ages to learn how the equality promised in the Declaration of Independence was finally inscribed in the Constitution by the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, collectively known as the Reconstruction Amendments. The 3,000-square-foot exhibit, entitled Civil War and Reconstruction: The Battle for Freedom and Equality, will feature over 100 artifacts, including original copies of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, Dred Scott’s signed petition for freedom, a pike purchased by John Brown for an armed raid to free enslaved people, a fragment of the flag that Abraham Lincoln raised at Independence Hall in 1861, and a ballot box marked “colored” from Virginia’s first statewide election that allowed black men to vote in 1867. The exhibit will also feature artifacts from the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia—one of the most significant Civil War collections in the country—housed at and on loan from the Gettysburg Foundation and The Union League of Philadelphia. -

Hiram Rhodes Revels 1827–1901

FORMER MEMBERS H 1870–1887 ������������������������������������������������������������������������ Hiram Rhodes Revels 1827–1901 UNITED STATES SENATOR H 1870–1871 REPUBLICAN FROM MIssIssIPPI freedman his entire life, Hiram Rhodes Revels was the in Indiana, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, and Tennessee. A first African American to serve in the U.S. Congress. Although Missouri forbade free blacks to live in the state With his moderate political orientation and oratorical skills for fear they would instigate uprisings, Revels took a honed from years as a preacher, Revels filled a vacant seat pastorate at an AME Church in St. Louis in 1853, noting in the United States Senate in 1870. Just before the Senate that the law was “seldom enforced.” However, Revels later agreed to admit a black man to its ranks on February 25, revealed he had to be careful because of restrictions on his Republican Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts movements. “I sedulously refrained from doing anything sized up the importance of the moment: “All men are that would incite slaves to run away from their masters,” he created equal, says the great Declaration,” Sumner roared, recalled. “It being understood that my object was to preach “and now a great act attests this verity. Today we make the the gospel to them, and improve their moral and spiritual Declaration a reality. The Declaration was only half condition even slave holders were tolerant of me.”5 Despite established by Independence. The greatest duty remained his cautiousness, Revels was imprisoned for preaching behind. In assuring the equal rights of all we complete to the black community in 1854. -

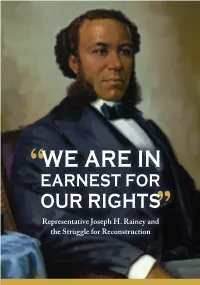

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

Influential African Americans in History

Influential African Americans in History Directions: Match the number with the correct name and description. The first five people to complete will receive a prize courtesy of The City of Olivette. To be eligible, send your completed worksheet to Kiana Fleming, Communications Manager, at [email protected]. __ Ta-Nehisi Coates is an American author and journalist. Coates gained a wide readership during his time as national correspondent at The Atlantic, where he wrote about cultural, social, and political issues, particularly regarding African Americans and white supremacy. __ Ella Baker was an essential activist during the civil rights movement. She was a field secretary and branch director for the NAACP, a key organizer for Martin Luther King Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and was heavily involved in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC prioritized nonviolent protest, assisted in organizing the 1961 Freedom Rides, and aided in registering Black voters. The Ella Baker Center for Human Rights exists today to carry on her legacy. __ Ernest Davis was an American football player, a halfback who won the Heisman Trophy in 1961 and was its first African-American recipient. Davis played college football for Syracuse University and was the first pick in the 1962 NFL Draft, where he was selected by the Cleveland Browns. __ In 1986, Patricia Bath, an ophthalmologist and laser scientist, invented laserphaco—a device and technique used to remove cataracts and revive patients' eyesight. It is now used internationally. __ Charles Richard Drew, dubbed the "Father of the Blood Bank" by the American Chemical Society, pioneered the research used to discover the effective long-term preservation of blood plasma. -

Finding Freedom in New Bedford

Finding Freedom in New Bedford On Site Pre-Visit Post-Visit Journey 1 Journey 2 Journey 3 Handouts National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Finding Freedom in New Bedford New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park When Samuel Nixon escaped from slavery to New Bedford, Massachusetts, in the early summer of 1855, he took the name Thomas Bayne and found “many old friends” from his native Norfolk, Virginia, already living in the small but bustling port city. By that time New Bedford was considered “one of the greatest assylums [sic] of the fugitives,” as whaling merchant Charles W. Morgan put it; to runaway slaves like George Teamoh, the city was “our magnet of attraction.” This curriculum-based lesson plan is one in a Included in this lesson are several pages of thematic set on the Underground Railroad supporting material. To help identify these using lessons from other National Parks. pages the following icons may be used: Also are: Hampton National Historic Site To indicate a Primary Source page Hampton Mansion: Power Struggles in Early America To indicate a Secondary Source page To Indicate a Student handout To print individual documents in this set right click the name in the bookmark on left and select To indicate a Teacher resource print pages. Finding Freedom in New Bedford Page 1 of 6 New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park National Park Service New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park tells the story of New Bedford the mid-19th century’s preeminent whaling port and for a time “the richest city in the world.” The whaling industry employed large numbers of African- Americans, Azoreans, and Cape Verdeans. -

Hiram Revels—The First African American Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels Was Born in North Carolina in the Year 11 1827

Comprehension and Fluency Name Read the passage. Use the ask and answer questions strategy to help you understand the text. Hiram Revels—The First African American Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels was born in North Carolina in the year 11 1827. Through his whole life he was a good citizen. He was a 24 great leader. He was highly respected. Revels became the first 34 African American to serve in the U.S. Senate. 42 A Hard Time for African Americans 48 Revels was born during a hard time for African Americans. 58 African Americans were treated badly. Most African Americans 66 in the South were enslaved. But Revels grew up as a free African 79 American, or freedman. This meant he could make his own 89 choices. 90 Still, the laws in the South were unfair. African Americans 100 had to work hard jobs. They were not allowed to go to school. 113 Though it was not legal, some freedmen ran schools for African 124 American children. As a child, Revels went to one of these 135 schools. But he was unable to go to college in the South. So he 149 left home to go to college in the North. Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 158 Preaching and Teaching 161 After college, Revels became the pastor of a church. He was 172 a good speaker. He was also a great teacher. He travelled all over 185 the country. He taught fellow African Americans. He knew that 195 this would make them good citizens. Practice • Grade 3 • Unit 5 • Week 4 233 Comprehension and Fluency Name The First African American Senator Revels moved to Natchez, Mississippi in 1866. -

Senate Roster

1 Mississippi State Senate 2018 Post Office Box 1018 Jackson Mississippi 39215-1018 January 28, 2019 Juan Barnett District 34 Economic Development (V); D * Room 407 jbarnett Post Office Box 407 Forrest, Jasper, Agriculture; Constitution; S Office:(601)359-3221 @senate.ms.gov Heidelberg MS 39439 Jones Environment Prot, Cons & Water S Fax: (601)359-2166 Res; Finance; Judiciary, Division A; Municipalities; Veterans & Military Affairs Barbara Blackmon District 21 Enrolled Bills (V); County Affairs; D Room 213-F bblackmon 907 W. Peace Street Attala, Holmes, Executive Contingent Fund; S Office:(601)359-3237 @senate.ms.gov Canton MS 39046 Leake, Madison, Finance; Highways & S Fax: (601)359-2879 Yazoo Transportation; Insurance; Judiciary, Division A; Medicaid Kevin Blackwell District 19 Elections (C); Insurance (V); R * Room 212-B kblackwell Post Office Box 1412 DeSoto, Marshall Accountability, Efficiency & S Office:(601)359-3234 @senate.ms.gov Southaven MS 38671 Transparency; Business & S Fax: (601)359-5345 Financial Institutions; Drug Policy; Economic Development; Education; Finance; Medicaid; PEER David Blount District 29 Public Property (C); Elections (V); D Room 213-D dblount 1305 Saint Mary Street Hinds Accountability,Efficiency, S Office: (601)359-3232 @senate.ms.gov Jackson MS 39202 Transparency; Education; Ethics; S Fax: (601)359-5957 Finance; Judiciary, Division B; Public Health & Welfare Jenifer Branning District 18 Forestry (V); Agriculture; R * Room 215 jbranning 235 West Beacon Street Leake, Neshoba, Appropriations; Business & S -

Post-Emancipation Nominees

Nominees for the Virginia Emancipation Memorial Emancipation to Present Categorized Thematically Most of the nominees could appear in more than one category. I attempted to assign them to the area of endeavor for which they are best known. For highly accomplished individuals, this was extremely difficult and admittedly subjective. For instance, there are many ministers on the list, but in my view quite a few of them fit more comfortably under “Civil Rights Era Leader” than “Religious Leader.” Religious Leaders 1. Reverend John Jasper, 1812‐1901 Richmond Nominated by Benjamin Ross, Historian, Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church Religious leader Rev. Jasper was born into slavery on July 4, 1812 in Fluvanna County, Virginia, to Philip and Tina Jasper one of twenty‐four children. Philip was a Baptist preacher while Tina was a slave of a Mr. Peachy. Jasper was hired out to various people and when Mr. Peachy's mistress died, he was given to her son, John Blair Peachy, a lawyer who moved to Louisiana. Jasper's time in Louisiana was short, as his new master soon died, and he returned to Richmond, Virginia. Jasper experienced a personal conversion to Christianity in Capital Square in 1839. Jasper convinced a fellow slave to teach him to read and write, and began studying to become a Baptist minister. For more than two decades, Rev. Jasper traveled throughout Virginia, often preaching at funeral services for fellow slaves. He often preached at Third Baptist Church in Petersburg, Virginia. He also preached to Confederate Soldiers during the American Civil War (1861‐1865). After his own emancipation following the American Civil War, Rev.